Meet Glamour ’s 2020 College Women of the Year

The women are ice-skating scientists, models-slash-engineers, published authors who happen to be D1 athletes, Rhodes Scholars, and small business owners. They are first-generation Americans, first-generation college students, future Ph.D.s, airline pilots, public servants, educators, and mentors. They have stared greed and power in the face and won. They have demanded more—more accountability from institutions, more truth-telling in the media, more humanity in systems that seek to treat humans like objects. They have taken up space and used it well in a world that was built by and for men.

Glamour’s 2020 College Women of the Year are coming of age in a world bubbling over with sickness, racism, inequity, and environmental devastation. And yet each one has made extraordinary efforts to clean up their share—and then some.

Read on and memorize their names. These are women to watch.

Cat-Sposato

Tiamera EllenCat Sposato

Columbia University

Cat Sposato’s life was like a movie—one of those inspirational movies that people go to to see how the American dream is available to anyone who is willing to work. The 21-year-old was raised by a single mother in a low-income household in Passaic, New Jersey. At the end of high school, she was accepted to 16 colleges, including Harvard, Yale, Penn, Columbia, and Brown. She chose Columbia, the school that educated three U.S. presidents, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Warren Buffett. Sposato marching triumphantly through Columbia’s giant wrought-iron gates should have been the last scene in the movie. “People assume that once you’re there, you’re in, you’ve made it,” she says. “But it’s just another battle.”

Before school had even started, Sposato participated in an orientation program where she was warned not to, in essence, make people feel bad about their privilege. She says some professors told her to watch her tone. “I had never been spoken to that way,” she says. She noticed how many stumbling blocks stood between low-income students and success. “STEM courses require you to have taken an A.P. course to survive, but people I know struggle, because if you went to an underfunded public high school, you weren’t taking A.P. classes at the same caliber,” she says. Getting internships and jobs, she observed, wasn’t just a matter of working hard and having a good degree—the people around her were using connections she didn’t have.

Some students spend their time thinking about whether they should go skiing for winter break. Others, Sposato noticed, are worried about what they’re going to do in the winter, when the temperature drops and they don’t own a warm coat. “It’s so frustrating to see people have the college experience as if it’s on TV in front of you, and you’re like, ‘I’m living a completely different life, but we’re sitting right next to each other.’ It’s overwhelming."

Since the moment she got to campus, Sposato has been working to change that imbalance. She joined Columbia's First-Generation and Low-Income Partnership group, first running social media, then rising to the level of copresident. “We really want to have conversations in elite spaces that are authentic without someone policing our tone,” she says. She listened to community concerns. She worked with the group to purchase warm coats for low-income students who needed them for the freezing New York winters. But students shouldn’t be buying students coats—it’s a systemic problem.

Often, the role of the group is “providing a service and trying to get that program institutionalized to demonstrate to the administration that there’s a problem,” she says. Her group’s normal activism hit crisis levels when the pandemic began, and Columbia, like many other schools, started, in effect, evicting students. Sposato and her colleagues worked around the clock, encouraging administrators to remember first-generation and low-income students too. “Whatever you think the traditional student can do,” Sposato remembers telling administrators, “scrap that.”

Coat drives and making connections are a stopgap, Sposato realizes. Changing the narrative by speaking it into existence is more powerful. She started her own radio show to elevate Latina, first-generation voices, and published opinion pieces in the Columbia newspaper. She cofounded a podcast, Primerosas, on which she and her cohosts talk about Latinx culture, anti-Blackness, respectability politics, and sometimes makeup. It’s work she hopes to keep doing after she graduates.

“A lot of my academic work centers prison abolition and prison reform,” she says. “And being in those spaces the one thing I learn all the time is they’re filled with jargon, they’re filled with rich white people, people who aren’t at risk for incarceration. I want to take those discussions to people in my community.” She wants to use media as a way to bring those conversations to her community, and to communities that are actually affected by the issues spoken about with such authority behind the walls of Ivy League schools. “I think the thing I want to be known for doesn’t exist,” she says. “I’m going to have to make it.” —Jenny Singer

Diana-Reyna

Diana Reyna

Texas A&M University

According to historians, Marie Antoinette never in fact said “Let them eat cake” in response to the news that French peasants were starving. But it’s one of our favorite historical fibs for a reason—when faced with the news that life for regular people is untenable, people in power often reveal their ignorance. And that leaves normal people to find solutions to things that seem impossible, like figuring out how to, for example, pay rent during a pandemic that has made millions of Americans suddenly jobless, or go into hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt in order to get an education.

Diana Reyna—a 20-year-old first-generation college student from Houston, has given the phrase a new twist: Let me feed them cake. Cheesecake, to be exact. Facing the rising cost of a college degree, Reyna rolled up her sleeves and got baking.

She hadn't planned on running a cheesecake business, much less during a pandemic. And yet, if you call the phone number for Pastelitos, her Houston-area bakery, you’ll get Reyna on the phone. She’ll politely take down your order for a cheesecake made with ingredients she bought, prepared in a facility she runs, often baked with her own hands.

