Should We Be Running Background Checks on Our Tinder Dates?

Dana Rozier matched with a guy on Hinge and went out with him the same day at a bar in her neighborhood in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. Hanging out at her apartment afterward, where she invited him inside to eat tacos, she told him that she liked his sweatshirt, which said “We’re not really strangers.” He told her that he had made it himself, although she knew it was actually the name of a popular card game that sells clothing merch. Before he left, he gave Rozier the sweatshirt. The inner tag was cut out.

Later that night, Rozier, 29, called him through Hinge to let him down gently. He seemed to understand. But two days later, a flower delivery arrived at Rozier’s apartment. “So then I see that this guy that I had just met two days prior that I only went out with once sends me a beautiful bouquet of flowers,” Rozier says. “And the card said, ‘We’re not really strangers.’ And, like, does he know how creepy that is?”

Rozier’s friends were concerned. One of them posted in a private Facebook group with 142,000 members who sleuth online to find long-lost relatives or run background checks on possibly shady figures, using one of the many sites that aggregate a hodgepodge of public records for a fee.

“So my friend is dating this new guy and I just want to make sure he doesn’t have a criminal background,” Rozier’s friend posted, along with her date’s full name, age, and location. Soon, two people reported back: According to the background check websites they used, he had two traffic violations but no criminal record.

Rozier was only “20 percent scared,” she says, but “you’re always afraid of the unknown because you never know what people are capable of.” She’s describing a familiar, vaguely disconcerting vibe many women dance around on dates: Is he normal...or weird? And is he weird in the fun way or the scary way where he just might unalive me later?

CSI: First Date

Today, it’s a fact of modern life that if you want to meet someone, you’re likely going to have to go through a dating app. Tinder, founded in 2012, is still the most-downloaded dating app in the U.S. with nearly 1 million monthly downloads. Bumble and Hinge trail closely behind.

But people, especially women, have had notoriously bad experiences on the apps. More than half of women under 50 who have used a dating app say they’ve been sent a sexually explicit message or image they did not ask for, and 1 in 10 have received threats of harm. In a particularly terrifying example of the dangers of online dating, a man in Texas was recently charged with aggravated kidnapping for allegedly assaulting a woman he had met through Bumble and holding her captive for five days.

Dating apps are well aware of these dangers and have introduced some features—like the ability to block profiles and phone numbers—to help protect their users. Some safety measures have been baked into the apps since the dawn of swiping. Tinder, for example, has never allowed users to send each other images within the app so, no, you’ve never actually received an unsolicited dick pic there. The app now also offers in-app photo verification to curtail catfishing, but they still haven’t managed to implement ID verification, a feature they announced was in the works all the way back in August 2021.

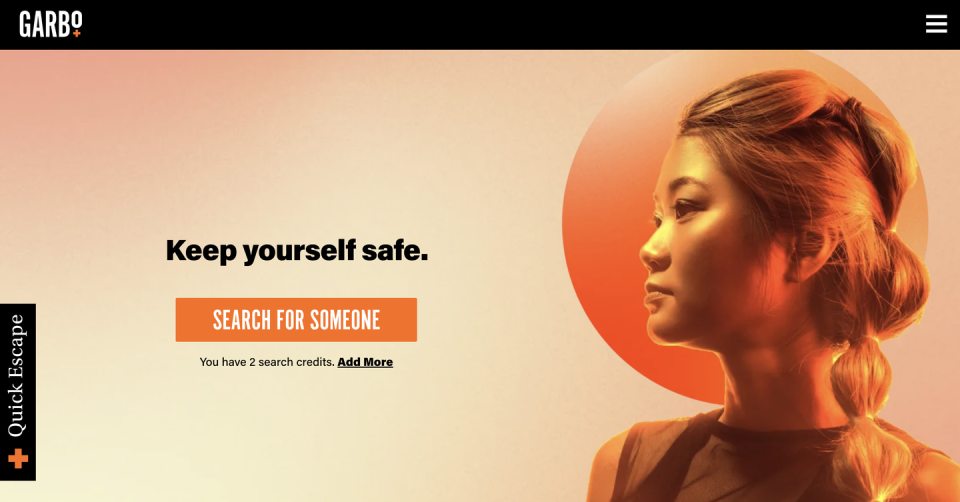

Last year, to great fanfare, Tinder—as well as dating apps Stir, Match, and Plenty of Fish, also owned by the Match Group—introduced the ability to easily background check potential dates with a service called Garbo. With just someone’s first name and phone number, Garbo users can perform quick background checks and find “reports of violent and harmful behavior” that focus on “arrests, convictions, and sex offender registry records.”

