Moody Harney A.K.A. The Real Mothershucker Is Bringing Oysters Back To The People

On a busy stretch of Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, Moody Harney sets up his oyster cart on a sunny July afternoon. Harney’s business, The Real Mothershuckers, harkens back to a time when oysters were an affordable and accessible street food and an integral part of many Black neighborhoods.

Oysters today are often seen on high-end restaurant menus and expensive seafood towers, but they come from humble beginnings. After years of shucking oysters at fine-dining establishments, Harney did a deep dive into the mollusk's history and was inspired to share the story with his community.

History

In North America, oysters were an integral source of protein for indigenous communities along the East Coast, and later for colonial settlers and enslaved Africans. Harney explained it was also one of the building blocks of the early economy. "Trapping fur was how we got clothes, whaling was how we lit up the city, and oystering was how we got nutrition," he said.

"It was one of only a few industries where Black people had the opportunity to gain individual wealth and have leadership positions at the time," he said. "They were captaining whale and oyster ships, and it was extremely common for them to be working on them. It's really labor-intensive work, grunt work. They'd harvest at least a ton per day. But coming back and processing oysters was where a black man could make money."

Black settlers in the northern United States not only embraced oysters as cuisine, but also greatly expanded the industry.

"The Black community of Sandy Ground was actually one of the first actual towns in Staten Island, period. It was founded as an oystering community and it was in the sweet spot in the New York Harbor where they could sell their products to the surrounding areas," Harney said.

"The founding of communities on Staten Island, the Hamptons, Sag Harbor, all of the Chesapeake Bay, and Connecticut were the beginning of the American oyster trade. These places were being carved out by free native Americans, African Americans, and Irish immigrants," Harney added. "The most well-known oyster, the Blue Point, was first sold from these colonies in New York."

These colonies grew the oyster trade while Black men sold oysters in basement cellars and from street carts. In the early 19th century, the majority of registered oystermen in New York were of African descent. “They had to earn their respective freedoms,” said Harney, “and Black people were extremely successful in the oystering industry.”

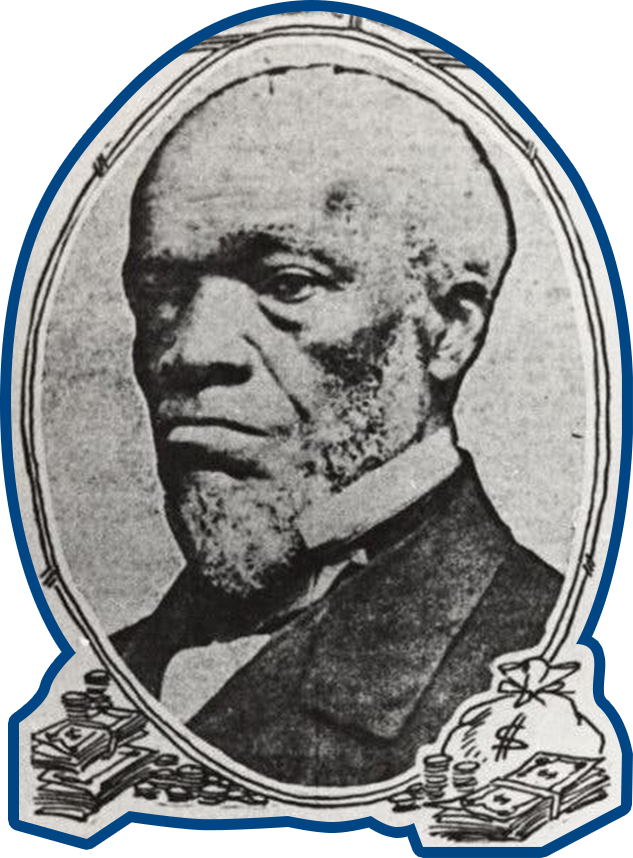

Enter: Thomas Downing

One of these men, Thomas Downing, was the primary inspiration for Harney to open The Real Mothershuckers. Downing first began oystering after fighting in the War of 1812. Initially catching his own oysters and selling his daily haul, he later opened up the Thomas Downing Oyster House in New York City.

