Meet Pauline Black, the Originator of “Rude Girl” Style and Duro Olowu’s Latest Muse

Pauline Black, the “defiantly chic” frontwoman of the Selecter, a politicized two-tone ska revival band formed in the late ’70 that is still making people dance, is no stranger to fashion. She famously played with androgyny by adapting the tailored, mod-ish Rude Boy style to her own stylish purposes while performing music that was a pointed response to Thatcherism in ’80s Britain. It’s safe to say that pussy-cat bows and big handbags have never been her thing—nor frocks for that matter. “Effortless” is how Duro Olowu, who named Black a muse of his Fall collection, has described her style; she calls it sharp. Certainly, there’s nothing ad hoc about this musician-actress-author’s look.

“Now that British Vogue has a black editor, which I think is a very good thing, there is generally more discussion about black fashion ideas. I can only assume that I popped up on Duro’s radar [through old photos],” muses Black on the phone from the U.K. “The one thing I never did really was wear dresses, and Duro’s quite strong on dresses. The things I like from his shows,” Black notes, “are the longer coats where he mixes fabric and also patterns. He’s quite partial, I think, to a bit of black-and-white check here, there, and everywhere—and similarly, other color checks as well, taking a clean [silhouette] and mixing it with more African styling [and] fabrics.” While we stand by to see if she’ll wear any of them when the Selecter cohead a tour with the English Beat and Ranking Roger this Fall, Black takes us through the inception and evolution of her inimitable Rude Girl look.

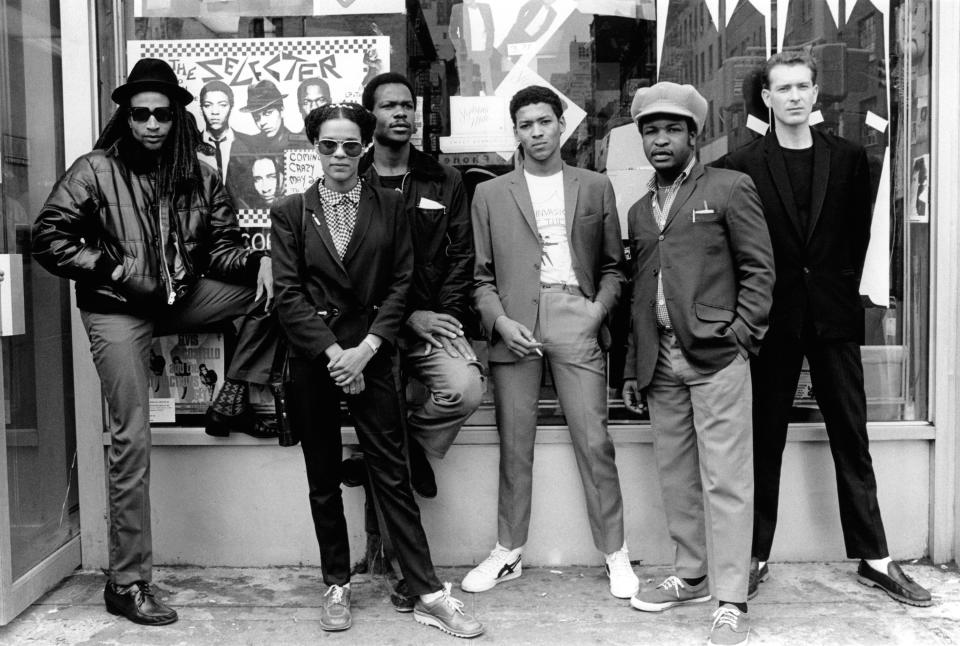

ER1001_SELECTER

The Greed Decade is back in fashion; can you talk about your ’80s look?

I guess my ’80s fashion began when I joined the Selecter, which was part of the two-tone movement: black people and white people playing in the same band, which was quite a strange phenomenon at that particular time. The iconography was black and white: black-and-white check, black-and-white clothing; I guess it was a case of form follows function, in a way. I don’t think we were the first to do it, but we were the first to get noticed in that way. People were just instantly interested in what we were wearing, and what we were wearing harked back to ’60s—and some ’50s styling, in terms of our shirts and things like that—very sleek kind of black pants that were short so there was ankle showing and maybe socks. Loafers were very kind of de rigueur as far as I was concerned.