Each search costs $2.50, and it’s a smoother experience than going through any of the clunky online background check sites, which range in cost from $20 per month for all-you-can-search access to $90 a pop. Some of these sites even use scare tactics (“What you find in [Name]’s report may shock you”) to finagle people into paying. Some of Match Group’s apps allow users to click through to Garbo directly to gain access to two free search credits, but iPhone users on Tinder have to navigate to the Garbo website separately and claim their free credits by inputting “Tinder” into the “How did you hear about us?” box.

A year after its launch, Tinder and Garbo declined to share user numbers with me, so it’s hard to know if more women are background checking their dates through the dating app or if they’re altering their dating choices based on what the service uncovers.

“Tinder invests in product innovation and provides proactive member education and intervention to help keep members safe. This two-pronged approach ensures members have control over their Tinder journey, enabling them to make choices based on their individual comfort level,” a spokesperson for the company said in a statement. “While Tinder can’t solve for every possible outcome, we can make sure we’re giving members the tools and resources they need to have the best dating experience possible.”

Translation: The onus of vetting dates still rests almost entirely on the user, with Tinder—and many other apps—sidestepping their own responsibilities. Now, more than ever, daters are left to sort through the avalanche of information on their own about the stranger on the internet that they might meet for a glass of wine.

All these tactics raise thorny new questions: How much should you dig into the past of the person behind the profile? Do we need to approach a first date with the rigor of a criminal investigation? Where do we draw the line between protecting ourselves and knowing way too much way too soon and possibly infringing on someone’s privacy?

“Maybe one less bad thing”

Garbo’s founder, Kathryn Kosmides, began the company after her own hellish journey escaping an abusive relationship with someone she met on Tinder. Their relationship began with “love bombing,” Kosmides says, and quickly turned abusive. He watched her every move and wanted access to all of her text messages and even her calendar. After his behavior escalated to physical violence, she began calling abuse hotlines to plan her escape. But even after she left him, the stalking and online harassment continued. Kosmides sought an order of protection and quickly found herself bewildered by the complicated justice system.

“The police would say things like ‘We’re too busy dealing with murderers to deal with this,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, maybe you want to prevent one,’” she said.

As Kosmides’s case against her ex went through the criminal and family court systems in New York, she was frustrated that his charges related to stalking and harassment were downgraded to minor violations and that criminal histories often didn’t transfer between states.

“I was like, ‘Wait, the states don’t even talk to each other?’” Kosmides says. “And that’s really what started it. So many survivors say the same thing: You report for yourself, but you keep going to protect the next person. I just wanted this person not to be able to hurt me or anyone else again and have a record that people could easily find.”

Women who have used Garbo in the last year say they are finding the background check both a reassuring tool in their safety arsenal and a confusing ethical quandary. Christina Marie, 32, from Los Angeles, found Garbo through TikTok, where it has more than 40,000 followers, and went down the rabbit hole of watching their videos, which encourage women to look up their dates and educate followers about dating red flags, such as controlling behavior. (Some women leave comments like, “Wish they had this 7 years ago so I could have avoided having my life destroyed over and over ever since I met my ex.”)

“I was like, ‘This is so accessible, so easy, so affordable, and it works,’” Marie says. She hasn’t found anything alarming pop up after background checking her potential dates, but it still makes her feel a bit more secure before meeting up with strangers.

“Online dating is very scary,” Marie says. “It’s more for peace of mind and hoping you don’t find something. It was like a more peaceful process than just going blindly and just hoping that nothing happens.”

Marie encourages all of her single friends to use Garbo. “Bad things are bound to happen and if women knew about this service, maybe one less bad thing could happen to a woman.”

Puzzling through an imperfect picture

But relying on public records to vet potential dates poses a whole new set of complicated considerations: The criminal justice system from which they are sourced is deeply racist. Black and brown men are disproportionately more likely to be arrested, convicted (sometimes wrongfully so), and incarcerated than white men, which means that they’re also more likely to be flagged on a background check.

Kosmides acknowledges this. “Public records fucking suck in terms of a data source,” she says, adding that Garbo’s reports exclude things like loitering and marijuana arrests. “They’re very dirty data. There is no perfect solution,” Kosmides says. “But overall, we’ve had a really positive response that we can rethink background checks and we balance privacy and protection and have these hard conversations.”

Background checks also don’t paint the whole picture of harmful offenders—not even close. Less than one-third of rapes are even reported to the police. Of these, about 6 percent resulted in arrests, and less than 1 percent resulted in incarceration. That means the vast majority of violent men will never cross paths with the criminal justice system. And some of those men are certainly online dating.

