Michael Mann's First Great Biopic Found the Michael Mann Man in Muhammad Ali

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

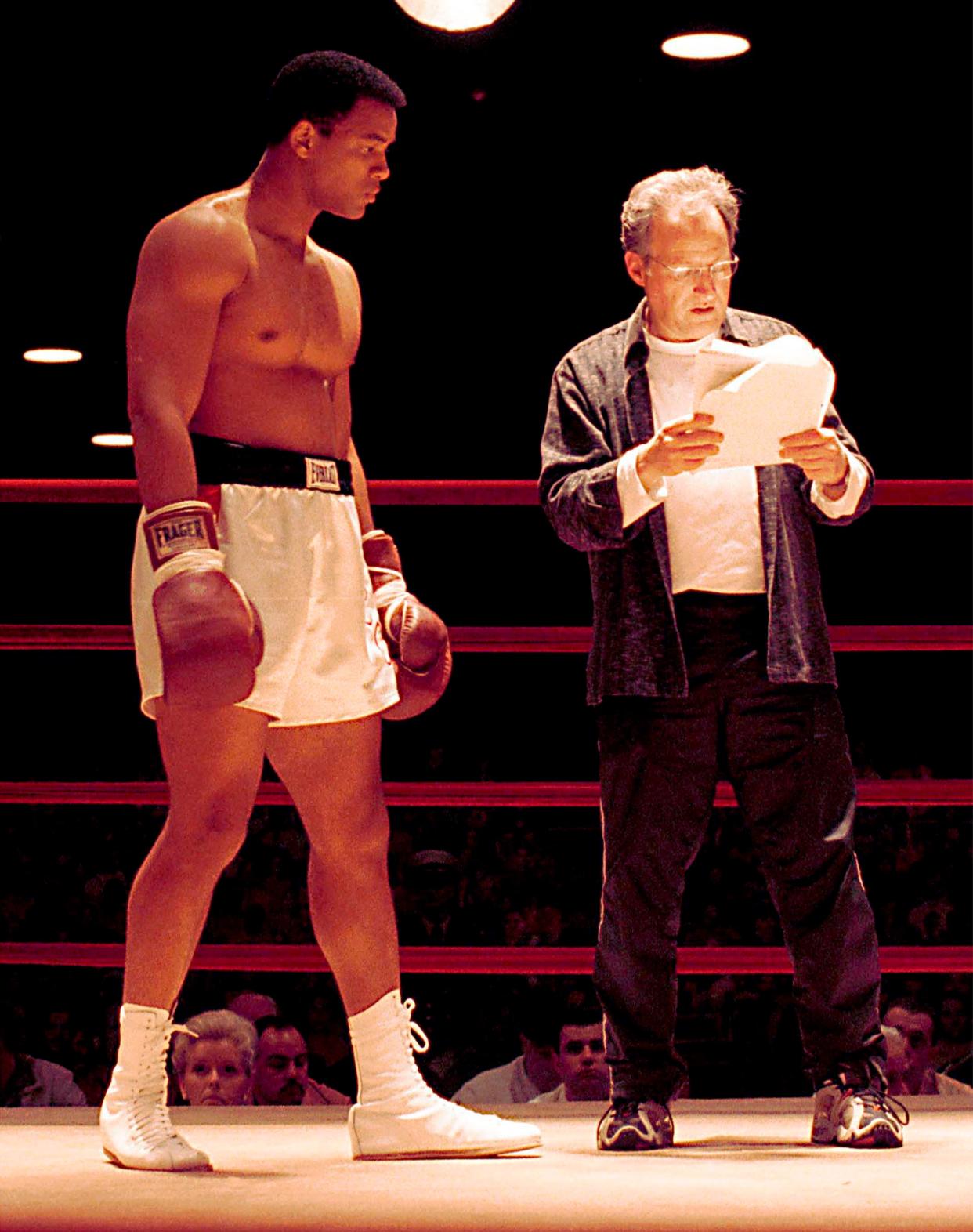

Peter Brandt/Getty Images

In the fall of 1974, in Kinshasa, the capital city of a country then known as Zaire, the thesaurus-fed boxing promoter/folkloric raconteur Don King, sat in a hotel room next to James Brown. King, draped in a Dashiki and crowned with his trademark shock of picked-out Super Saiyan Afro, was addressing a documentary film crew about a fight he had organized, or conjured out of thin air, between Muhammad Ali, the exiled former heavyweight champion of the world, and the young indomitable belt-warmer he was challenging, George Foreman, a soft-spoken hulk from Texas with a wrecking ball for a right hand.