Growing up with an eye on being a first-generation college student, “financial need was always on my mind,” Reyna says. It was never an option for her to just relax and have fun, she was constantly thinking about how to pay for all of it. When she got into Texas A&M, she had landed herself so many scholarships that most of her first-year tuition was covered. But many of them were one-off scholarships. “It was the summer of 2019 when I found out I wasn't going to get about $10,000 that I had gotten the last year, and I had to make it up if I wanted to continue going to school,” she says. “I remember when I found out, I literally lay on my couch in complete silence for eight hours trying to make up ways in my head I could afford school.”

“That entrepreneur part of me was, like, triggered once I found out how much college tuition was,” she says. “I'd never seen a number that big on any bill, ever!” She wanted to make and sell something that had value—some kind of work from her hands that she could turn into college tuition. “I am by no means a kitchen-slash-cooking person, so I immediately took to the lovely internet to figure out things besides your regular-schmegular box cake.” She landed on cheesecake—the most Pinterest-perfect, visibly creamy, crumbly-crusted cheesecake. She started by making and selling them individually, reaching potential customers through Twitter. Then she started catering parties. Then she moved into a brick-and-mortar bakery, a communal space where she works with a student-led Latinx staff. Together, in their cheerful blond-wood bakery, dripping in pastel flags and flushed with light, they’ve made more than 2,000 cheesecakes.

Along the way, women in her life—her grandmother and mother, in particular—support her in everything. A woman professor and another woman baker in the community offered their assistance. The women in Reyna’s family “follow me around hyping me up with everything I do,” she says. “I've never seen one woman in my family who has ever backed down from a challenge.”

Reyna not only met her challenge; she crushed it. She’s a business owner, paying her way through school, feeding her community in love and cake. “The only dessert I found that truly satisfied my pregnancy cravings,” writes one Facebook reviewer. “I will never purchase another cheesecake from anywhere else after trying this one!” writes another. Reyna’s favorite is “cocoa caramel with pecans, without a doubt! the prettiest, best tasting, aesthetically pleasing cheesecake in the menu. There’s just no way it can come out ugly.”

Cocoa caramel, Oreo, carjeta, white chocolate—whatever flavor of not at all “regular-schmegular” cheesecake you’re craving, here’s what you need to know: Pastelitos cheesecake order forms for cakes in Houston and College Station go up on Twitter twice a week, and sell out most of the time. They accept payments on Venmo, Zelle, and CashApp, as well as plain old cash. They might be playing soft indie music when you come to pick up your cake.

Oh, and one more important thing:

“Women and nonbinary business owners are so often degraded and not taken seriously—people don't believe they can run a business the way a man does,” Reyna says. “I can't even remember all of the times I've been told that what I'm doing isn't sustainable or that it was just a fundraiser and let it go. The difference between a fundraiser and my business is that when I saw the opportunity to create something larger, I did.” —J.S.

Wanjiku Gatheru

Omar TawehWanjiku Gatheru

University of Connecticut

Wanjiku Gatheru (known as Wawa to her friends) was about to leave for the airport when she found out—and not for the last time—that her senior year at the University of Connecticut would not conclude as planned.

It was August, just before the start of the fall semester. Tickets in hand, she had intended to spend the next few months in Hong Kong. But because of political protests, Gatheru was told her program would be canceled. In less than a week, she had to find a place to live and squeeze into a slate of stateside classes.

Looking back, she's grateful for what would turn out to be the first of several disruptions. With the pandemic putting a swift end to in-person classes in mid-March, that fall semester turned out to be the last full one she’d spend on campus. And despite the late start, she made the most of it.

In November, Gatheru, 21, was named a Rhodes Scholar, which comes with a full scholarship to Oxford. She is the first ever UConn student to be selected for the honor. She joins the ranks of previous Rhodes winners, including former President Bill Clinton, former U.N. ambassador Susan Rice, political commentator Rachel Maddow, and two 2020 presidential candidates—Senator Cory Booker and former mayor Pete Buttigieg. (She was also named a 2019 Truman Scholar and a 2019 Udall Scholar—the triple crown of student awards.)

In the announcement blasted out over UConn’s social feeds, Gatheru was heralded for her leadership, her passion, and her convictions. She serves on a head-spinning number of student boards. She spearheaded a “Ban the Bottle” initiative, which succeeded in persuading several on-campus retailers to stop selling bottled water. She led a survey of food insecurity on campus so impressive that it’s been cited in both federal and state legislation.

But when Gatheru describes herself to Glamour, she doesn’t jump right into all that. Instead, the first word she uses is introvert. Also near the top is nerd. Gatheru grew up in Connecticut, the daughter of two Kenyan immigrants. She's the first to emphasize that her achievements are as much a credit to them as to her. And her work—on environmental justice, nutrition, food policy—is grounded in their example.

“I come from a long line of farmers—for hundreds of years, really, in Kenya,” she says. “When my parents came here, my mom kept a garden. Growing up, that’s how I connected with the land and my grandmother. When I started at UConn, I was like, ‘Okay, how do I continue to work on what I love, but within an academic space?’”

Gatheru got involved with a research lab that was assessing local food insecurity and realized that it wasn’t just an issue in the nearby community. “A lot of the metrics that are being used to assess food insecurity applied to the people closest to me—at UConn,” she says. “But we weren’t talking about that.”

