Mickey Drexler on Leadership, Vision and Himself

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Millard “Mickey” Drexler is working through the notion of being recognized by the fashion industry as a visionary.

“You know, I was thinking about it. I always think when I am on SoulCycle. I really don’t know what a visionary is. I never knew I was one. It’s very hard to define. There is a feeling people have. You see around corners. You have an instinct. You get ideas anywhere and everywhere. I learned every day. I’m a student. No matter what we do, there are visionary opportunities,” said Drexler.

More from WWD

“Look, I really live in my imagination. I lived in my imagination since when I was young. I used to try to escape from my life. Ironically, that helped me develop more of an imagination, maybe. I have a constant imagination connected to businesses.”

On Wednesday, Drexler will be honored with the Accessories Council’s Visionary Award at the ACE Awards, the trade organization’s annual gala celebrating excellence in accessories and retail. Awards are also being given to Von Maur, Wolverine, Alexis Battar, Dee Ocleppo, Echo New York, Fashionphile, House of LR&C, Judith Leiber Couture, and Julianne Hough.

“I am honored and proud to receive the award and frankly, I love the recognition,” Drexler said.

For his acceptance speech, he’s got only a minute and a half. “I’ve never done a minute and a half. I often go on a tangent.” He’ll be sure to mention his wife Peggy, his confidante, adviser, an accomplished psychologist and documentary film producer who supported him through his career.

On a recent morning, Drexler entered Alex Mill headquarters, a modest, 6,000-square-foot site on Lafayette Street in SoHo with 23 workers. It’s a small company where Drexler typically works across a table from his son Alex, founder of Alex Mill, and creative director Somsack Sikhounmuong, among others, examining all the items. It’s not like J. Crew Group, where Drexler used a megahorn for announcements, and a bicycle to call upon someone.

Though the interview topic for the day is on visionary stuff, the always outspoken and opinionated Drexler unloads on corporate bureaucracies, department stores where he never saw a future for himself, and certain individuals in high positions that he worked for, but prefers to keep most of that private. He talks about having a difficult childhood and being shy till attending college. “I certainly was not of the manor born. I came from a ground floor apartment in the Bronx, one bedroom. I didn’t want to be there.”

His mother was diagnosed with cancer when he was just a toddler. She passed away when he was a teenager. It was his three aunts (his mother’s sisters) who also lived in the Bronx that he turned to every day. He said he had no relationship with his father, who worked in the shipping room of a coat company. “He wanted to be a big shot. He dressed very well, but he was making less money than almost anyone in the shipping room.”

