Meet Your New Robot Co-Writer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Some art forms welcome, even require, collaboration. After all, it is the exceptionally rare film or television show that gets made by a single person. Music, too, often literally demands the assistance of others. Even in these cases, though, there is a tendency to flatten the many into if not the one, then at least the few. Films—enormous undertakings costing millions of dollars, employing hundreds of people in numerous fields—have an entire theoretical construct organized around this very flattening: auteur theory. Emerging from the French New Wave of the 1950s and epitomized by the New Hollywood iconoclasm of the 1970s, auteur theory argues that the director is the sole author of a film, or the figure to whom we should attribute the work. The notion of a single figurehead was codified in 1978, when the Directors Guild of America added a provision to its bylaws, the “One Director to a Film” rule (Article 7-208) that can only be bypassed if, as an IndieWire column put it in 2022, “director duos… apply to the union’s Western Directors Council and make the case that they are lifelong collaborators; one-offs shouldn’t even try.” Lifelong collaborators—that’s a high bar to clear.

As for the many musicians and producers and technicians that are involved in, say, writing and recording an album, the front cover still tends to credit, by virtue of its prominence, a single entity. Fans sometimes even mine famous songwriting duos like Lennon and McCartney to figure out who really wrote “Happiness is a Warm Gun” (Lennon) or “Rocky Raccoon” (McCartney). We seem prone to narrow credit down to the fewest number of creators possible, despite what the bylines say.

But what of literature? Creative literary art forms, particularly fiction and poetry, are inherently solitary pursuits. There is nary a legacy of prosperous partnerships, and almost no tradition at all of enterprises with more than two authors. There are—of course—exceptions (some of which we’ll get to), but think of it this way: How many classic novels are written by more than one writer? How many collaborative novels have you read? How many are taught in schools? How many can you even name?

More importantly: why is this the case? Why aren't there more literary collaborations? To be sure, in fantasy, science fiction, romance, horror, and mystery, there is a much stronger history of partnerships, but less so in so-called literary fiction. Novels written by groups are rare in any genre. In literature, we venerate the one over the many, and while it’s tempting to explain this away by citing the solitary nature of the practice—or, perhaps, the singular voice written texts seem to represent—I would posit that writing is not, nor has ever truly been, a wholly solitary act, and that collaboration occurs way more often than we like to admit or can even consciously acknowledge. But this tradition of encouraging solo art over teamwork—which in the past has led to the industry of ghostwriting and to numerous incidents of plagiarism—now has a new, fiercer, and much more insidious unintended consequence: the inevitable rise of fiction co-written by AI, and the flattening of literary storytelling.

