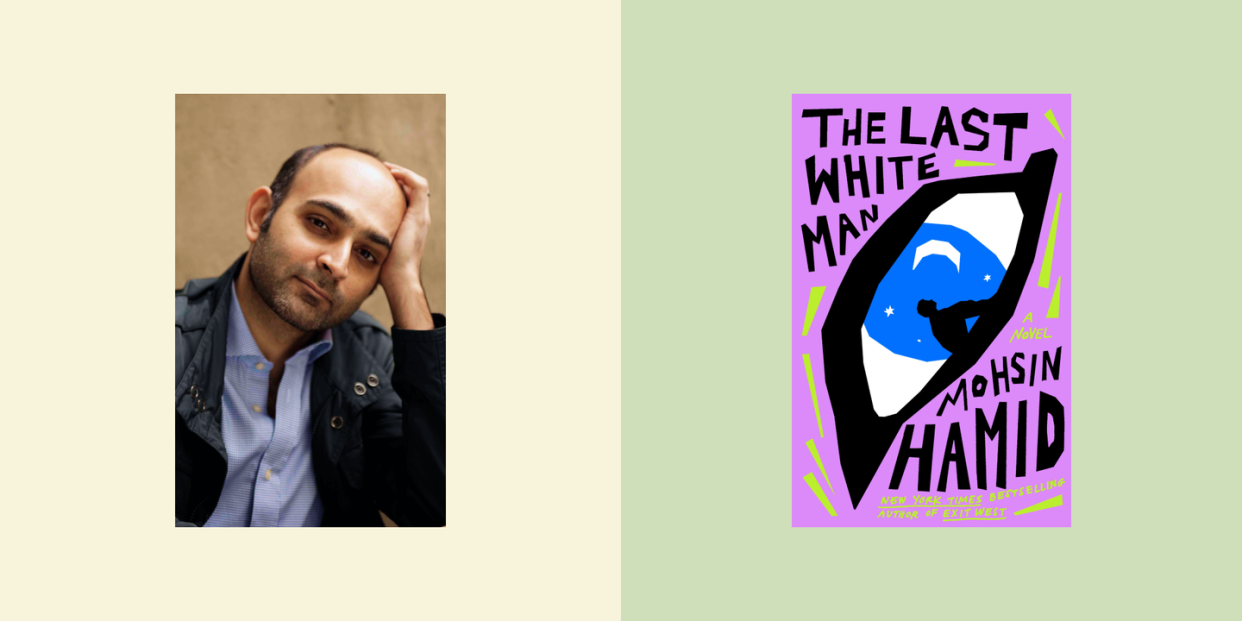

Mohsin Hamid’s “The Last White Man” Is a Provocative and Spellbinding Fable with a Nod to Kafka

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What do Kafka’s Gregor Samsa and C.S. Lewis’s Eustace Scrubb have in common? Mohsin Hamid alludes to both in the first paragraph of his provocative, mellifluous new novel, The Last White Man, a fable about race set in an Anglophone country. Samsa, the protagonist of The Metamorphosis, famously morphs into a cockroach; in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the third Chronicle of Narnia, Eustace wakes from a nap on a craggy island, magically changed into a dragon. Hamid’s opening deliberately echoes the language of Kafka and Lewis, teeing up a spellbinding tale that peels back transformations both great and small.

This is familiar terrain for Hamid; his previous novel, Exit West (2017), drew on Narnia to probe the global refugee crisis. A bestseller, it was named a New York Times Best Book of the Year, and went on to win the Los Angeles Times award for fiction and the Aspen Words Literary Prize. (Barack and Michelle Obama are slated to produce a film version, starring Riz Ahmed.) As The Last White Man commences, Anders wakes one morning, Samsa-like, “to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown.” Twentysomething and fit, he immediately calls Oona, a former high school friend, now a friend with benefits. She rushes over, startled by the figure who no longer resembles her partner, but in bed, she summons an unexpected desire and tenderness for him.

He works at a gym, where his colleagues shun him and a diminutive Black janitor offers glances of sympathy; gradually, Anders grasps clues about what it means to be marginalized in that hypermasculine, all-white space. He’s not alone: Soon reports flood in from around the globe as Caucasians mysteriously darken and the ratios of societies tip toward people of color. The Last White Man deftly plays with an evolutionary irony: Race is a biological fiction, and as the Human Genome Project revealed, there’s more genetic variation among individuals within populations than between disparate populations themselves. As a social category, “whiteness” arose roughly 6,000 years ago on the Russian steppes with the emergence of the fair-skinned Yamnaya culture, likely inventors of the wheel. In most biological respects, darker pigmentation is the default position of our species.

Hamid is not just concerned with whiteness, though; as his title intimates, he’s also bearing down on manhood. Anders’s father is dying of cancer; the abrupt racial divide prises between them like a knife, but ultimately their relationship prevails: “Anders…came first, before any allegiance, he was what truly mattered, and Anders’s father was ready to do right by his son, it was a duty that meant more to him than life, and he wished he had more life in hum, but he would do what he could with what little life he had.” Oona, still mourning the premature death of her addict twin brother, confronts a similar challenge in her widowed mother, an elderly racist who’s convinced there’s a Great Replacement conspiracy afoot, and cheers on the militaristic maneuvers of militias. Riots explode, forcing lockdowns. Tensions roil across generations, cities, nations.

As with Exit West, Hamid’s technique is indelible, a buoyancy that belies the gravity of his themes. Most (not all) of his paragraphs are single beautiful sentences that purl and flow over punctuation scattered like pebbles, with repetitions and cadences that tow the reader forward, gently. He deploys commas with the subtle bravura of Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies; the effect is to make the immaterial—the inconceivable—real.

With these long sentences-as-paragraphs, Hamid also underscores the persistence of grief, like a river that carves through our lives. “Behind Oona’s house the moon was visible,” he writes, “a little less than full, a pregnant belly moon, that was what her father used to call it, and stars were scattered across the sky, and Jupiter was there, bright, and Saturn, not quite so much, and she followed their arc, looking for Mars, but there were trees in the way, and Mars was nowhere to be seen, and not seeing Mars made her think of how frigid space was, how inhuman, a lifeless void, dead, like her father, and like her father who had followed him, who had never gotten over him, and this train of thought unmoored her, making the earth less reliable an anchor, her connection to the grass under her bare feet less firm, and she felt the pull of their absence, her brother, her father, pulling at her, the nothingness that had taken them, that takes us all, obliterating us, and then a ringing, a ringing that stopped, and Anders answered her.”

Hamid has spoken of his relationship to whiteness as something he accessed with confidence, if not comfort, prior to 9/11. Born in Lahore, Pakistan, he lived in California as a child when his father was enrolled in a doctoral program at Stanford. The younger Hamid came back to the United States for college, graduating summa cum laude from Princeton, where he studied fiction writing under Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates, and then pursued a law degree at Harvard and took a high-paying job as a management consultant. After the terrorist attacks, though, his Muslim heritage complicated his presence among the corridors of American elites. His heightened consciousness of religion and race seeded The Last White Man, germinating at the back of his mind while he published other acclaimed books.

As white people dwindle and recede, the novel moves to a crescendo of hope. Despite their personal losses and unraveling of their identities, Anders and Oona build, brick by brick, a family to sustain them. Even a recalcitrant such as Oona’s mother is capable of redemption. The Last White Man may lack the pixie dust of Exit West, but it’s another bracing achievement from a consummate master, its silken prose breathing fresh air into fusty debates about race and identity.

You Might Also Like