More Black Teachers Mean More Equitable Education

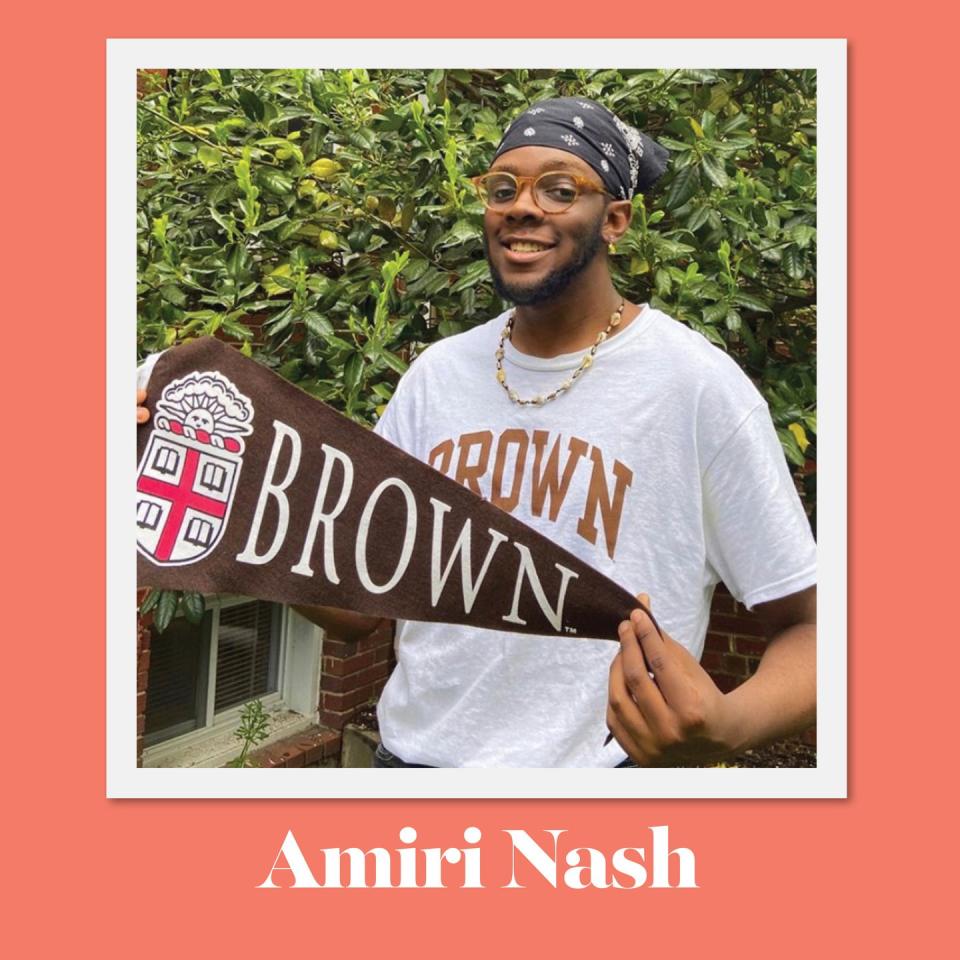

Amiri Nash keeps a picture of his 11th grade English teacher, Tiffany Jackson, on the wall of his college dorm room. He considers her family and one of his greatest inspirations.

“I think the thing that makes Ms. Jackson so different from other teachers is the way that she applies the world to lessons,” says Nash, now a sophomore at Brown University in Providence, RI. “She doesn’t remove life from the work that she does.”

One of Nash’s favorite lessons from Jackson’s class was her use of Beyoncé’s Lemonade to teach the basics of rhetorical analysis. And he says that when he’s having a tough day in his college English classes, he thinks back to Jackson’s teaching style to stay motivated.

“I think that seeing how much Ms. Jackson owned being an English teacher and owned the English language gives me the courage and the hope and the possibility to know that I’m doing the right thing,” Nash says.

Nash met Jackson when he was a student at the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, DC. Despite attending the school to study classical piano, Nash recently declared English as his major at Brown.

“I would never have done that if it wasn’t for Ms. Jackson’s class,” Nash says. “I wouldn’t have seen how nonconventional and exciting English could be.”

Black educators show students what’s possible

While at Brown, Nash has been making headlines – literally. He founded and runs The Black Star Journal, the school’s new publication for Black students. Nash credits the critical-thinking skills he learned in Jackson's class with helping him to launch the newspaper. “Ms. Jackson is a very grounding person and I think that taking her class was a very transformative experience because it gave me the tools to think beyond what I can see just in front of me,” he says.

Passionate about social justice, Nash is kicking around the idea of attending law school. He's also passionate about pursuing journalism. Jackson helped plant that seed too. It was through her class that Nash was connected with Press Pass Mentors, a program that allowed him to shadow a reporter at The Washington Post and learn more about that world.

But Jackson is reluctant to take credit for the accomplishments of Nash and other high-achieving students.

“Amiri was a genius when he got to me,” Jackson says. “And that is something that I really try to instill in the kids, that the genius is innate. It’s already there.”

Instead, she says it’s her job to help bring out that genius, partly by exposing students to opportunities like Press Pass Mentors.

“Teachers are important because a teacher is a gatekeeper,” she says.

“What if I was someone who didn’t believe that all of them have genius in them?”

This is one of the many reasons she believes it’s important for Black students to have Black educators. Currently, however, only 7% of K-12 teachers are Black. After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case ended segregation in schools, tens of thousands of Black teachers lost their jobs, leaving a gap in our educational system that has never been closed. But teachers like Jackson are determined to build a bridge.

