I Miss Smoking

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Esquire. Upgrade your membership to All Access and read every Esquire story ever published.

“I do not make much sense without tobacco.”

—John Cheever, The Journals of John Cheever

My mother was a pack-a-day smoker for much of her life, and as a child I hated it. Our house reeked. The car was worse. She’d hotbox my siblings and me by neglecting to roll down the windows. Once or twice, by accident, she brushed me with a lit cigarette. As Henry Fonda put it about one of Hollywood’s most furious smokers, “I’ve been close to Bette Davis for thirty-eight years—and I have the cigarette burns to prove it.” We’d get revenge on my mother, when we were teenagers, by slipping those little slivers of exploding loads into the tips of her Merits. My mom is the sweetest woman in the world and does not have a big temper. But when one of her cigarettes would detonate in her face, bang, leaving her looking like Wile E. Coyote on the wrong end of a spherical Acme bomb, she’d lose it. We’d run away at hilarious, cranked-up, silent-movie speed.

I wasn’t a smoker in high school or college. But, reader, I married one. My wife, Cree, looked more than good with a cigarette, and she still does. She’s tall and has long, dignified hands, richly veined as if they were hydraulic things. Smoking has always favored people with excellent mitts. Men with long, tapered fingers—Peter O’Toole, Barack Obama, the theater critic Kenneth Tynan—were made to hold cigarettes. So were bruisers like Charles Bukowski who used smokes to show off their knuckles the way certain women know how to flash their ankles. The idea of Donald Trump holding a cigarette, two of his Vienna sausages around a damp, angry inch of white asparagus, makes you wince. Being around my wife, I began to envy the pleasure she took in smoking. I envy everyone else’s pleasures, all the time. One of the best things about reading, about keeping up with your species, is discovering new ones. I started smoking Camel Lights, as they were then called, in my thirties. I kept it up, about half a pack a day, for a decade. It’s a strange thing, picking up a consuming new vice later in life. You get to have those humiliating apprentice moments—the pulling over to puke after your first real inhales, for example—when you are old enough to recognize what a spectacle you are. Nearly everything that’s worthwhile is odious the first time you try it: coffee, bourbon, Tom Waits’s singing, habaneros, donning a gimp mask (jk!). Acquired tastes are the ones that matter.

On most days, I’m glad I quit smoking. I stank. It was expensive. (In Manhattan, where I live, cigarettes now cost an extortionate twelve or thirteen dollars a pack.) I’d like to be alive to meet my grandchildren and welcome our alien overlords. But there’s so much I miss about it that I grow deeply maudlin just thinking about it all. Something is gone from my life and, more essentially, from the culture—something we’re unlikely to get back.

