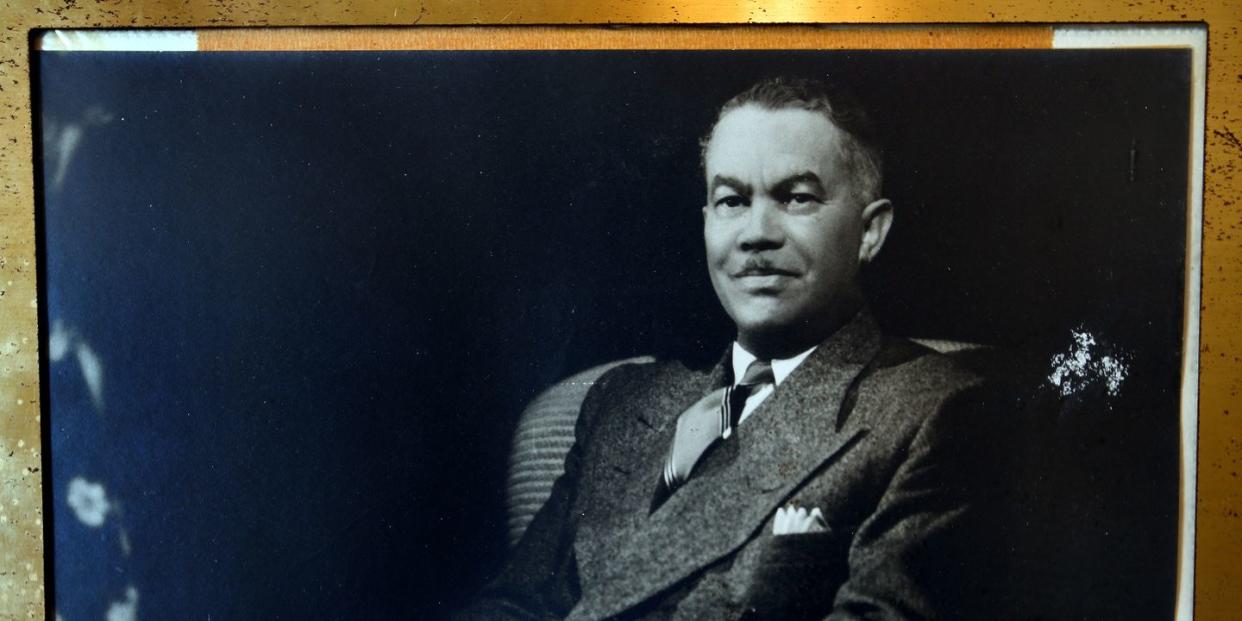

Meet Paul Williams, the Trailblazing Black Architect Who Helped Define Los Angeles

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you’ve ever marveled at the glamorous mansions that line the posh streets of Los Angeles, you’ve likely admired the work of Paul Revere Williams. The first African American to become a certified architect west of the Mississippi, the pioneering draftsman had a hand in designing many of L.A.’s most iconic buildings, including parts of Los Angeles International Airport and the Beverly Hills Hotel—not to mention the homes of many Hollywood bigwigs—including Frank Sinatra, Carey Grant, and Lucille Ball—which earned him the nickname of “architect to the stars.”

But what makes Williams so legendary? It’s not because by the end of his five-decade career he had designed more than 3,000 buildings, or that he designed the glamorous abodes of countless celebrities. It’s because he served as a champion and voice for minorities during an era when racial discrimination was still rampant in America, paving the way for every other Black creative who followed in his footsteps.

“The power of example is strong,” Williams penned in his 1937 essay for American Magazine, I Am a Negro. “A few decades ago Negroes had no examples within their own race to spur them on. But now, seeing men and women of their own color bettering their condition so phenomenally, they realize that they—or their children—can do as much.”

Despite Williams’s efforts, only about 2% of all architects in the United States identify themselves as Black, according to a study published by the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards. Nevertheless, his contributions to the architectural world and the Black community have cemented him as one of the most influential Americans of the 20th Century.

Who Was Paul Williams?

Paul Revere Williams was born on February 18, 1894, into a middle-class family in Memphis. He was tragically orphaned at the age of 4, losing both his parents to tuberculosis, and was sent to foster care until he was adopted. After studying at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and at the L.A. branch of the (now defunct) New York Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, he worked as a landscape architect, later earning a degree in architectural engineering from the University of Southern California. He married Della Mae Givens in June 1917, and together they had three children (the eldest of which passed away at birth).

In 1921, at the age of 27, he became a certified architect, going on to open his own firm the following year. In 1923, he became the first African American inducted into the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

Williams, who served as an architect in the Navy during World War II, was known for his uncanny ability to draw upside down—a skill he taught himself for the benefit of white clients who might have felt uncomfortable sitting next to the Black architect. For the same reason, he made a habit of keeping his hands clasped behind his back, so that no client would ever feel obligated to shake his. Though he was often subjected to blatant racism and marginalization, he never allowed it to rattle him, nor get in the way of his work.

