Meet Mr. Romance, Hugh Jackman

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Here's how we're used to seeing hunky male superstars in their downtime: tuxedoed up on the red carpet, holding hands with pencil-thin beauties. Or driving absurdly expensive cars through Beverly Hills. Or, bleary-eyed, exiting ultra-exclusive nightclubs at 3 A.M.

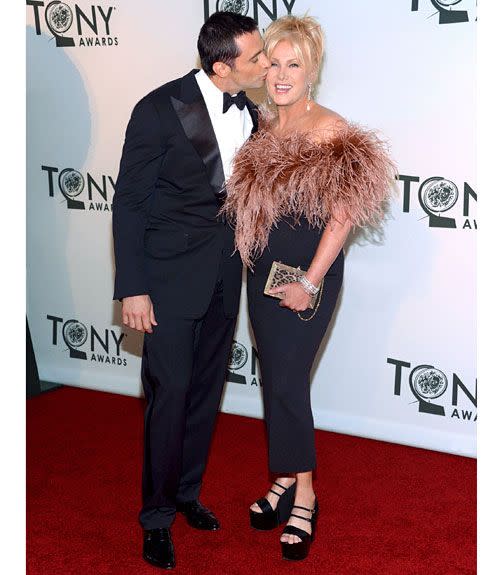

Not Hugh Jackman. The Oscar nominee and Tony winner, 44, who moved us to tears in Les Misérables and who stars this summer in The Wolverine as the hirsute X-Men superhero, is an almost shockingly normal family guy. He's snapped by paparazzi walking around his New York City neighborhood in well-worn jeans and a sweatshirt. He might be clasping the hand of his daughter, Ava, 8, and holding her scooter as they head for a park. In other shots, he's walking with his son Oscar, 13, or strolling arm in arm with his wife, Deborra-Lee Furness, 57, a glamorous platinum (yet refreshingly real-bodied) blond. There's one constant in these photos: Jackman looks completely content.

His path to this happy place wasn't easy. A bumpy childhood in a fractured household—one in which faith was a hugely helpful element—led him to focus on total togetherness with his wife and kids. Jackman is fiercely protective, guarding them from the downsides of celebrity. Yet somehow that protectiveness hasn't cramped their lives or made him any less sunny. As he sits in the green room of a radio station, his friendly, Wolverine-bearded face lights up, and he waves his muscled arms around energetically as he talks about his clan in jaunty Australian cadences.

Oscar and Ava, both adopted, are the apples of his eye. "Ava's really social. She's a mini Deb—she's up for anything," Jackman says. "And if there are three things to do in the afternoon, she'll make it five." Oscar is a young idealist. Jackman has made it a rule that both kids must do volunteer work when they turn 13, so his son, who loves plants ("He can give you the botanical name of every tree in Central Park," Jackman says proudly), is helping tend a nearby park's garden. But he put his foot down on weeding, on moral grounds: Oscar "wanted to know, who's to decide one plant is right and one plant is wrong? They're all part of nature in his book!" says Jackman, obviously charmed.

This kind of closeness doesn't happen by accident. Even during the arduous filming of Les Misérables in England, Jackman says he and Furness followed their unbreakable marriage rule: Jackman will never be apart from his family for more than two weeks. Even if it's only for 36 hours, he will jet home from a film set. The rule was Furness's idea. "When I met her," Jackman explains, "she'd already done about 20 movies," and she understood distance's effect on intimacy. "She said, 'It's not that I think you're going to go off with a costar, or vice versa. But people get used to living apart. You get used to handling a problem yourself.' " Relationships crumble that way, and the actor had already seen one crucial union deeply hurt by distance.

Lonely Boy

The youngest of five children, Jackman was born to parents who had moved from England to Australia before he was born. When he was 8, because of conflicts within the marriage and because her own mother was very sick in England, his mom, Grace, moved back to her home country, leaving her accountant husband, Christopher, in charge of the children almost all year (she'd return for several weeks in the summer; Jackman has fond memories of those visits).

