The Modest Invention That Let the Grateful Dead Live Forever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article is adapted from the book High Bias: The Distorted History of the Cassette Tape.

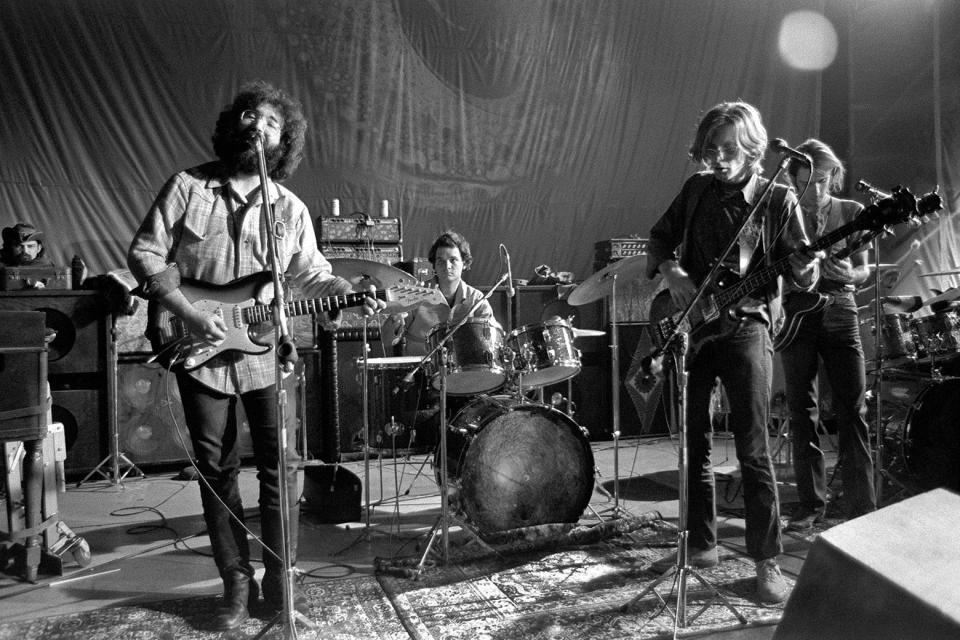

Will the Grateful Dead ever actually die? Though the band ended when Jerry Garcia passed away in 1995, their music keeps getting rekindled, not only by the surviving members but by new generations discovering their legacy. There are many reasons why the Dead became an enduring subculture unto themselves, but one of the biggest might also be the most unlikely: the cassette tape.

Invented by Dutch engineer Lou Ottens in the early 1960s, the cassette tape (and accompanying portable recorder) liberated listeners, giving them a cheap, easy, convenient way to record sound. Soon, fans used it to capture concerts, right when many rock bands were loosening up, becoming more exploratory and more open to improvisation. Any given Dead show could be unique, and tours could include variations in songs, set lists, and instrumentation. If you weren’t there, you could miss moments that might never recur.

It was “an infinite variety of eternally unfolding, metamorphosing, multicolored architectures of shapes, contexts, and messages,” John Dwork wrote in his Deadhead’s Taping Compendium books with Michael Getz. “Journeying through these infinitely intertwined and interrelated architectures, one can access the full spectrum of pure emotions, being states, and sensory experience.” A bit hyperbolic, perhaps, but a sentiment shared by many Deadheads, who wanted to make every stop on this journey. For them, each show was a page in an ongoing, evolving musical diary—or, as taper Dan Huper described to Dead historian Dennis McNally, “a compilation, every night, of every show that went before.”

“I would see them four or five nights in a row and not see a single song repeated,” says David Lemieux, a taper who became the Dead’s official archivist. “Maybe one night they busted out a song they hadn’t played in 10 years, and that made that show extra special.”

“What they did on any night would be unique,” says Robert Wagner, a doctor who got hooked on the Dead as a college student. “So you want to hear them all, and the only way to do that is to have the tapes.”

