Meet the Downtown Gallerists Trying to Make the Art Scene Less Wack

For Pascal Spengemann, who opened the new gallery Broadway with business partner Joe Cole in October, the decision to hang his shingle during the covid era came down to a need many New Yorkers felt after a six month museum and gallery closure: “I’m, number one, very excited to be in a room with artwork again,” Spengemann said. So were a dozen or so people who arrived at the Tribeca space (located on, of course, Broadway) on a recent Saturday for the opening of the gallery’s show of Meg Lipke’s monumental, sculptural canvases, a number that eventually required Spengemann to apologetically enforce an occupancy limit.

In good times, galleries exist in a ruthless market. Covid has blown up whatever little predictability there was—with the suspension of art fairs and a months-long ban on indoor viewing that appears likely to go back into effect in the coming weeks, galleries of all sizes have battled for survival. The storied Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, for one, closed for good as Brown went to the larger Gladstone. Many others have followed the collector class to Los Angeles or Miami for the winter, or relied on a combination of online viewing rooms and sympathetic landlords to stay afloat.

And yet, in the wake of the dramatic implosion of Chelsea mainstay Marlborough Gallery, three of that gallery’s alums have established new spaces that point toward an exciting trend: an art world populated by risk-taking galleries, operated with a human touch. A revolutionary concept? Not exactly, but when we stopped by these three galleries in the past month, it was hard not to feel optimistic that what’s next for the art world looks a lot like the community-building being done in Tribeca, the arrival of art on St. Marks Place, and a hyper-independent project in Chinatown.

For Spengemann, a former vice president of Marlborough Gallery, and Cole, a collector and businessman, the goal is to establish a place friends and strangers alike can hang out at, at least after the pandemic—an atmosphere you don’t often find in the relatively icey blue chip Chelsea galleries they once inhabited. “For me it’s pretty important that the vibe is right—that it can be a place where people can come in, start a conversation,” Spengemann says. “The big galleries in Chelsea sometimes feel like an extension of the high line, but we want to be much more part of the neighborhood.” At Broadway they’ve picked up a tip or two from the homiest retail stores—beers and, crucially, merch are on offer, specifically excellent hats made by Spengemann and his frequent collaborator Andrew Kuo that look pilfered from a Little Italy souvenir shop.

Marlborough, which once represented Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, and which more recently was home to a roster of buzzy young artists like Kuo, spherical sculptor Lars Fisk, and avant-garde collaborators Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe, was poised to become the next Chelsea mega-gallery before it was derailed by a series of internecine lawsuits. During his tenure there, Spengemann helped build out the gallery’s emerging talent bench, and at Broadway he’ll be bringing some artists with him, as well as working with friends who didn’t fit into Marlborough’s programming. (The Lipke show, which features the Hudson-based artist’s Seussian paintings, is the culmination of a 20-year friendship.) “We can do whatever we want here, and that just wasn’t the case at Marlborough because there was higher overhead, and more cooks in the kitchen. Certainly we got to do a lot of exciting stuff there, but now we can try more things,” Spengemann said.

One such show marked the gallery’s debut: an exhibition by the Ho-Chunk nation artist Sky Hopinka, anchored by a 16-mm short film installation. (It was a hit: Times critic Holland Cotter says Hopinka’s work at Broadway—and a concurrent survey at Bard—“rivals in visual and linguistic beauty any new art I’ve seen in some time.”) A sprawling group “homies” show featuring friends of the gallery like Devin Strother, Adrianne Rubenstein, Andrea Marie Breiling, Kuo, and many more is next.

Opening a gallery during a global pandemic is not without its difficulties. “The challenge is getting the collector base through the door,” says Spengemann, noting that many fled the city in the spring and tend to be on the older side. But the Palm Beach class is still buying—even this year’s mostly online Art Basel saw healthy action. “I think the art market, versus something like retail, is getting through this,” said Cole.

The most notable thing about Leo Fitzpatrick’s new gallery, aptly named Public Access, might be its location: a basement space on not-particularly artful St. Marks Place. Fitzpatrick, the actor whose breakout role as Telly in Larry Clark’s Kids thrust him into downtown fame at the tender age of 17, joined Marlborough in 2015 to organize experimental shows with the gallery, before leaving earlier this year. On a recent Friday evening, Fitzpatrick surveyed the scene—raucous outdoor diners, teenagers slouching eastward—and noted that it hadn’t occurred to him until recently that it was even possible to open a gallery on the legendary (if somewhat Disney-fied) stretch. “In my 25 years of hanging out on St. Marks, there was never a gallery,” he said. Planting his flag in the neighborhood he’s long called home didn’t come down to convenience or price but a decision that his gallery would stand apart from the mainstream art world: “The street,” Fitzpatrick said, “is dictating the type of stuff I want to show.”

