Meet the Top Graduates of RISD’s Class of 2021

The common denominators of RISD’s Class of 2021? I would have to say it’s their connections to nature and fantasy. Otherworldly creatures appear in the collections of Kylin Conant and Arvi Sulovari, and both are headed to the club to party. When designing Spectator Sport, Lilly Durbin had another sort of public gathering space in mind: the gym. She describes her collection as a “direct combination of the Elizabethan era and athleisure as simultaneous forms of ‘performance wear.’ It’s absurd,” she said, “but so is our current fitness movement.”

As a respite from reality, Mina Şerbetçioğlu, created an imaginary world of peopled dressed in looks with a fairy-tale quality. Anna Armstrong was seeking a different kind of escapism with her Wanderslut collection, which reclaims body-conscious dressing from the male gaze.

See these thesis projects, and more, below.

Anna Armstrong, 22, from Lexingron, Massachusetts; @wanderlust_anna

Tell us about your collection. The yellow and brown tights dresses are made of [hand-dyed] manipulated nylon stockings draped, collaged, layered, and sewn to a power mesh bodysuit base. The tights suits consist of two pairs of nylon stockings joined at the waist bands and cut so they can be put on and taken off. There was zero waste in making these pieces. [The] reupholstered resin flower bra is a pair of tights dyed blue then cut up and hand sewn to a pre-existing underwire; resin [was] poured over flowers to make resin flower bits.

[For the] cable sweater vest and sheep top: pieces were programmed and knit using the Stoll machine. I was interested in manipulating traditional Aran knitting techniques. I played with distressing the knits more with decolorant and dye and felting for the top], then I draped and hand sewed the fabric into its final form. There was zero waste in making these pieces. [The vest is paired with handwoven wire fuzz pants [made of] fabric handwoven by my dear friend, and textile artist, Benjamin Doctor. Without any cutting, I draped the pants and hand sewed everything, attaching a waistband scrap from a pair of tights. There was zero waste in making this piece.

[There are two silk taffeta pieces: The Swanhead and the Princess Dream dresses]. The first was built on the dress form by draping some individual pieces of silk taffeta and some sewn together strips and different shapes of silk taffeta. I made channels to thread wire through in order to support the swan head forms at the neckline. The drape on the second is entirely hand sewn.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

All that could disperse in the wind brought into the real on the body. To create sensations and desire driven by materiality and touching.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

The main challenges I faced stemmed from having to find other ways to work with my peers. Everything in apparel design is in proximity to the body and everything I do is incredibly collaborative. The time I was able to spend talking, experimenting, working, growing, and laughing with my peers at RISD over the past few years means the world to me. With the challenges brought on in order to protect each other through the pandemic I have realized that the will to communicate with the people that inspire me is powerful and as long as we do the work to communicate, physical proximity is not the key to collaboration.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I would spend my life making garments for people to create living poetry rather than design for mass production. I wish wearable pieces could be engaged with as art objects made to make real life more beautiful. Everything in my collection is 1 of 1. I wish fashion wasn’t so focused on commercial production and marketable desirability and more focused on making life beautiful. The beauty that you embody, the moments that you bring life into, and all of the textiles that become a part of you, do not have to be reproduced.

Kylin Conant, 23, from Mililani, Hawaii; @wildfripnips

Tell us about your collection.

This is a story of a grotesque monster desperate to find love. Through her journey of never acquiring it, she developed a definition of beauty and sexuality on her own terms. These garments are a byproduct of love, kindness, and trust within oneself. It turns out she never needed anyone to tell her what she was capable of; She just needed to tell herself.

The material choices are ones that reflect and absorb light in ways that mimic the visual natures of the ocean deep. I was fortunate to have a sponsorship from Swarovski which provided a bioluminescence to the garments.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

Pop-star, fashion culture of the ocean deep.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

The most challenging aspect was realizing the importance of caring for oneself more than one’s work. It is something I am making progress in but still trying to find a balance between. Eating, sleeping, and having fun are aspects of life that are absolutely crucial to make good work. At the end of the day I have to understand that it is okay to not be a machine.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I wish it was a kinder industry. There is a pressure to be a cut-throat, insensitive person, but even the people in power have moments of weakness and defeat. However, it is what they are able to do with that and how they use their weaknesses to become the strong people they are.