The tape-trading scene that formed around the Dead began slowly. Those resourceful enough to record shows before the cassette tape came along had to afford, operate, and transport expensive, heavy reel-to-reel decks. As a result, according to some tapers, fewer than 30 audience-recorded tapes from before 1970 have shown up in trading circles. “Finding those early tapes back then was sort of like finding the Dead Sea Scrolls,” taper Eddie Claridge explained in the Compendium. The Dead’s own sound engineers did record some shows themselves, though, and copies of these recordings made their way out to fans.

In the ’70s, Dead show taping gained steam thanks in part to high-end cassette recorders like the Nakamichi 550. Soon, traders formed clubs to build their collections of both audience and soundboard tapes. One of the earliest, the First Free Underground Grateful Dead Tape Exchange, was started by Les Kippel in 1972. It soon spawned another eight clubs just in New York City and upward of 30 more around the country. “A lot of people want to set up exchanges,” Kippel told Rolling Stone in 1973. “I tell them to get cards made up with their telephone numbers on them, but I also insist it says ‘free’ on them.”

That Rolling Stone article, which dubbed Kippel “Mr. Tapes” and boasted about his over-500-hour collection, flooded him with tape requests. “We would have taping sessions where people would come to my house and we’d run tape machine to tape machine to tape machine,” he recalled in the Compendium. “The peak of absurdity was when I had 13 tape machines running at once! Thirteen people there, ‘Okay … Ready, set, put your fingers on the pause button and—go!’ ” One Kippel disciple, John Orlando, even claimed to have quit his day job so he could spend 18 hours a day dubbing Dead tapes. “I had to stay high all day,” he told Rolling Stone. “Or I’d go nuts.”

In 1974, Kippel started a magazine called Dead Relix that spread information about show taping and trading. Articles included advice on how to record, what kinds of decks and tapes to use, and proper trader decorum. There were also sections where fans could list recordings they were willing to trade (mostly by date and venue) or sought to trade for. Usually all that was required to tap into these personal libraries were a few blank cassette tapes and a little money—strictly for postage, not profit. In the first issue of Dead Relix, an editorial insisted that they “in no way advocate the duplication of live recordings for purposes other than free exchange. …Tape trading is based on honesty!”

Dead Relix helped spark a mid-decade boom in Grateful Dead taping and trading. Another spark came, oddly enough, from the Dead’s absence. When the band went on hiatus in 1975, traders suddenly had time to fill out their collections rather than chase down the latest tapes. “When I started [college] in 1975, I probably had about five Dead tapes,” said taper Mark Mattson in the Compendium. “By the time I got my B.A., I had to move almost a thousand tapes.” Once the Dead returned to touring in 1976, their fan base had increased due to tape trading, and there were enough tapers to cover every concert. It’s likely that every show for the rest of the band’s existence was recorded by at least one member of the audience.

The community was also boosted by more fans creating clubs and magazines dedicated to Dead tape trading. Colleges in particular were a hotbed. In 1979, at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, John Dwork started a Grateful Dead Historical Society and an in-house newsletter called DeadBeat. After graduating with perhaps the first-ever undergraduate degree in Frisbee, he started the Terrapin Flyer, which later morphed into the full-fledged magazine Dupree’s Diamond News. Alongside In Concert Quarterly, Golden Road, and others, it offered a wealth of Dead concert information, reviews, taping tips, and want lists.

By the 1980s, anyone interested in the Dead beyond their official studio recordings had endless opportunities to start up a tape addiction, and the taper community grew exponentially. “I was living in my mom’s house, and virtually every day an envelope or a box of tapes arrived,” remembers Lemieux. “It was as exciting as Christmas morning.” Swaps happened in person too: Trader Paul Scotton recalls taping parties where, “if you showed up with cords and a deck, you could plug in and we’d do it until we couldn’t stand each other anymore. It could literally go on for days.”

As the scene expanded, some resentments festered between veterans and newcomers. “Some people, though not all of them, were very protective; they viewed their tapes as intellectual property and weren’t going to trade with just anybody,” explains Wagner. “But when I became a taper myself, I gave copies to anyone who wanted them.”

“I think it definitely was part of a closed club, but it was something that most of us loved to share,” agrees Lemieux. “We didn’t feel superior, certainly not elitist, just different.”

