The Mighty Rose: The Story Behind Vogue ’s June/July Cover

Vogue’s new issue is unlike any other ever made in the magazine’s 128-year history. With the entire staff in quarantine, no photo shoots were possible; besides, this is a moment to focus on solidarity rather than celebrity. “This is not a time for business as usual,” states Raul Martinez, Condé Nast’s head creative director. “Vogue has always understood and responded to the times.”

The magazine’s new cover features a single red rose, representing, says Martinez, a symbol of “beauty, hope, and reawakening.” It’s also a conduit between Vogue’s past and its present, as it was photographed by Irving Penn, a longtime contributor to the magazine, and one of photography’s great masters. The idea of heritage (as distinct from nostalgia) resonated with the Vogue team in this moment when so many things we have taken for granted have been uprooted.

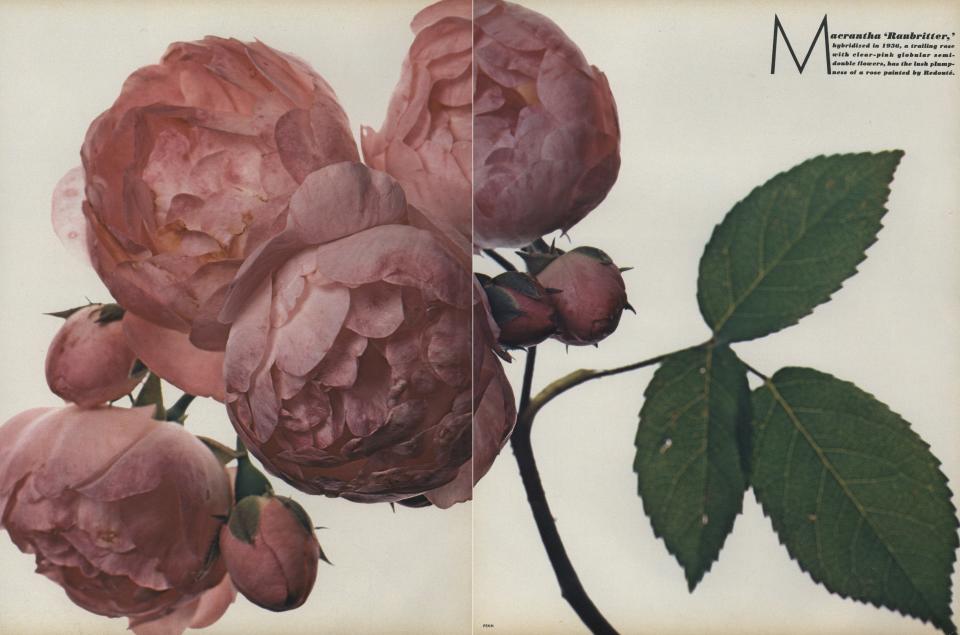

Between 1967 and 1971 Penn created nine flower portfolios for the magazine’s special Christmas issues. The series kicked off with tulips and concluded with Long Island wildflowers. Along the way Penn became fascinated with the subject, and collected his work in the 1980 book, Flowers. These photographs are unrelated to Penn’s fashion pictures, but, generally speaking, it’s easy to draw parallels between flowers and women’s clothing. Both are often associated with romance, femininity, and the ephemeral. (Paul Poiret used a rose as a sort of branding symbol, and Christian Dior envisioned the women who would wear his New Look as “femme fleurs.”)

Penn was interested in the whole life cycle of the flower, from budding promise to ripe fullness and finally crepe-papery decay. He documented all of these stages of being in “Love Flowers: The Rose,” a portfolio published in Vogue’s December 1971 issue, which ran with an essay on the history of the flower by the critic and writer Anthony West (son of Dame Rebecca West and H.G. Wells.)