It was undeniably painful for Jackman. "I was embarrassed," he says of the situation. "I felt everyone was looking at me, like it was a weird thing. Some divorce, obviously, was happening, but it wasn't so prevalent then, and it was never [with] the mother leaving."

Then there were other swirling emotions: "I was sad. And upset. And I wanted her to come back." Plus, he was lonely. Being the youngest, he was the first home from school, and sometimes he couldn't bear to walk into the empty house—he just waited outside for an older sibling to arrive.

Because Jackman, like any child, wanted to believe his parents' separation was only temporary, a flicker of hope came when he was 12. His father went to England to try to win back his wife: "They almost reconciled—I remember being so happy." But when his dad returned a mere five days later—alone—Jackman knew it wasn't happening.

"I was really mad," he says. But his anger at the situation didn't turn into venom toward his mother, with whom he is happily in touch today. He understands her. "My mum and I are, in many ways, quite similar," he stresses. "We're both creative, gregarious, and energetic."

As he got older, Grace encouraged him to express his feelings to her. "She would say, 'I know that you'll be angry. I know you'll have this issue. Let's just talk it through,' " he explains.

He gained new perspective as he matured. "The older you get—the more times you have your heart broken and you break someone else's heart," he says, "[the more you realize], Mom and Dad did their best with what they had. I understand why people would say to me, 'I don't know how you'd ever talk to her again,' but what happened was about their marriage, not their parenting."

In fact, he says, pausing to pull into focus a comforting truth, "I always felt love from both my parents."

Jackman's father gave his youngest son a grounding in faith and values that nurtured him through hard times. Although both Jackman's parents were very religious early on, Christopher Jackman was the parent whose faith deepened over the years.

"My father is very Jean Valjean," Jackman says, referring to his own character in Les Misérables. "He's what I would call a great example of a religious person. He is a deeply thoughtful man whose religion is in his deeds way more than anything else. It's not talked about that much.

"I remember at one point being in fellowship," he continues, "and everyone used to wear the fish symbol; it said you were a Christian. So I asked my father, 'Dad, why don't you wear that at work?' And he said, 'Your religion should be in your actions.' He set a great, great example."

Jackman's father also taught him responsibility. With five kids and a heavy work schedule that often had him traveling, he made sure the children shared the load. "From when I was very young, I had chores every day. I had to cook dinner, or no one ate," Jackman says.

Beyond that, Jackman's father—who had grown up during the Depression—taught his brood about thrift. "When I was 5, my father used to sit me down and explain that from my dollar a week, I should set aside 10% for church, 20% for entertainment, and 10% for savings."

Armed with these valuable life lessons, Jackman was ready to find his place in the world when, fired up by his love of performing, he left home, pursuing an arts degree in college and then drama school.

Meeting His Match

In October 1994, Jackman, 26, a freshly minted drama-school grad, went to audition for a new Australian TV show, Correlli. He tried not to show how nervous he was. The drama was set to star Deborra-Lee Furness, a blond beauty with a husky voice, as prison psychologist Louisa Correlli. Furness, then 39, was a top actress in Australia, and Jackman was up against some of the country's megastars for the role of Kevin Jones, the mentally challenged prisoner who forms a bond with Correlli that nearly leads to her professional undoing. In their first scene together (it can be found on YouTube), Correlli is compassionately interviewing Jones, who radiates charisma—helped along by an earlier lingering shot of him shirtless—and the pair's chemistry is on full display. "From day one, we were best mates," Jackman says, putting a wholesome gloss on their electric attraction. "We just clicked. We were giggling and laughing—we just connected."

They fell in love—fast. Jackman was and is clearly head over heels. He explains, "Deb is the last one to bed and the first one up in the morning. You know those dolls that, when you lie them down, their eyes close? And as soon as they're vertical, their eyes open? That's Deb. It's almost annoying. She has two speeds: Stop and Go. She is always, 'Let's do this, let's do that.' And she is very funny, very quick."

