Microaggressions Are Literally Killing Us

Deandre Smith, a filmmaker from Chicago, remembers being one of two Black students in the Columbia College Chicago film program back in 2011. One of his professors, a “liberal, progressive white woman,” often pitted the two Black students against each other by comparing their work. Smith also says his professor once told him that Black men “are known to beat their wives and girlfriends.”

“At the time, I didn’t know how to respond to that,” he says. “I knew it was messed up, but I had to ask myself: Is this racism?” Assumptions from classmates, like that he was inspired by Spike Lee and Tyler Perry as a Black filmmaker, have also filled him with distrust. Smith says that dealing with these attacks has validated his choice to keep to himself. “Non-Black people can hide their thoughts and feelings, and that’s scary to me—that a person can feel and think these things secretly and I won’t even know it,” he says.

“I know it’s not healthy to live in a bubble all the time, but who can you trust?”

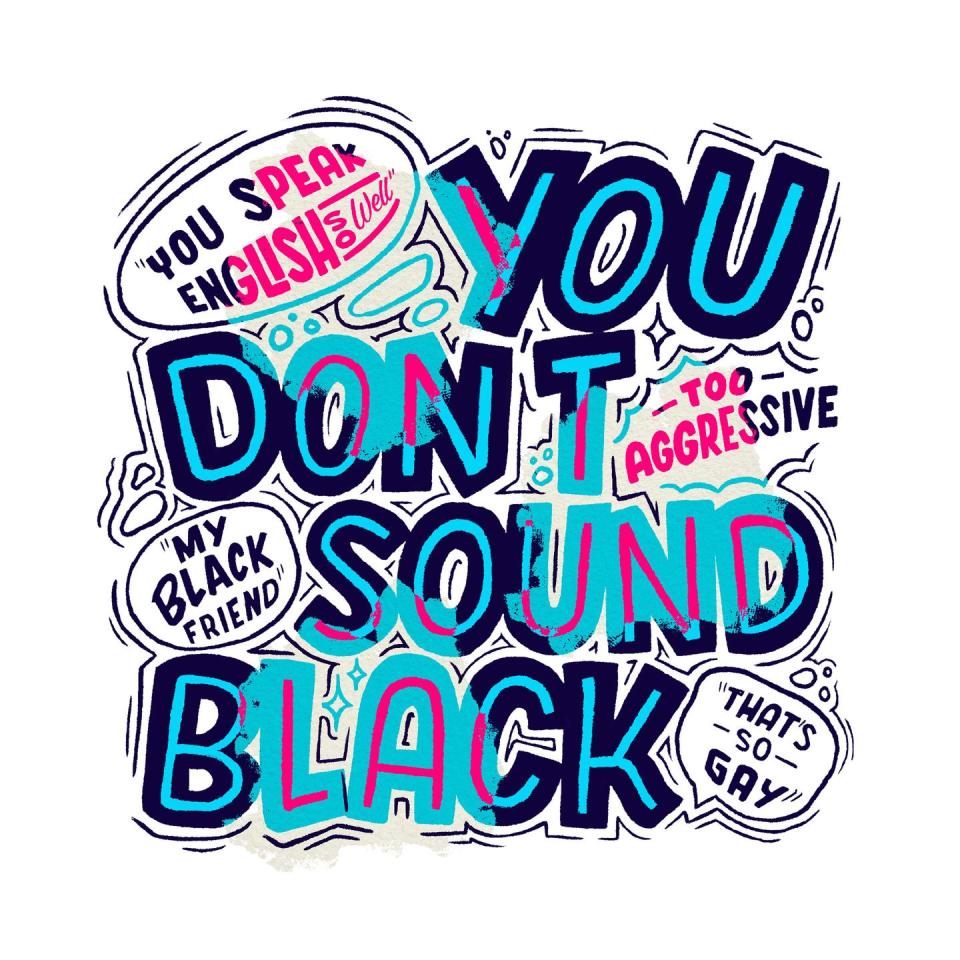

CHANCES ARE you've been the recipient of a microaggression, whether you know it or not. You’ve likely heard the term, too—across the news, on Twitter, in your newly instituted company training sessions on bias. But it actually comes from the 1970s. Harvard psychologist Chester M. Pierce coined “racial microaggressions” then to describe conscious or unconscious attacks on Black people by non-Black people.