Forensic nurse Julie Valentine has listened to thousands of survivor testimonies as she collected rape kits—science-based evidence of sexual assaults—throughout her career. She was also one of the leading researchers on a study of “dating-app-facilitated sexual assault,” a topic that has rarely been studied more than a decade after dating apps hit the mainstream. The study found that assaults that occurred on a first date from an online dating app were more violent than non-app based ones and almost a full 60 percent of these victims self-reported having a mental illness.

“A lot of perpetrators are pretty good at figuring out who’s more vulnerable and also who’s less likely to be believed,” Valentine says. “There are a lot of hidden rapists and abusers in our society because so many victims don't report.”

Because of society’s failure to keep us safe, women have come up with ingenious (and sometimes controversial) methods to warn each other about scary men, including some highly organized whisper networks. There are well-meaning strangers online who will background check your date for free, and localized Facebook groups in most cities with names like Don’t Date Him 🚩, where people post screenshots of dates’ profiles with details of their bad experiences.

Alex Espinosa, 32, from Savannah, Georgia, started online dating after leaving a long-term relationship and soon had some unsettling experiences. She went out with one man she later found out was married. After another first date, a woman sent her a message to let her know that her date had a violent history—she had found Espinosa through a “Are We Dating the Same Guy?” Facebook group.

“It was pretty disconcerting because I felt that I was a pretty good judge of character,” Espinosa says. “This guy seemed totally normal.”

Espinosa also found Garbo through a TikTok ad. She ran her date’s common first name and phone number, and Garbo returned results from several people with criminal records that may or may not have been him. But she decided to trust her gut and not see him again. Now, she uses Garbo to background check every first date, and she’s found criminal records and misdemeanors like DUIs come up on potential dates, leaving her to sift through the information and then figure out what to do with it.

“Things like shoplifting wouldn’t be that big of a deal. That’s just me personally, especially if it’s an older charge,” she says. “But violent charges, like domestic violence, I definitely would not go on the date.”

Becky Corbin, 27, from Tulsa, Oklahoma, had a similar experience of agreeing to meet up with a guy from Hinge who seemed “really normal.” But after he canceled their first date at the last minute and Corbin told him she no longer wanted to meet, he sent her aggressive, angry messages.

“It just clicked in my brain, oh yeah, I work for a national bail fund and definitely know how to access all local court records,” Corbin says. When she looked him up on the Oklahoma State Court Network, where anyone can search public records for free, she found three protective orders from three different women.

Because of her work in criminal justice reform, Corbin does not believe in writing someone off forever for the worst things they’ve done. So she wrestles with weighing the benefits of background checking her dates versus the nebulous informational overload they can provide (does she really want to know if someone’s been divorced?) as well as whether or not to inform them that she is doing so.

“It’s tricky,” she says. “It feels distrusting to search someone’s background like this, but also it makes me feel a little more safe and a little more secure of like, well, at least I did my due diligence of the least I could do to keep myself safe. It’s tragic that that’s a consideration we have.”

Somewhere between vigilance and paranoia

I’ve been online dating, on and off, for a decade. Not only have I never background checked a date, I have a policy of not looking up a single thing about them before I meet them. I try to judge people based on their profile and our brief conversation and hope for the best. To be a woman is to know in your bones that there’s the possibility of violence wherever you are—whether behind a phone screen, on a jog, or in a relationship (especially if it’s a heterosexual one). But it’s exhausting to walk through the world with that kind of vigilance before it turns into paranoia. Dating is supposed to be fun, right?

There are also more existential questions of how one should ethically and intellectually use the information that might be unearthed by a background check. Should it matter that a potential date was arrested for shoplifting when they were financially desperate in another stage of their life? Does a DUI charge make someone an undesirable partner? What if that was a catalyst for positive change, as huge missteps often are? Should we forever socially punish those who served their time and are now trying to move forward? The information background checks yield provide little nuance for life’s many mistakes and bad choices, from which none of us are immune. I’d definitely feel violated if I found out strangers were posting my name, photo, and phone number on a Facebook group to find out everything they could about me—but then again, I don’t think I have much to hide.

But for many of the women who use Garbo and other services like it, it comes down to doing whatever they can to protect themselves in a world that has never made their safety a priority.

“If something happens and you knew this was an option and you didn’t take it and you didn’t see something that would have changed your mind about your own safety in this situation, what would you say to yourself?” Corbin says. That’s the haunting—and deeply unfair—question that will stay on my mind the next time I swipe.

You Might Also Like