Met Gala History: How the Biggest Night in Fashion Came to Be

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Marvi Lacar/Getty Images

The first Monday in May is one of fashion’s most anticipated nights: The Met Gala. From Zendaya’s light-up Cinderella gown to Blake Lively’s red carpet transformations to Billy Porter’s show-stopping glitz and glam, the Met Gala brings together our favorite celebrities, influencers, and fashion icons. This year on May 6, the exclusive list of invitees will attend the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute gala dressed to the theme of “The Garden of Time.” While you make bets on who will understand the assignment, let’s dive into the history of this annual tradition — which goes back longer than you might think.

FASHION-US-MUSEUM-EXHIBIT

Fashion for a cause

As avid followers of the Met Gala may know, the purpose of the soiree is to raise money for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. Since its inception, the Met Gala has, in essence, been a charity event. But the founders of the Met Gala did not invent this idea; since models began strutting up and down the runway in fashion shows, various organizations and individuals seized upon fashion’s ability to evoke deep emotions in order to raise money for social causes. These “fashion activists” date back to the early 20th century, and later influenced the creators of the Met Gala.

One of the first recorded events of this kind took place at New York’s Ritz-Carlton hotel in 1914. Known as the “Fashion Fete,” it was organized by the then-Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase. The city’s elite, including Alva Vanderbilt, Marion GravesStuyvesant Fish, and Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, all attended. The fashion show had two goals: first as a charity event for European families whose breadwinners were fighting in or lost to World War I, and, two, to showcase American fashion design in lieu of Parisian couture, which was unavailable due to the war. At the time, the fashion industry was an important employer for Americans in an unstable wartime market. The industry and its leaders understood that they were paramount to American economic strength and morale.

But wealthy white women were not the only ones to partake in fashion shows for a cause. The rise of the charity fashion show coincided with another important transformation of American society: the Great Migration of African Americans escaping Jim Crow’s South. The arrival of Southern rural migrants to Northern urban centers like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia massively increased the population in Black neighborhoods almost overnight. Poor, working class, and middle-class families were forced together into a relatively small geographical area. To distinguish themselves from newcomers, elite African Americans created private spaces where their class and wealth could be shown off. Their gatherings of choice? Church and charity fashion shows.

These two spaces often intersected, with the church frequently being both the venue and the cause. “Fashion parading” (as it was then known) was an opportunity to unveil new, fashionable clothes, to put money towards advancing African Americans communities, and to show newcomers how things were done in the North. Additionally, because Northern cities in the early twentieth century were still informally segregated, African Americans — even if they had money to spend — had limited access to department stores where fashionable goods were sold. Instead, they had to rely on mail-order catalogs and Black dressmakers to furnish new wardrobes. And where else to show it off if not attending, or better yet, walking in a fashion show for a good cause?

During the 1920s, the press reported on scores of such events. For example, The Pittsburgh Courier reported on an October 23, 1925 benefit fashion show at Harlem’s Manhattan Casino attended by 2,000 people. In addition to the latest fashion, the show also included a hand-painted shawl by the famed Harlem Renaissance artist Augusta Savage. In 1924, Half Century, a Black women’s magazine, discussed a Chicago benefit for the Y.W.C.A. that brought out the city’s “brilliant array of beautiful women” in the latest “hats, gowns, and furs.” The clothes, modeled by the community’s own women and men, were shown off in a display of respectability and racial pride. One of the biggest events of that decade was a benefit to erect “a child helping and recreation center for colored children” in Harlem. According to the Pittsburgh Courier, nearly 10,000 people came to Madison Square Garden to see the young, Black models in fashionable styles, elaborate hats, and luxurious furs and jewelry.

With the decade-long Great Depression following the 1929 stock market crash, benefit fashion shows’ popularity diminished, but they did not disappear. During and after World War II, these charity shows continued to be an effective tool for fundraising and for mobilizing middle-class women, who saw them as an alternative to more overtly political and social activism.

