The Mega Rich Are No Strangers to Extreme Tourism Disasters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

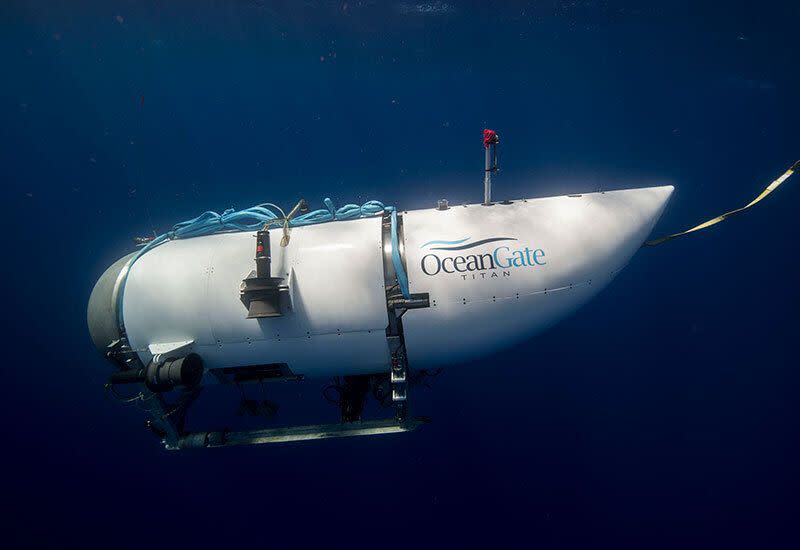

History is full of ill-fated expeditions and earlier this week the world learned that another one had come to a terrible end. In a statement released Thursday afternoon, OceanGate, the company behind the Titan submersible, announced, “we now believe that our CEO Stockton Rush, Shahzada Dawood and his son Suleman Dawood, Hamish Harding, and Paul-Henri Nargeolet, have sadly been lost.” International rescue teams had been searching for the vessel for the better part of the week and debris discovered on the ocean floor near the Titanic shipwreck had led experts to believe the submersible had imploded during its descent.

Questions about the expedition were raised almost immediately after the submersible lost contact with its surface vessel on Sunday, June 18th. The public wanted to know: who was on it? Was it safe? Who regulates these types of trips, and who is paying for these rescue efforts? Experts asked about safety protocols and possible design flaws. Pretty much everyone wanted to know why five men, four of whom reportedly paid $250,000 for the privilege, crammed themselves into an experimental minivan-sized vessel for a two-hour trip to the bottom of the ocean.

