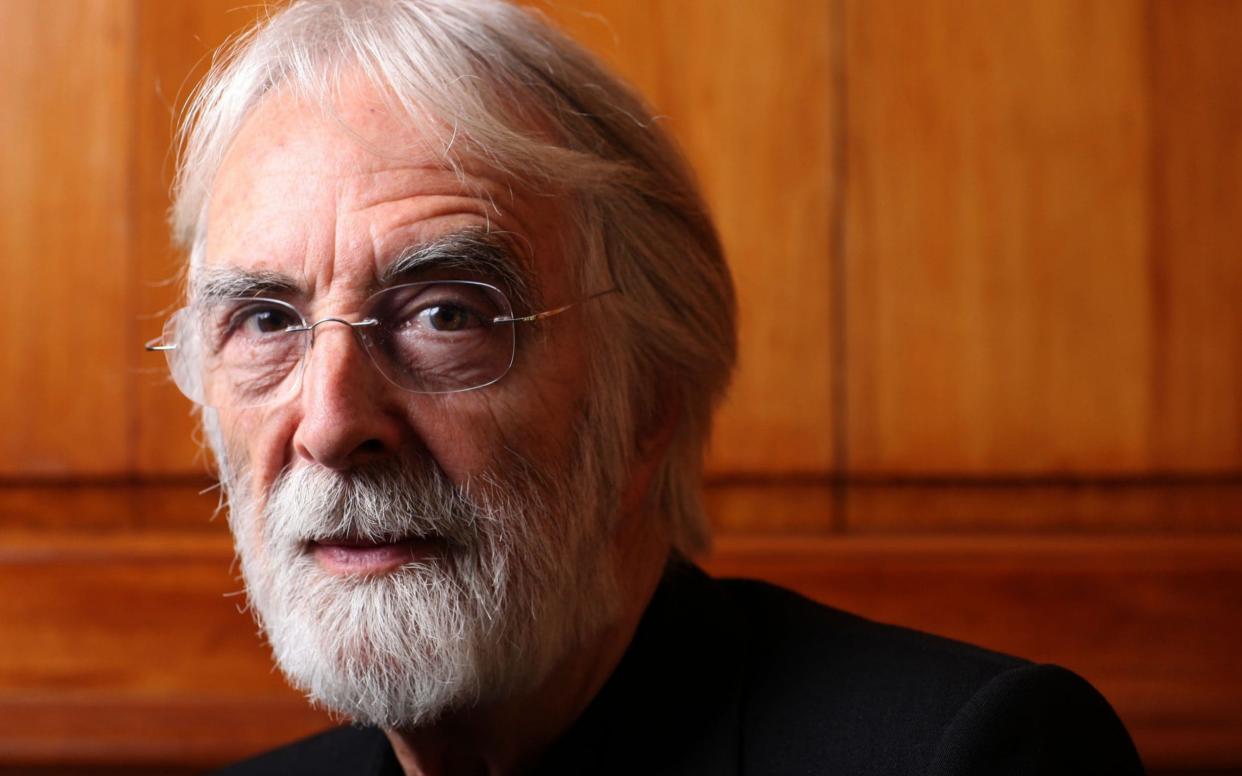

Michael Haneke interview: the master of misery cinema on selfies, Snapchat, and 'the despair that comes after the tears'

Christmas is a curious time to be releasing a Michael Haneke film, unless your idea of festive cheer is repeatedly watching a pig being slaughtered on grainy camcorder footage, or curling up for an excruciatingly tense and sexualised fracas between strangers on the Paris metro.

“Happy Haneke!”, London’s Curzon Soho is proudly and hilariously flaunting on its frontage, as they prepare for a December retrospective of the Austrian filmmaker’s work, timed to celebrate the release of his latest film, Happy End.

Now a dozen pictures into a notoriously unsettling and provocative career, Haneke has always been an easy target for satire. There was even a long-running parody Twitter account in his name, @Michael_Haneke, which gained 31,000 followers by imagining him as a cat-obsessed nincompoop, bragging about his two Palmes d’or in tween-speak and signing off all his tweets with “lol”.

The spoof worked because of everyone’s assumption that the real-life Haneke, given his films, must be dauntingly self-serious and schoolmasterish – an impression which his slightly gaunt, bearded visage at 75 does little to dispel. But those who meet him tend to be taken aback.