A lot of those fashions weren’t happening overground, so we had to go underground [to find them]. When we visited America, we would scour thrift stores to get these fantastic clothes because that’s what we remembered from seeing movies in the ’60s. That was how I first started on that quest; over time [I] moved away from just a strict black-and-white look. Some color has been added, [like] red—that’s very in keeping with our more leftish way of looking at the world in terms of our political (but still very inclusive) message. For a while, I liked olive green, that army-ish kind of look which was a good look and still meant business when you got on stage. I would just call it sort of an alternative way of dressing.

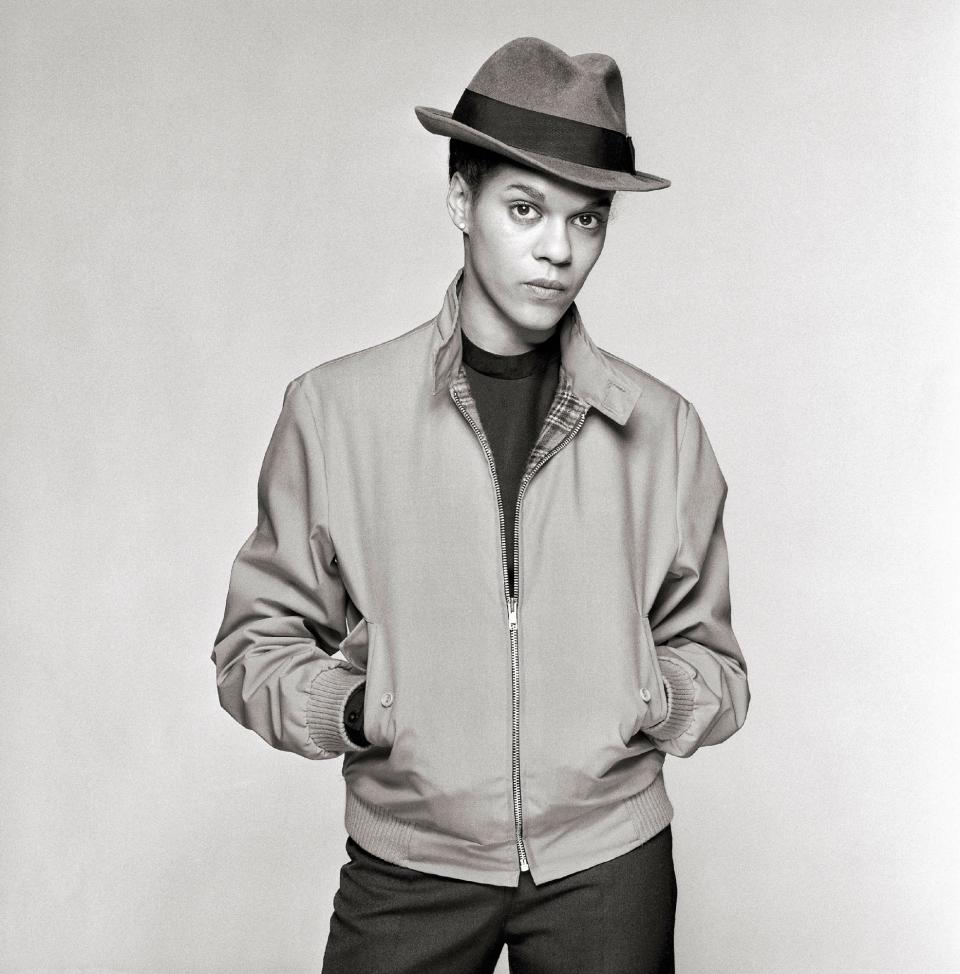

ZXX80001725

Was the tomboy styling deliberate?

That was totally and utterly conscious on my part. It was one of those situations where I was having to decide upon an image and there were no other women doing the kind of music that we were doing. If they were, then they were very much on the side of pink spandex—that whole kind of disco [look] that Chic and Donna Summer had—and I really wasn’t into that. I was much more familiar with a punk styling, but at that time, there were not really any black female punks as such. There were people like Siouxsie Sioux and Chrissie Hynde—but you wouldn’t necessarily peg her as being punk—and Debbie Harry, of course, who could wear anything at all and still look fabulous.