Lily Durbin, 22, from Newton, Massachusetts; @lily.durbin

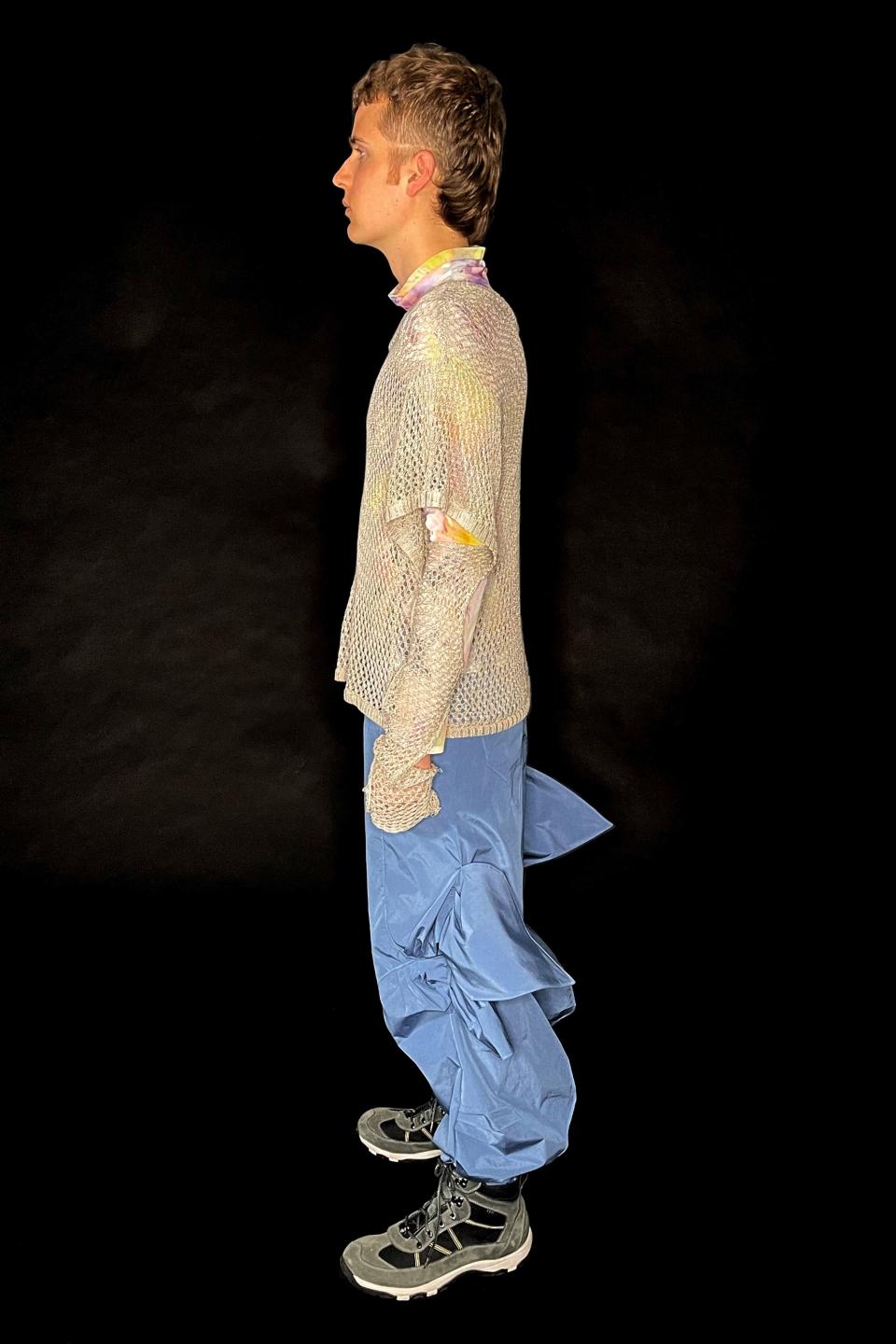

Tell us about your collection.

Spectator Sport is a direct combination of the Elizabethan era and athleisure as simultaneous forms of “performance wear.” It’s absurd, but so is our current fitness movement, especially the way we have rationalized our behavior to the point of numbness. Of course I’d get a better workout with mascara on, why not? Of course I’d avoid doing squats in public, that would just be asking for stares. Questioning why I curated my appearance and demeanor while I exercised, I was reminded of the stiff posturing of Elizabethan portraits, spectacular protective propaganda.

