Will MoMA’s New Commissions Make the Museum Modern Again?

On a Wednesday afternoon in the dog days of summer, a trickle of tourists strays hopefully through the Museum of Modern Art’s staff entrance, only to be gently shown a reopening OCTOBER 21 sign, followed by the door. For a closed museum, however, the place is exceptionally busy. Carts, dollies, buckets, trestle tables, and concertina platforms are rolled around the open floors in a complex yet orderly choreography. It’s as if the legacy of Philip Johnson’s modernist strictures—Johnson served in the museum’s architecture department in the ’30s and expanded its original 1939 structure in 1964—is conferring its own set of minimalist manners on the building’s current occupants.

I am handed a rather chic white hard hat bearing MoMA’s distinctive black logo and escorted on a work-in-progress tour by a posse of female staffers. First impression: The interior, which has swallowed up the former home of its neighbor, the American Folk Art Museum, in a westward march along 53rd Street, feels newly rangy. The MoMA reboot includes 30% more gallery space and a greater number of exhibits accessible to the public before they even pay admission.

“Acupuncture” is how the museum’s director, Glenn D. Lowry, describes the expansion, bringing new life, air, and energy into a building that could seem weighed down by its own importance. As Elizabeth Diller, of the architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, describes the institution whose renovation the company took on, “Despite the fact that the public flocks to its doors, MoMA feels a bit aloof, and not spontaneous enough.”

“Audiences want experiences now,” Lowry agrees. “They don’t just want to look at art; they want to feel engaged with it and surrounded by it.”

New York museums, like those of other major cities, are involved not just in the race to stay ahead architecturally but also to adapt to the changing priorities of artists and accommodate dramatic shifts in culture. If MoMA’s last expansion, by the Japanese architect Yoshio Taniguchi in 2004, drew criticism for its hefty price tag—part of a $858 million capital campaign—and corporate-looking design, its current incarnation, at $400 million, sets out to break down authoritarian assumptions about what art we should be presented with, and how. The rehang/reopening will include shows dedicated to Latin American art and to the work of 93-year-old African American artist Betye Saar, evidence of a stated commitment to greater diversity and mixing of genres. Two new galleries, accessible from the street and free to the public, have been added—one will present an exhibition by the terrific young painter Michael Armitage—along with a dedicated performance studio on the fourth floor.