Three and a half months after they met, Jackman had a platinum and rose-gold diamond ring specially made for Furness. Soon thereafter—with his self-confessed romantic streak blazing—he planned a surprise proposal. He enlisted a friend's help to set an elegant table with croissants and flowers by a lake at a botanical garden and then lured Furness there on the pretext of taking an A.M. walk. When they came upon the table, "Deb just stopped and said, 'Oh, my God, it's gorgeous,' " he says. As if in a chick flick, a group of school girls arrived and watched. "And I whispered in her ear, 'Surprise,' " Jackman says; he pulled the ring out and proposed. Furness started to cry, but then the schoolgirls asked her, "What did you say?" With theatrical flair, "Deb stood on top of the table and called out, 'I said yes!' " he recounts. Eleven months later, in April 1996, they were married.

That sneak-attack element has become Jackman's calling card with Furness. "My number one rule for romance is surprise," he says, since predictable gestures of romance defeat the purpose. "If I bring Deb flowers every Tuesday, yeah, it's nice, but is it romantic?" Especially when a couple has children, "so much of life is about your routine," he says, and a surprise shakes things up and restores the thrill. Recently, for example, when Jackman got off early from work in Montreal, "I pretended I was still on the set. I called Deb and said, 'I'll be back late tonight.' " Then he appeared hours earlier than she expected. "And she got such a shock. I'd made reservations at our favorite lunch place," he says. "It was three hours before the kids finished school, and it was awesome because it was unplanned."

And for a surprise Mother's Day gift, Jackman stealthily snagged a beautiful heart-shaped artwork that Furness's favorite fashion designer, Oscar de la Renta, had crafted for charity. She received another treat that day, too: Her husband whipped up some special ricotta pancakes—"I got the recipe from our favorite breakfast place in Sydney, Bills. She just loves it." But as happy as the Jackmans are, and as normal as they may strive to be, celebrity has its drawbacks.

Reeling From the Rumors

This past spring, their lives were upset when a troubled woman stalked the family, ultimately bolting into the gym where the Wolverine star was working out and saying, "We're getting married, right?" Katherine Thurston, the stalker (who has pleaded not guilty), was taken into temporary custody while awaiting her next court date, and the family could breathe a sigh of relief.

Less perilous, but more lingering, is the impact of gossip: Over the years, some websites have printed tiresome speculation that Jackman is gay—those almost knee-jerk rumors lobbed at many sexy actors. Jackman just tunes it out: "I don't really pay attention. If someone's going to spend their time saying, 'You're really not 6' 2"; you're 5' 10",' " he says, using height as an analogy for sexual orientation, "I'll tell them once, 'I am 6' 2".' Then, whatever you want to believe, it's up to you. Am I going to waste energy going, 'I'm so mad that this person says I'm 5' 10"?' " He shakes his head. "We really only get mad when there's an element of truth, right?"

By not reading the gossip, he also avoids the nasty comments about the fact that his wife is older than he is and has womanly curves (versus being an ultra-skinny size 0). And this is a good thing, because any criticism of Furness really gets him going. "If anyone meets my wife, they're like, 'You're all right, Hugh, but your wife is awesome.' Everyone who meets her loves her. So it's just wrong. It almost makes me sad for the people [saying those things]. They're obviously in a bad place."

Still, the gossip takes its toll on Furness, who is less successful at tuning it out. "I don't want her perturbed; I worry for her," Jackman says. What angers her most are the rumors that their marriage is a sham. "She's a justice freak," he says. "When she hears the gossip, she finds it hard to shut up about it. It's frustrating that she doesn't have a voice in the situation."

Jackman's remedy: He lets Furness vent to him and listens sympathetically: "I know she's always right when she says, 'Just. Listen!' "And for his part, he hears her out and empathizes without jumping in and trying to resolve the issue.

"We talk about everything all the time," says Jackman, noting that they often take nighttime walks with the dog in tow and chat about their days. "The bedrock of any relationship is to communicate, and Deb and I have always done that, discussing whatever's going on, good or bad." And their marriage—like all unions—has had its highs and lows.