For me, it was very much having to get something that I felt comfortable with. I kind of looked around at what the guys were wearing, [which was] that whole ’60s styling: Little black trouser suits with tapered black trousers, loafers, white socks, and red Harrington [jackets]. All of those things were there and available if you looked for them in alternative shops, so I kind of cherry-picked what I liked. I could always find a blouse that was either checked or black-and-white with some white detailing on it. Those kind of things were around during the ’80s before it went full-on kind of modern romantic. I put this image together which was basically like a mini Rude Girl: Certainly, that was how it was termed at the time.

Can you describe the Rude style?

There is quite a famous photo of the Wailers and Bob Marley—long before he grew locks—he has very short hair and he’s dressed in a black suit with a white shirt and a black tie. In Jamaica, that is what would have been called a Rude Boy, someone who kind of felt himself stylish. I’ve always felt [the look] was taken very much from that 1960s styling that was around then that you could see in all kinds of TV shows and people like Malcolm X, who kind of dressed like that as well.

Did you look up to anyone style-wise?

Not necessarily in terms of style, because there were very, very few women around at that time who were famous or overground who weren’t wearing dresses. I suppose a lot of people would probably look to Patti Smith, but I didn’t really go with that whole image. I like to look smart and always have. I was born in the ’50s; I’m from that generation where when you looked at your mum, she was always wearing white gloves and hats with her Sunday dresses. I love those little details that finish off an outfit and stop it looking too masculine. If I add red leather gloves to what I’m wearing, or a broach to the hat, or just style it slightly different with a scarf, then it gives it that look of femininity, but it’s still sharp.