According to Gatheru, the first researcher she raised it with shut it down, but a mentor urged her to look into it. “I don’t think I would have had the confidence to have even applied for a grant to research something that had never been researched—not only at UConn, but in any public institution in the state—had I not gotten that kind of support,” she says.

At Oxford, Gatheru is planning to pursue dual master’s degrees in nature, society, and environmental governance and evidence-based social intervention and policy evaluation, with a particular focus on the barriers that prevent people of color from participating in conservation efforts.

Some of the blame can be attributed to the roots of the environmental movement, which—as she contextualizes it—was born of a classist, racist reaction to the Industrial Revolution. “In fact, Madison Grant, one of the founding fathers of the environmental movement, wrote a book that Hitler noted as one of his great inspirations,” Gatheru points out. “So a lot of the foundations of the environmental movement were grounded in white supremacist ideologies.”

Gatheru looks up to people like Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, a marine biologist and the founder and CEO of Ocean Collectiv, a consulting firm for conservation solutions grounded in social justice. In general, she admires those in the field who, like Johnson, refuse to do science in a vacuum. “People will say, ‘Keep race out of science or keep feminism out of science, because it’s divisive,’” Gatheru says. “But we need an intersectional approach to environmentalism and to problem-solving, and seeing people like her do that has been phenomenal.”

Above all, Gatheru is not willing to cede her chosen field to its ugliest practitioners—historical or present. Climate devastation is real and affecting people of color all over the world, including her own relatives. While she pushes those who do this work to recognize their own biases, she isn’t waiting for permission to forge her own path. Not now, with the world depending on it. —Mattie Kahn

Marissa Sumathipala

Marissa Sumathipala

Harvard University

Marissa Sumathipala’s life is not easily distilled into a sound bite: The daughter of an immigrant mother from Sri Lanka, she grew up surrounded by cornfields, rose to the level of a preprofessional figure skater, and then, when a concussion derailed her dreams, she started a computational network platform that uses artificial intelligence to map molecular interactions and provide better, faster, cheaper drugs for chronic diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and heart disease. Yes, really. Chronic diseases are responsible for 70% of deaths in the U.S.—because of 20-year-old Marissa Sumathipala, some day, you may be diagnosed with a chronic disease and given drugs that make you more comfortable, that don’t force you to remortgage your home, that allow you to live.

Sure, she’s an elite athlete turned possible cancer curer, but Sumathipala experiences the same set of nerves and insecurities that the rest of us do. Take her experience entering a competitive space—Harvard’s Venture Innovation Incubation Program for start-ups. “I walked in and I was the only woman in the room and all of the other people in the room were much older than I was,” she says. “And I remember thinking, Do I fit in here? Am I doing the right thing? Am I not the right person for this? Should I leave it to someone else who has more business experience? Maybe I’m not cut out for this.”

In that moment, her hard work, her ambition, her slate of awards—the Regeneron Science Talent Search Junior Nobel, the Davidson Fellow, and the Intel ISEF Grand Award, among others—seemed to disappear.

“But I thought about [my] grandfather, and all the other people in my life who’ve been impacted by disease, and I said, ‘I’m going to do it anyway.’”

Sumithapala’s grandfather died of heart disease before she was born. “I got to know him through grainy photos and old stories,” she says. She was a high schooler, but she’d already conquered waking up at five in the morning to ice-skate. Then she decided to go after the disease. “It actually costs $2.6 billion and 12 years to bring a single drug to market. When I found that out, I thought, We’re doing something wrong here.” Through her heart disease research, she discovered something even bigger—a novel approach to find drug targets for chronic diseases. She developed the platform in her childhood bedroom, the same place where she had experimented with growing fruit flies as a little girl who was fascinated by science but preoccupied by skating. She called her project Theraplexus.

“In developing Theraplexus, my idea was really to rethink how we approach disease—the standard approach is to go after the tip of the iceberg, just one or two genes,” she says. “But that approach has failed us when it comes to some of the most devastating, complex and chronic diseases like Alzheimer's and cancer. The idea that I came up with was to not just go after the [basics]—diseases are not caused by a single gene; they're caused by perturbations to these really complex molecular networks that underlie the disease and cause all the symptoms that we see. And so I realized what if we could map these molecular interactions and pinpoint drug targets that would target all of the genes causing the disease at a single time, we could create drugs that were more effective with fewer side effects and get them to patients sooner and cheaper and combat some of these most devastating barriers in drug discovery.”

Lost? “I like to think of it as kind of a Google Maps for molecular networks,” she says. “It searches through these molecular networks and identifies drug targets that can be more effective for treating a disease.” Think of the 40 trillion cells inside your body as talking to each other, a “social network,” as Sumathipala puts it. To make the idea into a reality—“massive manually curated genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic data sets [integrated] into a multiplexed complex network model,” she says—she needed to learn to code. “I basically locked myself in my room with my laptop and a notepad, and over the course of a couple days, I taught myself how to code,” she says. “And when I came out of it, I began developing the platform that is Theraplexus. So far I have found over 200 promising drug targets for diseases like schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, breast cancer, and diabetes.”