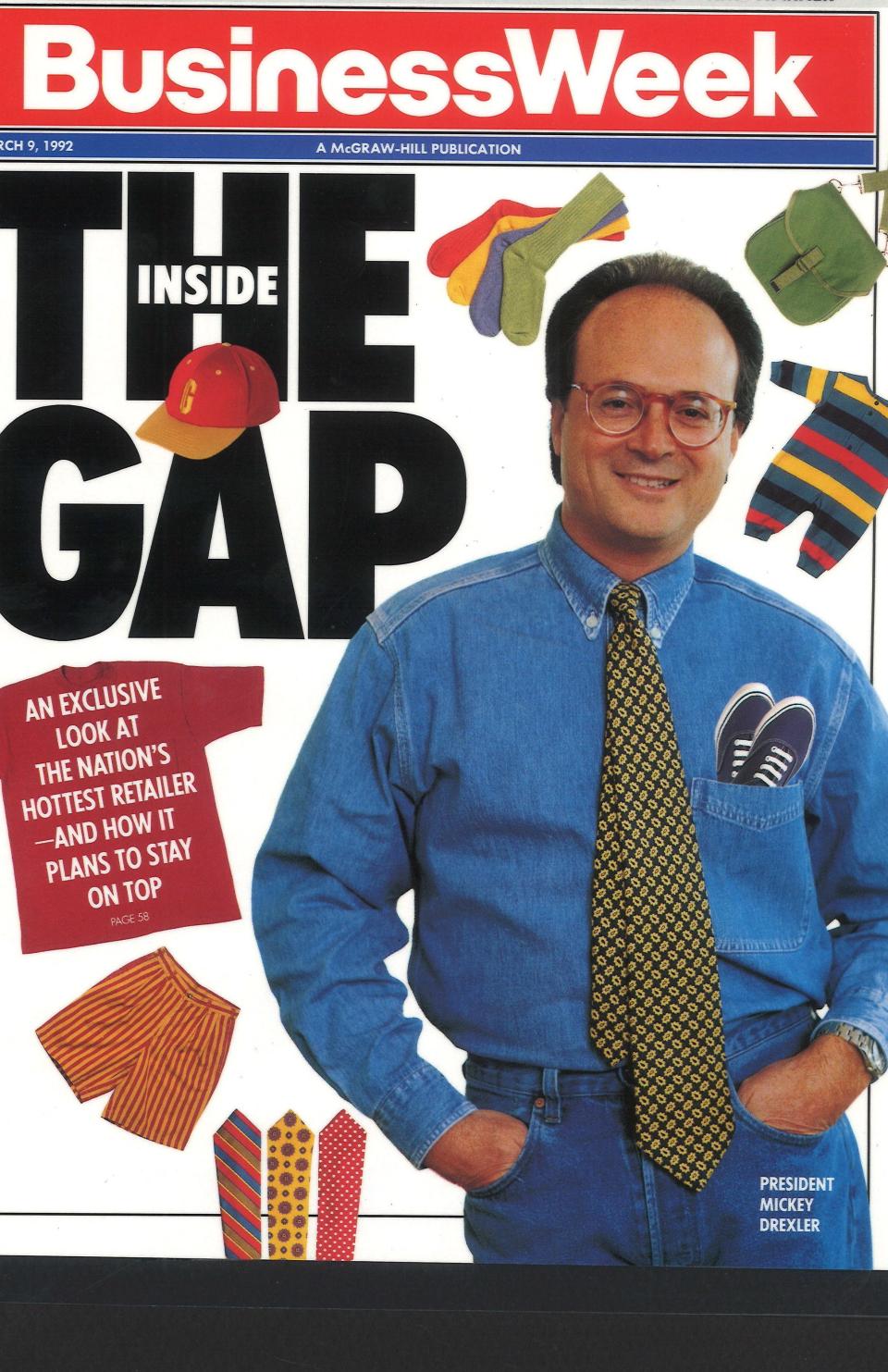

During the course of his career, starting as a trainee at Abraham & Straus, holding buying positions at Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s, and rising to chief executive officer of Ann Taylor, Gap Inc., J. Crew Group, and currently Alex Mill, he was inspired by many who have long passed, including Katy Murphy, a Bloomingdale’s fashion director; longtime Gap consultant Rose Wells, and Steve Jobs, among others. While revered for his work in reviving Ann Taylor in the early ’80s, catapulting the Gap in the ’80s and ’90s and J. Crew in the 2000s, and successfully launching Old Navy and Madewell, he admits to mistakes, like launching Hemisphere, a short-lived retail concept at Gap Inc., inspired by the luxury store of the same name in Paris.

Getting fired at Gap by Don Fisher, the late founder and chairman of Gap Inc. who recruited him from Ann Taylor, has become part of retail lore, though Drexler has argued that the Gap turnaround strategies he implemented took root after he unceremoniously left the business. Drexler also left J. Crew when the company hit a low, though the brand grew enormously in size and popularity during his tenure.

“I always think I picked the goods pretty well,” said Drexler. “Of course, you’ve got to make mistakes. Mistakes are mandatory.” It’s his opinion that with growing a company or starting one, mistakes just come with the territory.

“By the way, people say I’m a micromanager. I’m not. I represent the customers. I’d like to see more micromanagers around who care about customers. It’s the details. Somebody has to care about that.”

Thoughts on leadership and vision start to click in. “You can’t be an imperial leader in a tower. You must be among the team members letting them know you are approachable, friendly, demanding. Too many leaders spend more time criticizing or looking for opportunities than praising people. I have had that disease a bit. People also need empathy and sensitivity. I always try to be their partner in an organization, but also very tough and with high standards. I was always available.”

And then there were those who second-guessed him. “When I made the move to Ann Taylor I got nothing but negatives from people I knew. ‘What are you doing that for?’ they said. I did it because I wanted out of what I was doing,” which was working at department stores. Too bureaucratic for him.