[The collection] blurs the line between past and present through material contradictions, utilizing lifeless stretch materials laboriously smocked by hand, silhouettes of myself working out repeated and abstracted into sweat-stained blackwork, beads of sweat embellished as sparkling Swarovski crystals, and durable ripstop transformed into a weightlessly voluminous gown and delicate hooded ruff. Outside of support from Swarovski and Spoonflower, the majority of my materials are locally reclaimed deadstock and recycled fibers to reduce the use of new plastic-based fabrics and trims. Much of the collection includes layers of material, covering the body with high necks, elongated sleeves with thumb-holes, and tightly gathered yards of fabric. These elements take up physical space and cover the body, allowing for an experience of power through protection. But much of the collection also includes moments of exposure, glimpsing an exposed hip bone, the negative space of a racerback top, a transparent coat. These elements give in to our need for validation and attention, but also allow the wearer agency to choose which body parts to display and when. Spectator Sport is a give and take, purity with hints of reality.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

A constant contradiction: Beauty living alongside discomfort and critique, a quiet unspoken rebellion.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

The most immediate challenge in making my collection was sourcing material. Like so many designers, seeing and feeling the way a material behaves is an integral part of my process. But with shopping and travel risks, I shifted my focus to making what I had into something I wanted. While I never would have bought electric blue ripstop, getting a deadstock bolt from a local business challenged me to experiment with over dyeing the fabric. Out of necessity, my process has become about fluidity, allowing for sustainable efforts through sheer resourcefulness. I’ve had to shift my mindset to one that lets each challenge and solution shape a garment’s outcome instead of holding onto its first sketch.

But I think the most difficult challenge was reminding myself that what I was doing had value. Seeing the incredible efforts of essential workers and the pain of so many families in the pandemic, I found myself questioning how I justified spending my time making clothes. But I knew I couldn’t be the only person who would go on Vogue Runway at night, who was filling their spare time creating in a moment of destruction. As I’ve increasingly shared my process online, I’ve seen how much excitement my work brings family, friends, and strangers. After this year, I think I’m finally coming to an understanding that creativity is medicinal and absolutely vital.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I could see myself going down so many different avenues because of how many opportunities the fashion industry has for change. But I think what I most naturally gravitate towards is just making clothes that are deeply considered. My fine arts background at RISD has solidified a belief that everything I do can and should be conceptually driven, and I love getting completely obsessed with a process. Fashion students spend incredible amounts of time on singular garments, from research to patterning and hand sewing, and I just can’t see myself working in any other way in the future. I believe that slow fashion will not only create the sustainable future we desperately need, but it will also emphasize the social and emotional value of what we choose to wear.

Emily Violet Frisch, 25, from Queens, New York; @emetvarda

Tell us about your collection.

Every piece is colored using natural plant dyes like goldenrod, lichen, and indigo that I’ve either foraged in the northeast US or ethically sourced with the aim of deriving light-fast colors in a complex range of shades. The process of picking, brewing, fermenting, dyeing… overdyeing and printing with these plants on silk supports the telling of my story because this exciting process, like the designs themselves, explores the way we alchemize our sense of self, through generations into who we become. Rags and Feathers is a personal mythology describing the different archetypes and influences that surround, support, and are embodied in a woman’s life.

An example of this metaphor is the 12th House Dress, piece-dyed in striations of madder, indigo, logwood, and marigolds and created in collaboration with Swarovski. This dress contains over 2,000 beads suspended in hand sewn [laddered] seams and delves into the subconscious, emotional boundaries (or lack thereof) as it descends into inner worlds. The making of this dress actually felt like the externalizing of emotions through long periods of rhythmic hand work.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

My aesthetic is expressive re-membering, reverence for the sacred, open eye inhaling, and whole hearted protection for our living planet.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

A large challenge came from the mental stress of watching COVID-19’s devastating impact on individuals and communities while experiencing the anxieties that have risen. The prevalence of racism has also been a clear signal that in all fields and especially those that are creative, compassionate conversations and respectful listening around diversity are paramount. I have questioned the point of becoming a fashion designer before, but this year I’ve ultimately renewed my voice because I am here as a daughter of an immigrant mother and intend to go great distances in work that creates empathy among divisions and fiercely defends the planet.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