Preserving American fashion

The idea for the Met Gala first emerged after World War II. The Apple TV show, The New Look, captures (although with more than few liberties) the extent to which the war had immobilized the French fashion industry, just as it had during World War I. Back in the United States, Eleanor Lambert, a prominent fashion publicist, saw another opportunity to push American fashion to the center stage. She teamed up with Dorothy Shaver, the president of the retailer Lord & Taylor, who agreed that American fashion (in particular its industrial epicenter New York), had a once-in-a-lifetime chance to surpass French fashion. Lambert and Shaver made it their mission to advance, promote, and preserve American fashion — and the Costume Institute was the perfect place to pursue this goal.

Portrait of Eleanor Lambert

Known as the Museum of Costume Art before it merged with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1946, the Costume Institute relied almost exclusively on a volunteer force of women who felt strongly that fashion should be preserved like any other form of art. It was thanks to funding from the fashion industry that in 1959 the Costume Institute officially became a curatorial department at The Met.

For mid-century women who wanted to make a difference, fashion shows were a popular and accessible option. Middle-class women like Lambert and Shaver rarely worked outside the home, but the fashion industry, considered a “feminine sphere,” was seen as an exception. It presented women with opportunities to advance to leadership positions and influence how American dollars were invested without being labeled “unwomanly.” Eyebrows might be raised if a middle-class woman was running for office in 1942, but organizing a party? That wasn’t an issue.

In 1948, the inaugural gala was not live streamed to millions of people, nor was it extensively covered by the media. Even Vogue didn’t mention the event. The fashion industry’s trade publication — the magazine intended for those who worked in fashion — Women’s Wear Daily (WWD) was the only one to report on it. Lambert, who chaired the organizing committee, told WWD that “for a long time it has been said that the fashion industry should have one big get-together each year.” Lambert wanted it “to be one of the gayest and most beautiful parties New York has ever seen, and we hope in one evening to raise all the money necessary to maintain the facilities of the Costume Institute.” Taking place at Rockefeller’s Rainbow Room, it was a private, exclusive industry event. Quickly, the event became known simply as “The Party of the Year,” and drew the cream of society and the fashion industry.# Before Kim Kardashian created a media storm by wearing Marilyn Monroe’s historical dress on the Met red carpet, the gala nights featured a parade of industry bigwigs wearing historical garments from the museum’s collection.

The Met Gala today

So how did the Met gala leave this sphere of society events and morph into the very public celebration it is today?

Metropolitan Museum Costume Institute Ball 1978, New York

The tide started changing in 1972 with the entrance of Diana Vreeland, a groundbreaking fashion editor turned special consultant to the Costume Institute. After she revolutionized Harper’s Bazaar from 1936 to 1962 and revitalized Vogue in 1962, Vreeland turned her visionary creativity to the costume exhibitions at the Met.

Vreeland was not trained as an artist or fashion historian, but she had a talent for evocative storytelling, which previously transformed the magazines she edited into fashion-forward, youthful publications. She also had a close and extensive network of cultural influencers she harnessed to her new goal: making blockbuster fashion exhibitions that would persuade museums and their audiences to appreciate fashion like any other form of art.