The question is—how? How does a 20-year-old accomplish this much? How can she do all this work, that she will most likely not see make an impact for many, many years? “When I was younger, my dream was skating—this personal ambition to achieve physical and artistic mastery in my craft,” Sumathipala says. “But as I got older and after the concussion, my identity felt kind of fractured—I didn’t know what to do, I had built my entire identity around ice skating. I started to rebuild it around this idea of using my talents and my abilities and my love for science to bring good to the world, to combat disease, and to help people live healthier lives.”

It’s that dogged interest in improving people’s lives—in giving as many humans as possible the chance to know their own grandfathers—that drives her. Or, as she puts it: “It’s so powerful that it's kept me going through all the challenges, the setbacks, the barriers of developing something this big, of tackling things like being a woman of color in a field that’s dominated by people who don’t really look like me.” —J.S.

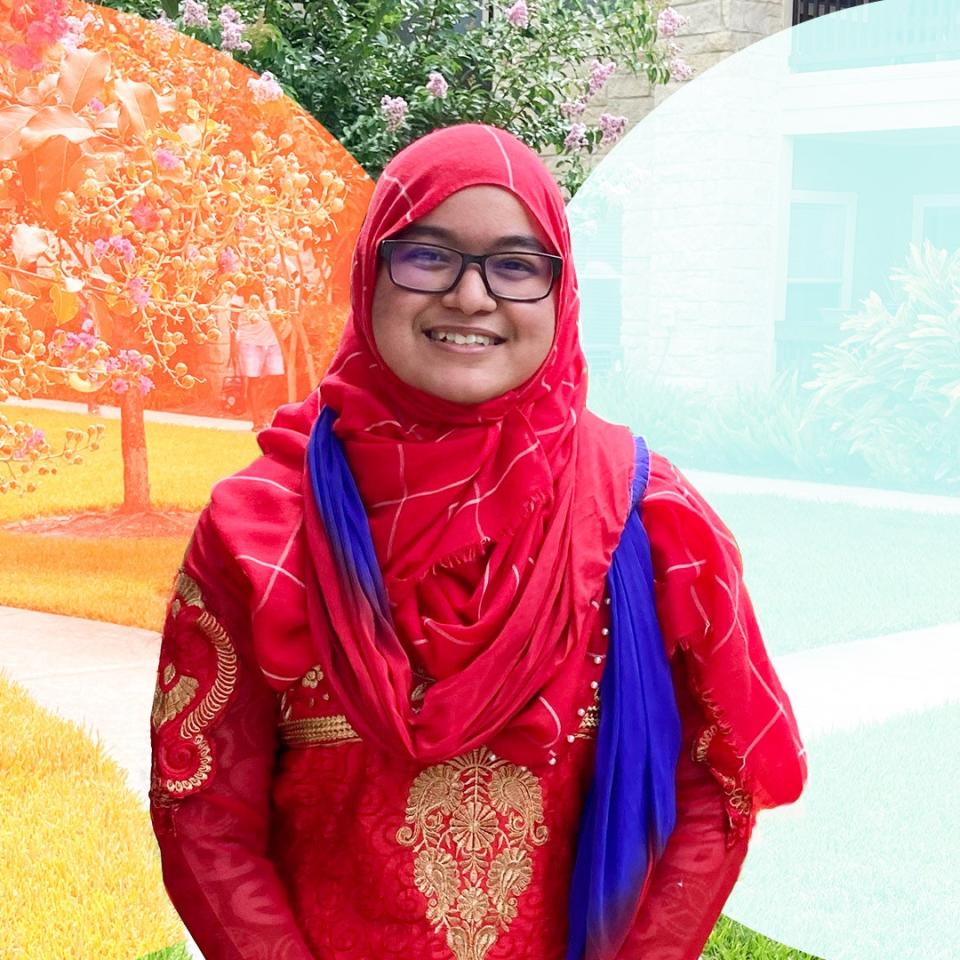

Meherina Khan

Naheda A. KhanMeherina Khan

Harvard University

For a nonprofit, the Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA) is doing quite well for itself. It runs more than 80 programs, including a network of neighborhood-based summer camps that serve more than 800 kids in Boston and Cambridge and two homeless shelters. It has been around since 1904. With such bona fides, it seems like the kind of institution that could be filled with ambitious professionals and a team of well-dressed retirees.

Instead, its staff consists of students at Harvard. A few adult supervisors aside, PBHA is one of the most successful student-led organizations nationwide. (Those shelters? The only student-run organizations of their kind in the United States.) PBHA is such a team effort, in fact, that the organization's president, Meherina Khan, dismisses the notion that her work is that much more important than the rest of its volunteers’. “I’m part of a greater collective,” she says.

But despite her protestations, she does stand out. Khan, 21, started volunteering with PBHA as a freshman. That summer, one of the organization’s camps in Boston’s South End needed a director, and she volunteered. The experience was transformative, not just moving her to continue to work with PBHA, but also shifting how she looked at what nonprofits in general are supposed to do.

“That summer taught me to love and to listen,” Khan says. “It also forced me to think about, What does it mean to be in management of a nonprofit? But at the same time, what grounds you in the work? What are the values that call to you? What moments and what relationships keep you going?”

These are questions Khan doesn’t have simple answers to. But here’s what she knows: “I want to be a part of social change. I want to make sure that whatever it is that I am doing or that we at PBHA are doing is part of a greater mission, is fighting for justice and thinking about what that looks like. Nonprofits exist because we live in a world of gaps in resources and services. In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have to exist, because those things would be there.”