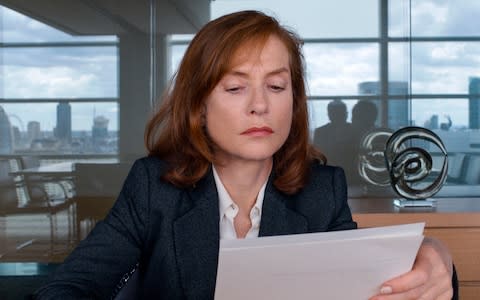

Isabelle Huppert, who has now worked with him four times, has seen the same reaction again and again. “People are very surprised when they meet him,” she tells me by phone, “because he doesn’t resemble at all the way people think he is. He’s not that serious, he can be very funny, he can be quite light. He doesn’t take himself too seriously – but he does what he does very seriously. And there’s a big difference between the two.”

It’s hard to miss a Haneke film if one is set down before you, and this is certainly the case with Happy End, a bitter black comedy about the oblivious hypocrisy of a rich family in Calais, whose concern for the refugee crisis exploding mere miles from their doorstep could hardly be less apparent.

Earlier collaborators Jean-Louis Trintignant and Huppert – playing father and daughter, as they did in Haneke’s last film, Amour – are in the hot seats, and the film begins with the typically Hanekan device of creepy smartphone footage, courtesy of a disturbed 12-year-old granddaughter (Fantine Harduin) with potentially murderous Peeping Tom tendencies.

Fold in some uncomfortable racial tensions with the Moroccan household staff, not to mention the euthanasia wish of Trintignant’s character, and the film feels like a virtual checklist of pet Haneke themes going right back to his early days: his 1989 debut The Seventh Continent, for instance, featured a seemingly unproblematic middle-class family who calmly decide to trash all their belongings and die.

Is he pessimistic? It’s beyond that. More clairvoyant, if that’s a word in English. Like a dark prophet.

Isabelle Huppert

In 2012, Amour won Haneke the second of those Palmes d’or, following The White Ribbon in 2009, and went on to remarkable success internationally, achieving a pretty astounding five Oscar nominations, even for Best Picture – not to mention Best Director for Haneke, and Best Actress for the astonishing Emmanuelle Riva.

It would be unfair to expect Happy End – far more oblique and teasing as it is – to repeat these exploits, but it came home not only awards-free from Cannes, but with far less unanimous critical support, too. A dyspeptic tableau which keeps its characters at arm’s length, the film edges into comic territory much more often than we’ve come to expect. “There are more funny moments than most,” Huppert agrees. I wonder why this particular story urged him to tackle it with such mischief.

He has a ready answer. “The hypocrisy and the lies of these characters, which we also share – that’s not something you can sell any more as a tragedy. You can only sell it as farce. Tragedy, as a form, has emigrated to the third world.”

Even though he usually understands questions perfectly well in English, Haneke prefers to answer in his native German. It gives him a means of hiding behind language, in his twinkly way, by getting the collusion of his translator in smoothing out his answers. Still, he’s quick to chuckle when he gets going, and sometimes blurts out part of an answer in English before he’s quite figured out what to say.

Huppert, for one, feels strongly that his directorial vision has remained forcefully original and largely the same, however quickly the world is changing around him.

“I don’t believe that people change,” she says. “From the very beginning he’s had a certain way of looking at the world, from Benny’s Video and so on. Is he pessimistic? It’s beyond that. More clairvoyant, if that’s a word in English. Like a dark prophet.”

Still, in a body of work so profoundly concerned with the ways we communicate and the media we consume, Haneke has had no choice but to respond to the swift impact of technological change. Benny’s Video (1992), in which a teenage boy addicted to screen violence kills someone on camera, is a tragic fable for the VHS age; by Hidden (2005), CCTV surveillance is everywhere, and now Happy End has Harduin’s phone-obsessed tween skulking around to document her own family’s dirty deeds.

“I haven’t followed those developments deliberately,” Haneke explains, “but of course I’ve heard about Snapchat, and the way in which you make a statement and then a couple of seconds later, it’s gone. I find that completely fascinating.”

How does he react to the new generation of potential Bennys, walking around with smartphones all but welded into their palms? “If they want to do it, let them do it. Obviously I find it a pain when every couple of yards on the street somebody says, ‘Can I have a selfie with you?’. It’s flattering, but it’s also pretty irritating.

“There is that old famous saying about people being famous for one second. With everybody placing their photographs online, that’s what Facebook lives off, of course. But if this is somebody’s obsession, or their perversion, that’s absolutely fine by me. It doesn’t bother me too much.”

It’s telling that Haneke misremembers Warhol’s quote about 15 minutes of fame – telling, because in the moment-to-moment churn of social media, that original prophecy now seems like a massive overestimate, and one second actually feels a lot closer to the mark. He agrees and laughs. But there are moments when the odd stern declaration does slip out, too.

“What there is undoubtedly, for young people in particular, is a certain danger of addiction.”