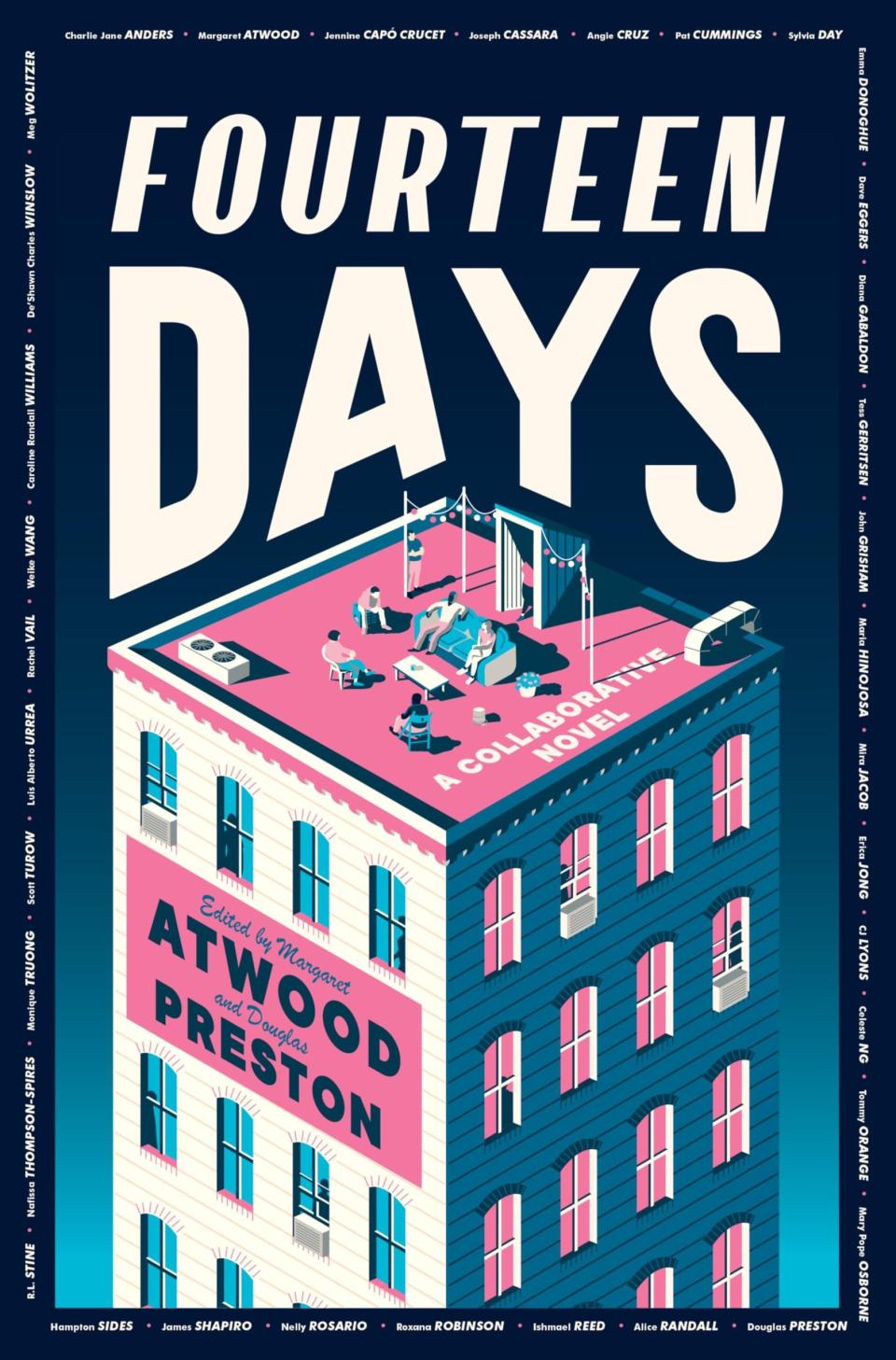

I ask these questions because of the publication of Fourteen Days, a novel written by 36 authors ranging from John Grisham and Erica Jong to Tommy Orange and Nafissa Thompson-Spires. The project was overseen by Margaret Atwood and Douglas Preston, who both also contributed. Supported by the Authors Guild Foundation, Fourteen Days tells the story of a new superintendent of an apartment building on Rivington Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The place is called the Fernsby Arms, which the super describes as “a decaying crapshack tenement that should have been torn down a long time ago.” The super tells the reader to call her 1A, an Ishmael for our journey through Covid, for as soon as 1A begins her job at the Fernsby Arms, which features “rotten” pay and a dingy basement apartment, the pandemic hits. The previous super lets 1A in on a little secret: the super can access the roof of the building, which provides her with stunning views of the emptied city. She hopes to keep her rooftop oasis a secret (for legal reasons), but soon the tenants discover this pocket of paradise. In the boredom and isolation of quarantine, they begin to connect with each other by telling stories. Fourteen Days is a kind of a miniature Decameron for this unsteady decade.

amazon.com

$28.99

The stories alternate between humorous and poignant, personal and historical, dark and light. There’s an added component of wondering which of the 36 contributors wrote which part, a game I recommend readers not spoil by consulting the authors’ bios in the back of the book, where the contributions are itemized. It’s fun to try to link a story to its teller. Sometimes it's obvious: I figured that James Shapiro, author of Shakespeare in a Divided America and The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606, wrote the section about the Bard’s own encounter with a pandemic, but R.L. Stine’s brief addition wasn’t as easy to sniff out (though one fact should have clued me in). The Covid stuff—the uncanniness of empty streets, cheering for essential workers, toilet paper shortages, newly acquired hobbies—will affect each reader in their own way, but as for me, I didn’t particularly love being back in that atmosphere of novelty and monotony.

What struck me most, though, was the novel’s self-reflective theme of collaborative storytelling. The characters share themselves with each other through narrative. Art, for the tenants of Fernsby Arms, is a tool for digging out tiny seeds from our souls and dispersing them with the hope of welcoming soil. They begin as types, because the previous super conveniently left a dossier of psychological-by-way-of-pop-cultural diagnoses of every tenant, replete with snappy nicknames like Eurovision, the Lady with the Rings, and Merenguero’s Daughter (which is explained away because he was “an amateur psychologist,” whatever that means, and not because he was an invasive creep). As the days pass and tales are told, they emerge from and complicate those initial impressions, their ever-finer definitions written by the stories shared and the connections forged. Fourteen Days, in this sense, can be seen as a celebration of working together—of the surprising and wonderful things we find when our ideas collide with others, how much that aids in our development, our betterment, and how, finally, those individual improvements can amass into a stronger society.

