Michael Jackson: On the Wall, National Portrait Gallery, review: entrancing, bonkers, and sure to put a smile on your face

Nearly a decade on from his death, Michael Jackson remains a hugely controversial figure. For millions around the world he is an idol, the ultimate personification of glamour. For another, equally substantial constituency he’s far from heroic: a beautiful African-American man who – while protesting his black pride – denied his identity at every turn, becoming a grotesque, self-mutilated projection of American show-biz values at their most destructive. Not to mention the allegations of paedophilia that have trailed in his wake, and the abuse he himself is said to have suffered as a child.

None of which makes him an inappropriate subject for an exhibition. Quite the reverse. Jackson’s basket of tragic contradictions, not to mention the baroque kitsch of his public image – and, oh yeah, his music – are a gift for any artist. So it’s hardly surprising that he should have become, as this bold and enterprising show at the National Portrait Gallery puts it, “the most widely depicted cultural figure in contemporary art.”

This isn’t an exhibition about Jackson per se, or a celebration of his career in the manner of the V&A’s David Bowie and Pink Floyd blockbusters, for instance. Instead, it’s an exploration of Jackson’s “impact on contemporary art”; an opportunity to see what artists have done with his image – from precocious talent in the Jackson Five, to drug-addled quasi-suicide in middle age – and to see what that tells us about the state of art today.

The show starts spectacularly, with Jackson in his pomp: as renaissance potentate in a full-size equestrian portrait by Kehinde Wiley (best known for his Obama portrait), a pastiche of a Rubens painting of Philip II, commissioned by Jackson himself (without apparent irony), shortly before his death in 2009. He’s also pictured as a modern messiah in preposterous, eight-foot-high images by photographer David Lachapelle: a winged Jackson standing triumphantly on Satan; a dead Jackson cradled by a radiant Christ in a reconfiguration of the Pieta.

The feel of these, though, is more uber-camp album cover than contemporary spiritual masterpiece, and as you take in a wall-filling video of American artist Susan Smith-Pinelo’s cleavage bouncing in time to Jackson’s Workin’ Day and Night, then walk through a gateway formed from Mark Rydon’s phantasmagoric artwork for the Dangerous album, it’s as though you’ve entered some entrancingly bonkers fairground attraction – but one that hasn’t got quite as much to do with art as you’d expect or, certainly, hope.

While there’s no shortage of portraits by name artists, from the brilliant (Gary Hume’s circular image of pale skin and hypnotic eyes in household gloss) to the boring (Maggie Hambling, Keith Haring and Grayson Perry all disappoint) – few of them probe beyond the surface of the self-styled King of Pop.

South African Candice Breitz’s video installation King (A Portrait of Michael Jackson) showing 12 super-fans singing the whole of the Thriller album a cappella and alone then projected simultaneously, sounds madly kooky on paper, but because “re-performing” things has become such a familiar trope in art in recent years, the ultimate effect is rather tame.

There is truly astounding footage of Jackson’s 1992 Concert in Bucharest, Romania, an event seen as pivotal in the country’s embracing of capitalism, a “moment of mass hysteria” as Romanian artist Dan Mihaltianu resonantly puts it, “in which everyone from politicians to street children participated”. Yet the work Mihaltianu has created around it, juxtaposing masks of Jackson’s eyes given away at the concert with newspaper images of ordinary Romanians, is pretty dull.