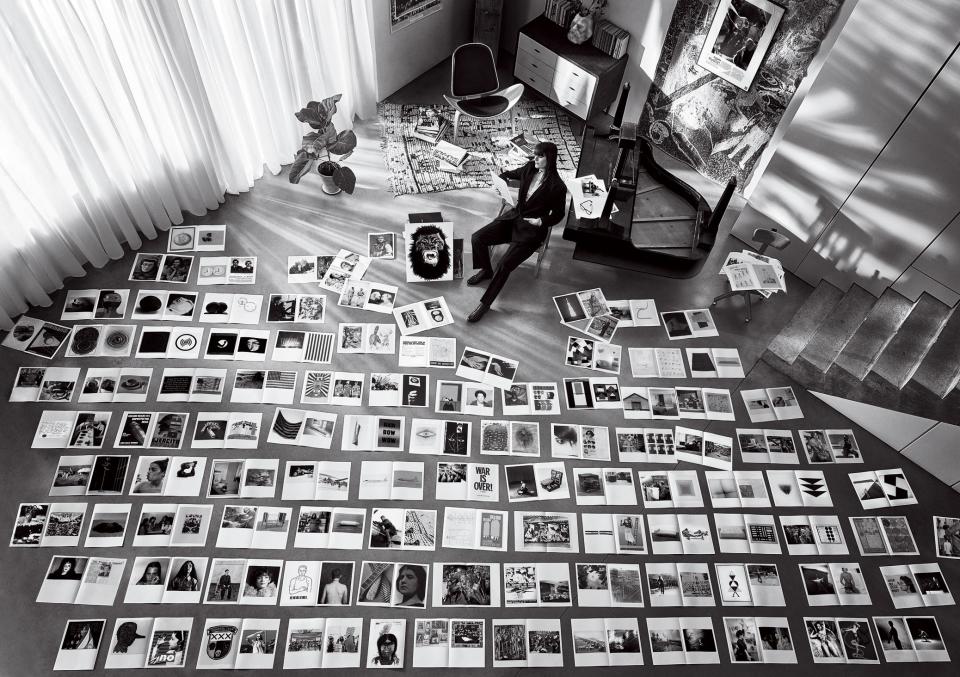

Bringing this rethink to life, a series of artist commissions—sited mainly outside the galleries and many by women—is being installed. Yasmil Raymond is the vivacious curator overseeing these projects (along with her colleague Tara Keny). Raymond leads us to the education building, where Andy Warhol’s famous pink-and-yellow cow wallpaper is being peeled off to make way for a piece by another artist of Slavic origin, Goshka Macuga. Macuga uses photography-based tapestry to present layered investigations into political movements and their influence on art history. Here, she reimagines a famous photograph from 1954 that depicts the French writer and culture minister André Malraux in his home, with layouts from his canonical art book, Museum Without Walls.

“It’s an iconic image of a male curator of the 20th century,” Macuga says. “A white bourgeois man smoking a cigarette in his house leaning against a piano.” In Macuga’s version of the photograph, she takes up position in a similar room, with her own selection of images arranged on the floor. It’s one that unearths many more women—from artists Meret Oppenheim and Vija Celmins to donors such as Elizabeth Bliss Parkinson Cobb, who helped sustain the museum for decades. At 50 by 36 feet, it is Macuga’s most ambitious project yet. “It’s a big gesture for MoMA to invite living artists to make commissions that will remain for up to 10 years,” she says. “I wanted it to be like an exhibition within an exhibition.”