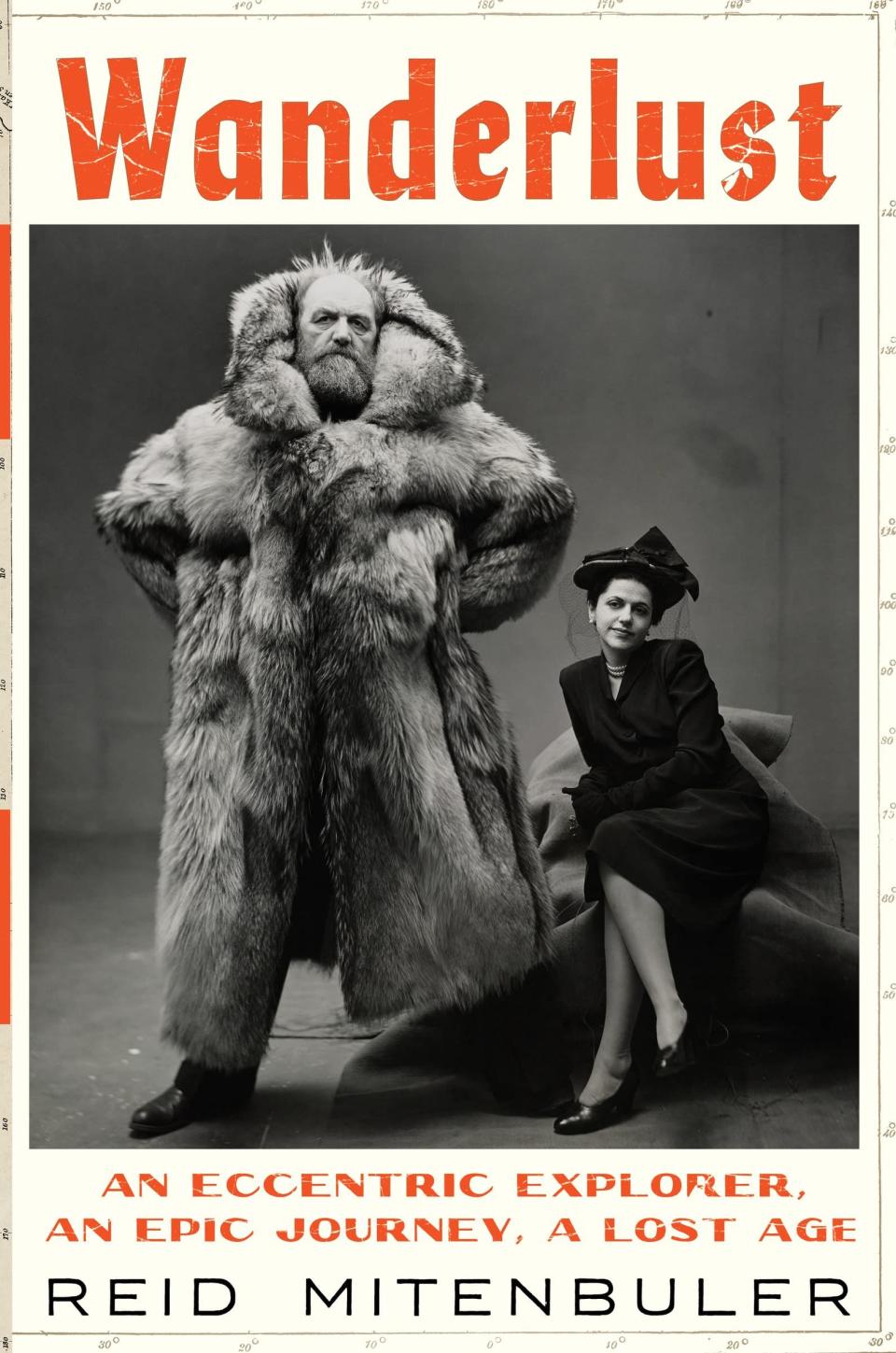

To answer the last question it may help to look to the past. Reid Mitenbuler, whose biography of arctic explorer Peter Freunken, Wanderlust, was published in February, has read thousands of letters and diary entries written by some of the world’s most intrepid expedition leaders. In a phone call this week from his home in Los Angeles, Mitenbuler said he isn’t surprised when individuals seek out dangerous trips. “Even though the golden age of exploration came to an end nearly a century ago, people still want to see things with their own eyes and in the process test themselves,” he told Town & Country. “There is, as [polar explorer] Robert Peary described it, an animal urge in some to just get out there.”

Wanderlust: An Eccentric Explorer, an Epic Journey, a Lost Age

amazon.com

But nature doesn’t care about man’s impulse to see the unseen, or his hubris to take on the elements. Here, a look back at when extreme tourism went wrong.