Pierce created the term after observing subtly racist commercials on broadcast television at that time. A later 1978 study by Pierce reported that Black people were almost always portrayed in subservient roles in ads, often working for or serving others, while white actors were almost always shown in positions of authority.

During the ’80s and ’90s, researchers broadened the definition to include attacks on anyone, regardless of race, typically in professional settings. (This is also around the time when companies began holding sensitivity training to address these kinds of remarks and actions.) Now the term has entered the zeitgeist once more, as Black Lives Matter has spurred discussion and adjustment (and more workplace training).

Black Americans, more than any other racial group, report experiencing the kinds of subtle attacks that have come to define microaggressions, and they can mean different things to different people. According to a recent Gallup poll, roughly one in five Black adult Americans reported frequently being treated with less respect and courtesy than other people—and 14 percent said they received worse service at restaurants and stores “very often.” Another 25 percent said they were “very often” treated as though they weren’t smart. Black men surveyed were more than twice as likely as Black women to say that people frequently acted afraid of them.

And microaggressions can happen to anyone: women, parents, the LGBTQ community, the young, the old. Male employees talk over a female colleague trying to get a word in at a meeting. Management questions a parent for having to pick up their kids from daycare. Gen Zers lob “Okay, boomer”s, and boomers blanket millennials as “entitled,” while Gen Xers are largely forgotten in generational conversations. The effect of microaggressions over a lifetime can be mental, emotional, and physical damage, says Tenniel Rock, the founder and clinical supervisor of the Centre for Anti-Oppressive Communication.

“When someone keeps shoving a message in your face or treating you in a certain way, part of you begins to believe it,” she says. “It impacts how you feel and what you do, but you’re not even aware of its root. And they [can] happen on such a regular basis. It’s daily, it’s on the way to work, it’s at work, it’s on the weekend.”

Science has studied the very real health problems associated with microaggressions. People who experience perceived racism may be at greater risk of heightened stress, which can lead to depression, cardiovascular disease, and other complications. What’s more, a 2019 study in PLOS ONE found that among Black and Latino people, many reported feeling that their doctors held negative stereotypes about their race, and that this feeling, encouraged by microaggressions (such as purposely avoiding discussions of diversity) from those doctors, may result in more stress, which in turn can cause anxiety and depression.

That’s why, Rock says, people who suffer from microaggressions can feel isolated: “You tend to blame yourself.”

MATT LORSCHEIDER, a career counselor at the University of Southern California, has worked with a number of veterans who’ve struggled with microaggressions, including some who’ve experienced impostor syndrome—the feeling that they’re frauds. He says that veterans tend to feel this way after returning to their civilian life. (It was once estimated that up to 82 percent of people experience impostor syndrome at some point in their lifetime.)

“Society tells us that we should have thick skin, words should never hurt us, and that if we are ‘disrespected,’ the appropriate solution is anger,” he says, "The rules of a civil society and of almost every modern work-place tell us that the latter will get us fired and potentially incarcerated—so we suppress our emotions."

For men, a stigma surrounding conversations about their mental health and treatment persists. And for many men of color, that stigma might be dramatically worse because of a lack of diversity in health care. A 2018 study estimated that between 56 and 74 percent of American Black men who have experienced trauma in their lifetime have had an unmet need for mental health services, making the lack of diverse representation a pervasive issue.

HAVING MOVED from Chicago to Los Angeles, Smith continues to grow in his craft as a filmmaker. He acknowledges that microaggressions will remain part of his life—but also that having conversations about them might help combat the issue. “I’m angry now because I wish I did something then, but you live and you learn,” he says. “I have a lot of non-Black friends, and I’ve even had to check them a few times. They consider themselves allies but talk about me as their ‘Black friend.’ If you want to improve things, stop calling me your Black friend. I’m your friend. This is not a seasonal trend. Black people go through this every day.”

Lately, while scrolling through social media feeds, Smith has found some messages of Black allyship triggering. When a former employer of his posted a Facebook message in support of Black Lives Matter, he was reminded of a time when he questioned the diversity of the company to his manager. (At the time, his manager responded by saying Black employees didn’t work out because they were “lazy.”) Enraged by the post and its performative allyship, Smith wrote a scathing reply, saying that if the company truly wanted to do better, it could start by apologizing to its Black employees.

“I’m sure they saw it,” says Smith. “They didn’t respond.”

You Might Also Like