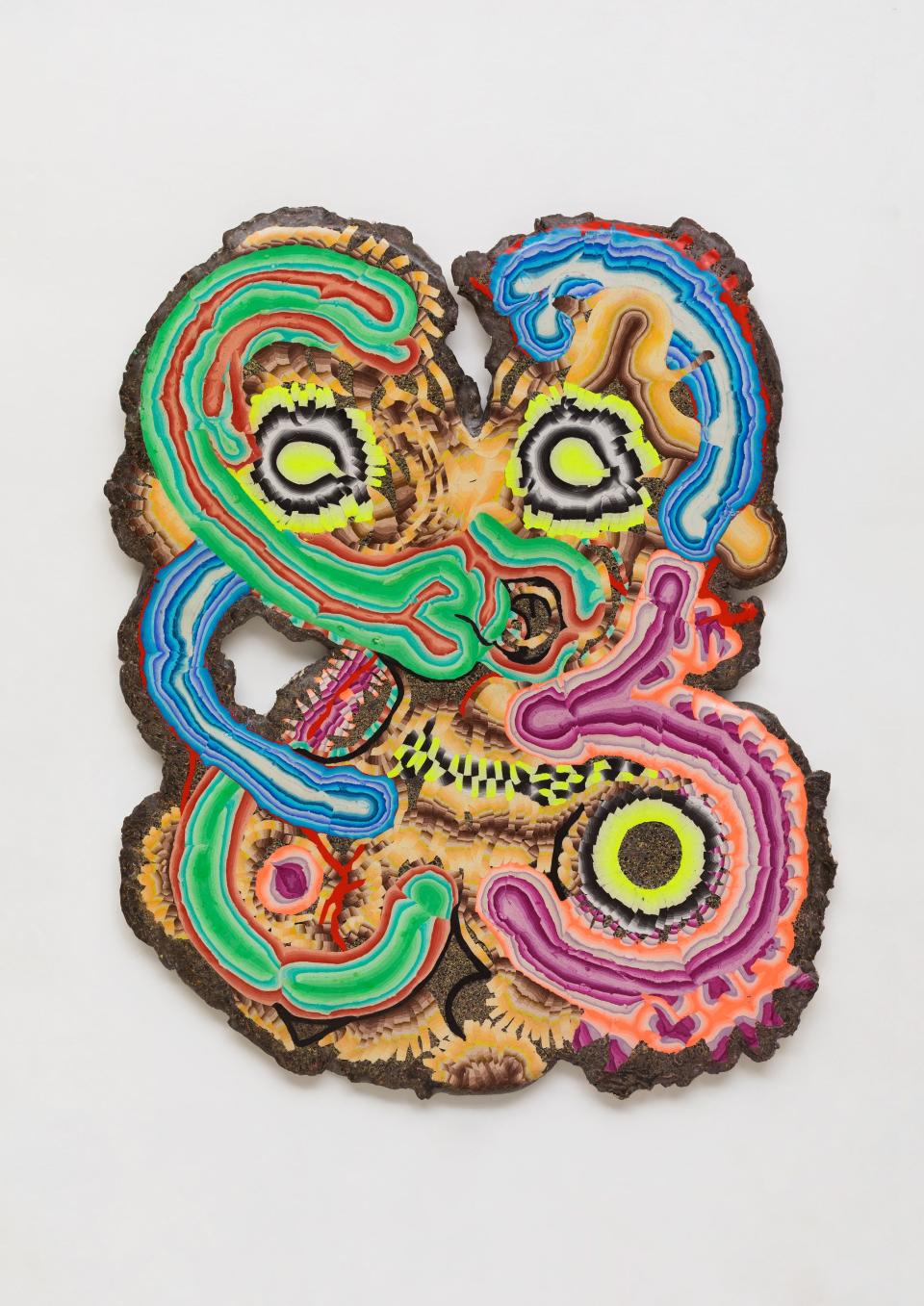

Another excavation is taking place in the sixth-floor restaurant, where my crew leads me into an immersive installation by the German-born artist Kerstin Brätsch. Here, slablike abstractions made from pressed stucco in vivid neon colors line the walls, and faux-marble wallpaper at foot level is inset with dinosaurs and grooves of colored gel. Brätsch, who collaborates with glassblowers and other artisans to explode the conventions of painting, is influenced by everything from Old Masters to Japanese animation. She was unfazed by the prospect of exhibiting her work in a utilitarian environment “where art and daily life intertwine,” as she puts it. “I hope the experience is playful, mysterious, a little magical, intimate, and not corporate.”

We pass MoMA’s existing cafeteria, which is also getting a revamp, this one at the hands of a three-person Dutch graphic design group, Experimental Jetset. The trio researched historic artist-led restaurants, such as Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Jean Arp, and Theo van Doesburg’s 1920s Café L’Aubette in Strasbourg, whose original paint colors they sourced to create panels based on the shape of Philip Johnson’s windows for MoMA’s façade. As we reach the grand gesture that is the museum’s new-minted ground floor, the sculpture garden is having its weighty contents reconfigured—I spot an Isa Genzken rose waiting to be planted. A new acquisition, Haim Steinbach’s large-scale text piece Hello. Again., from 2013, has been mounted on a wall.

“My criticism as a visitor to MoMA,” says Diller, “was that it felt like I walked a quarter mile into the museum before I saw art.” No longer. Now the lobby is less of a tunnel connecting 53rd and 54th Streets and more of an open, airy space hosting installations of its own. The French artist Philippe Parreno gets star billing here with an environment that includes two marquees, some 120 moving lamps, a screen, and interactive sound.

Like the other commissions, Parreno’s takes a non-prescriptive approach to the way viewers look at art, acknowledging that this can be anything from focused and in-depth to spacey and oblivious. A final commission on the third floor hosts an open invitation to dream, courtesy of national treasure Yoko Ono. Here, beanbags are scattered and sky-blue panels bear a poem opposite a long window engraved with a Babel-like incantation, showing the words peace is power in 24 languages. Turns out, it can be surprisingly hard to translate.

This piece has been updated. An earlier version incorrectly stated that the cost of the 2004 renovation was $858 million. In fact this was the total for the capital campaign.

Originally Appeared on Vogue