MIT and Ministry of Supply Test Shape-Shifting Dress Activated by Heat

Upcycling may not be the only way for garments to shape shift.

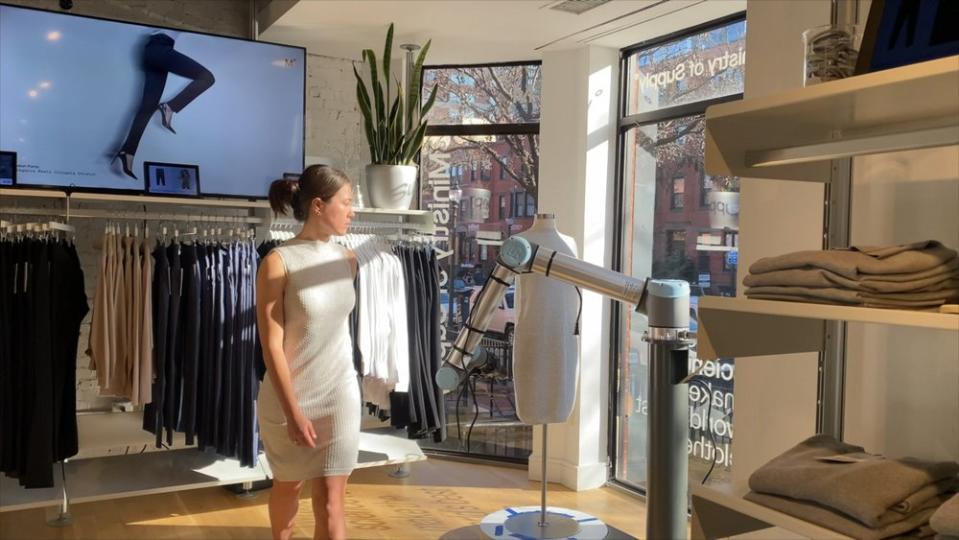

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Self-Assembly Lab have developed technology that allows a garment to be altered or customized by heat administered by a robot.

More from Sourcing Journal

The researchers used active yarns made of polyester that intentionally shrink when exposed to high degrees of heat, creating a tightened or cinched look that can be used to meet individual consumers’ sizing needs or styling preferences.

The research team piloted its technology with fashion brand Ministry of Supply. The two have previously teamed up on other garments, like sweaters and face masks.

The dress MIT and Ministry of Supply created starts out as a shift dress that can be altered to take on other silhouettes, like A-line or bodycon. A robotic arm provides the heat needed to modify the dress to the consumer’s specific preferences.

Sasha McKinlay, a researcher at MIT and project lead on this initiative, said the technology could help break down human and cost barriers for creating garments.

“The goal of the project was to have a garment come out of the [knitting] machine that would be able to be customized or made bespoke in a process that wouldn’t be as labor intensive or material intensive as cut and sew,” McKinlay said.

The researchers said that though the technology piques consumers’ interest, it also has potential sustainability impacts. For instance, if a customer wears the dress one way for several months but later wants to add pleats, shift the silhouette slightly or make other adaptations. Those changes could shift the garment into a whole new piece, eliminating the need for further purchases.

McKinlay said the idea of creating something that could be refashioned—rather than thrown away—drove much of her interest in innovating on the project.

“I think the problem with fast fashion is that it addresses a human need to express oneself [through] their garments. I believe that people should be able to express themselves, but I think that it has taken [a major] toll on our environment, unfortunately. The fashion industry is hugely responsible for that because they just keep changing tastes and keep changing fashions and people are just trying to keep up; they’re also trying to understand themselves as they grow up,” she told Sourcing Journal. “I think if a garment would be able to at least address some of those changes or be able to evolve with a person even slightly, I think it would have a huge sustainability impact that I think is worth exploring.”

Because the active fibers in the knit dress are made from polyester, and the base fabrics in the dress are a viscose poly blend, the yarn used for the dress is not currently biodegradable, McKinlay said. However, she noted that the garments could potentially be recycled by facilities that can handle polyester.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the behaviors that make this work…are behaviors in synthetic fibers. Making those fibers biodegradable would mean that we would need to add additives. We’ve explored that option, but I think that additives are so new that we don’t have the data to back it up. But the recycling route has been backed by data, so in the future, this would be a monomaterial made of polyester or nylon that can be recycled entirely in one piece.”

The team did not use reversible fibers for this project because McKinlay said those materials are still in their infancy, and thus, a long way from commercial viability. That means that once the garment has been shrunken down to size, it cannot be made larger again.

McKinlay said though she knows the research has valuable applications around style and fit, some pieces of the puzzle still need to be ironed out before the technology becomes commercially viable.

One such issue may be supporting technology. In the limited trials the Self-Assembly Lab has done with Ministry of Supply, researchers used a static mannequin, which meant that the heat treatment would tailor the garment to the shape of that mannequin, rather than an actual consumer’s body.

For dynamic sizing, McKinlay said, the researchers believe they would need a technology-enabled mannequin that changes sizes to mirror a consumer’s body. That’s because a human would not be capable of withstanding the high degree of heat the robot uses to tailor the garment.

If the type of technology to influence consumer experience becomes more widely available, McKinlay said researchers would need to understand whether consumers would wait for their clothes in stores. In a public-facing trial with Ministry of Supply, it took the robotic heat arm about 35 minutes to completely finish working on the garment.

McKinlay said that time could decrease if the researchers optimize the machinery strictly for speed, but it remains to be seen whether consumers would wait for off-the-rack clothes to be tailored in real time.

Even if consumers don’t mind waiting the few minutes it takes to alter their garment, McKinlay said consumers’ ideas around clothing’s value—or sometimes, lack thereof—could mean that they lack interest in a long-life garment like the dress MIT and Ministry of Supply collaborated on.

“We need customers to be able to change their ideas about owning clothes. People hardly ever think about going to the tailor anymore. If they’re dissatisfied with their clothes, they usually just decide to throw them out,” she told Sourcing Journal.