How the Moon Once Turned Inside Out

There are a lot of fairytales about the Moon, and they’re all pretty far-fetched. There’s a man up there, possibly marooned by god as a punishment for gathering sticks on the Sabbath. It’s made of cheese; it’s hollow; it’s a spacecraft. Humans never set foot on it.

And so on. The latest lunar theory sounds as wacky as any other — but according to the planetary scientists who developed it, it’s more than plausible.

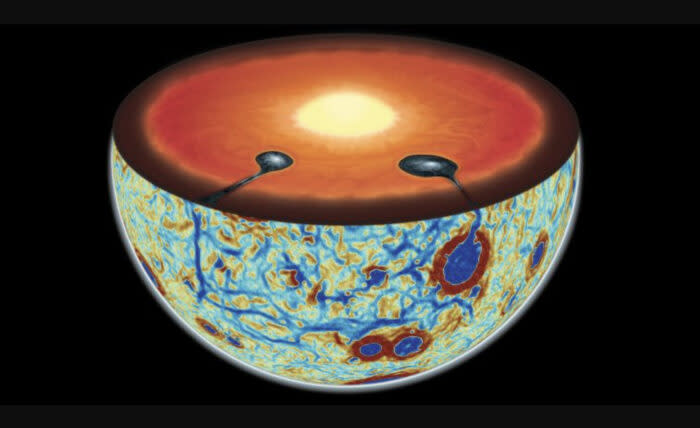

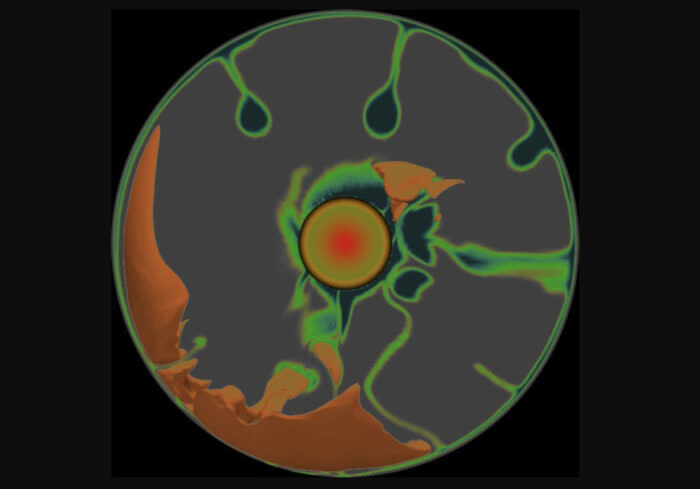

The Moon once turned inside out, according to a model from Weigang Liang and Adrien Broquet of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Sciences Lab. It happened when a giant primordial ocean of magma crystallized and sank below the surface, trading places with the upwelling mantle.

Mantle flip-flop

It’s called lunar mantle overturn, and it’s been under study for decades. Researchers first noticed discrepancies on the lunar surface: deposits of certain metals and dense volcanic rocks in unexpected places.

Until now, Liang and Broquet pointed out, nobody has produced physical evidence that links the surface conditions to the lunar flip-flop.

“Despite abundant geochemical evidence, there has been a lack of physical evidence on the nature of the overturn,” their study, published in Nature Geoscience, reads.

The Moon’s near side today is a hardened soup of metallic and volcanic deposits of various densities. There’s the KREEP Terrane, which contains potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus. These overlap with the lunar maria — the visible dark blotches on the satellite.

Early astronomers mistook these for actual seas. (Mare is Latin for “sea.”) They’re darker because of their iron content, thanks to the presence of a mineral called ilmenite, a titanium-iron mix.

The subterranean materials — olivine, orthopyroxene and clinopyroxene — are less dense. Why didn’t the ilmenite just sink into the mantle and become bedrock for these lighter-weight materials?

A ‘critical record’ preserved

Liang and Broquet suggested that dense ilmenite formed a layer between the crust and mantle as the liquid magma ocean of the young Moon cooled and crystallized, according to ScienceAlert.

The ilmenite may have resurfaced later through reheating. This and a giant impact could have affected the Moon’s gravity and relayered its composition so that the mantle sat on top.

Liang and Broquet’s models of lunar mantle overturn indicated gravitational anomalies. They used readings from two NASA spacecraft that have extensively mapped the lunar surface to compare the models with reality.

The models matched what these spacecraft observed. It confirms the lunar mantle’s overturn and dates it to at least 4.22 billion years ago.

“The lunar gravity field preserves a critical record of the overturn of the lunar mantle that has been widely postulated to be one of the defining events in early lunar history, but the details have until now remained unknown,” the researchers concluded.

Even the Earth has its rare spots where the mantle — the thick middle layer below the thin but familiar crust — has percolated to the surface, such as on Macquarie Island in Tasmania and the Tablelands in Canada’s Gros Morne National Park. However, these areas are small compared to the mantle’s significant presence on the Moon due to that ancient flip-flop.

The post How the Moon Once Turned Inside Out appeared first on Explorersweb.