The Most Controversial Films in Cannes History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Throughout its illustrious, seven-decade history, the Cannes Film Festival has never been afraid to embrace a little controversy. Sometimes it’s a film’s content, like when Gaspar Noé’s relentlessly violent thriller Irreversible caused multiple festivalgoers to faint in 2002. Other times the quality—or lack thereof—can become the scandal, like when film critic Roger Ebert declared The Brown Bunny “the worst film in the history of Cannes” and traded insults with its director, Vincent Gallo.

Even the festival’s well-reviewed films can’t fully escape Cannes-induced scrutiny. A director winning the festival’s top honor—the highly coveted Palme d’Or—doesn’t mean their acceptance speech will be audible over a chorus of boos. It’s a longstanding tradition for Cannes audiences to vocalize their thoughts on a film as the credits roll, typically in the form of a standing ovation or prolonged jeering.

“There is something all very heightened there,” Sofia Coppola—whose Marie Antoinette was booed at its Cannes premiere—once told the Associated Press. “There’re definitely a lot of opinions and provocations. That’s part of it.”

In honor of the festival returning to an in-person gathering this month, Vogue took a look back at some of the most notorious films in Cannes history that stirred up drama along the Croisette.

la dolce vita

La Dolce Vita (1960)

Tracing the decadent exploits of a tabloid journalist drifting through Rome, Federico Fellini’s masterful satire arrived at Cannes with controversy already in tow. La Dolce Vita had already bowed in the director’s native Italy, where its immoral, pleasure-seeking ethos turned it into a cultural sensation—and earned the scorn of the Catholic Church. The Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano condemned the film in an article entitled “La Schifosa Vita” (“The Disgusting Life”). The fundamentalist Catholic right took particular offense to the film’s opening sequence, where a helicopter carries a statue of Christ over Rome to the awe and amusement of onlookers below.

All the hullabaloo only turned the film into a bigger talking point by the time it bowed at Cannes to enthusiastic reviews. Fellini took home the festival’s coveted Palme d’Or, with La Dolce Vita going on to become a box office hit in America and earn four Oscar nominations.

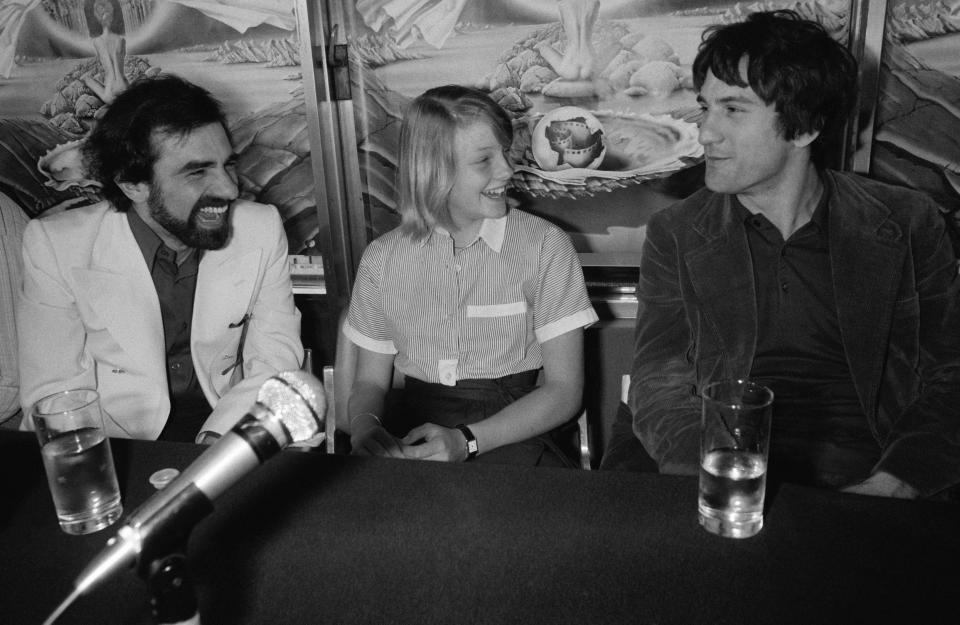

taxi driver

Taxi Driver (1976)

A year after a bomb was discovered inside the Palais des Festivals—a failed attempt by a terrorist group—Martin Scorsese’s paranoia-fueled masterpiece premiered to an uneasy Cannes audience in 1976. Following the mental deterioration of a wounded Vietnam vet played by Robert De Niro, Taxi Driver became the target of jury president Tennessee Williams, who openly criticized the amount of bloodshed in that year’s festival slate. “Watching violence on the screen is a brutalizing experience for the spectator,” Williams told reporters. “Films should not take a voluptuous pleasure in lingering on terrible cruelties as though one were at a Roman circus.”