King said, of Black athletes and entertainers in America, “We’re only useful as long as we’re necessary. So when we become unnecessary, then we’re no longer useful, and they don’t realize your strength comes from your community, and you have to deal from your strength because in dealing from your strength you got somebody.…..But when you’re dealing as an individual, no matter how big you get as an an individual, if you’re Black you still a n*gger....And when you stand there by yourself, you’re all alone.”

This idea is at the heart of Michael Mann’s 2001 biopic Ali, a muted, transcendentalist two-and-a-half-hour boxing film without a ton of boxing, made by a then-58-year-old white Chicagoan, about one young fighter’s search for Black community and self-realization during the Civil Rights Movement. The film showcases Mann’s unorthodox approach to the biopic, a genre he’s returning to with this year’s Ferrari. He’s less interested in hitting all the milestones and the beats, then in using the lives of his subjects as parables. He ducks and weaves to draw out aspects of history, of society, of life, that Ali, or Enzo Ferrari, or Lowell Bergman help us understand.

Don King was addressing the director Leon’s Gast’s film crew for what was supposed to be a concert film and instead, after a 22-year journey, became 1996’s Muhammad Ali: When We Were Kings, a near-perfect, Oscar-winning documentary that—along with Ali’s lighting of the Olympic flame in Atlanta the same year, and a subsequent, masterful book from future New Yorker editor David Remnick (King of the World, 1998)—fueled a renewed wave of interest in Ali. Mann’s film dropped at the tail end of this wave, and may have suffered for that. Many critics felt, and still feel, that Gast’s documentary made Mann’s film look like a pale historical reenactment, derivative and irrelevant compared to the “real thing”.

But the film’s value is in the looser approach it takes to adapting its subject’s life. It focuses on a pivotal 10-year period that represented the summation of Ali’s life’s work to that point and would color everything that followed. It opens in 1964 with the fight that birthed Ali’s legend—when, as a garrulous, shit-talking 22-year-old sideshow, who dropped his hands and danced and didn’t fight how heavyweights were supposed to fight, he usurped Sonny Liston and stole his Heavyweight Championship belt. It ends in 1974, in Zaire with the Foreman fight that cemented Ali’s legend, when the 32-year-old elder statesman defied all odds and shocked the world by winning the belt back.

Ali has a wider scope than both Remnick’s book (which focuses on the fighter’s first few years leading up to his abstention from military service, and can be read as an urtext for the film’s first act) and Gast’s documentary (which informs the third.) Mann uses the interim of those ten years to selectively address the chaos and confusion of the Civil Rights era. It's a biography rendered as poetry, more indebted to Malick and Stone than Barry Levinson, and one that is meticulously researched, but doesn’t need to show its work. Gorgeously shot by Emmanuel Luzbeki, with star Will Smith supported by an incredible ensemble of great character actors, it screens just fine as a popcorn entertainment, but the numerous Easter eggs and uncredited representations that fans and historians will recognize explain what it was Mann was actually up to.

The film was a deeply personal effort and a huge risk for both Smith, who was portraying a living legend, and Mann, who was coming off a ‘90s hot streak critically and commercially, culminating in this blank-check passion project. Mann is a year younger than Ali, and had always thought of him as an avatar for their generation. He had a feeling of kinship, rooted in shared counter-cultural experience as well as a shared rage and sense of injustice. Mann took pains to get as close to the story of the film as possible. The director met with Ali in person several times in the leadup to the film; Ali was consulted on journalist-turned-screenwriter Gregory Allen Howard’s story and the screenplay, credited to Mann, Eric Roth, Stephen J. Rivelle, and Christopher Wilkinson. When the film went over budget, both Mann and Smith came out of pocket for financing. Smith’s then-wife, Jada Pinkett, played Ali’s first wife, Sonji Roi. Ali’s lifetime friend and photographer Howard Bingham (portrayed in the film by Jeffrey Wright) was brought in as a producer on the film. Ali’s trainer Angelo Dundee (Ron Silver) was a fight consultant, and sat in on Smith’s training sessions (9-10 months of preparation, according to Mann).

Through the 90s, Smith had made a series of leaps— from family-friendly rapper to sitcom star to full-blown box office phenomenon. Prestige, auteurist projects were the inevitable and logical conclusion, and Smith committed fully, studying an Ali curriculum Mann devised for him. He underwent the time-honored Oscar-hopeful ritual of bodily transformation, putting on 35 pounds of muscle (to match the similarly-built Ali’s fight weight against Liston, 210 pounds) and nailing his Ali impression, from the champ’s overhand right to musical speech pattern, capturing the fighter’s essence while resisting parody. There was an attempt, at first, to simulate the painstakingly reenacted fights blow by blow, but eventually Smith and Mann agreed he’d simply have to become a credible boxer in a matter of months, a process that included learning to take the occasional punch.