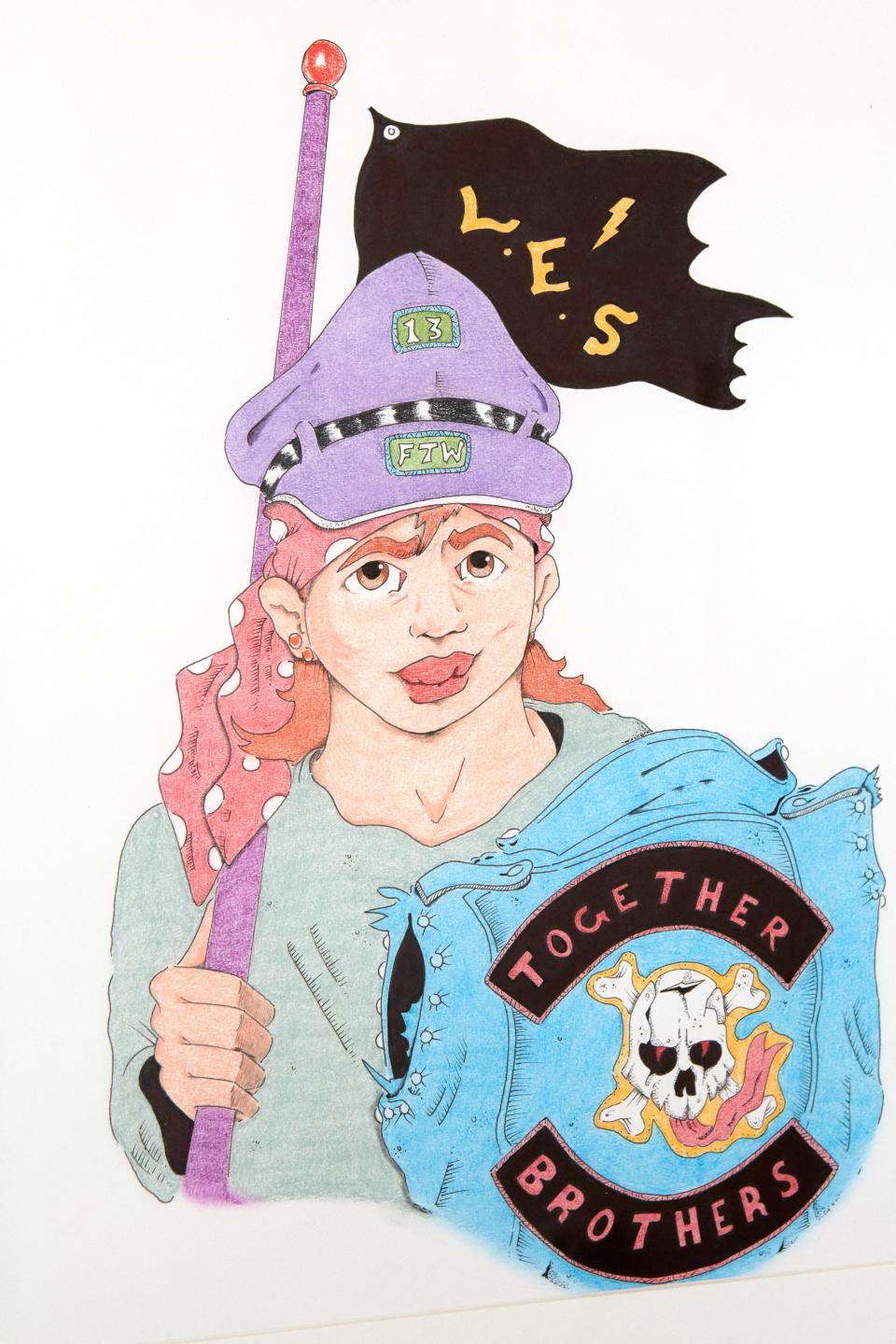

Which is why on this night Fitzpatrick and Jose “Cochise” Quiles were waiting for a vanload of young gang members to pull up. Cochise, a stocky fellow wearing a motorcycle jacket and Gadsden flag trucker hat, is not your typical gallery artist. A former member of the Lower East Side street gang Satans Sinners Nomads, Cochise served 18 years in prison for attempted murder after stabbing two of his fellow gang members and tossing them in the East River. (Both survived.) Before going to prison, he made dark, outlaw-biker art in the gang’s clubhouse that got noticed by the likes of GG Allin and Dash Snow, but while incarcerated, he began creating caricature-style portraits of fellow inmates, which they would send to their children. Upon release, he made it his life’s mission to give kids an alternative to gang life, which is why the members of the Almighty Black P Stone Nation and Rolling 30 Crips were coming to the gallery—to check out his intuitive and lush portraits of historic gangs, paired with crisp histories of their brutalities and downfalls.