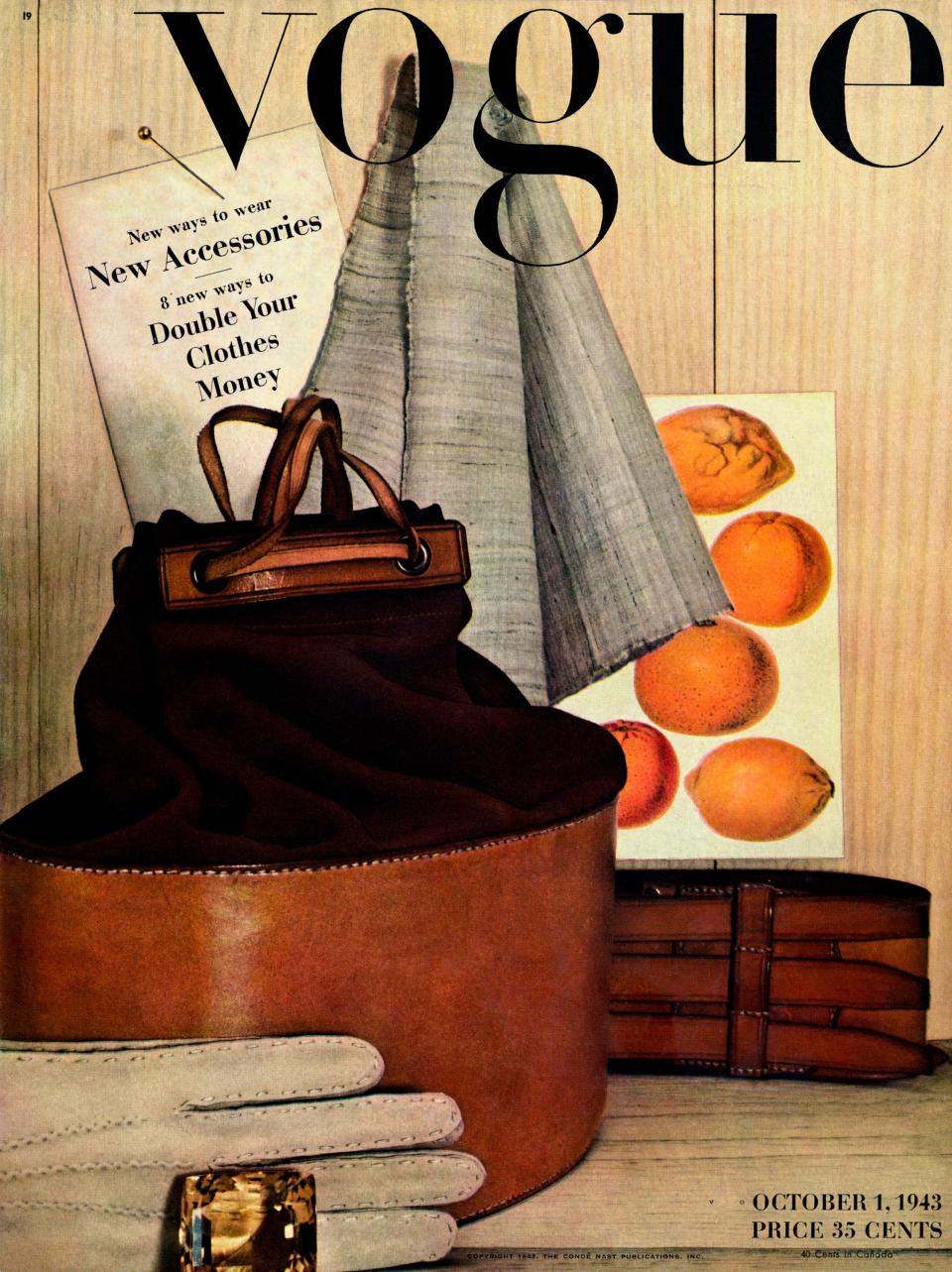

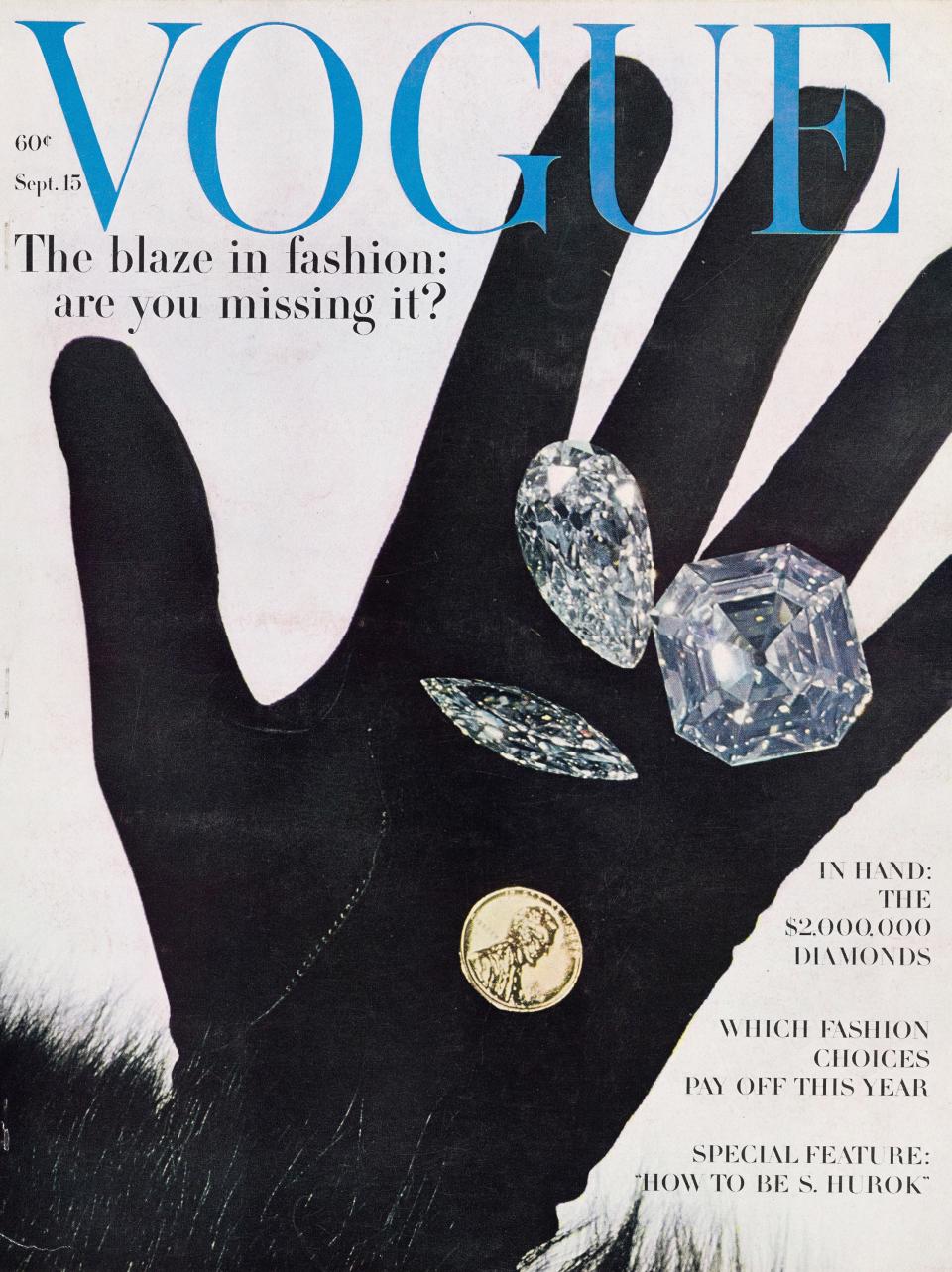

Still, this cover rose can be considered a fresh cut in the sense that it was not previously published in the magazine. It’s old and new at the same time. The back and forths between the present day and the magazine’s archive are, in fact, various and remarkable. This is, for example, the first still life cover Vogue has published since September 15, 1962. That 58-year-old image, which ran with the cover line “In Hand: The $2,000,000 Diamonds” was also created by Penn. And it should be noted that Penn’s very first cover for the magazine, for the October 1, 1943, issue, was also a still life. It was the first color photograph Penn had ever taken. According to the Irving Penn Foundation, with whom Vogue collaborated closely on this issue, “Penn considered [that cover] his beginning as a professional photographer.”