In 2007, Haneke was given the opportunity to remake one of his films into English for the first time. It was Funny Games, his excruciatingly tense 1997 home-invasion drama, which was expressly designed to make us question the entertainment value of watching a bourgeois family irrationally terrorised by two preppy psychopaths – one played by Benny himself, Arno Frisch.

A remake, which wound up starring Naomi Watts, Tim Roth and Michael Pitt, was the last thing anyone was expecting, but he had his reasons. “When I made the Austrian version, I was sure that it would reach the audience that it was intended for – namely consumers of video violence. But of course it didn’t, because it was spoiling their fun, in the sense that it wasn’t giving them what they wanted.

“Also, it was a German-language film, and subtitled, and therefore inevitably got a smaller audience. So when the offer was made to remake it in English, I wanted to try it out, only to discover that that didn’t work either. Because again, people felt that it was spoiling the pleasure they want to find in that kind of violent film.

“Luckily, or interestingly, now, it’s a big hit on video, and has become a cult film, and everybody seems to have seen it. But I have to ask myself, how are they watching it? Are they actually consuming it in order to get aroused, after all? It’s the question that Stanley Kubrick asked with A Clockwork Orange, because the way the film was consumed was not the way he intended it to be. And that’s definitely a problem.”

Haneke’s critics could easily seize on such pronouncements as an indication that he’s well-nigh impossible to please, and that his finger-wagging dogma has gone too far. It’s reasonable to ask whether the ideal audience he craves – first showing up en masse to submit obligingly to being told off, and then refusing all enjoyment because that’s the way he wants it – truly exists.

That said, the internal debate his films prompt, even if it’s an argument you also want to be having with their creator, never ceases to be worthwhile. Funny Games is the classic case. It’s usually thought of as Haneke’s most violent film, because of the horrendous suffering inflicted on the couple and their child. But we see almost nothing, as he is at pains to point out.

“The action itself is not shown, because the danger then for the audience is that a false identification would take place. You identify with the act of violence, too easily, in many films. Here it’s about identifying with the result of violence.”

Inevitably, this approach places the burden on Haneke’s performers to convince us implicitly of what we don’t see happening explicitly. The treatment of actors on – and indeed off – film sets is a subject about which the industry is currently steeped in self-doubt. It will be hard for many viewers to watch the rape scene in Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris ever again after hearing Maria Schneider discuss the conditions she was placed in. Meanwhile, a retrospective inquest into Lars von Trier’s cinema of cruelty can’t be far off, either. Where does Haneke draw the line in his own methodology?

“I always think about these things in advance, rather than on set, so that it doesn’t come to that point. It’s about finding the adequate and appropriate vehicle for conveying these things. Certainly, I wouldn’t never do anything in a film which the actors were not comfortable with playing. They feel protected when they’re with me.”

If there’s one person who would know what it feels like to be at the receiving end of Haneke’s most gruelling provocations, it’s Huppert, who gave a staggeringly brave performance in The Piano Teacher (2001) as a self-mutilating, sexually unhinged music professor.

“The physical scenes are the tricky part, because they have to reflect reality,” she admits. “But when he feels that he has chosen the right actor, he really lets them be completely free. He has no desire to control the actor, no preconceived ideas of what the character should be, what the actor should do on screen. That’s why I love working with him, because it feels so freeing.”

Excluding the small role Toby Jones plays in Happy End, Haneke has only once worked with English-speaking stars, on that Funny Games remake – though he says that “famous actresses, especially” are often propositioning him to collaborate. Part of the reason he hasn’t obliged could be a distinction he draws about different acting styles, which happens when I single out the fantastic performance of Susanne Lothar as the brutalised housewife, hollowed out by grief and incomprehension, in the original Funny Games.

“You can’t expect the same thing from anybody,” he says. “So Suzi Lothar loved those scenes, and got out of herself, went beyond herself. She saw it as an acting challenge. Naomi Watts, who played the part in the remake, didn’t do those scenes as well, but there were other scenes she could do better. Some people have strengths here, some have weaknesses there.

“[Naomi] thought about things very differently – and that’s a very common situation with actors in America. Because, as a result of the way they train, they don’t find it easy to tackle, or to engage with, the despair that comes after the tears.”

I’m about to ask a further question, but Haneke interrupts with a sudden switch to English, to finalise his point. Somehow hearing his words in my own language, but with his doom-laden accent, makes them sound for an instant like the least reassuring thing I’ve ever had said to me.

“If you are in a concentration camp, and your kids are killed, you have no tears, Ja?”

Ja. This is exactly why his lab-rat experiments in testing the human condition – remorselessly unsentimental, hideous in their hypothetical charge – continue to make us shudder.