“I’ve never had a solo show—Leo was the only one who came up to me and said, Cochise, I could give you a solo show,” Cochise said. “And I appreciated that, deeply. I believe that with art you can help transform a life.” In his own way, Fitzpatrick is trying to speak to the kids who might stumble in off St. Marks, even if to catch a glimpse of a grey-haired Telly: “I want to show kids that art is a big umbrella,” he says. Accordingly, the gallery’s debut show was a collection of airbrushed custom skateboards made by skate legend Mark Gonzales. “We’re not trying to be the average gallery that is trying to show the hot young artist—we’re showing people that typically don’t show, but are comfortable with me,” Fitzpatrick said. Ironically, the smaller platform has expanded the list of artists he can work with. “Coming from Chelsea there were a lot of artists who wanted to show with me, but didn’t want to show where I was working. It’s not on the same scale, but big and small artists understand that’s ok. They’re artists.”

With his price points topping out at $1,000, Fitzpatrick acknowledges he’s barely breaking even. Which isn’t really the point. “Why do I enjoy this? Because I really enjoy this type of stuff,” he said, gesturing at the leather-clad outlaws smoking outside. “I don’t know what these kids are gonna be like, but it’ll be better than a gallery opening in Chelsea, that’s for sure. I always hated that shit.”

Over in Chinatown, an artist once represented by Marlborough, Tony Cox, has shaped his secretive apartment space into one of the hottest tickets in town. It’s called Club Rhubarb. The name, Cox says, comes in part from the unofficial title of the song he would choose to die to: track #3 on Aphex Twin’s 1994 album Selected Ambient Works Volume II. “Club” comes from the fact that it throws people off from the project’s purpose. “I wanted something that people didn’t associate with dadada projects or dadada gallery,” he said on a Saturday morning in November. “People are very confused about what it is.”

It is, to be clear, a gallery, one that’s showing an excellent exhibition of recent works by San Francisco psychedelic warrior Joe Roberts. After showing his own work with Marlborough, Cox became disillusioned with the mainstream gallery system, and decided to help artists that were being overlooked by the gatekeepers of the industry. “I wanted to focus on showing artists that deserve a platform but that the art world doesn’t normally pay attention to,” he said. Roberts is one such artist who “surpasses the box people want to put him in.” A Supreme collaborator also known as L.S.D. World Peace, Roberts’s dreamscapes are inhabited by aliens, superheroes, and the occasional pair of Cactus Plant Flea Market x Nike Blazers. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Roberts’s second solo show in New York has received interest from “kids,” as Cox described them, as far afield as Florida.

But entry to Club Rhubarb does require a secret handshake of sorts, and the Floridians didn’t know it. The address is unlisted (Cox asks visitors to keep it a secret and not post any identifying details on Instagram), and Cox screens inquiries from strangers by asking them questions about their relationship to the work. “I want it to be a special thing,” he said. “150 people have seen the show, and all of them are people who really should’ve seen the show. Which to me is way more effective than 1,500 people who are there because it’s what everyone is talking about.”

Which is why, despite recommendations from friends that he establish a permanent, street-level gallery space, Cox remains committed to his cubbyhole. In fact, Cox sees what he’s doing not as some weird aberration but as the direction the art world is—or at least ought to be—going. “The other ways of showing art are dying out,” he said. “That’s why I started this thing. I wanted to eliminate all the people who made the art scene wack—they’re not allowed in. I only want good energy. That’s what art’s supposed to do. It’s supposed to make you feel good.” It’s been working: almost all of Roberts’s work sold as soon as Cox hung it on the wall.

Despite the drama of Marlborough’s demise, the three gallerists remain close within the dysfunctional family that is the tight-knit downtown gallery scene. With the specter of another lockdown looming, it’s anyone’s guess what that scene will look like by the time we’re all vaccinated. But for now they share an ethos appropriate for the era, one articulated by Fitzpatrick when asked about the challenges of opening an unorthodox gallery in 2020. “I’ve never known how to do it the right way,” he said, “I’ve only known how to do it my way. And if I’m going to fail, it’s going to be in a spectacular fashion.”

Originally Appeared on GQ