What Fourteen Days is not an argument for, however, is the beneficial results of literary collaborations (particularly group collaborations) as an artistic experience for readers—which is to say that as a whole, Fourteen Days is really bad. The best parts are, not surprisingly, some of the fascinating and idiosyncratic stories from the tenants—meaning the parts in which the uniqueness of a contributor shines through. Perhaps Douglas Preston is to blame, as he is the one credited with the “frame narrative,” which is just ghastly in its inept and quite irritating conclusion. One doesn’t envy Preston’s daunting task, though his is perhaps less enviable than the person who should have told Preston or Atwood or the Authors Guild that maybe someone else would make a better narrative framer.

There is no doubt that the 36 writers whose names crowd the perimeter of the novel’s cover very likely found the experience of creating Fourteen Days to be fun, interesting, enlightening, profound, and instructive. Indeed, Fourteen Days is a portrait of, as well as an argument for, the vitality of collaboration. But there is also no evidence here that the greatness of individual writers is usefully mixable—somehow the math of literary creation functions inversely, where the higher the number of each factor in an addition or multiplication problem, the smaller the solution will be.

There are numerous examples of group fiction writing, but with the exception of entities like Alice Campion, a pseudonym for a team of Australian fiction writers who aren’t established individually, most group-written novels have either failed as an enterprise or were conceived as literary stunts. In 1969, an erotic novel called Naked Came the Stranger entered the New York Times Bestseller list. Though credited to Penelope Ashe, the book was really crafted by 24 journalists, mostly men, led by longtime Newsday columnist Mike McGrady, who viewed the popularity of novelists like Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susann as an indictment of literary culture, believing that any book would be a bestseller if there was enough sex in it. When the hoax was revealed, the novel’s sales rose.

In the early 2000s, a bunch of sci-fi authors created Atlanta Nights, a deliberately terrible novel, in order to show that PublishAmerica, a vanity press claiming to be a legitimate and discerning publisher, would accept anything submitted to them. And I mean anything: there were missing chapters, sections that were repeated word for word, laughably poor spelling, and a senseless plot. PublishAmerica did indeed accept Atlanta Nights for publication, but the authors revealed the prank and declined the offer, their point sufficiently made. Even the people behind Alice Campion have ulterior (though kinder) aims, inasmuch as they use their success to promote their brand of collaboration, even going so far as to publish an instructional volume called How to Write Fiction as a Group. Similarly, Ken Kesey once produced a novel with students from his writing workshop. Entitled Caverns and attributed to O.U. Levon, the story revolves around Charles Loach, a man recently released from serving a prison sentence for murder. He’d killed a man who threatened to reveal the location of caves featuring archeological treasures that were sure to make Charles filthy rich. In Caverns, we see Charles’s journey to find those ancient drawings. As interesting and at times compelling as the novel is, it exists seemingly only to prove that such an undertaking can be completed, not necessarily completed exceptionally.

amazon.com

$16.94

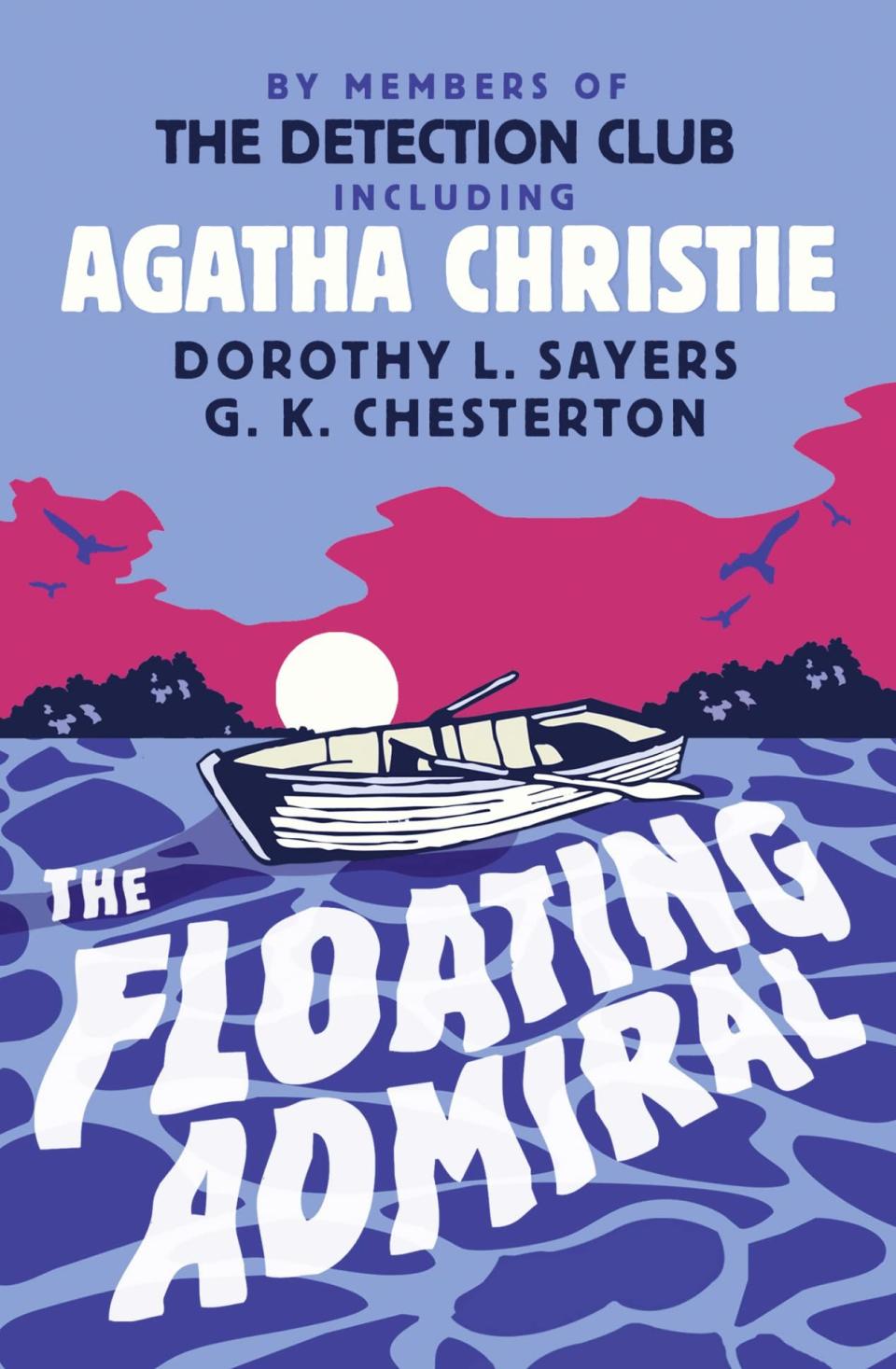

These examples were written with some kind of pragmatic goal in mind: promoting teamwork or satirizing literature. Sometimes, however, collaborative novels are produced merely for the sake of enjoyment. In the early 1930s, a cabal of English detective novelists (including Agatha Christie, G.K. Chesterton, and Dorothy L. Sayers) formed The Detection Club, and together they produced a few mystery novels. In the first one, The Floating Admiral, the club assigned Chesterton the prologue, Anthony Berkeley the finale, and everyone else a single chapter; then, they set out to compose the novel chronologically, with no fixed plan. They established rules (such as, according to Sayers’s introduction, “each writer was bound to deal faithfully with all the difficulties left for his consideration by his predecessors”) and followed parameters the club believed were required in classic whodunits (such as, again Sayers: their “detectives must detect by their wits, without the help of accident or coincidence”). The result is a work in which you can see that, as contributor Simon Brett notes in his foreword, “the writers involved in The Floating Admiral enjoyed the intellectual challenge that faced them.” While this sense of fun is palpable, the novel is not better than any of the individual writers’ other books.

The problem can be put this way: the act of collaborating is rewarding and enriching for the collaborators, but the results don’t usually hold up against the standard set by singular voices. As such, there is an enormous gap between the value of the act and the merit of the result. This divide has become newly relevant as our notions of what it means to collaborate, as well as our fixation on individual achievement, are now up against a force, a tool, and a readymade collaborator in artificial intelligence. And if we don’t amend our concept of human-to-human aesthetic cooperation, then we will potentially face an era of more collaboration, and yet somehow less uniqueness.

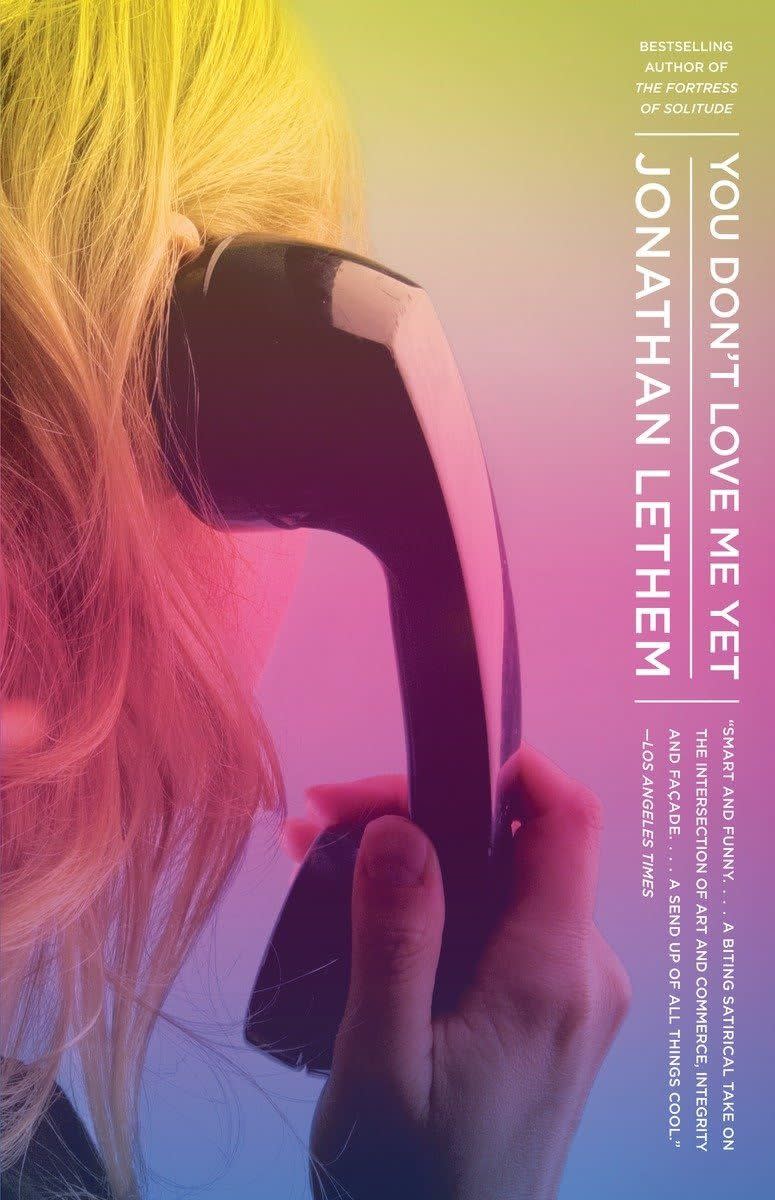

“This is an issue that’s very alive in our culture,” Jonathan Lethem told an audience at Google’s headquarters in 2007, “precisely because of the pressure that technological change has put on the operations of cultural materials and cultural practice.” The occasion for Lethem’s talk was his frothy comedy You Don’t Love Me Yet, a novel about the mysterious alchemy of creative collaboration. The rock band at the story’s center can’t clearly trace the origins of their latest songs, which have catapulted them into stardom. The confusion begins when the bass player incorporates her boyfriend’s words into the band’s lyrics, which in turn reinvigorates the singer’s creative drive, which then inspires the rest of the band. Who, then, is responsible for this fertile period? The impetus is the boyfriend’s words, but they weren’t written to be sung, or, for that matter, with any audible presentation in mind. So would his name need to be credited in the liner notes? Or is his role in the band merely happenstantial? And what happens when this person demands to share in the profits?

amazon.com

$16.00

Lethem referred to You Don’t Love Me Yet as “silly,” “irritatingly flippant,” and “typically fizzy,” while also containing “within it a sort of allegorical argument about intellectual property, about creativity and ownership." In this novel, he’s interested in how, in an environment fraught with legal ramifications over originality, plagiarism, copyright, and the “anxiety” of influence, “artists are persistently beguiled into exaggerating—to themselves first and then to others—the solitary, original, iconoclastic nature of their practice, which is in fact, so often, at the edges at least, or at the edges of consciousness at least, one that depends on borrowing, influence, collaboration, pastiche, collage, appropriation.” Acknowledging the myriad contributors to and influences on one’s artwork is one thing; including their names with yours on the album art, or the book cover, or the movie poster, is quite another.

But why? If I am responsible for 99% of a finished piece, can I truly claim to be the sole creator of that piece? What about 82%, or 68%? When does it become dubious—or even unethical—to contain the numerous co-authors under the umbrella of one? Some might argue that these issues are essentially legal ones, as abstractions like “credit” are less about actual attribution than about profit-sharing and royalties, which result more from agreements made by the creators than honest accounts of their creations. But what if the situation were not a handful of people’s work being left out of the credits? What if it was something like hundreds, thousands, millions of contributors’ work not only going unacknowledged, but in fact remaining impossible to detect in a creation ultimately credited to no one?

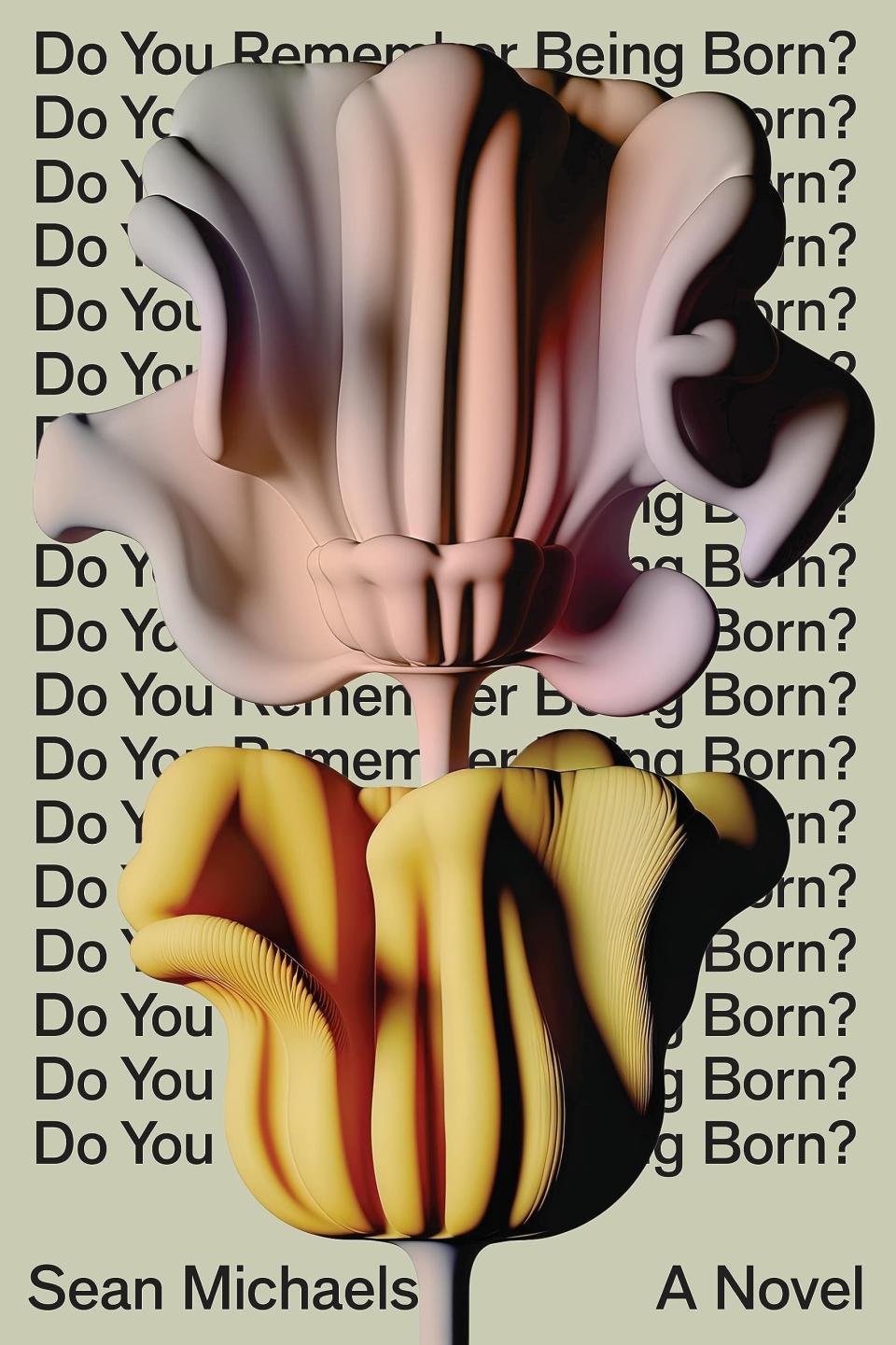

Sean Michaels’s lovely and thoughtful novel Do You Remember Being Born? tells the story of a septuagenarian poet named Marian Ffarmer [sic], who accepts an offer from a major tech corporation to co-write “a long poem” with their artificial intelligence, named Charlotte. “Charlotte’s been trained,” Marian is told by an employee, “on a massive data set of poetry books and journals, on top of a basic corpus of ten million web pages. Two point five trillion parameters…”

Marian’s experience with the AI oscillates between awe at the poetry bot’s ingenuity and dismay at its algorithmic approximation of meaningful expression. At first, Marian can “taste the disjuncture between our lines, like chalk and cheese,” but then something changes, though Marian recognizes how difficult such shifts can be to accurately diagnose:

The software learned me to some degree, or I learned it, or else nothing changed at all except my posture toward its work: that instead of awaiting an obvious fit, hook and eye, I anticipated that band of friction, as a spade awaits the dirt.

The novel takes its time deftly and tenderly interrogating the nature of meaning, the inexhaustive dexterity of language, and our knack for finding thematic or linguistic connections where none were intended. Marian’s generosity and curiosity provide her with an openness about Charlotte’s literary abilities, while her intelligence and expertise refuse to permit mediocrity or meaninglessness. The delicate drama at the novel’s core comes from this complex inner conflict.

The conversations between Marian and Charlotte are written; Marian types into Charlotte’s software and hits the Proceed key. Marian’s typed side of the exchange is rendered in a unique font, while Charlotte’s responses are highlighted in gray, which usefully differentiates between the two and visually reinforces Charlotte’s fabricated isolation: Charlotte is literally kept in dull, slate boxes. But it performs another function: what does it mean when those gray highlights appear not in scenes featuring Charlotte, but moments in Marian’s personal life? In the novel, it’s a hint that Marian might eventually collaborate with Charlotte (or another AI) on more than just this one assignment.

But in the acknowledgements, Michaels provides the other motive behind those gray highlights, which pop up more and more as the novel progresses: the poetry that Charlotte writes and all those other gray sections “were generated with help from OpenAI’s GPT-3 language model as well as Moorebot, a custom poetry-generation software that I designed with Katie O’Nell.” Moorebot, as the name suggests, is based on the complete works of Marianne Moore, a modernist poet and critic of exacting profundity. Marian is also based on Moore, who famously was asked by Ford in the 1950s to come up with a name for their newest car; among her suggestions were “Utopian Turtletop,” “Pastelogram,” and “Magigravure.” Needless to say, Ford did not choose any of Moore’s submissions (although the name they ultimately chose, Edsel, is really no better and played a role in the car’s spectacular failure).

amazon.com

$13.50

Michaels, then, has done what I attempted to do as I read Fourteen Days. He literally highlights every single contribution from his AI collaborators, down to single words. I should appreciate his thorough transparency, as I now know precisely what to give him credit for. But instead I found this information disconcerting, as if somehow those passages were less credible, less deserving of praise. For obvious reasons, it’s appropriate that Michaels used AI for Do You Remember Being Born?, and it’s to his credit that he isn’t obfuscating his process. Moreover, Michaels used a custom AI bot for his purposes, one that he had a hand in designing. Most future users of AI won’t be so forthright or considerate.

Jacob Ward’s The Loop: How Technology Is Creating a World Without Choices and How to Fight Back argues that the recent explosion in AI presents us with daunting problems and potentially disastrous consequences. One major issue is the source of these new AI bots: “Once upon a time,” Ward writes, “this sort of world-changing technology was developed by academic institutions, national labs, the Department of Defense. Today, AI is being refined entirely inside for-profit companies. It’s built to make money.” Yet the marketing around popular iterations like ChatGPT or Midjourney emphasizes the ease with which it can manifest your heretofore unrealizable artistic visions, as if the idea for a piece of art were identical to its implementation. Despite our theories to the contrary, capitalism does not engender healthy competition for the better product, but instead it incentivizes cutthroat bottom-lining from workers’ pay to the quality of the materials. Capitalism is simply about which corporation can earn more, not which one deserves it. What, then, truly motivates businesses to make the best, most ethical AI when it’s much more lucrative to obscure the sources of the bot’s intelligence and focus on its efficiency?

The trouble with this is that many non-tech companies hire out the same AI services that everyone else uses, so that, as Ward puts it, “the same pieces of machine learning are being deployed on everything.” Sean Michaels made his own AI bot out of texts germane to his novel, but that is not the future capitalism wants. They want as many people using the same few brands as possible—the same paradigm we have with cell phones, computers, cars, food, TV networks, movie studios, record labels, &c &c &c. Collaborations with AI will have similar cultural weight as other easily makeable, quickly deployable, endlessly reiterative, and ultimately disposable media like memes, posts, reels, TikToks, and tweets, which suffer in our critical estimation because of their bare ingredients and simple, dashed-off construction (those are also somehow the same reasons they’re so ubiquitous and engrossing). But if the presence of AI in a task commonly seen as uniquely difficult, like writing a novel, becomes undetectable and is allowed to remain uncredited, will these algorithms—from only a handful of corporate entities—flatten or dilute our creative output without us realizing quite why? And if AI is supposed to be trained on texts produced by people, so as to continually evolve its understanding of human nuance, what happens when a glut of novels containing unacknowledged contributions from AI enter its memory? Won’t that flatten our creativity all the more?

Beyond the potential uniformity, there are ethical considerations in addition to the accusations of theft and plagiarism that rightly follow AI everywhere it goes. AI’s decision-making has repeatedly been shown to display the same biases and shortsightedness as its creators, but its sheen of objectivity and its prolific usage concretizes those unconscious tendencies into systemic rules. If this technology is unable to distinguish between correlation and causation, if it perpetuates racism, sexism, and bigotry generally, then why wouldn’t its suggestions for narrative or characterization be equally as compromised? With that in mind, how can we possibly trust AI as a literary collaborator?

The novel is a form of extreme and elaborate nuance. Its most celebrated practitioners locate the parts of ourselves that we recognize, but don’t understand. They mine the mysterious and mischievous and melancholic for keen insights on the intensely particular. Their characters act rashly, irrationally, inexplicably, and with an eye toward self-destruction. How will a secretive, profit-driven, pattern-finding, content-stealing piece of software genuinely add to this form? This form that isn’t interested in answers or definitions or predictable behavior?

We are going to find out, whether we want to or not.

We have created an environment where we promote solitary creativity, despite the fact that collaboration is in everything we make, even if it’s unacknowledged. Rules and regulations warn off plagiarism, schools entreat us to do our own work and intimate that working together is a kind of cheating, and generally our culture has an unhealthy fixation on Great Individuals. But how do we learn, if not from others?

A novelist learns what a novel is by reading them, which means the happenstance of those initial selections loom over their entire career, usually invisibly. Art as a tradition depends on historical collaborations, calls and responses over years, decades, centuries—art in conversation with other art, emerging forms contrasted with old ones, the myriad manifestations of inspiration, competition, and influence. Nothing is achieved alone. Autodidacticism is a myth, because nothing you have ever learned is learned without the assistance of someone else: the teacher, the friend, the parent, the author, the publisher, the lover, the person who built the road that leads to that historic tomb, the person who built the kayak you used to investigate that bioluminescent lagoon, the one who inspired you to try to learn in the first place, or the millions of people who concocted a language in which you express a realization. Life is collaborating with us all this time, in all these ways, but we just refuse to give it credit.

But because, as Lethem said, we’ve been goaded into overstating “the solitary, original, iconoclastic nature” of our art-making, we’ve created the perfect environment for AI to step in and collaborate with writers while still maintaining the illusion of wholly individual effort. Ghostwriters have served this purpose up until this point, but they are at least still people with all the idiosyncratic picadilloes that come with personhood. An AI ghostwriter may provide a quick solution, but it can never match the eccentricities of those uncredited collaborators in our lives: our crazy families, annoying coworkers, lifelong friends, random passersby. Each one capable, inadvertently or not, of helping solve a creative problem, their personalities and motivations ranging from supportive to combative. With AI’s insidious threat to the novel, the larger effect, I fear, will be the diminishment of literature’s most complex, sophisticated, and enriching form, which, at its best, reflects back to us our wondrous and bewildering richness. If our novels stop being complicated, deep, or insightful, will that mean that we’ve stopped being those things too?

What if we reevaluated our concept of collaboration? If we saw how often we engage in it, how vital it is to good living; if we reconsidered our stringent attitudes toward credit, attribution, and ownership; if we weren’t so ready to dismiss group work just because the examples we’ve got aren’t exactly testaments to its efficacy; and if we encouraged communal participation as much as we promoted individual maturation, we might see that we don’t need AI to help us tell interesting stories, at least not until we run out of our own. As Fourteen Days puts it in the novel’s conclusion, a succinct distillation of both their project’s guiding philosophy and this essay’s despairing entreaty: “There were so many, many more stories.”

You Might Also Like