In his words, as penned in a 1937 essay published in American Magazine, titled I Am Negro: “I came to realize that I was being condemned, not by lack of ability, but by my color. I passed through successive stages of bewilderment, inarticulate protest, resentment, and, finally, reconciliation to the status of my race,” he shares. “Eventually, however, as I grew older and thought more clearly, I found in my condition an incentive to personal accomplishment, and inspiring challenge. Without having the wish to “show them,” I developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself.’ I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, as an individual, deserved a place in the world.”

What did he design?

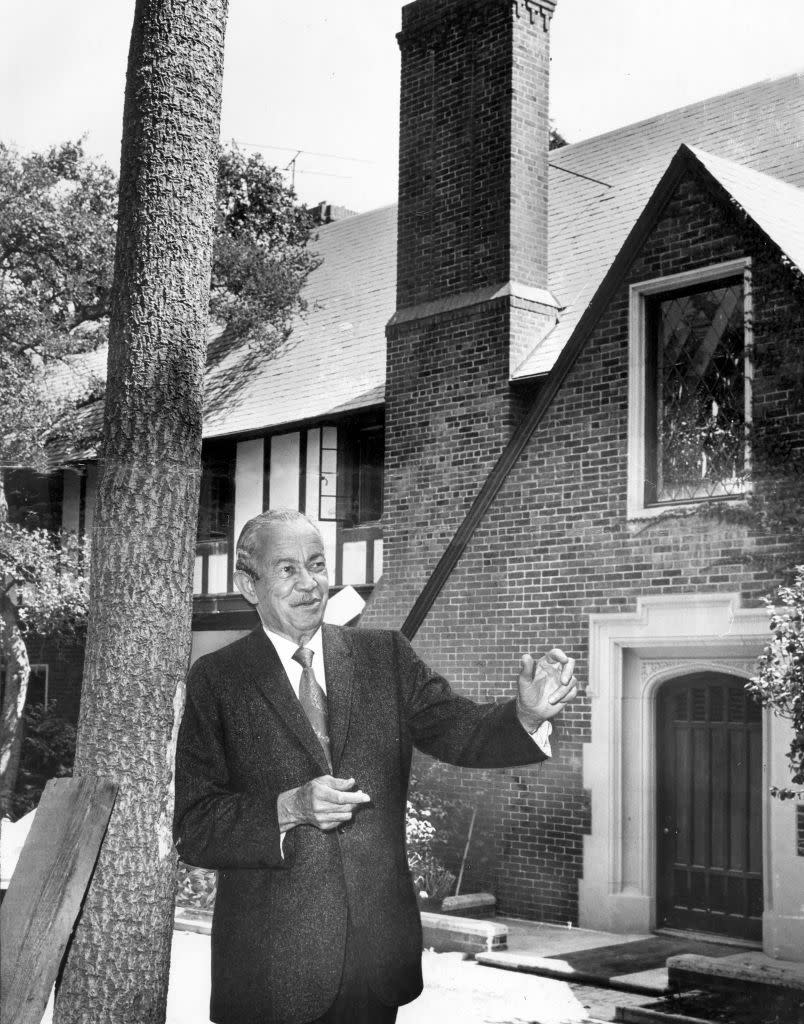

Williams is responsible for the creation of more than 2,000 private residences, including Sinatra’s former hilltop estate on Bowmont Drive, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s sprawling home in Palm Springs, and French restaurateur Rene Faron’s American Colonial-style abode in Silver Lake, CA. Among his most prominent public works are the Golden State Mutual Life building in L.A., St. Jude Children’s Hospital in Memphis, and the Los Angeles Superior Court. The mastermind behind Saks Fifth Avenue’s Beverly Hills store, he also spearheaded the revamp of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel—an extensive renovation that cost $3 million. He similarly oversaw the transformation of the Beverly Hills Hotel, anchored by the addition of the $1.5 million Crescent Wing.

Projects outside of Los Angeles included remodeling numerous buildings and spaces for Howard University (including the halls that house the men’s dormitory, dentistry school, and architecture and engineering college), as well as designing two hotels in Colombia (one in Medellin—the other, in Bogota).

At one point, he helped fellow architect and friendly rival Wallace Neff draw plans for a mega development in Las Vegas that would contain 1,000 Airform structures—small, hardy prefab homes that would cost little time and money to construct. And two Nevada tech companies, Lockheed and Guerdon Industries, later asked him to help develop a car-alternative transportation system, prompting the architect to design the SkyLift Magi-Cab, a futuristic monorail (Unfortunately, neither project was ever realized.)

Regardless, Williams single-handedly shaped much of the modern-day urbanscape, leaving an indelible mark on the West Coast. The legacy of the trailblazer—who passed away from diabetes in 1980 at the age of 85—lives on not only through the structures he built, but also through those who continue to carry on his aim of helping fellow aspiring Black creatives and professionals achieve their dreams.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

You Might Also Like