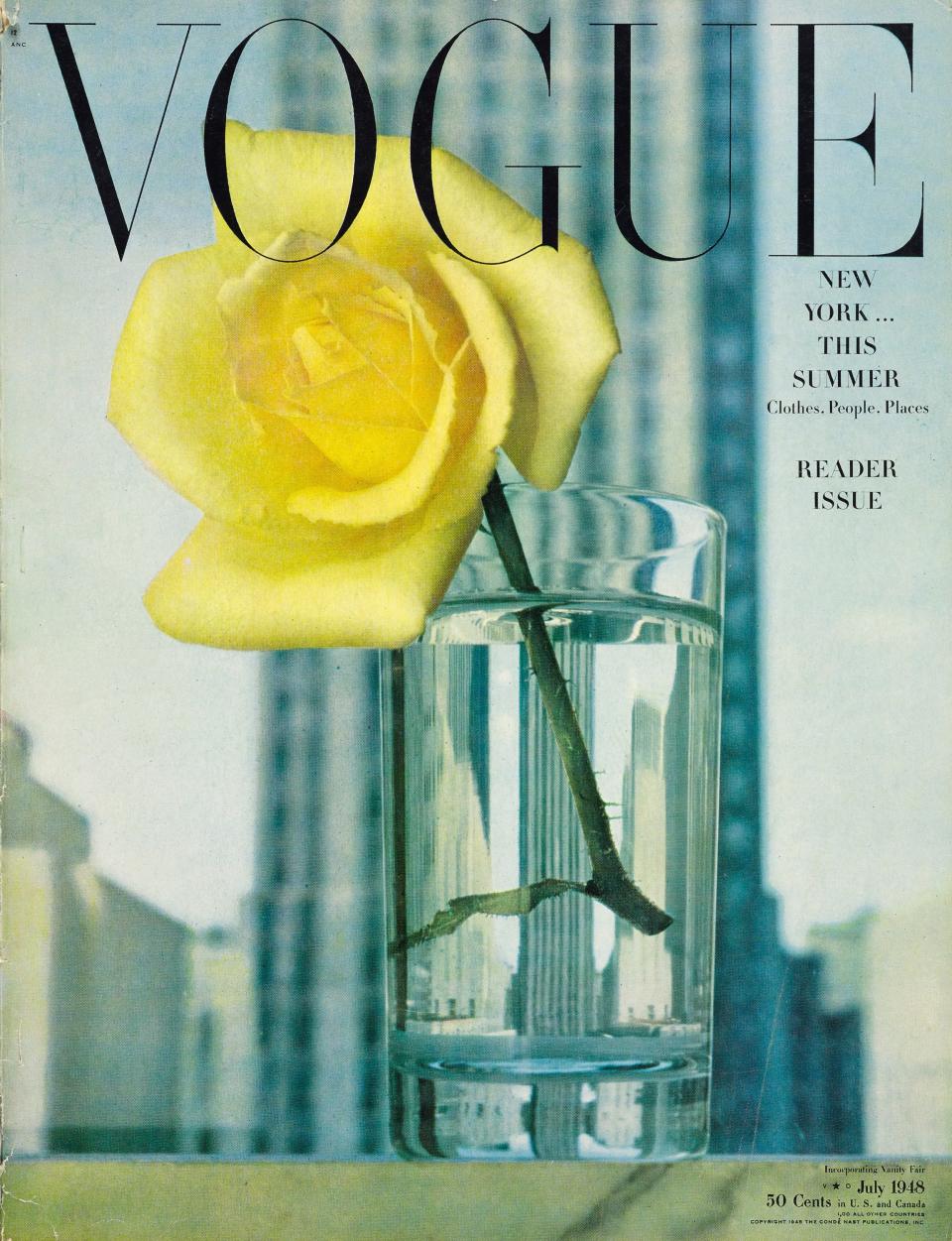

This cover also speaks through time to the magazine’s July 1948 cover, which was also photographed by Penn. Shot on location at Saks Fifth Avenue, it shows a “Golden Rapture” rose standing in a clear glass of water. Towering in the background is a Manhattan skyscraper rising tall—“New York tough,” you might say. The accompanying caption reads: “Seen through a glass clearly: the man-made miracle of the Rockefeller Center towers; against them the natural miracle of a slowly opening rose.”

Our relationship to nature, and our responsibility to care for it, are essential learnings amid this pandemic. Another common thread is the importance of hope and belief in a better future. Like a rose—which is born, says Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s Little Prince, of “good seed”—we must turn toward the sun and search out the light.

Originally Appeared on Vogue