How My Mom Taught Me to Write…with Her Sewing Machine

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

On a recent unseasonably hot day, my sister and I were enlisted to help to sort through my parents’ garage, overflowing with decades worth of junk…taking a break from our day jobs—I am a writer; my sister is a college adviser. “Maybe we should just get rid of everything without looking through it,” she suggested. Part of me agreed, but then I spotted my mother’s old Singer sewing machine, the ivory-colored one with a thick coffee-brown stripe across the top, that familiar silver dial. I stared at it with such intensity that suddenly I was 10 years old, watching my mother sit at the end of the dining room table in front of that Singer.

I loved watching as she used her teeth to cut thread and pressed her foot on the black pedal. That machine purred. It was a pair of pants for me, a shirt for my sister, or even curtains that had her full attention. When she hovered over that Singer, squinting at the needle, using her palms to even the fabric, I could tell she was transported to a different world. It was one far from her daily work as a housekeeper for wealthy families in the Boston suburbs, far from the endless responsibilities of being an immigrant, wife, mother, daughter, and sister.

But—come to think of it—she hadn’t sewn in years. “What happened to your new one?” I asked her. I was thinking about the computerized sewing machine with the fancy buttons; a workhorse, it really got the job done.

“It’s…there,” my mother said, waving the back of her hand toward the house.

As one of the oldest of seven kids, my mother was the first to move from Guatemala to the United States. It was the seventies, and Guatemala was in the midst of a 36-year-long civil war. But, as my mother jokes, the more pressing war was the one between her mother and father. He was an alcoholic and rarely kept a job. The family pinched resources wherever they could: My mother and her sister literally shared one tuition to attend school—my mother attending classes in the morning and rushing home at lunch to hand over her uniform (whose holes she mended) to my aunt, who would attend the afternoon classes. Every evening, they would share notes. When my mother turned 18, she left for the United States.

She landed in Los Angeles, where she would spend years working as a live-in nanny, sending money home, learning English. Once, she was so desperate for her native language that she looked up a completely random Spanish surname in the Yellow Pages and dialed. Mrs. Santiago picked up and spoke to my mother in Spanish for an hour! So homesick was my mother that she contemplated returning to Guatemala, ripping herself like a seam from her new life in America. But when she received a telegram in English with five words, Your father is very ill, she didn’t know what “ill” meant, and by the time she could look it up, her father had died. Unable to care for him, she had no choice but to stay and work and support her family back home.

As a young woman in the U.S., she grew to love fashion. The round-edged sepia photographs of her during this time showed flirty poses beside palm trees, on the boardwalk, or on the beach, as she modeled dress after dress, bell-bottom jeans, crop tops, even swimsuits. She wore headbands, scarves, and chunky platform heels. With only a needle and thread, she was able to alter and repair, developing her passion that transcended geography, language, culture. She discovered self-expression through clothes and accessories, allowing her to feel beautiful in her new country.

Stitch by stitch, she made a life in America. She learned English, saved money, moved across the country to Massachusetts, married my father, became a U.S. citizen, raised three daughters, bought a house. For Christmas, the year she was pregnant with me, she longed for a sewing machine of her own. But at $200, it was too expensive. That spring, when I was born, my mother told my father, “With two girls, I need to sew.” He laughed, and together, they drove to Sears; they would make it work. With it, she thrived, making her family clothes—hemming jeans, shortening dresses, and adding style to her home by sewing curtains and pillowcases. Stitch by stitch. Year after year. Eventually, she even went back to school, earning her G.E.D. when I was a freshman in high school. She insisted on borrowing my older sister’s cap and gown for photos at the local Sears portrait studio. The gown was too long, so naturally, she hemmed that, too.

When my sister and I helped our parents clean out the garage, our faces and arms covered in dust and dirt, we assessed each item for its worth—a blender missing its top (toss it), a comforter eaten by moths (toss it), a plastic sled (keep it). My sister pointed at the broken Singer and scrunched her nose. Wait. No. We couldn’t…

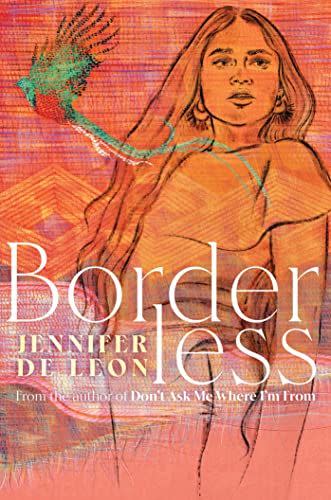

Borderless

amazon.com

This was my mother’s keyboard. Instead of words, sewing was her language and her art. The glint of the needle was her blinking cursor. I stared at that dusty Singer and realized that watching her make the most of what fabric she has been dealt has been the greatest honor of my life. Even though I can’t sew, not even a button, it was in watching her at the kitchen table, when I sat at the opposite end, that I learned to stitch together words. Sentence by sentence. Page by page. And what is writing if not making something from nothing?

In that moment in the humid garage, my mother and I both lunged toward the machine, reaching for all that it had created, all that it had sewn together. Even though it no longer technically worked, we knew that Singer was staying.

Jennifer De Leon is the author of the novel Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From (2020) and the essay collection White Space (2021). She is the editor of the anthology Wise Latinas (2014) and an associate professor of English at Framingham State University, and instructor in the creative writing and literature graduate program at Harvard University. She founded Story Bridge LLC, which brings people together from all walks of life to shape, share, and hear each other’s unique stories. Her YA novel Borderless was published in April.

You Might Also Like