Ultimately, what makes the movie—and Smith’s performance—extraordinary aren’t the moments that are re-enacted from footage in the ring or from weigh-ins or pressers. It’s the imagined off-camera moments, where Ali is taciturn, full of doubt and frustration, looking for a way to stay true to himself and his beliefs while pursuing his craft, that really help us understand the winking and performative nature of “Ali”, the on-camera showman. Ali makes for a classic Mann protagonist. He’s a lone, brooding hero, attempting to navigate hostile institutions of authority, armed with his own philosophy and code of ethics. Like all of Michael Mann’s difficult men, what Ali truly craves is basic personhood, and complete control over his career and life; independence from his father and his father’s Christianity, from the American white power structure, from mob control of his sport, from hucksters like Don King, and eventually, from the Nation of Islam. The film is a cataloging of how far Ali has to go, how much of himself he’s forced to sacrifice, to ultimately earn that freedom. As Drew Bundini Brown (an atomic Jamie Foxx), Ali’s shamanic cornerman/poet laureate tells the fighter, who in the moment is broke and suffering due to his costly pacifist protest of the Vietnam War, “Free ain’t easy. Free is real. And real is a motherfucker. It eats raw meat, and walks in its own shoes. It don’t ever waver.”

Ali’s dilemma at the time, and in the film, is that there was no role in public life for a Black iconoclast to fill, no common language for society to understand him. He’s not a Phillip A. Randolph type trading in respectability politics, an institutionally-approved “credit to his race” Black champ like Joe Louis or Floyd Patterson. Nor was he a silent “glowering menace” like Sonny Liston. Ali was beamed in from the future, a confident middle-class product of a working two-parent home excelling in a sport historically dominated by the poor and desperate, a perfect spectacle of warmth and anger, winking humor and searing political critique, a clown with unimpeachable dignity who was totally in on the bit, a seer with an innate understanding of where politics, culture, and life were headed, and—by the way—also one of the all-time athletes in any sport.

The film begins with what could qualify as one of the great music videos and/or short films ever made, a montage that contains all the film’s core themes, soundtracked by Ali’s friend Sam Cooke running through a 10-minute medley from his Harlem Square performance in 1963. As Cooke grabs his dick, horrifying parents and mesmerizing their kids, he’s not unlike Ali, suggesting a new consciousness is emerging, that a new type of brash, unapologetic Black celebrity is being born in cramped clubs and boxing rings across the country.

The first official line of dialogue in the film is delivered in Miami, the night before the first Liston fight, by a white a cop in a patrol car, caught on Mann’s beloved, grainy, turn of the century digital, asking the fighter then named after a white farmer and abolitionist: “What you running from, son?” And then Mann shows us the answer— a history of traumatic racist experiences through Ali’s young life as a Black kid in the segregationist South, where lynchings like similarly-aged Emmet Till’s are quite literally thrust in his face, along with images of a white Christ. These are drawn by Ali’s father (Giancarlo Esposito), who made money as an artist painting signs, with a side gig/passion for producing devotional murals. There’s also a brief scene of Cassius Clay Sr. launching his son’s professional boxing career by signing him to a contract with an all-white syndicate of local old money industry barons known as the Louisville Sponsoring Group. We cut to a dejected, skeptical Ali, sitting in the foreground, a table of ruddy suits grinning around him, framed by a mahogany wall lined with photographs of race horses.

We meet Ali’s team. The aforementioned Dundee, Bundini, and the doggedly loyal, stuttering Bingham. It’s instructive to consider why these men ended up being the family Ali chose for himself. What Ali desired were people that would allow him to be himself, to say what he wanted to say, to train how he wanted to train, to fight who, how and where he wanted. His bond with Angelo Dundee was built on a foundation of mutual trust and respect, but most of all on the uncommon deferential autonomy the trainer would grant his fighter. Dundee said, “You couldn’t actually direct him to do something…. He resented direct orders. He wanted to feel that he was always the innovator, and so I encouraged that.” In other words, Angie didn’t try to train or teach Ali, but to hone him. His corner was the only place Muhammad would find the non-judgemental, unconditional support he spent his career in search of. As the team in Mann’s film coalesces around Ali in the gym, it has the feel of a heist movie, getting a crew together for a big job, and essentially that’s what it is. Collectively, these men will soon take over a sport, a country, and the world.