By jumping into possibilities for helping rekindle mind-body connections in people, and their connections with nature, through the simple act of clothes making, mending, or wearing using sustainable techniques. I’m drawn to the way that sewing, dyeing, and handwork can be where art meets fashion. How the act of wearing a garment made with enthusiasm and love can be a transportive and life affirming experience. When I hear stories of how my grandmother and great grandmother were skilled seamstresses in China making all the clothes for my family, I realize that I am empowered by the same skills they had but with a greater freedom to express the metaphors that I feel. This expansion is not to be taken lightly for it’s an enormous privilege and voice that I wish to share. So I am inspired deeply by the learning that comes through the many steps and layers of the clothes making process and feel that sharing this space can be valuable to people’s creativity, belief in themselves and connection with each other and nature.

Joslynne Houlder, 22, from Vernon, Connecticut; @pample.mousse

Tell us about your collection.

I constructed four designs for my thesis collection, Orchard. The first garment I call Bed dress, [and] I chose this name because I had been draping it with bed sheets and I ended up using the edges or trims in the final design. I used mint-green polyester satin for the dress and silk organza that was overdyed for the T-shirt underneath. The edges of the shirt are frayed. The Root dress [is so called]... because the ropes used as cording reminded me of roots from a tree. I wanted the cords to evoke a sense of tangledness, [which is] why I knotted the exposed parts of the cords. I used a silk and linen scrim that I later acid dyed blue. The cording is cotton braided rope that was also dyed.

Flutter, or Untitled, as I am not sure of the name yet, took the longest amount of time as I had to problem solve many parts of the construction. Yellow silk taffeta, silk organza, and a silk blend stretch organza were used to create this look. I acid-dyed the stretch organza to match the model’s complexion in order to create the illusion of skin.The top that wraps around the shoulders and chest is structured with non-fusible interfacing.

“Bloom” is made using cotton siri and non-fusible interfacing. I attempted to construct this look last with satin faced silk organza that I acid dyed a peach color with the addition of non-fusible interfacing to uphold the structured “wings” or “petals.”

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

The best way I would describe my aesthetic right now is a dreamy, ethereal, fairy-esque fantasy with remnants of suburban nostalgia.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

The biggest obstacle the pandemic gave me was the inability to escape— which can go both ways in its affect to focus and imagination. I had to sit with more thoughts and feelings and put safety at the forefront, which was helpful in assessing my life outside of being a student, [which] can be hard when you are going through a rigorous course schedule. The part that was the hardest was finding ways to refresh when I felt like there were only so many things I could do. I did not lack routine for the first time in my life but the opposite, spontaneity. I missed stumbling across things…. The way I combatted this was trying to build my internal world and gathering concepts and ideas in several different notebooks that I could forget about, rebuild, and rediscover consistently. In the end, I feel the pandemic allowed me to feel more urgency to be more introspective in my practices.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

My design motives definitely stem from things that I found fascinating in my childhood. One thing I cannot deny is my love of flowers and their subconscious influence on the way I imagine and design clothing. [That the name of ] my collection, Orchard, comes from the street I grew up on, is a realization and acknowledgement of this. I’ve always seen flowers as aspirational and otherworldly in their beauty. I see my clothes as an attempt to bring my idea of the fantastical into reality through clothes I would want to wear in my own world.

If I could change anything about fashion I would want people to wear the fantastical anytime, whenever the urge is felt, without feeling out of place or uncomfortable. I would want to put more ease into designs that are considered more suitable for special events or editorials and bring them out of that static world into a dream we can live and wear, as opposed to limiting the ethereality of certain garments to just a photo concept or special occasion.

James Oliver Langley, 22, from Southampton, England; @jamesoliverlangley

Tell us about your collection.