Yet the Cannes jury couldn’t deny the film’s artistic merits, ultimately awarding Taxi Driver the Palme d’Or. “Half the audience was on its feet cheering,” recalls producer Michael Phillips. “The other half was booing.” Not that Scorsese was there to face his critics: After catching wind of just how much Williams hated Taxi Driver, the director skipped the awards ceremony and flew back to the U.S.

Cannes Film Festival

Do the Right Thing (1989)

If you were to bet money at Cannes in 1989, Spike Lee was the odds-on favorite to win the Palme d’Or. Do the Right Thing pierced the stuffy festival atmosphere, earning critical raves for its depiction of escalating racial unrest in a Brooklyn community. “It’s a great film, a great film,” Roger Ebert declared after a screening. “If this doesn’t win the grand prize, I’m not coming back next year.”

When the Palme went to Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape instead, Lee was dumbfounded. Jury president Wim Wenders purportedly found Do the Right Thing’s lead character “unheroic” and questioned his decision to throw a trash can through a storefront window at the end of the film. “Wim Wenders had better watch out cause I’m waiting for his ass,” Lee said afterward. “Somewhere deep in my closet I have a Louisville Slugger bat with Wenders’s name on it.” Lee later said that while “it was stupid” to threaten Wenders, Do the Right Thing deserved proper recognition.

THE FILM CREW FROM 'PULP FICTION' IN CANNES

Pulp Fiction (1994)

No one was more surprised when Pulp Fiction won the Palme d’Or than Quentin Tarantino. “I never expect to win anything when a jury has to decide because I don’t make the kinds of movies that bring people together,” the filmmaker told the booing crowd. “I make the kinds of movies that split people apart.”

The sprawling crime epic was the most discussed film at Cannes, though, as the Los Angeles Times noted, “not necessarily the most admired.” Krzysztof Kieślowski’s romantic mystery Three Colors: Red was a much more traditional critical darling primed for the Palme. After Pulp Fiction was announced the winner, a woman in the balcony even screamed, “Kieślowski! Kieślowski!” as Tarantino walked to the stage. Ever the peacekeeper, Tarantino reportedly responded by giving the “jeering protester the finger as he accepted the prize from Kathleen Turner.”

On the set of Crash

Crash (1996)

“Cannes Finally Gets a Noisy Controversy,” The New York Times declared of the polarizing reception to Crash. Following an underground subculture of individuals who get turned on by car accidents, David Cronenberg’s kinky exploration of the line between sex and violence (based on the J.G. Ballard novel) was greeted with a stormy mix of boos and jeers. The American press expressed its fair share of disgust, while the British tabloids were apoplectic with rage. The Evening Standard opined that Crash contained “some of the most perverted acts and theories of sexual deviance...ever seen propagated in mainline cinema.” The Daily Mail described it as “the point at which a liberal society must draw the line.”

Jury president Francis Ford Coppola allegedly despised the film and strongly opposed its contention for the Palme d’Or. While Crash ended up losing to Secrets & Lies, the jury created a Special Jury Award to honor Cronenberg. “I think it was the jury’s attempt to get around the Coppola negativity, because they had the power to create their own award without the president’s approval,” the filmmaker later said. “But it was Coppola who was certainly against it.”

Cannes Danny Cunningham holds Pigeons

24 Hour Party People (2001)

Bawdy and appropriately outrageous, 24 Hour Party People depicts the glory days of the Manchester music scene in the late ’70s. Michael Winterbottom’s comedy gleefully dramatizes the exploits of groups like Joy Division and Happy Mondays, whose lead singer infamously poisoned more than 3,000 pigeons with bread dipped in a variety of stimulants (rat poison, crack cocaine, ecstasy, etc.). As depicted in the film’s most memorable sequence, the birds plummeted from a Manchester rooftop en masse and wreaked havoc below.

In a case of life imitating art imitating life, the young actors portraying Happy Mondays caused a scene at Cannes with a publicity stunt gone awry. Armed with a batch of dead pigeons stuffed with real feathers and fake blood, the actors started attacking each other in the water near the posh Majestic Beach restaurant. The management had agreed to the stunt but stepped in when the actors started pelting birds at their customers. Joel and Ethan Coen were dining at the Majestic and reportedly were “highly amused” by the stunt. Security guards eventually threatened the rowdy actors with mace and quickly ejected them.