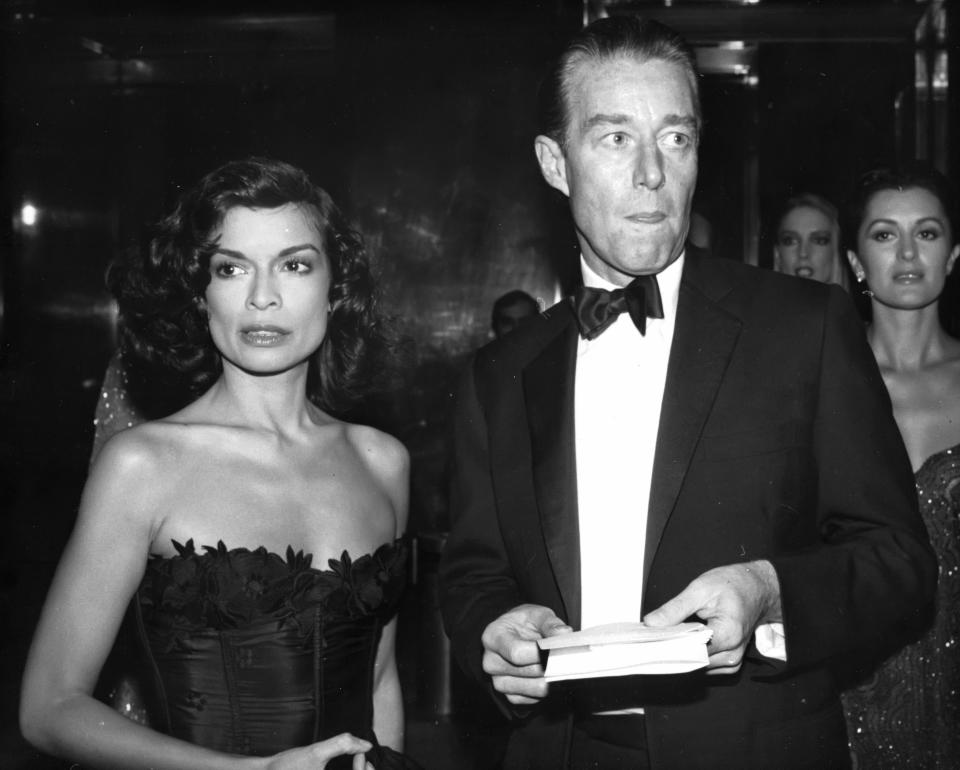

Bianca Jagger With Halston

Vreeland’s first move was to host the gala at the museum itself. Her second was to tie the annual theme to the exhibition’s topic. Vreeland leveraged the emerging 1970s celebrity culture by inviting not just society women to attend but also actors, famous designers, and models. She recruited celebrities like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who chaired the 1976 gala, with a theme tied to an exhibition on Russian costumes. Some of the 650 guests who paid $150 to attend wore ensembles from Yves Saint Laurent’s Russian collection. During her time overseeing the Met Gala, Vreeland was criticized for blatantly ignoring historical facts in favor of a provocative visual presentation and for shameless mixing art and commerce. But she was simply recognizing the fact that art has always been entangled with commerce, and fashion is no exception.