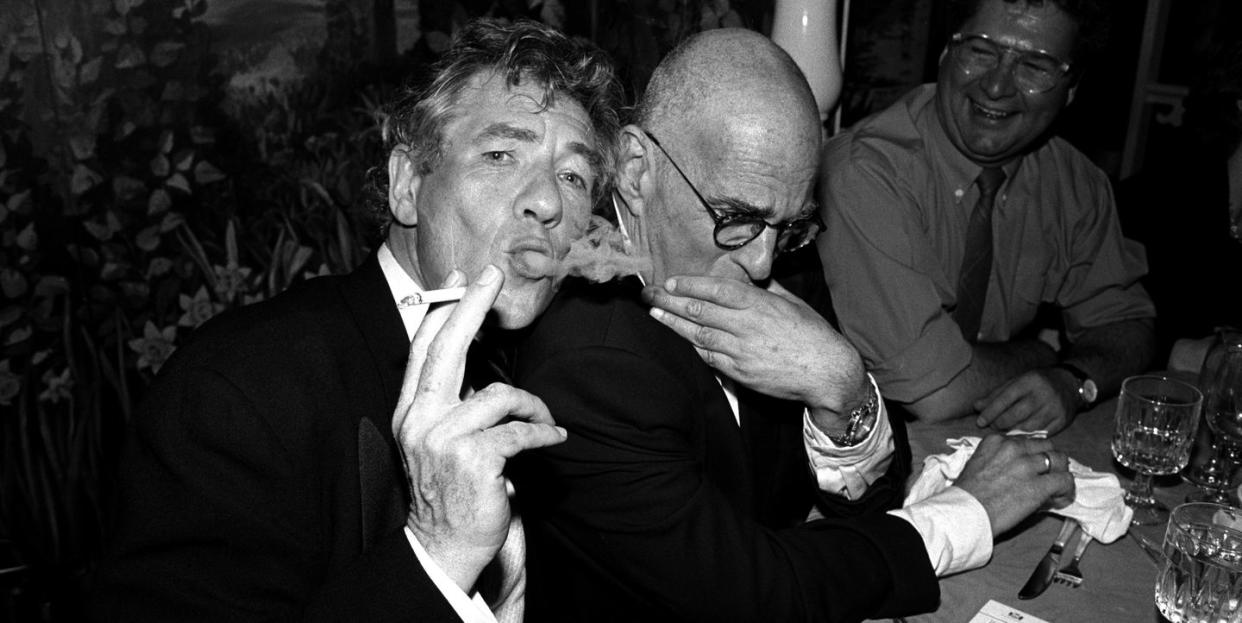

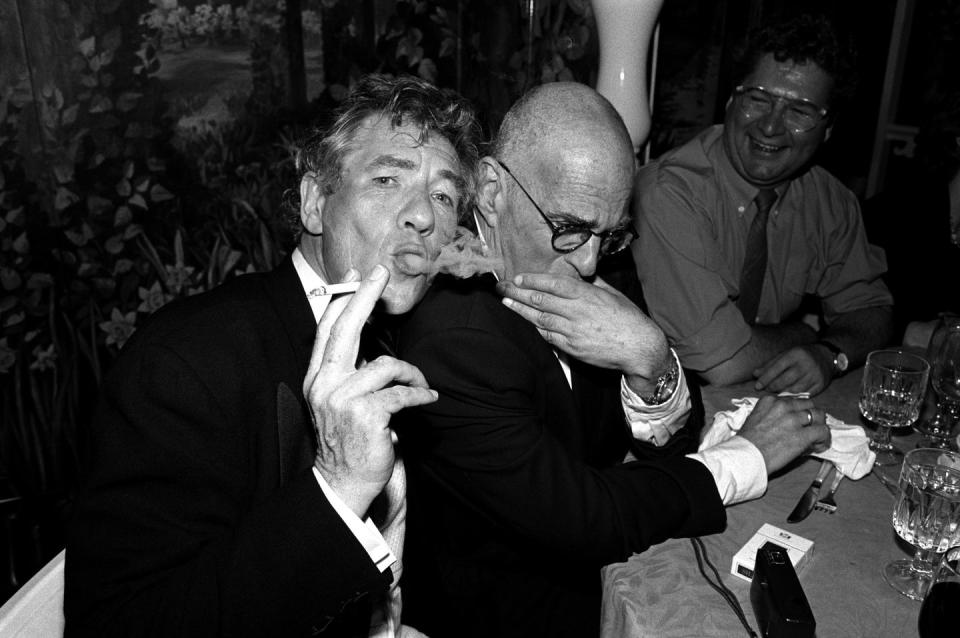

(It hardly seems a surprise that, since Americans largely stopped smoking, we weigh more and flood the oceans with the residue of our antidepressants.) I miss the way cigarettes made people linger around the dinner table for hours. I miss the workaday camaraderie of smoking. I landed the most important job of my life, at least in small part, because I wound up smoking with some people in the stairwell of a big office building during a magazine party. I hit it off with one of those people, and he became one of my bosses. I miss lighting them for women. I’ve got a close female friend, Catherine, who was a sorority girl at Ole Miss. One of the social codes she learned there, she told me, is that while a man lights your cigarette you must stare directly into his eyes.

I miss how cigarettes functioned like clocks, carving out time. They were sometimes put to unusual purposes this way. Who can forget the distressing scene in Taxi Driver in which Jodie Foster lights a cigarette, places it down, and says to a john, “Fifteen minutes ain’t long. When that cigarette burns out, your time is up.” Most of all I miss the ceremonies of cigarettes, the language of them, on the streets and in the movies. I tend to agree with Richard Klein, who wrote in his magnificent 1993 book, Cigarettes Are Sublime, that “cigarettes, though harmful to health, are a great and beautiful civilizing tool and one of America’s proudest contributions to the world.” Klein understands the contradictory nature of cigarettes, the way “they both raise the pulse and lower it, they calm as well as excite, they are the occasion for reverie and a tool of concentration, they are superficial and profound, soldier and Gypsy, hateful and delicious.”

I never again wish to be trapped on a long-haul flight or in a movie theater with smokers, experiences I am just old enough to recall. But bars aren’t the same without them. (“No smoking in bars,” Samantha commented on Sex and the City. “What’s next, no fucking in bars?”) Rock shows aren’t the same, either. There’s deep irony in the fact that when you vape, the stuff that makes your breath look like a cloud of mist when you exhale is propylene glycol, the same stuff used in fog machines at concerts. It’s been linked, in stagehands, to chronic lung problems. I’m of utter mixed minds about vaping. There’s nothing worse than walking behind a vaper on the streets and getting a big cloying blast of crème brûlée or birthday cake or pumpkin pie. This is like walking through a spider’s web of cotton candy; it’s redolent of a megaton syrup-fart. And now that pot smoking is all but decriminalized in many places, the skunk stench of pot perfumes our waking hours. As the columnist Ginia Bellafante wrote in The New York Times, pot smoke is “the signature olfactory experience of New York.” (At least until summer, when it’s urine.) I like pot; for that reason, and for political ones, I’m glad to see the progress that’s been made. But I’m made ill daily from the funk in the air. Odor is subjective. My pot smells okay; yours is oppressive. Chinese food is one of the great scents on the planet, for example, as Chuck Berry pointed out in his autobiography. But not if someone opens a container of General Tso’s chicken behind you in a dark theater or on the subway.

A lot of my friends walk around with Juuls tucked into their palms now. They’re a plausible compromise even if, as a friend likes to say, they make you feel like you’re sucking on robot dick. You can “smoke” them indoors, which makes it feel like the 1970s all over again. It’s hard to know when enough is enough with a Juul. You end up like the narrator of Martin Amis’s great novel Money, who comments, “Unless I specifically inform you otherwise, I’m always smoking another cigarette.”

I realize that this lament cuts against the grain of our moralistic and health-obsessed culture. Don’t @ me, as they say on Twitter. I’m proud of the people who’ve managed to quit. I’m working on my wife, too, if subtly. Whenever I go abroad, I buy her those cheap duty-free smokes, as she asks me to. But I make sure they’re in that shock British packaging, with lurid photographs of ruined teeth and holes in people’s sad wrinkled necks. On certain late nights around the dinner table, however, where we’re making do with whiskey and candlelight instead of cigarettes, someone will start hatching a plan. “When we’re all eighty, we’re going to get together and start on Camel unfiltereds again, right?” I’m all in.

You Might Also Like