Khan grew up in Katy, Texas, just outside Houston, which is where she's been since coronavirus forced students to leave campus. Organizing from her bedroom, she's grateful at least that the pandemic has allowed for a reunion for her and her younger siblings. In her childhood home, she’s found that the same principles she holds dear at PBHA operate here too. Reflection, dialogue, deep, abiding love—these form the bedrock of social progress.

“I think a lot about radical love, and how that fuels our work,” Khan explains. “In activism spaces and in this era, we’re often fueled by everything that’s wrong, right? There’s so much anger, because there is so much to be angry about. But at the same time, anger can be exhausting.” As clichéd as it sounds, she chooses love instead. Over the past few weeks, as thousands have rallied to call for justice and an end to racism even older than America, Khan has found herself thinking about how “the oppressive structures in our social lives work” and how love and attention—well-channeled—might be able to dismantle them.

“It’s not that people who are discriminated against are not talking,” Khan points out. “It’s not that they’re not speaking up for themselves. It’s that no one is listening. I want to be someone who listens with my full, complete self. But at the same time, I’m cognizant of the fact that—even unknowingly or unintentionally—I’ve probably been a part of these systems that have caused harm.”

“At Harvard, I've become more aware of the privilege that I have,” she continues. “Yes, I'm the child of immigrants. Yes, I come from a low-income background. Yes, I'm a part of a minority population. But the privilege that I’ve had to be able to come to a place like Harvard—that immediately changes the way that people perceive me. Because of Harvard, people now feel a little bit more inclined to hear me out, to make room for my voice. Now I have to think, Well, what can I do with this voice?” —M.K.

Autumn Greco

Kelli SantosAutumn Greco

Stanford University

In New York, Autumn Greco’s high school science classes played out like a giant metaphor for the underfunded American public school system—no matter how carefully students did experiments, carefully measuring liquid in beakers and turning Bunsen burners to just the right height, nothing happened. The chemicals the school owned were usually expired. “I liked asking questions,” the 21-year-old says. “But I didn’t know any scientists. I had never stepped foot in a lab.”

And then one day she asked Google. “I literally just googled ‘summer research programs for high schoolers’ and applied to the first link,” she says. “That experience really changed my life path.” She spent the summer studying acute myeloid leukemia, with women scientists. Entering the world of scientific research, she says, felt like learning a new language. “I really didn’t know how to ask questions of a scientific nature before,” she says. “I started thinking, Really—what is left to know?” The answer was: a lot. And she wanted to know it. But she still didn’t call herself a future scientist or engineer. “I like asking questions,” she told herself. That was all.

She also modeled. Signed to Wilhelmina Models before her 10th birthday, she walked runways, shot print ads, and starred in commercials in between her science work. She attended New York Fashion Week as a high school freshman. She's worked out with Hannah Bronfman.

When she got into Stanford, Greco became the first person in her family to go to college. (She learned about the university, also, from Google, typing in “colleges in California.”) But if she had felt unprepared to pursue a career in STEM, getting to Stanford only underscored the feeling that she should be careful not to dream too big. “I certainly felt belittled when everyone around me was like, ‘Oh, this is so easy. I’ve done this before. I did this in high school,’” Greco says. She found herself working harder, not to get ahead, but just to keep up with her classmates.

“I wasn’t too aware of how much intergenerational knowledge is present at elite campuses like Stanford,” she says. “The people around you who just seem to know what they need to do to get to the next step.” Everything she had done to go from expired chemicals in a high school classroom to Stanford was just the first step, she realized, getting her here. Now she had to prove herself all over again.

But she persevered. She pursued a bioengineering major, making it through the most difficult classes in science, math, and computer programming. She started getting research jobs, teaching assistant jobs, and programming work. She finished off her time in undergrad working in an applied regenerative medicine lab, attempting to answer a question that is both urgent and expansive: How can we harness different cell populations to support healing? Greco has a knack for taking scientific concepts that would be opaque to the average person and reframing them in accessible language. “No one back home knows what this is, so I’m used to making sure I’m not excluding people from the conversation,” she says. “I don’t want anybody to feel like it’s out of their reach.”

Greco graduated in June, amid a pandemic that colleagues in her field are, at this very moment, struggling to understand. She’s headed to a predoctoral fellowship at Columbia University next, and then maybe a Ph.D. in bioengineering, with lots of time set aside to help mentor people who, like her, are coming from a place of little opportunity and lots of curiosity. She’ll also keep modeling, as she has done part-time all through college. Modeling is rewarding, she says. But she has distanced herself somewhat from it, after some of the scenes she says she's witnessed as a teen. She remembers being told to stop running, despite being on sports teams, because of how it would make her legs look, and going into castings and being told, “The last girl just fainted in here—you’re not going to faint today, right?” Those restrictive, dangerous standards for women’s bodies are “toxic,” she says.