Ann Taylor marked his first CEO job. “It was a good opportunity to learn how to run a business,” said Drexler. “The vision was fair pricing, very tasteful. It’s always taste and style. My muse was Jackie Kennedy. I didn’t know her but I sent her every catalogue,” even if she didn’t ever place an order. “If I can satisfy Jackie Kennedy with Ann Taylor, who knows? I always reached high, personally and professionally.”

Four years later, he joined Gap Inc. “Again, it was like, why are you doing this? It was kind of the standard response” to his career moves.

Fisher initially wanted Drexler to do a start-up. But Drexler told him, “I would be worried about you funding a new business when your main business is not very healthy at all…The stores were horrible. We redid all 450 Gap stores. Everything was promotional. Everything was named differently. We redid the goods. We threw out the crap. Levi’s was all discounted. And I threw all that out. I started washed Levi’s at $35 instead of two for $26. I had this fire in my belly. I was very anti-authority growing up. I didn’t want to have someone bossing me around.”

Regarding Fisher, “We were opposites, but that was a key reason that our partnership worked. We could not have done this individually. We fed off each other’s strengths.”

So what was Drexler’s vision for Gap, where he served as president and also CEO? “Back when I was at A&S, I had a vision for a company, a dream. I made up a list that I put in a drawer that really described what I would later do at Gap — colors, fleece, T-shirts, style, casual and, personally, I wanted nice cool clothes that I could afford. I didn’t know this would be my future. I don’t know why I made that list up. I didn’t see anyone out there doing that, maybe Benetton, which I thought was very cool. I pictured what appealed to me about clothes and about the consumer. I admired Ralph Lauren. He always had great taste and style, but I thought his clothes were too high-priced, certainly for me. I thought the marketplace could use cool, stylish clothes, something casual that was reachable by a big audience. I imagined it in my mind. I had this vision of color, which I always thought about. Color was always the first appeal to merchandising a store.”

In 1994, Drexler launched Old Navy, which became the cash cow for Gap Inc. “My imagination was sparked by an article. I used to read the newspapers and business sections more than I do today for obvious reasons. The article was buried in the business section of The New York Times, on Target, then known as Dayton Hudson, starting a company that would be a less expensive version of Gap. It was called Everyday Hero. In those days Gap was on fire. I went to visit the store, in the Mall of America, as soon as it opened because only the paranoid survive, as Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, mentioned many years ago. A really smart guy. [Grove died in 2016.] I walked out of the store probably in three minutes, kind of relieved. This was so not Gap at lower prices. In a restaurant or in a store, you feel an energy or you don’t. You feel a vibe or you don’t.”

Drexler then visited two Gap stores in the Chicago area and learned from those store teams that people thought Gap’s prices were too high.

“That blew me away.”

Soon after, Drexler did some homework and learned that 80 percent of the jeans in America were sold for $30 or less, while Gap jeans started at $34.50.

“I was kind of stunned. Twenty-five to 30 percent of our business was denim.”

Back at the Gap’s San Francisco headquarters, Drexler gave 10 employees $200 each, and told them to shop a particular category at a discounter, be it Kmart, Walmart, Sears, Target, or Mervyn’s, which is no longer in business.

“A week later we met to hear what they thought about the stores. It was music to my ears. They liked fashion. They didn’t care about sales, if the value was there. They liked clean stores, fashion or nice merchandise, and some service, and that convinced me to launch Old Navy. I named it after a bar on Rue St. Germain in Paris I spotted while on my way to the airport. I never went into it. I wish I had. And I loved the name for any business. I checked the next day to see if that name was usable. The good news, it was. The board did not like the name. We hired two naming companies [agencies] at $2 million or $1 million, which were beyond the worst. One came up with the name ‘elevator,’ another, ‘forklift.’ it was unbelievable. But you know, when you don’t get it, you don’t get it.”

Eventually, Drexler got one of the agencies to come up with the name Blue Indigo, which Drexler knew was trademarked. Instead, the prototype opened was called Gap, on top, and underneath Old Navy. “I said if we use that name, Gap will not be in business five years from now.” Not long after, the Old Navy name was adopted.