Jackson, who has worked in education for 15 years, has taught solely in her hometown of Washington, D.C. because it’s important to her to give back to the community in which she grew up. She can’t remember a time when she didn’t want to be a teacher, she says, a calling inspired by her love of school and her vivid memories of her own favorite teacher, Ms. Gloria P. Walton.

“School was a production for her,” Jackson says. “I fell in love with the idea that learning is something we can see and feel and hear.” When asked the number one lesson she hopes her students learn from her, Jackson quickly answers, “That they have tools to think their way through any situation.”

Teachers need support to tell the truth

Currently, Jackson teaches at the KIPP DC College Preparatory. That means her curriculum could be directly impacted by legislation seeking to ban Critical Race Theory from schools.

“Y’all going to have to get over me telling the kids this whole truth—the unvarnished, unpolished, unapologetic truth—because they need to know it,” she says. “Ignorance is not bliss; it's detrimental to humanity. There’s no Amiri talking about going to law school or starting a paper without us talking about race in a plain and thoughtful way in high school.” To recruit and retain more Black educators in K-12 schools, Jackson believes that, first and foremost, teachers need what any employee needs.

“On the surface it’s the things we all need,” Jackson says. “We need to be getting paid well. We cannot continue to survive in a world where all these costs are going up around us and teachers are working massive amounts of hours and not getting paid for what they put in.”

But just as important as salary is how teachers are treated on the job.

“We shouldn’t have to deal with the badgering that we do on all types of levels,” Jackson says of the harsh criticism and disparaging remarks many teachers often endure, adding that it doesn’t just come from students. “We get it from parents, we get it from city officials, we get it from administrators and policy makers and congressmen.”

Schools also need to get serious about anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion. “Right now, people are playing at it,” Jackson says. “They’re using the language, but they don’t mean it.” She stresses that schools must create an environment in which Black educators and students feel safe.

“How am I supposed to protect Black boys and girls in a building where my voice is silenced?” Jackson asks. “Administrators may be talking about my hair and my clothes, so how am I supposed to make sure the kids can do what they need to do and can explore themselves?”

Jackson notes that dress codes for both students and adults typically are biased against women, girls, and Black people.

“Styles of clothes and hair that are natural and culturally relevant to us are often the ones deemed ‘unprofessional’ or ‘inappropriate,’” Jackson says. While she says she hasn’t directly been reprimanded, she’s seen a fellow teacher fired for wearing a short skirt, and another tasked with policing the dress of other adults.

“I always worry about what I have on and what style my hair is in when getting ready for school each day,” Jackson says.

Taking her lessons into the world

Outside the classroom, Jackson also serves as the lead consultant for Black Girls Teach, an organization that seeks to empower and connect Black women educators by offering community and networking opportunities as well as professional and personal development, advocacy and career advancement initiatives.

“We offer them a chance to commune and grow and learn in spaces made just for them,” Jackson says of Black Girls Teach. While Jackson believes it’s important for Black students like Amiri to have Black educators, she thinks it’s equally important for non-Black students to be exposed to a diverse group of teachers. She remembers one of her non-Black students remarking to her how having Black teachers and Black friends helped him better understand the power of listening.

“He said, ‘I don’t always have the answer. I need to listen,’” Jackson recalls. “That changed how he showed up in the world.”

For educators like Jackson, teaching isn’t a job; it’s their life’s work.

“Teaching is a craft that must be honored and protected,” Jackson says. “Black educators are critical to the profession, and when Black educators are teachers, administrators, talent managers, superintendents and policy makers, all our kids will thrive.”

Tiffany Jackson

What gives you hope about the future?

Amiri and his classmates. My kids are making art, dropping mixtapes and starting papers and doing TED Talks and making clothes, living sustainably and they’re empathetic and they’re thoughtful and they’re considerate of each other and they understand the inner workings of humanity and they’re funny. I get to live in their world, and I just can’t wait to see what it’s going to be. They’re my hope.

What’s in store for your future?

I’m going to hang on to this classroom as long as I can. I have two sons–one is 7 and one is 5–I’m going to raise. I’m going to continue to work on Black Girls Teach, making sure we do the work to retain and hire and bring quality Black thinkers and creators into the classroom for our kids.

Why is thinking about the future important?

Liberation starts with dreams. Harriet Tubman had that dream to get off of that plantation. You have to dream about it. You have to give yourself the space to imagine what it could be. We don’t get a future if we don’t think about it now–or we don’t get the one that we want. We get somebody else’s.

Amiri Nash

What gives you hope about the future?

As a Black person, what gives me hope about the future is being able to reflect critically about the past and see how far we’ve been able to come and really build off of the strength of the people that came before me. If they did that and they only had this, just imagine how much I can do and just imagine how much the people after me can do.

What’s in store for your future?

When I think of my future, I think of being creative and leaving the world a better place than it was when I came into it. So, I definitely think creativity is in my future, but I also think that healing for myself and other people is in my future.

Why is thinking about the future important?

People are really blessed to be alive and have the chance to do something with the future. We have a chance to really make that future something that works better for all of us.

This story was created as part of Future Rising in partnership with Lexus. Future Rising is a series running across Hearst Magazines to celebrate the profound impact of Black culture on American life, and to spotlight some of the most dynamic voices of our time. Go to oprahdaily.com/futurerising for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like