Now, she says, she would rather work with companies that show off all kinds of bodies, ones that allow her “to continue showing up as my full self, as someone who is a researcher and also someone who has modeled for some time,” like Rebecca Minkoff, whose I Am Many feminist collective campaign Greco has been a part of for years. The wounds of economic inequality, of exclusion, of violence to women’s bodies, of self-doubt—they’re questions Greco continues to try to answer. Studying the world and trying to repair it is slow and frustrating work, but it’s rewarding. “I think it’s really beautiful to be able to watch things heal,” she says. —J.S.

Kristen Busch

University of Chicago

Within the first few months of the pandemic, it became clear that COVID-19 would not be a great equalizer. True, in a vacuum, it could afflict the rich and poor, white people and people of color, men and women, in equivalent numbers. But it doesn’t.

Instead, the virus has had a disproportionate impact on minorities and marginalized communities—on Black Americans, on immigrants, on incarcerated people, on low-wage workers, and on people with physical challenges.

Kristen Busch, 21, has been working with individuals with disabilities since middle school. She was a tutor for students with disabilities and grew close with some of her tutees. In high school she counted one of them as a close friend; that friend came down with the flu and died from complications. “For me to see the ableism and the stigma that surrounded her death, because of her disabilities,” Busch says, “that was really the catalyst for me to get more involved in the movement.”

Busch has since thrown herself into it. Relatives have acquired disabilities, and she’s supported them in navigating that. But she’s also come to understand on an intimate level how lacking policies are around disability justice. “It's pushed me to continue with this and make it my lifelong work and passion,” she says. “I really believe that it's essential that we put disability issues of access and equity at the forefront of all of our conversations, because it does impact everyone, whether it be you or your family members or your friends or loved ones or coworkers. All of us are impacted by disability at some point in our life."

With two other women at the University of Chicago, where Busch will soon start her senior year, she formed the nonprofit Open Access to combat disparities facing special education students in Chicago. In 2018, just as she was moving to Chicago from her native Minnesota, there were major budget cuts in special education, which led to students being denied services. “They weren’t able to get buses to schools. They weren’t able to get time with specialists,” Busch says. Her organization helps students and their parents mobilize through online resources and workshops. In a pandemic, which is exacerbating issues of access, that work is particularly relevant. “It seems like the message from the federal government is that we’re [willing to] leave students with disabilities behind, if schools just can’t manage it. I think the pandemic at large is showing how we do or don’t value people with disabilities and disabled children in particular.”

Busch also works as a research assistant, exploring the obstacles that people with disabilities who are incarcerated face, and she’s been exploring international solutions to some of these problems, looking into what America can learn from countries around the world. (She was recently named a Truman Scholar, which comes with a scholarship to help her continue in that research.)

Still, she comes to the work with the awareness that she is an able-bodied person. She looks up to activists like Alice Wong, who runs the Disability Visibility Project, and Sins Invalid, a performance project that celebrates and centers artists with disabilities. “As a white woman working in this space, I'm constantly rethinking what my role is in the movement,” she says. “How do I stand in solidarity and support the work of disabled people and raise their voices versus putting myself at the center? The mantra of the disability movement is ‘Nothing about us without us.’ So whenever I enter a space and try to push for equity and access, I think about that and think about reconciling the privilege I have with the work I want to do.”

That internal reckoning has driven Busch to reevaluate how she shows up for other movements too—and the place that she sees for herself within them. “Being a woman working in this space has challenged the feminist idea of an independent woman, of that being the ultimate goal,” she says. “In working in disability justice, you realize, no, it’s all about interdependence. You don’t have to be independent to be strong or to be a feminist. You don’t have to be independent or manage everything on your own, and I think there’s a lot to learn from that.”

Busch also thinks the disability justice community has lessons to offer those thinking about structural change for perhaps the first time, as allies in particular. It teaches that there is no one way to engage with activism or organizing. “You can be mobilizing and organizing people from your bed, from your wheelchair, from your couch at home,” she says. “People with disabilities have been figuring out how to organize remotely for years. I think people are realizing, ‘Wow, we have so much to learn from this community. And there's so much value here that just hasn't been recognized before.’”

Busch is now developing a research project, looking at how the pandemic has affected disabled living facilities, which have gotten less attention than nursing homes or other long-term care facilities. “This crisis has magnified the disparities that have existed in our society for a long time, whether that’s systemic racism, as we’ve seen with the George Floyd protests, or other forms of discrimination. I see it as a my responsibility to think about that every day, and then do the work to change it.” —M.K.

Christina Morales

University of Florida

There are on-campus jobs that help bills get paid, and then there’s the full-on career that Christina Morales embarked on as a student at the University of Florida.

A journalism major, Morales, 22, didn’t just take classes on reporting or editing; she worked in a full-fledged newsroom, becoming editor in chief of the Alligator—her campus’s student newspaper—as a senior. This spring, the Alligator broke news statewide when it reported that four U.F. students had tested positive for COVID-19. Morales later told the Washington Post that she could see demand for the newspaper’s coronavirus stories leap up in real time. At one point, user interaction with the Alligator’s Facebook posts was up 602%. These are the kinds of stats that Morales monitored before…finishing a term paper.

Morales grew up in Hialeah, Florida, and settled on journalism as a possible career in high school because it would fulfill her childhood dream of writing full-time. But once she settled into her classes at U.F., she came to appreciate other aspects of the discipline: First Amendment protections, the thrill of getting out and talking to people, and the crucial impact that journalism can have on, as she puts it, “communities like mine.”