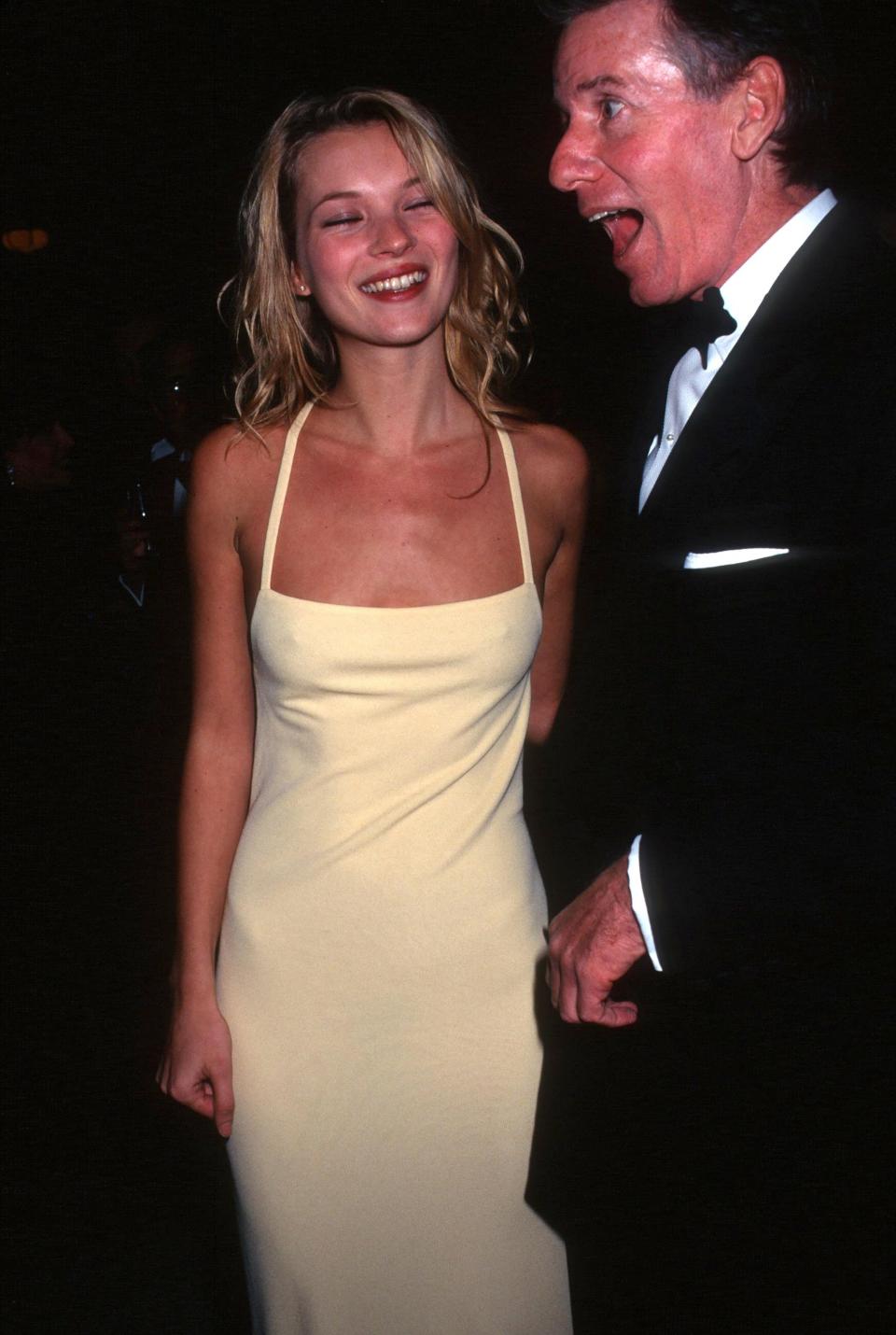

In 1995, when Anna Wintour, Vogue’s editor-at-large took over the helm of the gala, she built on Vreeland’s legacy by making the event even more celebrity-oriented. At the same time, the curators at the Costume Institute, including the now-retired Harold Koda (who worked under Vreeland) and his successor Andrew Bolton, continued to perfect Vreeland’s immersive exhibition-making. The gala reached a fever pitch with the 2016 release of the documentary film The First Monday in May that immortalized Wintour’s reign over the meticulously orchestrated event. “Since Anna Wintour has taken over the Met ball,” said the late Andre Leon Talley in the film, “it has become the Super Bowl of social fashion events.” Vreeland’s $150 admission ticket pales in contrast to the current $50,000 price tag.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Exhibition

1995 Costume Institute Gala at the Met

True to the gala’s legacy of “fashion activism,” attendees sometimes use the red carpet to raise awareness of current events. In 2021, New York Representative Carolyn Maloney, an advocate for the Equal Rights Amendment, wore a dress in tribute to women’s suffrage activists. Maloney donated her dress to the New York Historical Society, where this piece of fashion activism history will be preserved for generations to come.

The 2021 Met Gala Celebrating In America: A Lexicon Of Fashion - Arrivals

Museums all over the world now collect, preserve, and display fashion exhibitions regularly. In 2023 alone, in addition to the Met’s tribute to Karl Lagerfeld, the Brooklyn Museum paid homage to the late designer Thierry Mugler, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London staged the show Africa Fashion, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo hosted the show Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams. And with a record 53 million viewers of Vogue’s 2023 Met Gala stream, it’s clear that fashion and its history holds a special place in our culture.

This article was produced with Made By Us, a coalition of more than 200 history museums working to connect with today's youth. It was edited by Cameron Katz.

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue

Want to read more Teen Vogue history coverage?