Unlike the low-brow oyster dive bars and carts that were spread throughout Manhattan, Downing’s establishment was upscale and elaborately decorated. The Thomas Downing Oyster House became an exclusive spot that attracted elite guests while also serving as a station in the Underground Railroad. Downing even shipped oysters to Queen Victoria, helping to usher in a new era that transformed oysters into a luxury. "Downing and the pioneers that came after him made it fancy when it was a common food," Harney said.

While the oyster boom greatly increased the value and demand for the product, it also boxed out many people—predominantly low-income people of color.

Many Black-owned oyster farms were parceled off and sold to real estate developers; the local oyster supply was contaminated by toxic sewage; and the subsequent increase in the cost of oysters made the food inaccessible to the communities that loved to eat them. “Thomas Downing was game-changing," Harney said. "He's the reason why oysters became fine dining in the first place. But his impact, along with the disappearance of the oysters from our waters, turned it into an elitist food.

The Real Mothershuckers

This is exactly why Harney is shucking oysters today: to bring them back to his community after decades of exclusion. He sets up his cart outside local restaurants like BK Lobster and engages with his Brooklyn neighbors. “The majority of people in the U.S. are landlocked and haven’t had an oyster, period, and if they can it’s from wherever they can afford. What I want to do is encourage everyone to try oysters and learn about different regions, textures, flavors, and ways to eat them."

"There’s no reason that in NYC, which has historically been the oyster capital of the world, people shouldn’t have access to oysters and oyster culture," Harney said.

Unlike the "mushy" and "swampy" oysters you can sometimes find at dollar happy hour spots, Harney sources his oysters from vendors and farmers he trusts. Each of his oysters cost three to four dollars apiece, but the price reflects the quality of his product and the value of the farmers' labor.

"The price of oysters shouldn’t change, because it’s already cheap for what these farmers do. They do it by themselves year round in the middle of the ocean, in the middle of the ice and snow. And they bring it back to people who don’t even understand what they’re eating," he continues, "With the proper education, people will realize that oysters are worth the money they spend to eat them."

Harney's mission isn't just to serve great oysters and foster community while doing it; he's also dedicated to improving the industry's sustainability.

Oyster shells are essential for water filtration. They build environmental infrastructure and restore habitats. Harney explained that Native American communities used to pile discarded oyster shells along coastlines for centuries. European settlers mistakenly referred to these mounds as "køkkenmøddinger," which translates to "kitchen waste." However, these shell piles weren't trash, but rather an effective way to prevent floods.

Harney has partnered with The Billion Oyster Project to donate used shells and use these indigenous techniques to help rebuild the New York Harbor. While New Yorkers may never again be able to rake through city waters for wild oysters, Harney said their role is more important than just being delicious. "I always say a little prayer with every oyster I shuck: 'God bless you in death as you bless us in life.'"

Harney has been featured in the Netflix series High on the Hog and several media campaigns, but his vision for The Real Mothershuckers isn't over yet. He continues to expand his locations and spread the oyster gospel to whomever is willing to listen. "I'm always going to keep using carts. The main advantage is that we can put oysters in all sorts of places with ease and build community spaces. In that, it also creates employment opportunities and food justice for New York City-based youth," he said.

As Harney cracks open half a dozen East Coast oysters, a woman walking down Flatbush Avenue stops to ask what he’s doing. Without skipping a beat, Harney hands her a fresh oyster and explains the difference between each variety he sells. She’s never had an oyster before, but his contagious passion convinces her to try one.

After tasting the unfamiliar, algae-covered mollusk, the woman is a self-proclaimed convert. She immediately orders six more for herself, and then heads home to grab more cash for another half dozen.

"What's a real mothershucker?" she asks. Harney responds: "It's me. I'm the real mothershucker."

You Might Also Like