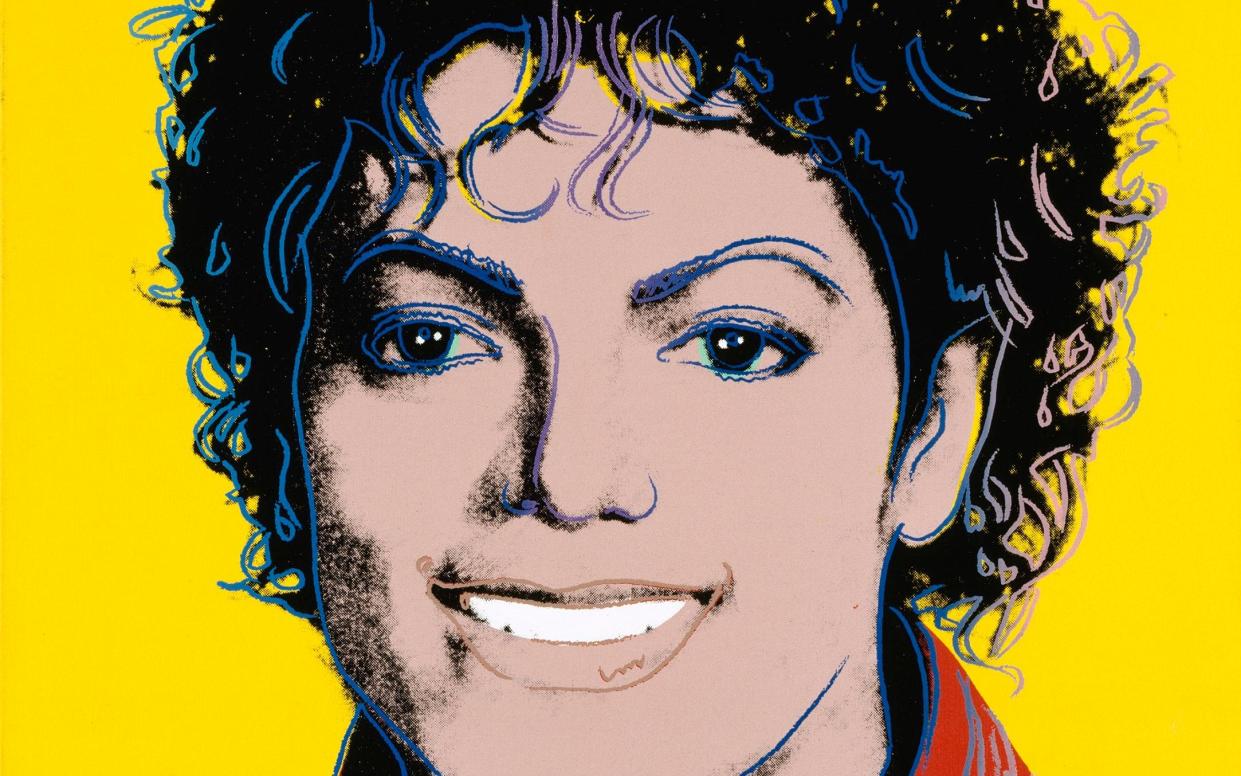

Andy Warhol, that great connoisseur of “iconic” fame, inevitably enters the fray, with informal black and white snaps of Jackson and his brothers blown up into atmospheric wallpaper, though his Michael Jackson, 1984, three identical images of the smiling young singer in three different colour-ways is late Warhol at his most blandly generic.

It’s with African-American artists, who have, perhaps, a stronger personal and cultural investment in Jackson’s story, that the exhibition starts to bite. Rashid Johnson’s The Wiz, for instance, a kind of altar to Jackson’s failed 1979 film tribute to the Wizard of Oz, formed from a mirrored shelving unit with LP records, spattered with shea butter, black soap and other African-American cosmetic products, gives a visceral sense of Jackson as a constant, gnawing, almost biological presence in black life.

Even closer to the bone, Hank Willis Thomas’s Time Can Be a Villain or a Friend, 2009, is simply an enlarged 1984 image from the African-American lifestyle magazine Ebony, showing an imagined projection of how Jackson might look in the year 2000. This suave, moustachioed soul-man could hardly make a more poignant contrast with how Jackson would actually look, when he’d become, as Willis puts it, “a monster of all of our perversions projected onto him.”

Most telling of all is a series of student collages from 1984, by British artist Isaac Julien: assemblages of tabloid newspaper cuttings designed to critique the way this great black figure was perceived by the British media. In fact, a Sun article entitled “The superstar who never grew up”, presented in its entirety, is one of the few artefacts here that really illuminates Jackson’s tragedy, as the singer talks about how he only feels safe on stage: “I’d sleep there if I could” – the utterances of a man who remained, until the end, a prisoner of his brutalised childhood.

You don’t, of course, come to an exhibition like this one looking for “information” about the subject, but for images that resonate on a deeper level. And while this show is consistently entertaining and will undoubtedly put a smile on your face, ultimately you’re left with a sense that artists today don’t demand much of the images they use, or indeed, of themselves. There’s too much art here that nods towards profundity, but doesn’t go much beyond fun.

Certainly the show misses what, to my mind, is Jackson’s vital role as a prophetic proto-type of the way we live now: the neurosis and the infantility, the obsession with body-transformation and gender fluidity that consume young people today were all being lived out by Jackson a good three decades ago.

Until Oct 21; 020 7306 0055; npg.org.uk