This wardrobe is an exploration into modern men’s tailoring, through the lens of sports uniforms and utilitarian menswear along with heavy inspiration from photographs of my fathers’ family holidays as a child. Wardrobe No. 1 consists of shirts, shorts, trousers, outerwear, denim, knitwear, and accessories. A large portion of the wardrobe is made from various weights of waxed canvas. The accessories are made from an original machine embroidered liner material.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

A curated collection of something new, while being unmistakably familiar.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

During the Covid-19 Pandemic I took time to reflect on what it means to be a designer, especially as I began my thesis collection. I realized the importance of slowing down and creating accessible designs that people outside of the industry would be able to relate to and appreciate.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I want to reinvent the art of modern men’s tailoring through designing and producing wardrobes on my own schedule instead of conforming to runway calendars and mass production.

Mina Şerbetçioğlu, 24, from Istanbul, Turkey; @minaserbet

Tell us about your collection.

My collection is a byproduct of my relationship with my home, my family, myself, and the world. Objects and feelings I’ve collected not only during the year, but throughout my life, were my biggest inspiration, and my main motivator.

I have designed a collection of clothes that I imagine being worn in the world that I have created for my alter ego: Mina Sultan. I used linen, wool, cotton, and silk [and] naturally dyed my fabrics with henna, turmeric, marigold, Himalayan rhubarb, rust, and magnets to create patterns from electromagnetic fields.

I love to create work that takes a long time to complete. The more “tedious” or laborious the work, the more it calms me. I spun my own yarn to crochet a dress with; I hand sewed an entire dress that I draped; I shaped wax and metal casted it to create my custom closures; I block-printed my custom patterns; and I needle wove on a rock to make my own button.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

The matriarch. I rule my land. A land reminiscent of Istanbul, but taken over by nature. Ancient trees bigger than gods, and more sacred…

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

The pandemic has made me realize that I do not have control over anything. I had a really hard time accepting that. No matter what happens, the world moves on, and life finds a way of going on. I create because otherwise I would just exist.

This year I approached my work very differently than I have in the past. I decided that I would create my work for my happiness and not sacrifice my happiness for my work. Whatever I felt, I really thought about what I wanted to make, and how to translate what I’m feeling into my materials. I felt very free to explore anything that crossed my mind. I used my work as an escape from the real world and a way to cope with everything happening around me. I had specific pieces in my collection that I would call “not working work,” meaning I would “take a break” but actually I would do something very calming to me such as crochet or hand sewing. These pieces ended up being the most valuable ones for me, and they hold an incredible amount of labor. I just never viewed it as such.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I would like to change the way we approach clothes. Globally we produce 13 million tons of textile waste each year, 95% of which could be reused or recycled. We need to stop viewing clothes as temporary. I would rather spend much more money on an ethically made, good quality garment than to buy many garments that are going to fall apart after being worn or washed once. This way I value that garment more and I am more likely to keep it in my closet for much longer. My aim is to create garments out of more sustainable, natural materials that people can wear for a long time.