Creating Their Clan

When Jackman and Furness married in 1996, they wanted to start a family right away. Their plan was to have biological children and then adopt. "That was something both of us had always dreamed about," Jackman says. "One of the families I used to stay with when my parents separated had five kids; two were adopted, so it didn't seem abnormal to me."

Since Furness was 40, they tried to get pregnant for about a year, then started in vitro fertilization. Twice she became pregnant; twice she miscarried. "It's a tough process," Jackman says. "While you're going through IVF and get pregnant, every day [the feeling is], We're still holding! We're still holding…! You know how precarious it is and how much she's been through to get there. And [miscarriage] is a massive letdown. It's really difficult—and much harder for the woman." After their second miscarriage, "I just remember saying to Deb, 'We've always wanted to adopt. Let's start going about that,' " he recalls. Furness agreed, but decided she wanted to continue the IVF efforts.

However, Jackman shares, "there was a rule in Australia at the time that if you were going through IVF, you weren't eligible to adopt." They set their sights on going to the United States, both because that rule didn't apply there and because the pool of adoptable babies was much larger.

This was about 14 years ago. Jackman was all but an unknown in the U.S. "We came to L.A. for a week to meet with an adoption lawyer," he recalls. The couple thought it would just be a brief visit, but that trip wound up jump-starting their lives as parents—and Jackman's stardom.

Since they were already in Hollywood, Jackman made an out-of-the-blue call to his U.S. agent. The timing was serendipitous. Just that morning, the agent had heard that an actor had dropped out of the lead role in a movie based on the comic book series X-Men. Would Jackman like to go up for it? he asked. A meeting turned into more meetings and a screen test, which turned into a trip to Toronto, where the movie was filming ("We had to buy clothes; it was snowing," Jackman adds)—and all of a sudden, a starring role was his. The salary, in turn, helped further his and Furness's family plan, because "adopting does cost a bit of money and I really didn't have any at the time," Jackman says.

As they worked with their adoption lawyer, Jackman says they wanted a baby most in need of a home; he has called it a "no-brainer" to ask for an interracial baby: "People wait 18 months to adopt a little blond girl, while biracial children are turned away." Still, they were rejected by a few birth mothers' parents who didn't want to give a child to "those Hollywood types who never stay together."

Finally, in the spring of 2000, they received news of a baby about to be born; he or she would be "a bit of everything," as Jackman has put it: "African-American, Caucasian, Hawaiian, Cherokee." When Oscar arrived, the couple were ecstatic. "Deb and I both thought, 'This is our destiny.' " Indeed, the trip to L.A. had catalyzed Jackman's career in the U.S. and had given them the baby they had so yearned for. "It was as if Oscar was going, All right. I'd better look after you guys," reflects Jackman. Five years later, they adopted Ava—half Mexican, half German—at 4 days old, and their family was complete.

The family's bond is superhero strong, no matter where Jackman is filming. "Skype has changed our lives! It's one of the greatest inventions of all time," he raves. Of course, his kids don't always think so, he adds. He Skypes when on location; he eats in front of it, and they do, too. "So I'll have dinner with them and then say, 'Hey, take your plate to the sink!' And they're like, 'Ugh, Dad's such a pain.' "

Jackman is the family disciplinarian—which figures, given his upbringing—and Furness, who was an only child until her mother remarried and step-siblings entered the picture, is more spontaneous. They complement each other well. "Oscar and Ava fight, like all kids fight," Jackman says. "But it really disturbs my wife: 'Why aren't they getting on? Oh, my God! It's going to be years of therapy—they're saying terrible things to each other!' But I look at it like, 'This is nothing! This is amateur hour!' My brother and I were clawing each other's eyes out at one point," he explains, laughing at the memory.

Though he may have two Tony awards and an Oscar nod, it's clear that Jackman's favorite times aren't in front of the camera, but with his wife and kids. As he puts it, "The most pressing thing for Deb and me now? Helping the kids reach their potential. And having fun."

You Might Also Like