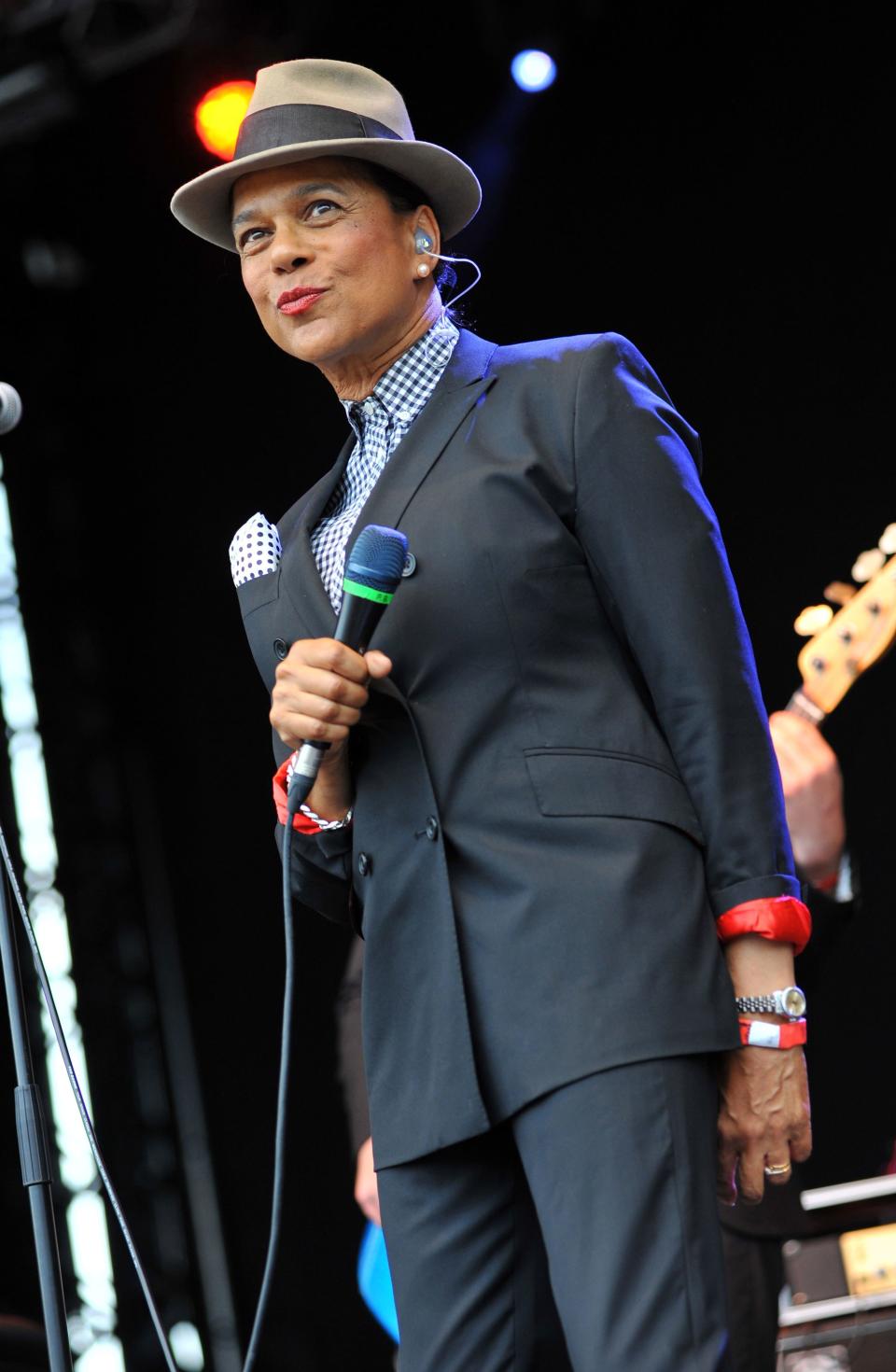

Selecter

One of your signatures is a hat. How did that come to be?

If you want to get ahead, get a hat, as they say! It was just one of those things that was just an immediate identifier, and part of that old Rude styling. If you look at photos from the Windrush arrival of Caribbean immigrants into Britain, most men were wearing hats and quite baggy suits. I think that they took that from the ’40s, Humphrey Bogart . . . any of that kind of people, they always had a trilby. They could come in various forms; some of them were pork pie, which was more associated with jazz styling—Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane—and it just kind of filtered down.

I wasn’t wearing a hat at the beginning, but one of the roadies for the band the Specials, who were an all-male two-tone band, [was wearing] a hat, and he said, “Try this on.” I did and instantly it just made everything look sharp. You just get those moments, don’t you, when you just need one detail to finish off [an outfit], and that was it. It was also one of those things that kind of gave me an androgyny. I see nothing wrong with androgynous images; I mean, I’ve always been really into Mick Jagger, who is the epitome of androgyny while being rather deliciously straight at the same time, probably. I thought, “Hey, two can play at that game.”