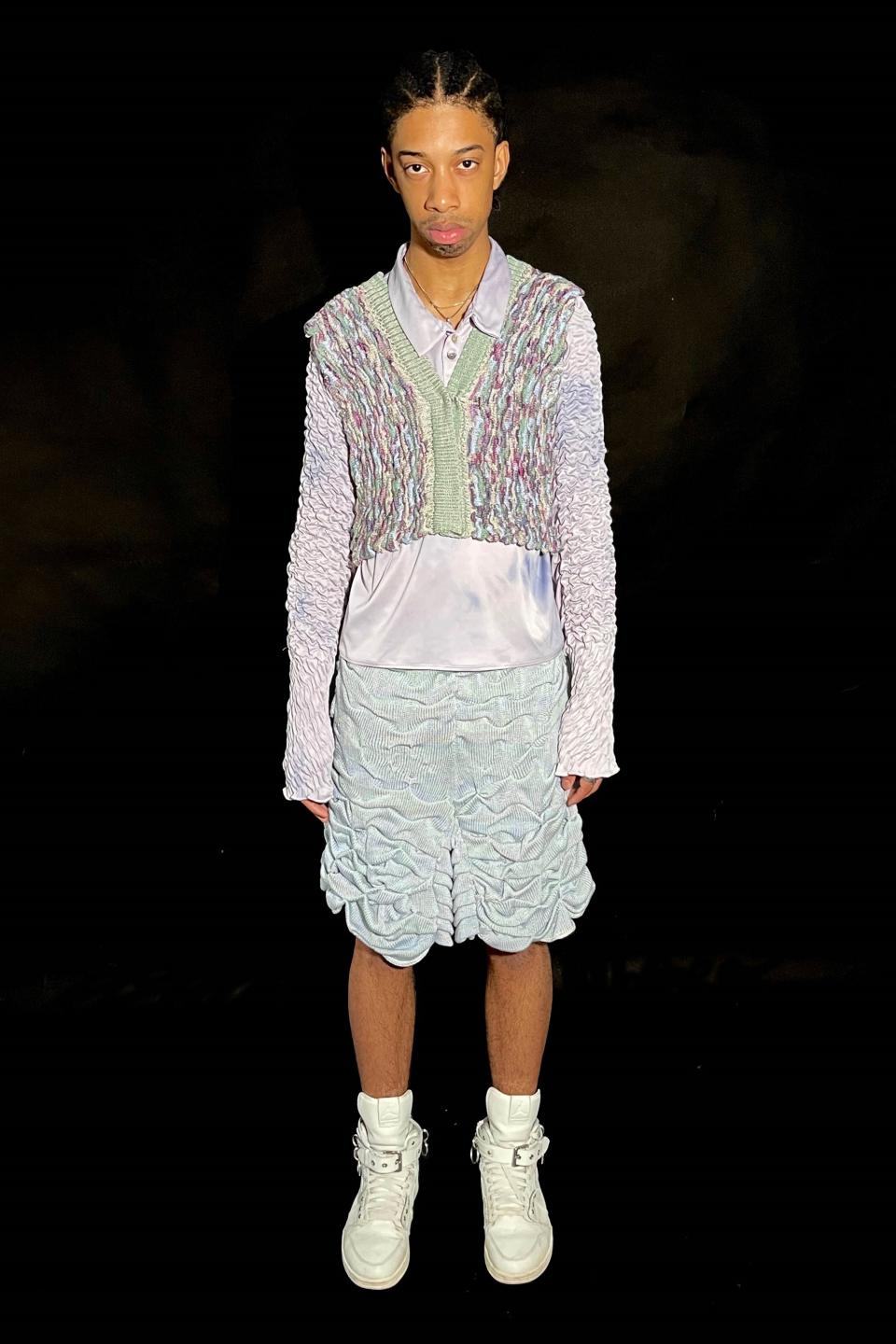

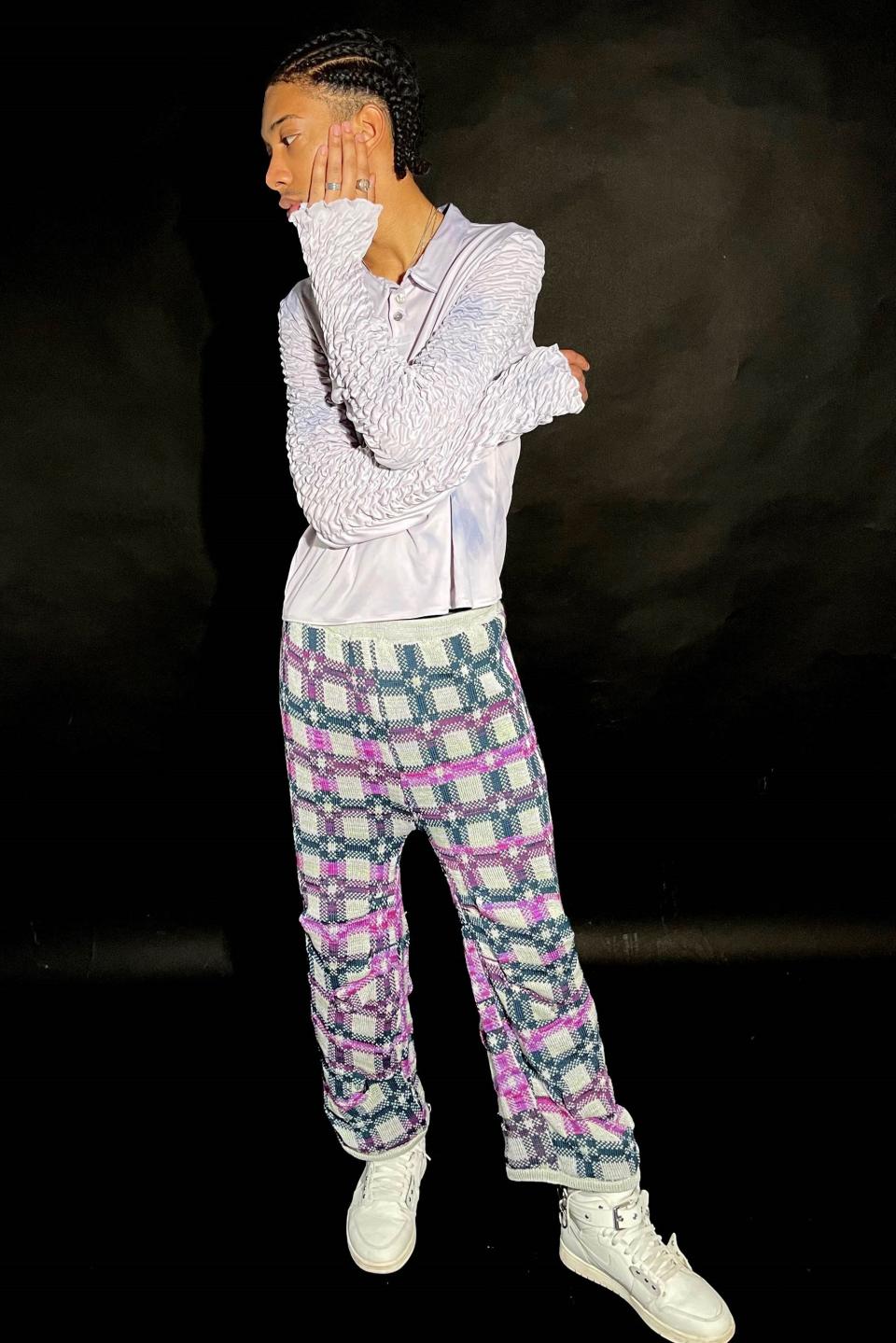

Arvi Sulovari, 22, from Midland Park, New Jersey; @arvisulovari

Tell us about your collection. I’m excited for everyone to see my knitwear and wing-like structures that I’ve patterned. Knitting is a very intuitive and emotional process for me. It feels like painting as I build up colors and textures. This way of working is so fun and expressive that it informs other aspects of my work, carrying the same spontaneous, playful energy into my draping and patternmaking. [All my knits are] made out of deadstock yarns.

[My thesis collection includes] “chainmail” knits [that] are made up of rows and rows of individually transferred eyelets on the knitting machine. [The] drippy shorts [are] machine knit [and then] I continue my intuitive process by hand sewing tacks until I am satisfied. [The] melting knit vest is made up of many vertical transfers while switching between four yarns. Essentially they are distorted stripes combined with an original punch card design, resulting in a textural look that has colors slipping in and out of each other.

The Butterfly pants [are made using] original butterfly wing patterns. There are two versions in my collection. One is track pant-inspired, made out of a nylon ripstop. The other is made to resemble a knight’s armor, made out of a shiny satin. Developing my butterfly pattern further, I created two more wing variations. Layering six wings on each sleeve, the Guardian Angel anorak’s silhouette is amplified and transformed into a more fantastical garment. It is made out of water-resistant polyester twill.

Describe your aesthetic in 140 characters.

Soft, light, sensual, romantic; yet cool and relaxed. It’s about capturing a moment of tenderness, a fantasy, and holding onto it forever.

What challenges did you face in the pandemic, and how did you overcome them?

With the whole world shaken up, all of my past plans and expectations had been thrown out the window. Nothing really mattered anymore, but in the most uplifting way. I was able to find so much freedom within myself. I didn’t have any more room for doubts, validation, or constant reassurance from my peers. I learned to be more confident in my decisions and embrace my process wholeheartedly. Like, it’s OK to have fun with your work! It’s OK for it to be a pleasurable experience. Suffering and overthinking through labor-intensive work doesn’t always mean it’s going to be the best work.

How would you like to change fashion, if you could?

I would like to see the fashion industry become more inclusive to designers and creatives whose approaches to design are more open, DIY, expressive, fine-arty. This way we can create more interesting, special, one-of-a-kind products that don’t need to be mass produced. I can already see growing confidence in independent designers and appreciation for their unique approaches to design through platforms like Instagram.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Originally Appeared on Vogue