It was understandable that some tapers would be protective, given how much work it could take to make a tape. Before their 1975 hiatus, the members of the Grateful Dead were somewhat resistant to audience recording, and some tapers claim that Dead roadies cut their microphone cables when they were discovered. In response, tapers devised stealth ways to record shows, spreading gear among different attendees as they arrived, or stuffing entire mic stands down pant legs and claiming to be disabled. Once inside venues, tapers hid decks under seats or coats, pulling them out only when the lights went down, or venturing into bathroom stalls to assemble their recording setups.

Eventually, the Dead warmed up to audience taping. When queried in 1977 about the phenomenon, Jerry Garcia at first bemoaned unauthorized recordings, until he realized the interviewer was talking about trading live tapes, not selling bootleg albums. “Oh, [live] tapes I don’t care about—the tapes are totally cool,” he said. “I spend a lotta time in bluegrass music doing the same kind of stuff: swapping tapes and doing all that.”

“We could either let them come in and tape and take it with them, or we could become cops and take away their machines,” drummer Mickey Hart told Billboard decades later. “We had a meeting and said, ‘We don’t want to be cops!’ So we let them do it.” Eventually, tapers could set up their gear out in the open at Dead shows without hassle from the band’s crew, even when the lights went up.

Unfortunately, security at venues was less lenient. Even though Dead sound engineer Dan Healy would tell guards that the band didn’t mind, tapers still often had to hide their gear in clothes, bags, and even wheelchairs to safely enter shows with everything they needed to record. Taper Frank Streeter remembered bringing his gear piecemeal in the clothes of five different attendees, who would meet in the bathroom, disrobe, and assemble it all. Some smuggled mics inside of shampoo bottles or sandwiches; others buried gear under floors or hid it in janitor’s closets between shows during multinight Dead stands. It made things difficult, but it also kept the underground nature of audience taping strong. This was a community operating outside normal channels, using cassettes to circumvent the system.

It was also a community that turned show taping into an art form. All the decisions that go into making a tape—what gear to use, where to stand in the venue, how to place microphones—came to reflect the personality of each taper and colored the experience of trading and listening. “It becomes a creative art, which I didn’t necessarily anticipate when I started doing this; I just wanted the music,” says Wagner. “But eventually my ear became trained, and I learned from other tapers to listen to each tape you make and try to make it as good as you can.”

There were also craft skills that came with experience. “You want to know where you were in the set, and where the next break is coming so you can flip the tape and not cut off a song,” says Scotton. “You can only know that by going to a lot of shows and making a lot of tapes.” As Dwork put it in typically dramatic fashion in the Compendium, “We have mastered the martial art of equipment sneaking, tape flipping at the speed of light, superior ticket ordering, insane tour scheduling, even sending our recording decks on tour while we stay at home. We’ve developed our own language, our own culture, and, for some, even our own spiritual dimension!”

There was also an art to the archiving and documentation of Dead tapes. Each taper had their own approach to labeling, sometimes adding details of show dates, song titles, gear used, and where mics were placed. Some were happy to have different label styles adorning their racks; others insisted that tapes be sent to them with the covers still blank so they could add information in their own preferred manner. Many were so detail oriented that they could be seen, as Wagner puts it, as “hyper-focused savants.” “If I taped a run of, say, 12 shows, I could remember where I was at each one,” he recalls. “I could rattle off the top of my head the set list for every one.” Wagner’s obsessions were rewarded when he made a last-minute decision to drive to a Mississippi gig in 1978. He turned out to be the only audience member there who was taping. Later, he discovered that the Dead’s own recording didn’t survive, so he owned the only document of that show. Originally drawn in by the uniqueness of every Dead concert, Wagner now had something unique of his own to contribute to their vaults.

As tapers continued to refine their art and the Dead continued to accept them, it became common to see a nest of microphones thrust up high in front of the soundboard, and Healy had trouble seeing the stage as he mixed the band. He also got frustrated hearing stories of tapers stealing seats from nontaping fans by claiming they got there first to set up all their gear. In 1984, during a three-show Dead stint in Berkeley, California, Healy unveiled a solution to these problems: a dedicated section of seats behind the soundboard for tapers, for which tickets could be purchased ahead of time through the mail. The idea brought some immediate advantages: Tapers could bring in equipment with ease and could more quickly share recordings, sometimes chaining their decks together to access one common audio signal.