He also attends a Malcolm X speech (Mario Van Peebles, doing arguably the second best characterization we’ve seen on film). Malcolm’s speech centers on self-reliance and self-determination and echoes Marcus Garvey’s separatism, which Ali’s father espoused at the dinner table throughout his childhood. In it, and in the message of Elijah Muhammad, Ali hears an alternative to the empty pacification of Christianity, the martyrdom of the civil rights movement, and the calculation of fighters who took dives and beatings hoping whites would pity them. The strength of the Nation, their Booker T. Washington-cribbed dignity—the discipline and comportment Ali wasn’t allowed under Kentucky’s apartheid rule—spoke to him. Elijah Muhammad wove these threads of Black philosophy into a marketable mythology he could use to impose his will on lost, angry young Black people, and would become Ali’s de facto father figure.

Immediately following the Liston upset, with Malcolm X in tow on the street in New York, Mann shows us Ali’s dramatic reveal: He comes out publicly as a Black Muslim and a disciple of the Nation of Islam, and that going forward, his slave name was dead. He’d be referred to as Cassius X. This had been a subplot in the press leading up to the fight, but the time it was still a shock, a controversy, and a tremendous sacrifice. Even before he refused his draft orders, Ali’s ties to the Nation would confuse, scare and piss off the great majority of white America (and media) for years. Here was the heavyweight champ, at a time when boxing was at the center of American life, aligning himself with a radical Black religious faction. But the film explains that the Nation gave Ali a narrative, a greater purpose that extended beyond his work as an athlete/entertainer, one that matched his contrarian taste for defiance and provocation. As he says to a crowd of fans and reporters in Harlem who asks if he’s going to be a champ like Joe Louis, “I’m definitely going to be the people’s champion. But I just ain’t gonna be the champ the way you want me to be the champ. I’m gonna be the champ the way I wanna be the champ.”

The middle portion of the film focuses on two relationships—and two betrayals Ali is forced to make—that explains why his connection to the hypocritical Black power institution was ultimately doomed. It’s here that the film reveals its genius. Most cinematic depictions of the Civil Rights Movement through the ‘90s didn’t hold back on white Southern evil and the government’s complicity in the terror and violence that Civil Rights marchers faced, but were mostly black-and-white in their morality, largely depicting the movement and its leaders as a united front led by assured, mythic visionaries. In Ali’s entanglement with the Nation—who took over his management, his security, his social calendar, and his love life—we see him trading the domineering hand of his father and the Louisville Sponsoring Group for an equally if not more oppressive and exploitative force. But the film goes to lengths to explain how America created the conditions that would make the appeal of the Nation of Islam’s message so persuasive to Ali and many others in the first place.

The ensuing Malcolm/Ali rift shows how difficult it could be during this era to navigate the blurred lines of race, to separate freedom fighters from thieves, prophets from dictators, friends from enemies. This is how Ali makes the decision to side with the security of the Nation over Malcolm, his big brother figure turned the fallen minister, as depicted in agonizing real time in the film. At Mann’s meetings with Ali, in which he spoke candidly about mistakes he’d made and regretted, he said turning his back on Malcolm X was the greatest.

It’s the same for Sonji Roi, who by all accounts Ali loved deeply, but couldn’t tolerate due to her resistance to the Nation’s orthodox standards of comportment and dress. The Nation was quoted directly in their divorce proceedings. His last words in the film to Sonja are “How I am says something,” an acknowledgment of Ali’s constant awareness of the stakes of his public life—as a public figure representing both the Nation and Black people as a monolith, and as a myth and legend being written and recorded— and the sacrifices he felt he had to make in the interest of presentation. As an epilogue to the relationship, Mann shows him kneeling at the foot of their bed, in a kind of prayer stance over one of Roi’s discarded, forbidden slinky dresses.

One of Elijah Muhammad’s legendary acts was refusing to register for the draft in WWII; he would later be charged with sedition for instructing his followers not to register for the draft or serve in the army. This had to be a factor in Ali’s fateful decision to claim exempt status when called to serve in Vietnam, even when presented with alternatives that would’ve allowed both the fighter and the government to save face. The film depicts the fateful day—April 28th, 1967—when Ali sacrifices his passport, an estimated eight figures in purses and endorsements, his championship belt, and three and a half priceless years of his prime. It’s still one of the most pure, bold, consequential acts of individual protest in American history.