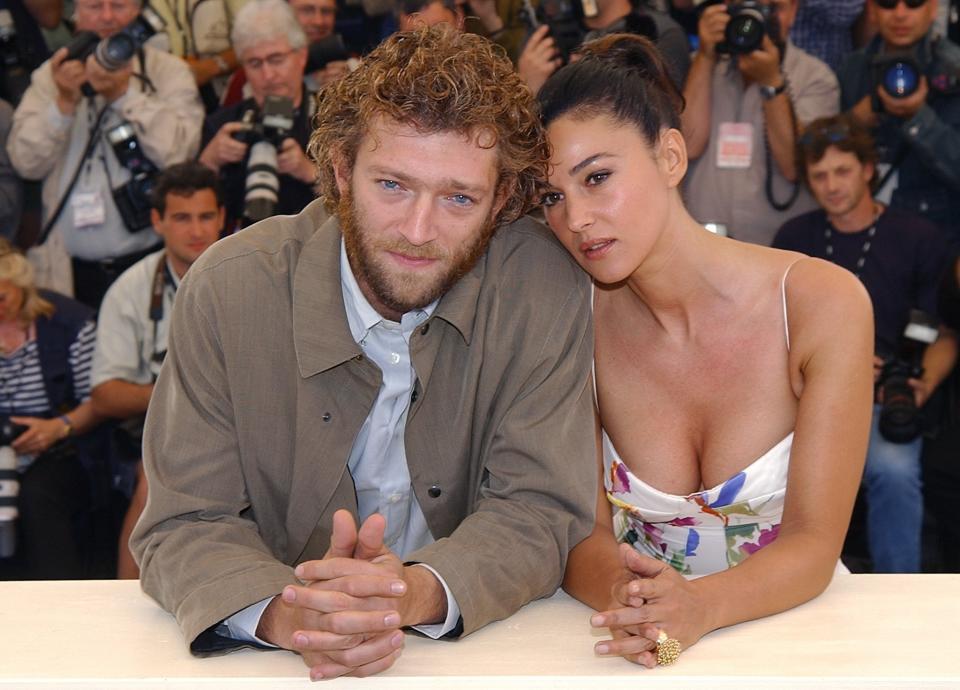

Italian actress Monica Bellucci and French actor V

Irreversible (2002)

Gaspar Noé’s wildly controversial—and widely detested—thriller remains the most notorious premiere in Cannes history. It’s estimated that at least 200 audience members walked out of a screening, with 20 others reportedly needing medical assistance after fainting. “In 25 years in my job, I’ve never seen this at the Cannes festival,” a fire-brigade spokesman told the BBC. “The scenes in this film are unbearable, even for us professionals.”

Starring then couple Vincent Cassel and Monica Belluci, the film chronicles one man’s search for revenge against the man who raped his girlfriend. Told in a reverse, nonlinear structure, Irreversible’s stomach-churning centerpiece is the nine-minute rape of Belluci’s character, the only scene in the film where the camera remains in a fixed position. Even two decades later, its unrelenting brutality remains nearly unwatchable.

Like most of Noé’s output, Irreversible has its fair share of defenders. More viewers fell in line with the opinion of Le Monde, whose critic wrote that “the film’s gratuitous violence is proportionate to its intellectual laziness.”

2003 Cannes Film Festival - "Brown Bunny" Premiere

The Brown Bunny (2003)

The Brown Bunny was the most talked-about film at Cannes in 2003 but not for its artistic merit. A media storm erupted when word got out that the melodrama climaxed with Chloë Sevigny performing an unsimulated sex act on her costar—and then boyfriend—Vincent Gallo. A widely spread rumor falsely claimed that Sevigny’s agents at WME had dropped her for doing irreparable damage to her career. (They still rep Sevigny, who seems to be doing just fine.)

The sex scene ended up being one of the less damning criticisms of the film. The New York Times reported that the first press screening “was remarkable for the unrestrained hostility of the audience.” Following a motorcycle racer haunted by memories of a former lover, The Brown Bunny was widely derided as a lethargic vanity project from Gallo (who also produced, wrote, directed, shot, and edited the film). In response to Roger Ebert’s pointed criticisms, Gallo told Page Six that he’d placed a hex on Ebert to give him colon cancer. “I had a colonoscopy once, and they let me watch it on TV,” Ebert wrote. “It was more entertaining than The Brown Bunny.”

Award Winners Photocall

Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004)

Throughout its history, the Cannes Film Festival has been openly indifferent to documentaries. When Fahrenheit 9/11 took the festival by storm in 2004, it was only the third nonfiction film allowed to compete in more than 50 years. A searing critique of the Bush administration, Michael Moore’s documentary premiered to a 20-minute standing ovation, one of the longest in festival history, and later won the Palme d’Or.

“What have you done?” the filmmaker quipped to jury president Quentin Tarantino as he accepted the prize. “You just did this to mess with me, didn’t you?”

The crowd at an international film festival may have responded warmly to a film attacking American politics, but Fahrenheit 9/11 spent the rest of the year mired by intense scrutiny. Released several months ahead of the 2004 election, Moore stated outright that he “hoped to see Mr. Bush removed from the White House.” The film inspired heated debates over propaganda versus persuasion on the way to becoming the highest-grossing documentary of all time.