“It’s become more and more for me about how reporting can shape communities, how I can help communities with the reporting I do.”

The conversations that the media is having now about the importance of a diverse newsroom are ones Morales has been pushing since she arrived at the Alligator and in particular as she climbed its masthead. “I feel like there are a lot of stories that diverse people can help tell,” she says. “And I mean, ‘diverse’ in a range of things—race, background, gender, age. For us at the paper, it was also about majors.” At other news organizations, it might involve hiring veterans or people with disabilities. Morales recognized that the more diverse her staff—the broader the range of voices—the better the paper looked each morning: “We ended up with stories I might never have considered were it not for that one reporter or that person.”

She has also experienced firsthand, as a reporter herself, the advantage of a perspective that isn’t the “norm.” At an internship with the Oregonian, Morales realized she was one of the few people on staff who spoke Spanish. Her editors started sending her out to talk to Spanish-speaking immigrants who worked in the state’s farming sector. She did one piece, then two; soon she had, in essence, kicked off a one-person immigration beat. Morales produced stories she’s proud of—nuanced, rich with detail. She realized during that internship that if it weren’t for her, it’s possible no one would have written them. That is the value of a newsroom with lots of different kinds of people in it—it gives an outlet the chance to tell the best and most expansive stories.

Now Morales says, “I think a lot about the impact that I made there, which I didn’t see at the time: I was able to help people.” It’s an experience she comes back to, informing the central question of her work: “How can I do reporting that uses my perspective as a daughter of immigrants, as someone who is a member of the Hispanic-Latino community? How can I use that perspective to further my reporting?”

At the Alligator, Morales found several answers. She cultivated her reporters, encouraging them to pursue the stories that mattered most to them. She pushed her staff to think of the newspaper as a resource in the middle of a pandemic that had derailed their lives too—and saw the reader response in real time. “I’ve never seen so many people on our Facebook page or on our stories,” she says. “Getting this information out about the coronavirus, breaking it so fast. That was big for me.”

Morales remained in her off-campus apartment in Gainesville through the onset of the pandemic and through graduation. The experience blurred the line for her between her work and her life. “As reporters, we’re always trying to separate ourselves from the story,” she says. “And during the pandemic, our newsroom became itself a part of the story. Our classes were canceled, and we were reporting on that. Our graduation was canceled too, and we had to report on that while people figured out whether they needed to go home. It was my call to say, ‘Don’t even come to this newsroom anymore. I don’t want anybody to come in and get sick.’ I had to come up with plans to do this remote work, with people working from all across the country.” How do you report on something that’s affecting every single aspect of your life?

Morales just started a fellowship at the New York Times and has been thinking a lot about what Times executive editor Dean Baquet said in a recent interview. “He said something like, ‘Objectivity is being able to walk out of the office with an open mind, knowing your story could go anywhere.’ So I do come in with this perspective, but when I walk out, I can go, ‘Okay, I’m going to have an open mind about this.’” —M.K.

Rachel Junck

Iowa State University

Starting a new job has its challenges, but starting a new job in an elected office while also a full-time student in the middle of a pandemic presented particular obstacles for Rachel Junck.

Junck, who attends Iowa State, majoring in chemical engineering, won her seat on the Ames City Council in December. She was 20, with no previous experience in local government. Still, as Junck points out, she was born and raised in Ames—she’s been an observer of the area’s problems and opportunities since birth. She defeated an incumbent who was seeking his third term.

The campaign was historic—Junck is now the youngest person elected to any office in Iowa history. But of course, she couldn’t have known then just how historic her first term would be.

“There is a learning curve, being new, having a lot of material thrown at you at once,” Junck recalls of those first few weeks in office. “And then three months in, having the pandemic hit and our council meetings go online was just another kind of curveball. Making decisions about COVID-19 in Ames and thinking about how to keep people safe was definitely something that I never could have imagined would have been in the job description.”

When Junck did decide to run for office, she ran on three central issues. First, she wanted to get serious about tackling climate change. Second, she emphasized affordable housing, not just for those seeking to purchase a home, but for renters. Ames draws a huge student population, because of Iowa State. Junck felt local leaders were ignoring her peers, even as Ames retailers count on them. And third, Junck wanted to promote Ames as an inclusive place to live; she wanted it to reflect the values with which she was raised. “I wanted to be able to ensure that everyone would feel welcome here, especially students looking to settle down,” she says. “I would hope that more people would consider staying in Ames to build their families and their careers here as well, because it’s a great place to live.”

Dealing with a public health crisis was not on her list of campaign priorities, and she is the first to concede that it has thrown a wrench in her first term on the council. But it has also, she thinks, given her the chance to prove herself to her constituents. “We live in a town where half of the population is students, and before me, there wasn’t a student with a vote on the council to represent our interests,” she says. “That pushed me to run and be able to represent those who hadn’t had a voice before.”

Now that voice is even more valuable, as Ames—like cities and towns nationwide—figures out how it will reopen amid the pandemic. Her role on the council has deepened her appreciation for local government, which is as responsible for the day-to-day lives of its citizens as the federal government is. It fell to the council to decide whether or not to open the municipal pool this summer, how to celebrate larger events, what to do in the event of an outbreak. “Students who thought, Oh, this race doesn’t affect me at all, see now that it does affect the parking regulations on the streets where we live,” Junck says. “It affects all the roads that we drive on. It affects how budgets are allocated and the kinds of activities and events that are offered in Ames.”