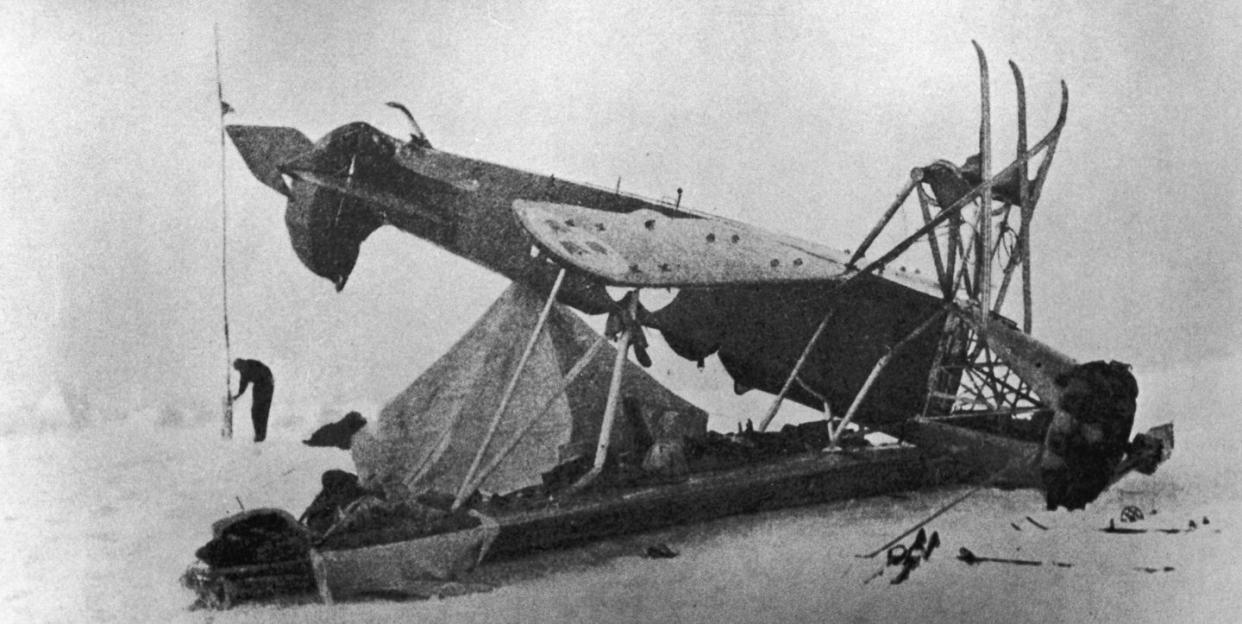

Arctic Disaster

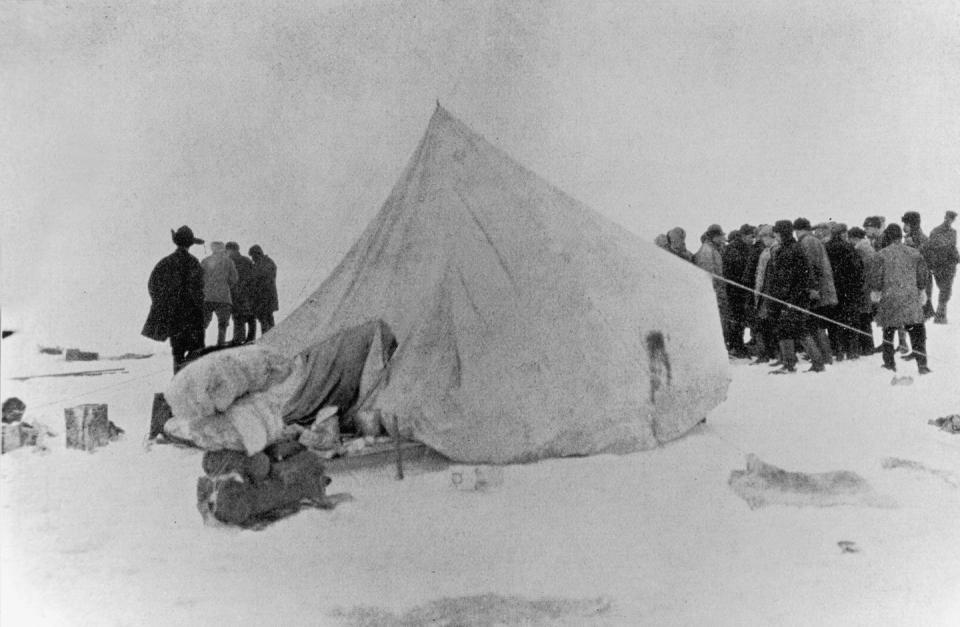

Umberto Nobile’s voyage to the North Pole in 1928 in the dirigible Italia went well at first. The Italian aeronautical expert had already successfully flown to the North Pole once in 1926, accompanied by the noted arctic explorer Roald Amundsen. Nobile traveled without Amundsen on his second trip (the two had quarreled after Amundsen accused Nobile of taking too much credit for their expedition). Nobile and his crew of Italian scientists reached the pole but could not land because of high winds. They were able to drop an Italian flag and cross that had been blessed by Pope Pius XI on the spot. On the way back, however, the dirigible had a mechanical problems and crashed onto the sea ice. Several men were killed immediately and Nobile, who was badly injured, was stranded along with the rest of the crew.

A massive international search was launched during which several rescuers died. Amundsen joined the rescue efforts, but he disappeared and was presumed to have been killed in a plane crash. After seven weeks, a float plane reached the survivors but was only able to transport one person. When Nobile took the spot while his crew remained stranded until a Soviet icebreaker made its way to their camp, the public turned on him. Why had he allowed himself to be evacuated first? Was a second trip to the North Pole really necessary? Why had he put so many people at risk? Nobile argued that he had acted correctly and that the trip had scientific merit, but he returned to Italy in disgrace.

Deaths on Everest

Sandy Hill (formerly Sandy Hill Pitman) had already attempted to summit Mount Everest twice when she finally made it to the top in 1996. An enthusiastic climber and wealthy member of New York society (she was married at the time to MTV CEO Bob Pittman), Hill had paid $65,000 to participate in the trip, which run by a company called Mountain Madness. The ascent went well but weather conditions deteriorated rapidly on the way down. Hill and several other climbers in her party became exhausted and had to be carried and dragged to one of the base camps. The leader of her trip, as well as seven climbers from other expeditions, died on the mountain that night.