Huty17540404

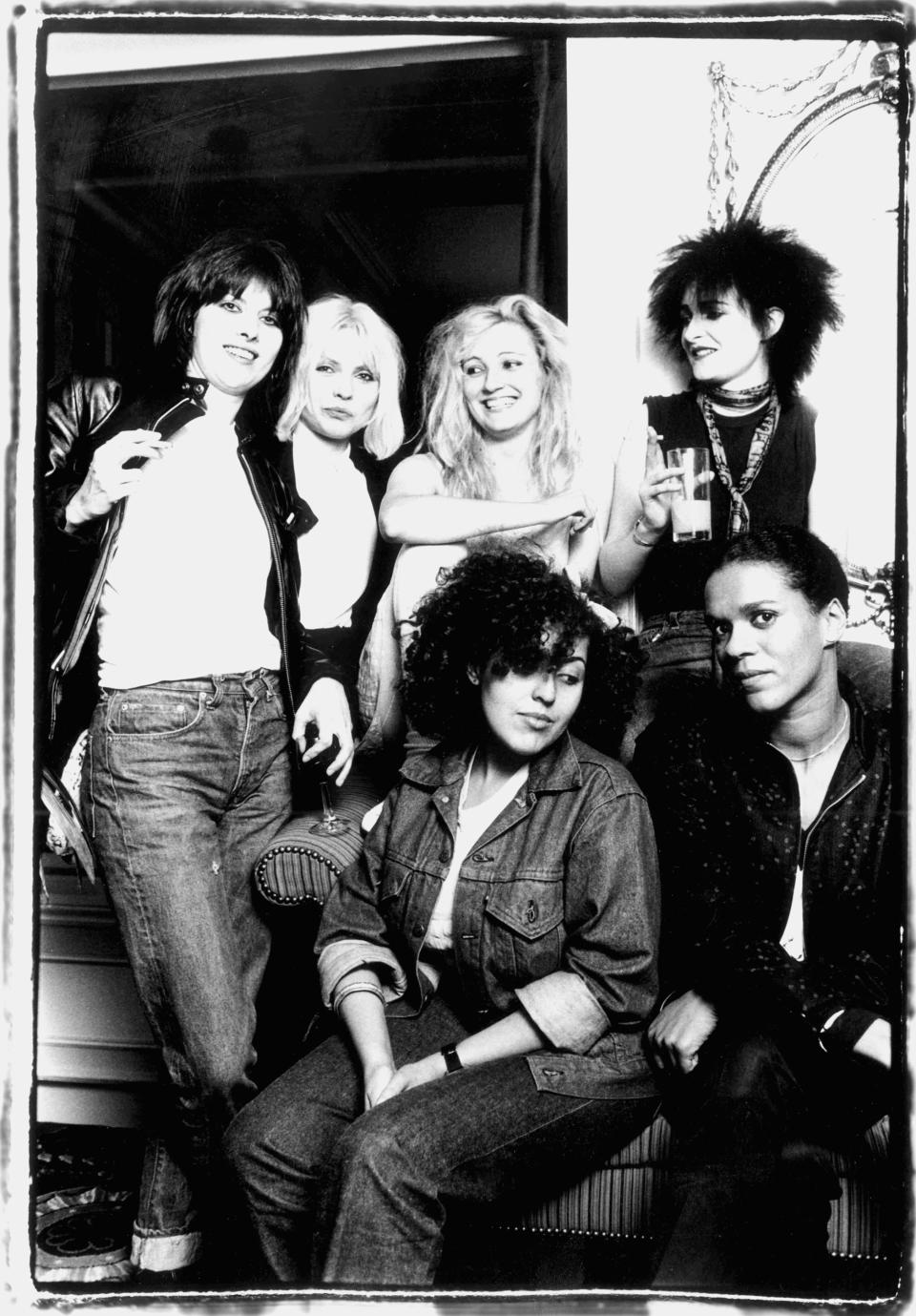

How do Brits approach style differently than Americans?

I think the main difference between England and America—and it’s not strictly true because all things break down at some point—is that people aren’t afraid to experiment. Our styling here was pretty different from bands in America like Blondie, the Ramones, and Patti Smith. They would never have come up with the Mohawk hairstyle, they would never have come up with people like Poly Styrene and X-Ray Spex, who appeared on TV in a German tin helmet and all kinds of accoutrements. It was just a fearlessness. I mean, you had this idea in your head about how you wanted to look and you’d just kind of try things on; some things worked and some things didn’t. That whole Rude Boy styling, for me, just developed into something else that was kind of new; it wasn’t a look for females, and it certainly wasn’t harking back to some other style—ladies with beehives and short shift dresses and things like that, although I admired that kind of thing, too.

86175483

How has your style evolved?

The biggest change is that I can afford more expensive clothes. My black suits are much better tailored; which I think you require as you get older to affect the same kind of look.

Prada for me is a go-to if I’m looking for black tapered trousers that have a little bit of stretch in them so they’re easy to move in on stage but have really kind of good, sleek ’60s lines, and I have discovered, well, I should say I have been discovered by, the guys who design Art Comes First. They’re menswear designers and do the most fantastic leather jackets—good soft leather—and they will put designs on the back for you. I have a great one that says “Selecter” in that kind of punk, Clash kind of writing. [When I wear leather jackets I put] something soft underneath, like blouses, and I’m still keeping that black-and-white check together.

What makes an outfit for me are those sharp and crisp lines. I see going on stage as kind of girding your loins, almost. I always lay my clothes out as though it’s armor. When I go on stage I’m ready to do battle, I’m not there to—what can I say . . . pretty things up.