In Ali we see one of the most outspoken and independent Black leaders of his era or any other falter and make “the wrong choice” by siding with the Nation several times, and staying loyal to them far longer than they were to him. During his suspension, when he was of little use to them, Elijah Muhammad turned on Ali, like he did with Malcolm, because he spoke out about his finances. He was broke, and the Nation wasn’t supporting him. He was reinstated when he proved himself an earner again, but never forgot the slight, nor did he quite have the strength to fully extricate himself from the Nation’s management and security during that period of his career. The film’s most brutal passage contains no fighting. After beating Jerry Quarry, setting up the fight Joe Frazier agreed to in an act of uncommon generosity and compassion, Ali wilts, allowing his manager, Elijah Muhammad’s son Herbert Muhammad (Barry Shabaka Henley) to make the deal, as his second wife Khalilah (Nona Gaye)—who saw Elijah Muhammad for the usurious, monorail salesman he could be—looks on in horror.

Ali was never the same after his exile. He had lost a step, perhaps even two. His two fights preceding Zaire were the resulting 15-round marathon with Joe Frazier he lost by unanimous decision, followed by a slugfest with Ken Norton in which his jaw was broken. Foreman was eight years younger, had knocked out Norton in 36 seconds, and knocked down Frazier six times, demolishing him and taking his belt by force. He was generally thought of as an indestructible golem no man could last more than three rounds with. The odds were 4-1 against Ali coming into the fight, and this was only because he remained so beloved—they should’ve been far worse. Many genuinely feared for his health and safety in the ring. In the film, everyone doubts Ali going into the fight: Khaliliah, Don King, Howard Cosell. Even during the fight, Angie and Bundini, who were literally in his corner watching up close, couldn’t understand why their fighter was insisting on throwing out their script for the fight and leaning back on the ropes as it appeared he was getting pummeled.

When Ali refused to serve under the U.S. military, the British pacifist Bertrand Russell immediately understood the importance of the act, writing him at the time: “You are a symbol of a force they are unable to destroy, namely, the aroused consciousness of a whole people determined no longer to be butchered and debased with fear and oppression.” From the moment he gets off the plane in Africa, as Mann lingers on Ali running in the streets of Kinshasa with a mob of supporters around him, this is made flesh. He is overwhelmed by the love and support of a country, a continent united behind him, finally seeing the true impact of all his protest and sacrifice. We see graffiti of Ali fighting tanks and planes and a white man in a suit, a symbol of Black resistance to the American military complex, to racialized oppression and imperialism. The global impact dawns on Ali, that he is “The People’s Champ” in a way even he may not have ever fully comprehended. In voiceover, Ali says to himself, “You face a man who will die before he lets you win.” It’s Ali digesting that he has surpassed his sport, his country, and become a godhead. He realizes for the first time, losing isn’t an option. Winning means too much, not just to him, but the people who love and believe in him.

Of his film, Mann has said, “If there’s a theme of the movie, it’s defiance. That is why people identify with and worship Ali, because he represented the enormous possibility, the poetics of actual self-determination. He does it. We can do it. That’s what he stood for. To do that, he had to defy not just the establishment and not just white America and not just people who feared militancy, but also the NAACP, Joe Louis, you name it. Everybody who was centrist and had an interest in maintaining the status quo.” It’s the story of an individual who was trapped inside a mid-century American trash compactor of institutional rot, the fetid walls closing in on all sides, and escaped.

Long after the relative disappointing performance of Ali, the champion and his story stayed with both Michael Mann and Will Smith. The director released yet another cut of the film following the fighter’s death in June of 2016. And when Muhammad Ali was laid to rest in Louisville a week later, Will Smith served as a pallbearer.

The final shot in Ali is a freeze-frame reminiscent of Cassius Clay Sr. 's devotional murals. The fight ends, the ring fills with ecstatic disbelief, and the skies over Kinshasa open up. It’s as if the Gods themselves have been holding back the weather, refusing to interrupt a miracle. The reborn heavyweight champion is recalcitrant in victory. He first looks off Don King, making it clear this was a temporary marriage of convenience. His manager, Herbert Muhammad is nowhere to be found. The camera captures Ali standing on the bottom rope, above the fray in the ring and in the crowd, with his arms outstretched towards the rains and his adoring, beloved people. Huddled below the fighter are Howard, Angie and Bundini. And so Ali exits the film, and this incredible decade of a life, with the same core he entered it with. The film’s message is clear: If you are Black in America, greatness must come from within.

Originally Appeared on GQ