59th Cannes Film Festival :Photo call of "Marie Antoinette" in Cannes, France on May 24, 2006-

Marie Antoinette (2006)

An American director’s take on the story of Marie Antoinette was destined to polarize European audiences. And coming off the Oscar-winning success of Lost in Translation, Sofia Coppola had even more eyes trained on her big-budget biopic. “We always knew that the French are protective of their history, and that’s one of the challenges,” the filmmaker said. “But I wanted to show it in France first.”

Depicting the life and times of the doomed French queen, Marie Antoinette was greeted with a resounding non at Cannes. The New York Times reported that “lusty boos and smatterings of applause” filled the air after a screening. Many critics singled out the film’s emphasis on sumptuous visuals over historical accuracy, but Coppola took the criticism in stride. “I think it’s better to get a reaction than a mediocre response,” she said. And like the majority of films on this list, critical esteem for Marie Antoinette has only grown in the years since.

2009 Cannes Film Festival - "Antichrist" Photocall

Antichrist (2009)

Lars von Trier is no stranger to controversy. The Danish filmmaker has fielded criticisms of misogyny, workplace abuse, and general assholery throughout his career. Bjork vowed to never act again after working with Von Trier on Dancer in the Dark. Nicole Kidman famously went through the wringer on the set of Dogville, with her costar Paul Bettany referring to the experience as “eight enormously long weeks in the most depressing place I have ever been to in my life.”

Von Trier took audiences to an even more depressing place with Antichrist in 2009. It opens with the slow-motion death of a child falling from an upstairs window, and things only get more gruesome from there. Having been in the shower having sex during the incident, the child’s unnamed parents retreat to a cabin in the woods, where their grief and guilt begin to drive them mad. In a telling sign of the film’s polarized Cannes reception, Charlotte Gainsbourg won best actress while Von Trier earned a special anti-award from the jury, which declared Antichrist “the most misogynist movie from the self-proclaimed biggest director in the world.”

Palme d'Or Winners Photocall- 64th Annual Cannes Film Festival

Melancholia (2011)

Following the vitriolic response to Antichrist, things were looking iffy for Von Trier going into Cannes in 2011. But Melancholia, which depicts a bride on her wedding night trying to navigate the fog of clinical depression—while a rogue planet hurtles towards earth—earned him and his leading lady, Kirsten Dunst, the best reviews of their respective careers. Better known for bubbly comedic turns in hits like Bring It On, Dunst was touted as an Oscar frontrunner.

Cut to: “Lars von Trier Admits to Being a Nazi, Understanding Hitler.”

Von Trier ended up sinking the film before Cannes had even concluded. During a news conference with Dunst, the Danish director went on a tangent stemming from a question about his recently discovered German heritage. “What can I say? I understand Hitler,” he said. “I think he did some wrong things, yes, absolutely, but I can see him sitting in his bunker in the end.”

At one point, a mortified Dunst tries to cajole Von Trier away from digging a bigger hole. “But, come on, I am not for the Second World War, and I am not against Jews,” he continued. “How can I get out of this sentence...okay, I’m a Nazi!”

The festival board declared Von Trier persona non grata immediately, temporarily banning him from the festival. Dunst won the best-actress prize while The Tree of Life scooped up the Palme d’Or, a largely unexpected win that many attributed to Von Trier’s eleventh-hour controversy. “I got carried away,” Von Trier told The New York Times. “I feel this obligation, which is completely stupid and very unprofessional, to kind of entertain the crowd a little bit.”

France - 66th Cannes International Film Festival Closing Ceremony

Blue Is the Warmest Color (2013)

The romantic drama treks the highs and lows of a whirlwind relationship between a free-spirited painter (Léa Seydoux) and a French teenager (Adèle Exarchopoulos). Directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, Blue Is the Warmest Color bowed at Cannes to rave reviews and a slew of audience walkouts, most notably during a 10-minute sex scene. The intimate scenes between Seydoux and Exarchopoulos drew as much praise for their intense eroticism as they did ire for the perceived male gaze of their filmmaking. “As the camera hovers over [Adèle’s] open mouth and splayed body, the movie feels far more about Mr. Kechiche’s desires than anything else,” The New York Times wrote.

In an unprecedented move, the Cannes jury—stunned by Seydoux and Exarchopoulos’s performances—split the Palme d’Or between the two actresses and their director. The film was poised to become the indie darling of awards season. Months later, while promoting the film during the Telluride Film Festival, the two actresses spoke out about the “horrible” conditions that Kechiche put them through while filming.

“Once we were on the shoot, I realized that he really wanted us to give him everything,” said Exarchopoulos. “Most people don’t even dare to ask the things that he did.” Seydoux claimed that filming the sex scenes was humiliating and made her feel “like a prostitute.” Both actresses said they would never work with Kechiche again, who denied claims of mistreatment, calling Seydoux’s remarks “slanderous” and referring to her as an “arrogant, spoiled child.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue