Meet Philip Anschutz, the 'Secretive' 'Anti-Trump'

Many Americans believe their country is run by people they have never heard of, and in the case of Philip Anschutz, they may be correct. Anschutz is an ordinary-looking 77-year-old resident of Denver who happens to be one of the richest men in America, and a most enterprising one at that.

If you’ve been to a concert recently by Taylor Swift, Kanye West, or Justin Bieber, you put money in his pocket. If you’ve been to Yellowstone National Park, Mount Rushmore, or the Grand Canyon, your dollars likely found their way to him. Chances are you’ve heard of the basketball team he co-owns, the Los Angeles Lakers, or the railroad he used to hold, the Southern Pacific. It’s possible that today you will start the morning by reading one of his newspapers, drive to work in a car fueled by oil from one of his wells, and at night catch a Hollywood blockbuster he produced in one of the hundreds of movie theaters he owns, followed by a T-bone raised on one of his ranches.

Anschutz's low-key style has earned him the moniker 'the anti-Trump.'

Who knows, you might be paying him rent as you read this; Anschutz is currently the 22nd-largest individual landowner in the United States,with exceptionally large holdings around Los Angeles and in Colorado.

Don’t be embarrassed if you don’t know his name, though-Anschutz doesn’t want you to. “That’s not important,” he’s likely to grumble if you ask about the personal ambitions that led him to build one of the greatest fortunes in the history of the west. “I don’t want to talk about that. Let’s discuss something else.”

His tone is cordial but firm. Anschutz is used to deflecting attention; over 30 years as, arguably, the most prodigious American entrepreneur since J.P. Morgan, he had, until the morning we sat down with him, never given full-length interview to the press.

Not that he is averse to publicity (for the right reasons) or reclusive (anyone who wants to find him can, with a little Googling.) In the Denver area, where everyone seems to have a story about meeting him in person, the Anschutz name adorns both an art museum and the largest university health complex in the Rockies.

Like Warren Buffett, another multibillionaire from the middle of the country, Anschutz is known to go to bed early, drive his own car, and take a dim view of loudmouths and egomaniacs. (Anschutz's low-key style has earned him the moniker "the anti-Trump.") Also like the Oracle of Omaha, Anschutz has strong political views that he is not afraid to put his money behind, thus ensuring the disapproval of a certain sector of the population.

Even his critics have a hard time mustering outrage against him, though. A front page New York Times profile devoted to the “web of ties” between Anschutz and his longtime lawyer, Neil Gorsuch, whom President Trump has nominated for the Supreme Court, called Anschutz “secretive” but otherwise found little to criticize. “About the worst thing anybody says about [Anschutz],” Los Angelesmagazine once wrote, “is that he’s cheap.”

All of which raises a question: Say you were 77 years old, a grandfather, and a businessman with a reputation for “seeing around corners.” You had already made more money than God, reshaped major cities, pioneered industries, donated more than a billion dollars to charity, and earned the kind of influence that makes senators crawl across the country on their knees. What would you do for an encore?

There are 295 historic hotels in the United States, as judged by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Some are world famous, such as the Waldorf Astoria and the Plaza in New York. Others, such as the Greenbrier in West Virginia and the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island in Michigan, are recognized national treasures, if not household names. All are at least 50 years old, and a great many were once owned by characters as unusual as the properties themselves.

Today that is less and less the case. Hospitality chains and private equity firms increasingly stand behind the most illustrious brands, such as the Pierre (current owner: the Tata Group, the Mumbai-based multinational that purveys everything from phosphoric acid to Tetley tea) and the Waldorf (owners: China’s Anbang Insurance Group, which plans to convert part of the icon into condominiums.)

“The world is full of nice hotels, but it is not full of great hotels,” Anschutz says.

While big corporations do many things well, upholding the uniqueness of palatial hotels that frequently began as labors of love and whose high-touch service model depends on eschewing a bottom-line mentality isn’t one. As a result, while places like the Waldorf and the Pierre have managed to survive in today’s efficiency-driven age of hospitality, devotees of the great hotels mourn a plague of corporate soullessness and ROI-obsessed management spreading from one gilded lobby to the next. There is even a group of hotel executives whose occasional meetings have become a kind of group therapy session where members grieve over the latest sterilizing renovation.

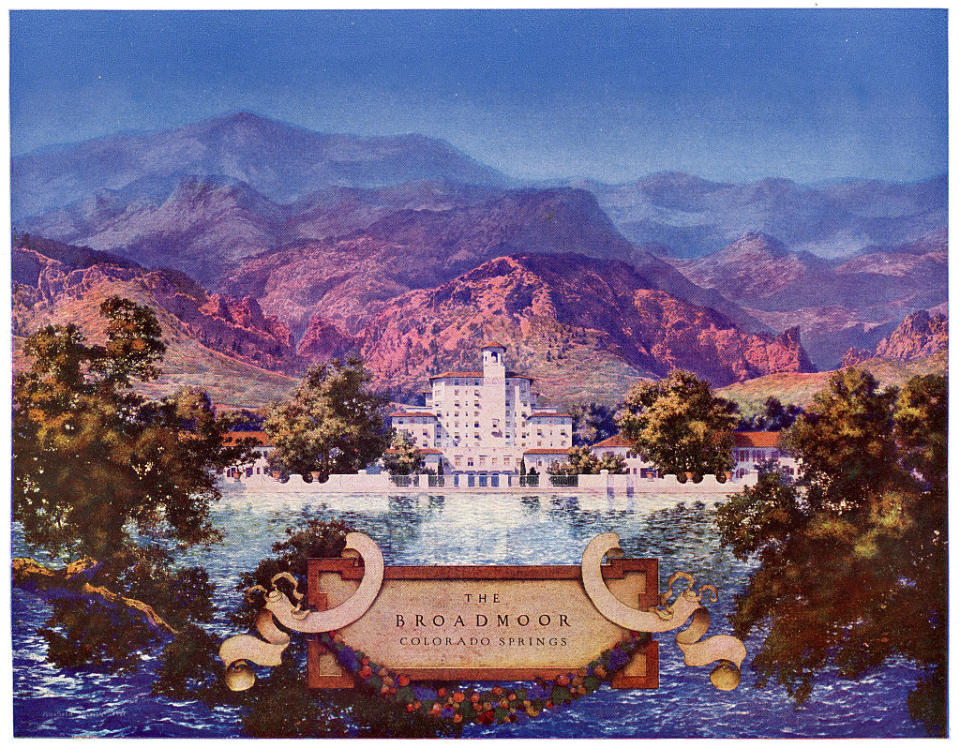

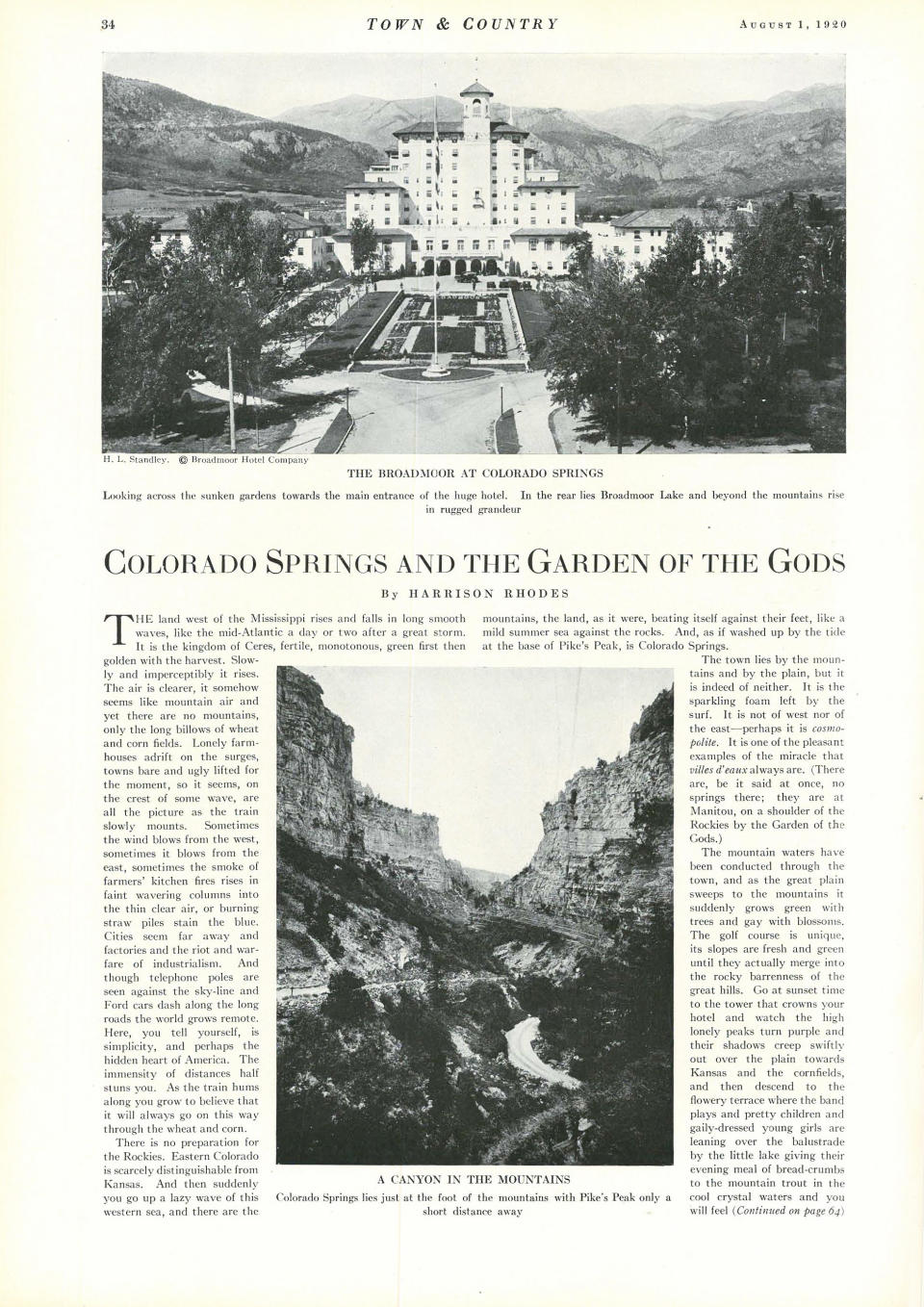

Philip Anschutz stayed at his first great hotel at age five, just after the Second World War. His father, a Kansas oil driller, liked to bring his family to the Broadmoor in Colorado Springs, known as the most glamorous hotel between the Waldorf and the Fairmont (current owner: also Anbang), with its polo grounds, celebrity clientele, and campus designed by Frederick Law Olmsted surrounding an Italianate château (built by imported Piedmontese artisans) in the shadow of Pikes Peak. At dinner one night when he was 10, Anschutz declared his intention to buy the hotel, though at the time his family could afford only a short visit.

Over the next 40 years the Broadmoor managed to avoid the fate of other grand hotels (particularly those in low-glitz destinations like Colorado Springs) as it was owned by a charity with an unusual mandate: to preserve the superior service and eccentric traditions of a luxury hotel. Since then it has been the only hotel in the country to receive top rankings from both AAA and Forbes every year, going back some four decades.

However, in 1988 the 784-room resort was purchased by Oklahoma Publishing, a conglomerate with interests in amusement parks and convention centers, which focused on building a gated residential community ancillary to the hotel. The Broadmoor’s guests subsequently observed a certain raggedness creep in, none more attentively than Philip Anschutz.

“The world is full of nice hotels, but it is not full of great hotels,” he says, sitting in a windowless executive suite under the lobby of the hotel and looking mogul-like (for once) as he chews on an unlit cigar. Although “hardly a week goes by that I don’t get opportunities to buy a hotel,” he says, only what he calls “special assets”-hotels with history, character, and a sustained legacy of focused reinvestment by the ownership-interest him. His list of greats includes only three: the Broadmoor, the Breakers in Palm Beach, and Sea Island in Georgia.

Anschutz made his fortune in oil in Wyoming in the 1960s, following in the footsteps of his father. He then went into railroads, followed by telecommunications and entertainment. In 1984 Forbes ranked him the seventh-richest man in the U.S.; last year he fell to 39th.

A decade ago Anschutz returned to his wildcatting roots when he decided to convert a 500-square-mile cattle ranch on the high plains in central Wyoming, one of the windiest parts of the country, into a wind farm that will eventually host 1,000 turbines the size of jumbo jets. Currently inactive as it awaits government approval, it will be the world’s largest wind farm when it opens, an energy source four times as powerful as the Hoover Dam, able to fulfill the electricity needs of San Francisco and Los Angeles combined.

Around this time Anschutz repeatedly offered to buy the Broadmoor. A history buff, particularly of the American west, he was driven by the model of Spencer Penrose, the scion (or perhaps anti-scion) of a prominent Philadelphia family who, after graduating last in his class at Harvard in 1886, came out west and founded several of the most profitable gold and copper mines of the 19th century. Famously hard-living, Penrose owned the country’s second-largest private supply of liquor during Prohibition, as well as a fleet of race cars.

“He was known for three things: women, drinking, and fighting,” Anschutz says. “Apparently he was good at all three.” Anschutz, by contrast, has been married for 50 years, rarely drinks, and has been spotted driving himself in a rented Ford Taurus.

But Penrose had “a way of seeing how things fit together,” Anschutz says. The 1920s were the golden age of American hotels, marked in New York by the opening of the Sherry-Netherland and the Carlyle (and, not long afterward, the relocated Waldorf Astoria). Hotels, according to the authors of Grand Hotels of the Jazz Age, had become not just inns for the well-to-do but “arbiters of style and stages upon which to display wealth.” As Henry James wrote, “One is verily tempted to ask if the hotel-spirit may not just be the American spirit most seeking and most finding itself.”

Penrose wanted his own palace out west and decided to build the Broadmoor, with a design by architects Warren & Wetmore, the team behind Grand Central Terminal and many other New York landmarks. “To build a European-style resort in Colorado Springs in 1916 took vision and nerve,” Anschutz says, requiring, at one time, the employment of 100 workers for every two guests. In fact, the hotel, despite attracting such luminaries as Marlene Dietrich and John D. Rockefeller, never made money under Penrose.

Doing so nowadays may be even harder. “Following the recession of 2009, there has been a tremendous amount of investment in the hotel sector and the luxury sector,” says Paul Leone, CEO of the Breakers. “The market has been hot, and there has been pressure for owners to sell because they could get significant prices, and also because of a consolidation by the private equity hedge funds, private equity public companies-all the way up to Hilton, Marriott, and Starwood. That pressure, in terms of pricing, has made it hard for independents to compete.”

Anschutz is one of America’s most generous philanthropists-in 2013 he gave away $50 million, much of it to public and charter schools. Accurate estimates of his charitable giving are hard to come by (his philanthropic work is so discreet that the $1 billion Anschutz Foundation does not have a website), but according to the Philanthropy Roundtable, he and his wife Nancy have given money to “orchestras, museums, churches, schools, women’s shelters, rehab clinics, the Boy Scouts, the Salvation Army, and programs that serve the underprivileged community. They have launched public service campaigns and anonymous programs to meet small but emergency short-term needs of the truly needy.”

“The industry has become the real estate business more than the hospitality business."

That said, making money is something Anschutz takes seriously, and the Broadmoor, he says, “must operate at a profit, as you cannot have any business venture, no matter how well-intentioned, and especially not a long-term one, that does not have a firm financial foundation.” Yet one way to get the reticent billionaire to open up is to trigger his disdain for the sort of opportunistic, asset-hoarding private equity firm that sees only profits and losses.

“Properties like the Broadmoor diminish greatly in number over time,” he says. “They flourish best if owned by a family with the values of stewardship, as opposed to seeing them as just another asset. The Jones family at Sea Island was one of those families. The Penroses were another, and there’s a third, the Flaglers and their heirs at the Breakers.”

Of course, family ownership of a business brings unique problems. Spencer Penrose, ever the bon vivant, did not have heirs. Other hoteliers have produced too many, leading to succession battles and fractious ownership.

In 2011 Oklahoma Publishing finally agreed to sell Anschutz the Broadmoor for a reported $1 billion. Knowing his dedication to the resort, its executives rejoiced, yet few imagined what would actually happen.

I’m standing 1,000 feet above a roaring river, toes curled over the edge of a platform no bigger than a queen-size bed, as I talk my legs into joining the bald eagles soaring beneath us. In a few moments my life will depend on a galvanized steel cable the width of a finger, as I soar across a box canyon half a mile wide, and what amazes me most about this is not that I am one of the first people to try out this ride but that the people who went on its inaugural run, barely a week ago, were six U.S. senators. (A seventh declined the offer.)

The zipline hangs over Seven Falls Canyon, a narrow roseate gash in Cheyenne Mountain that was one of Colorado Springs’s main tourist attractions until four years ago, when historic rains flooded South Cheyenne Creek and destroyed the road leading in. Anschutz approached the canyon’s longtime owners, a Colorado Springs family, and two years later the Broadmoor owned an attraction that would not be out of place in a national park, just five minutes from guests’ rooms.

After riding across the canyon at 45 miles per hour, I was approached at dinner by Anschutz. “Were you nervous?” he asked. (I was.) Chuckling, he admitted that sending senators across it had made him nervous, too. “I didn’t want to lose the Republican majority,” he said.

Anschutz has been labeled a conservative Christian, but he reportedly stopped attending church a decade ago and calls himself merely “spiritual.” In a sense his true religion can be found atop Cheyenne Mountain, where Spencer Penrose built a mountaintop retreat with views across the Great Plains in one direction and of the Front Range of the southern Rockies in the other.

Abandoned for decades, the lodge, now called Cloud Camp, has been painstakingly remodeled and filled with paintings by Charles Schreyvogel, Albert Bierstadt, and Frederic Remington-the Picassos of American western art, of which Anschutz is the world’s leading collector. Judging by the paintings in the lodge, to which he often makes the seven-mile hike early in the morning, Anschutz has a taste for the dramatic-the genre’s stock in trade, of course: war parties, forced marches, buffalo hunts, and other depictions of conflict and bloodshed along the frontier. He believes the west brings out the best in human nature as well as the worst.

In some ways that drama isn’t over. Denver is America’s fastest-growing large city, its economy fed by booms in technology and a certain formerly illegal recreational drug. It also has cutting-edge infrastructure created-at great profit, of course-largely by Philip Anschutz.

The recent economic surge touches all corners of the state, including Colorado Springs, where Anschutz has made major investments beyond the Broadmoor, buying the local newspaper, an arena, and land throughout the city. Meanwhile, along with the canyon and Penrose’s mountaintop aerie (where rooms now rent for $975 per night), he has added a fishing camp on a fabled trout run, the Tarryall River, an hour to the west. Anschutz declines to reveal how much money he has plowed in, but estimates reach $500 million.

Moreover, the resort is now owned by an unusual 100-year family trust, in order to make sure the Broadmoor does not fall victim to “the wrong kind of owners.” Asked to elaborate on the qualities that make an owner wrong, he demurs.

“The industry has become the real estate business more than the hospitality business, and more and more owners are looking at these as real estate deals,” says Paul Leone of the Breakers. “They’re not looking to be operators over the long haul. The right owner is someone with a very long-term perspective. The wrong buyer is someone looking to flip the property rather than hold on to and take care of it.”

Anschutz calls his outlook "thinking of yourself as a steward rather than an investor," a remarkable statement coming from a man with one of the most stupendous records in American history for turning a profit, and one who has just spent upwards of $2 billion on a pair of hotels.

Sea Island, on the coast of Georgia, was built during the great hotel boom by Howard Coffin, an automobile tycoon. Sprawling, verdant, and isolated, the resort features five miles of uninterrupted coastline, one of the best hunting preserves in the South, and a long tradition of hosting U.S. presidents. In 2010, however, undone by the global financial collapse, it filed for bankruptcy, and Anschutz joined a consortium of investors that bought it.

One of his partners “wanted to change some of the rooms and some of the dining facilities into this kind of glass throne. White everything, white rugs, white upholstery, and I thought, ‘That’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard. Who would do that on purpose?’ ” Last summer Anschutz succeeded in buying out the other parties and becoming the resort’s sole owner.

Employees at the Broadmoor and Sea Island talk of meeting Anschutz while “out poking around, and in getting to better know the people employed there.” Last summer, while visiting Sea Island, he came across a slave cemetery behind a golf course. “If you can show that you are a direct descendant of a slave, you can still be buried in that cemetery.”

He brought up the cemetery when I asked him what appeals to him about Sea Island, then proceeded to talk about Indian tribes inhabiting the area, burial mounds, Spanish forts, pirates, and a particularly fierce battle that took place between the English and Spanish close to the resort. “There are so many layers of history here.” Being proud of your history, and treating such history as an advantage, struck him as so obvious he couldn’t imagine doing otherwise.

A wedding was taking place at the Broadmoor. The Hotel Bar, next to the Lake Terrace Dining Room, was filling up. In the lounge, where three epic paintings of Colorado by Maxfield Parrish hung, the light dimmed outside as a pink sun settled behind Kineo Mountain. Guests and porters crisscrossed the high-ceilinged room, pouring out of elevators, hustling trays of cocktails.

The only thing that didn’t seem to be in motion was a slightly taciturn older man in a purple shirt sitting alone on a couch and studying the activity around him. If anyone knew it was the 39th-richest man in the country and the owner of the hotel, it wasn’t obvious.

For a moment it seemed significant that a wedding was taking place, given the owner’s philosophy. “Owners like Philip Anschutz are very unusual,” Leone says. “These are national landmarks, special architecturally, environmentally, and because of their location in the country. There are only so many of them around.”

You Might Also Like