Junck insists that campaign season took a greater toll on her schoolwork than serving on the council does. Now she balances preparing for council meetings with her chemical engineering courses, reading budget materials and briefs while school was in session on nights and weekends. Whatever the impact on her social-distanced classes or the remote engineering internship she’s doing now, the trade-off for Junck is worth it.

“I had always had an active interest in improving my community and being politically engaged. But I had never really thought that I would run for office until a lot of students talked to me about it,” she says.

“There were a lot of people that I did have to prove myself to as a capable and knowledgeable candidate,” she says. “And a lot of people were skeptical that I had the same amount of expertise to offer as some of the older people running for office.” Still, she won them over. And if she can convey one message, it’s that other people who are still in school or have been told that they’re “too young” to lead can too.

“There are so many different things that people want to see improved or things people believe we could do better in Ames,” she says. “Some of them were right along the lines of my campaign issues like affordable housing. But there are smaller things too that every one of us can advocate for—making bike paths more accessible, making our parks safer, adding signs and lights to roads. Things like that, small things can really improve people’s everyday lives.” —M.K.

Rebecca Smith

Rebecca Smith

La Salle University

Rebecca Smith was in a maximum-security prison when a person living out a life sentence pointed at her and said that she reminded him of someone.

As part of La Salle's honors program, which Smith's impeccable academic record has qualified her for, semester after semester, she took a business ethics course that involved service learning. It was through that program that she found herself visiting a maximum-security prison with her class, attending a daylong think tank with people who are imprisoned for life. And it was there that a man living out a life sentence pointed at her and said that she reminded him of someone.

“He told me he thought his niece would have grown up to look just like me,” she says.

The comment struck her—not that he was singling her out or that he was making a comparison between herself and his family member. It was the word thought.

“He thought,” says Smith, emphasizing the word. “He hadn’t seen his niece in eight years.” The fact of the prison system, and of life sentences—that it forces people to experience their own family members not as evolving people but as ideas—hooked into her. She couldn’t stop thinking about the children of people who are incarcerated: children whose parents disappear, for months or years, only to walk back into their life. Children whose parents disappear and never come back. Children trying to come to terms with the fact that their parents are not dead but somehow unreachable.

Smith is a doer—she was recruited to La Salle University to play on the school’s Division I golf team. She ended up serving as captain for three years. She was a member of the Gamma Phi Beta sorority. She worked, throughout college, as a campus tour guide, showing prospective students and their families around the Philadelphia school’s grassy urban campus. And so the 22-year-old did what she tends to when she can't stop thinking about something: She searched for answers.

Smith went looking for resources for these children—this class of tiny people who grow as fast and as inhumanely as America’s ever-expanding prison system. “There’s not very much on the market,” she says. She wanted to make a contribution. “I thought what better thing to do than create a children’s book to help children not feel ostracized or alone and know it’s a much more common process than people realize,” she says. When Smith was a child and a family member went through a difficult illness at a young age, she says, there were no books to comfort, or to help to confront the reality of the situation. Children's books can be extraordinary tools, but even among the crop of socially aware picture books of the last few years, not every stigmatized situation gets bound into a beautiful book. “There’s plenty that tackles the loss of a pet or divorced parents,” says Smith. “But there was nothing really that was talking about incarcerated people, or the idea of a father going away and then coming back, the reentry process.”

And so Does He Still Love Me? was born. Smith’s picture book started with tons and tons of research—reading studies and doing personal interviews with people who have been affected by a family member’s incarceration. She interviewed students at her college who had experienced a parent’s incarceration. She interviewed people in the community whose spouses had been incarcerated.

She spoke to elementary school teachers in her home state of Indiana, who were confronting these issues on a regular basis. “Just realizing how a public school teacher might have six or seven children in their classroom who have one or more incarcerated relatives was really eye-opening to me,” Smith says. Does He Still Love Me?, which Smith wrote, illustrated, and published as a senior at La Salle, is for those kids—and for their classmates. “No one should be ostracized because of what their life is like at home,” she says. The message of the book—which follows the experience of Thomas, whose dad is incarcerated—is that his dad loves him and that his dad’s situation is not Thomas’s fault.

The book came out in February 2020. While the pandemic has disrupted some of her plans to share it with the wider world, she remains undeterred. She is donating all 2020 profits from the book to Turning Point, a domestic violence services center in Indiana, and she donated copies of her book to her local shelter, where she had planned to visit and read to children. When children return to school buildings, her books will be there. “I would really like to be able to share this book with as many children as possible,” she says.

Beyond that, Smith has a dream of becoming a commercial airline pilot. She plans to start training when the pandemic allows for it. “I’ve wanted to do it since I was like 12, and I realized I couldn’t talk myself out of it,” she says. “I’m signing myself up for a life of adventure and excitement.” —J.S.

Jenny Singer is a staff writer at Glamour. You can follow her on Twitter.

Mattie Kahn is the culture director at Glamour.

Originally Appeared on Glamour