Hill, who had been writing a daily web journal for NBC, became a lightning rod during the public outcry about the disaster. Was she a qualified mountaineer or rich dilettante who put others at risk? Was Everest overly commercialized? Had she, like Umberto Nobile, been in it for the attention? (Hill later pointed out in interviews and in an article she wrote for Vogue that she was an experienced mountaineer and had already made it to the top of six of the famed Seven Summits when she joined the Everest expedition.)

Today, the commercial climbing business on Everest is busier than ever. Billionaires jockey in long lines to get to the top.

Wealthy Benefactors

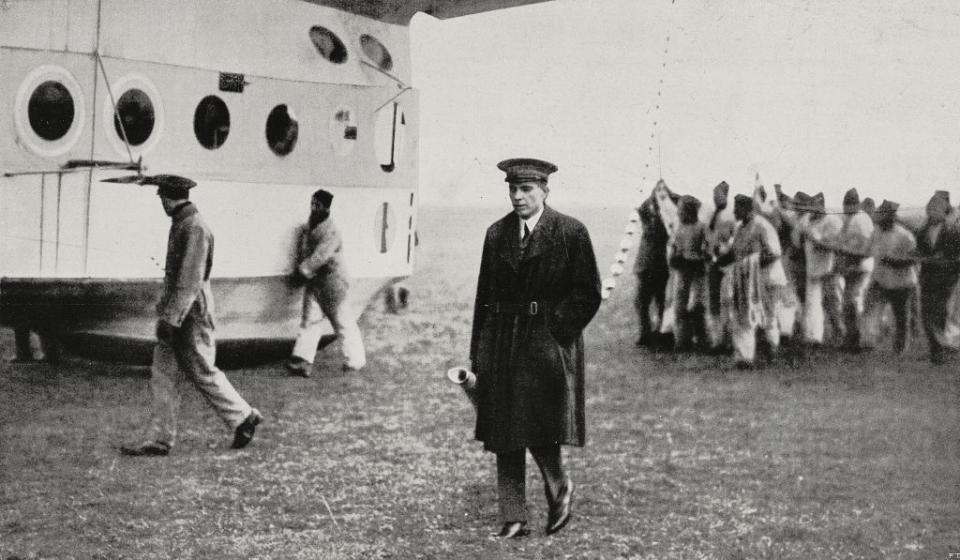

They also travel to space (some, like Jeff Bezos, aboard their own spaceships), accompany scientists on research trips to the Antarctic, and trundle into the mouths of volcanoes. Mitenbuler pointed out that there has always been a connection—often uneasy—between explorers and wealthy enthusiasts. At the turn of the last century “the public speaking circuit was very lucrative and explorers would give talks to fund their next adventures,” he said. “Along the way, they’d meet wealthy benefactors—some of whom wanted to come along on the trips.”

One example is Lincoln Ellsworth, who was the son of a wealthy Chicago businessman who paid for (and joined) many of Roald Amundsen’s arctic adventures. Louise Arner Boyd, a gold mining heiress from San Francisco, funded and made numerous scientific research trips to the arctic. When Amundsen went missing trying to find Umberto Nobile in 1926, she financed some of the rescue efforts and went along to help. “These people made significant contributions of their own,” said Mitenbuler. “And people like Freunken and Peary needed them.”

Disasters and the media

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, arctic exploration stories were so popular that newspapers sponsored trips so they could have an exclusive on the story. Accidents and rescues made compelling copy and experts and armchair strategists were enlisted to pick apart every development. Almost one hundred years later, the storm that killed Sandy Hill’s guide and seven other people on Everest spawned hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles, several books (including Jon Krackauer’s Into Thin Air, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize) and movies. This week, the Titan submersible received almost constant news coverage as well as a surprisingly vitriolic commentary on social media.

Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster

amazon.com

What would Peter Freunken, who spent years risking his life on various adventures and in attempts to rescue others, have made of the Titan trip? “Freunken was critical of expeditions he thought were dangerous or unnecessary,” Mitenbuler said, “But I think he would see a parallel and would recognize the motivation of the people in the submersible. They were curious. You can disagree about a lot things [about the wisdom and merit of the expedition], but there's still humanity here that is very much front and center.”

You Might Also Like