The origins of Madewell go back to 2003, when David Mullen, a wash specialist who consulted at Gap and was founder of contemporary sportswear brand Save Khaki United, showed Drexler a logo of a defunct workwear company in Bedford, Massachusetts, called Madewell.

“I bought the name and tucked it away,” Drexler recalled. “I always loved the vibe of workwear. Carhartt, Dickies. It was a thing.”

A year later, Drexler, sharing talent from J. Crew, launched Madewell. “The imagination started with the name. The thought was to have a jeans company. Gap had a big jeans businesses, so did Old Navy. We felt jeans would be the base.”

Further inspiration came from the Vesuvio bakery on Prince Street in SoHo. “I loved the store front. The color. It’s authentic. It’s a great old vintage bakery. We didn’t copy it exactly; it inspired the design of the Madewell store. I never went inside. Sometimes you can tell a book by its cover.”

Madewell was Drexler’s last start-up, but his track record of launching and building businesses begs the question of whether there’s another one in his future. The imagination keeps going. He embraces challenges and seems to crave the action.

“I will always have thoughts and ideas about a new business. But there’s a relaunch of Alex Mill going on and it’s in its fledgling stages, and building any business and managing it is always a long-term commitment,” said Drexler. “That doesn’t mean I will not imagine or fantasize about a new business. I can’t help myself.”

Mickey’s Musings

On growing up: “I didn’t know we weren’t well-off. Who knows that kind of thing? Because everyone I knew was not well-off in the Bronx until I met my rich friends at Bronx High School of Science.”

On his father: “We didn’t have much of a relationship. In a way, he was a tragic, bitter, angry man because he wanted to be a successful person, and he wasn’t. A lot of that rubbed off.”

On taking risks: “There’s no such thing as not taking a risk. No risk, no rewards. As I’d say to the team, we have made mistakes, we’ll make more. But I learn from each of them. Of course, I wasn’t happy after we opened Hemisphere, which was a very upscale, multibranded store. I happened to love Hemisphere in Paris. We took the name. I was very emotional about it. It failed. We wrote it off. I never look back but I worried a lot about success. I do believe we all have a fear of failing but it’s necessary to take risks to build any organization.”

On imagination and taste: “I take pictures in my mind. I don’t know why. I have this instinct, and good taste. They said I was the best-dressed guy in grade school. They didn’t know how to explain it. But I knew why. It was what I wore every day — an H.I.S. buckle-back chinos with high-top Keds.”

On hiring: “When I interview people, I don’t really care where one went to college, I don’t care about what their grades were or their board scores. I care who they are, what their growing up years were like, if I feel there is fire in their belly and that they are nice. I learned that from the streets. I think a lot of what people are competent at is related to DNA, especially in the art fields. In any field, you’ve got to be creative…Evaluating merchandising or styles or fashion is not something you can learn, a lot of it is about instinct, style, gut, etc.”

On collaborations: “Right now it’s been overdone in the industry. When we did it at J. Crew I thought we were inventive. We did it well. Of course you make mistakes. Now we only do very unique, special, scarce collaborations at Alex Mill.”

On research: “I always do my own research, in a dramatically different way,” from conventional methods. “I don’t hire agencies. I go to stores and ask people about companies; they tell you everything. I am a student every day. When Gap was having a bad year, the board wanted a focus group, but after 10 minutes, you see that focus groups are not looking forward, they’re looking current and rear view mirror. They get paid to be there.”

On visionaries: “I’d like to single out some people you might not expect me to single out. Eva Moskowitz, founder and CEO of the Success Academy Charter Schools, is a hero. She created something, had a mission, and has contributed enormously to education reform. And Wendy Kopp. She’s the CEO and cofounder of Teach For All, which has organizations in different countries working to expand educational opportunity. She’s also the founder of Teach For America,” a national teaching corps. “These are two women who have made a difference in the lives of thousands of children and will continue to do so.

“I have to also cite Steve Jobs, a visionary, needless to say. He’d be on anyone’s list of visionaries. He changed the world and we feel it every day. But I also personally thank Steve for our 16-year friendship and how he influenced me, through his willingness to always take creative risks, which is necessary to grow or build any organization or business. One can only imagine what more he would have accomplished but sadly we lost him way too early.”

Best of WWD