But there were downsides too. Veteran tapers complained that the section drained some of the fun out of the experience, with all the gear blocking movement and tapers policing people in the section to stay quiet. Even worse, some tapers felt the sound quality of what they captured from behind the board was inferior to what they got when closer to the stage. “To sit in the tapers’ section and get a terrible recording wasn’t even worth going to a show,” taper Dougal Donaldson said in the Compendium. “To ghettoize all tapers like that was almost a punishment.” In response, many tapers ventured back to their previously preferred spots, resurrecting old ways to record without being noticed. It was perhaps a blessing in disguise, allowing the community to maintain its underground nature even as the taping phenomenon became well known.

Regardless, the Dead’s official acceptance of taping publicly acknowledged a crucial part of their fan base. It signaled to tapers that the group appreciated its most devout followers. “The audience is [as] much the band as the band is the audience,” drummer Bill Kreutzmann told McNally. “The audience should be paid—they contribute so much.” “All this trading made people more and more interested,” says Scotton. “They realized it wasn’t the same show over and over, so they started packing halls even more.” “I also think the Dead firmly knew that the strength of their cultural identity was in their live performances, and it was very hard to ‘get’ the Grateful Dead from their studio records,” says Lemieux. “I love the studio records, but the power, the thing that would turn you on and literally change your life, was hearing the Dead live in concert.”

Into the late 1980s, the Dead’s popularity certainly grew, whatever the reason. Despite scoring just one hit—a 1987 appearance in the Billboard Top 10 by a studio recording of the live staple “Touch of Grey”—they became one of the most financially successful touring bands around, taking in $50 million a year from shows during their peak. They sustained a large audience no matter how often they released studio albums—which, unlike with many other bands, the tours weren’t really meant to promote anyway.

Throughout all these years, soundboard tapes continued to circulate. Some tapers sought the best-generation versions of those recordings; later, after the advent of digital recording, some mixed soundboard recordings with audience tapes for the best combination of musical quality and ambience. For many, audience tapes offered a more “real” version of a show, less sanitized than the sound of the instruments sent directly to the mixer from the band’s onstage mics and amps. “A soundboard tape might be perfectly balanced, but it often lacked something,” says Wagner. “The audience tapes made you feel more like you were there, with the crowd noise and hall ambience. Under good conditions, that added life to the tape.”

In the 1990s, the Dead began releasing official soundboard recordings. Dick Latvala, a former tape trader who had amassed a collection of 800 shows on reel-to-reel, became the band’s official archivist and launched Dick’s Picks, releasing concert recordings from the band’s vast vaults. He kept it going after Garcia died, and when Latvala himself passed away in 1999, Lemieux replaced him. After getting a graduate degree in film preservation, he contacted the Dead to ask if they had a video archive of their concerts. The band hired him to help catalog that section of their vault, making him a natural choice to take over the entire Dead library after Latvala died.

Lemieux continued Dick’s Picks until 2005 and launched his own Dave’s Picks series in 2012. By then, the band and most tapers had moved away from cassette, using digital formats as early as the 1990s. But Lemieux still uses the Dead’s own cassette recordings for some older releases in his series. “I go back and I listen to my [digital audio tapes] from the early nineties, and they have tons of problems, dropouts and so forth,” he says. “Whereas when I put on any of my cassettes from the late eighties, they sound as good today as the day they were recorded.”

Long after cassettes faded from the scene, the Grateful Dead trader community remained strong, and friendships forged through tape trading continue to endure. “That was part of the experience of going to a show, seeing old family and friends, running into people you hadn’t seen in thirty shows,” Scotton remembers. “When you listen to the music, you remember those times. It sends chills down my spine when I hear it. There are times when space and time don’t matter, you’re just off somewhere—and these guys were there, just night after night after night. It’s remarkable.”