Haunani-Kay Trask, Kiyoshi Kuromiya, Rushan Abbas And 5 More AAPI Activists That They Didn't Teach You About In School (But Should Have)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, BuzzFeed has featured eight API American activists to highlight the history, contributions, and perseverance of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in the US:

These eight API activists include, in chronological order:

• Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896–1966): Chinese and American women's rights activist

• Philip Vera Cruz (1904–1994): Filipino American labor leader, civil rights activist, and farmworker

• Edward Said (1935–2003): Palestinian American scholar and Palestinian independence activist

• Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943–2000): Japanese American civil rights, anti-war, gay liberation, and AIDS activist

• Haunani-Kay Trask (1949–2021): Native Hawaiian rights and Indigenous rights activist, scholar, author, and poet

• George Helm (1950–disappeared 1977): Native Hawaiian rights activist and musician

• Rushan Abbas (1967–Present): Uyghur American human rights activist

• Manjusha Kulkarni (1969–Present): Indian American human and civil rights activist and attorney

You can read more about each activist, their work, and their legacies below.

1.Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1896–1966): Chinese and American women's rights activist

Early Life, Immigrating to the US, and Education

Born in Guangzhou, China in 1896, Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee came to the US at age 9 after winning the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, an academic scholarship that granted her a US visa and allowed her to attend school in the US. Her father, Dr. Lee Towe, a missionary, had moved to the US five years prior and served as the Baptist minister of the Morningside Mission in Chinatown. At 16, Lee was accepted to Barnard College, a prestigious women’s liberal arts college founded as a response to Columbia University’s refusal to admit women.

Leading the New York City Suffrage Parade

In 1912, 16-year-old Lee joined a suffrage meeting held in Chinatown with other prominent members of the Chinese community. There, she met with well-known white suffrage leaders, including Harriet Laidlaw, Anna Howard Shaw, and Alva Belmont Vanderbilt. Lee explained the intersectionality of sexism and racism that Chinese women face in the US and pushed for more equitable educational opportunities for Chinese children in New York City.

Impressed by Lee, the white suffrage leaders asked her to help lead a parade they were planning in New York City. She'd already been reported on by the New York Tribune and the New York Times for her activism. Lee accepted and led the parade on horseback. White suffragists, particularly Anna Howard Shaw, carried a banner during the parade that read, “NAWSA Catching Up With China,” to publicize that the US was “behind” China in voting rights.

Student Activism and Suffrage in the US and China

During her time at Barnard College, Lee continued to stay active in women’s rights conversations in both the US and China. She was heavily involved in the Chinese Students’ Alliance, a national organization of Chinese students studying in the US, and wrote articles for their journal, The Chinese Students' Monthly. In her articles, she called for the future leaders of China to incorporate women's rights into the new republic. In one such article, “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage,” Lee questioned whether the nation would “build a solid structure” that included women’s rights from the beginning or “leave every other beam loose for later readjustment,” drawing upon her American suffrage experience.

Though Lee was primarily asked to update white suffrage audiences on women’s rights in China, she also focused on advocating for the rights of Chinese students in America. In 1915, the Women’s Political Union invited Lee to speak at one of their Suffrage Shops. She gave her speech, “The Submerged Half,” calling for the Chinese American community to promote girls’ education and women’s participation in civic life.

The Right to Vote and the Status of Chinese Americans

In 1917, the state of New York granted women the right to vote. Two years later, Congress passed the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote federally. However, due to the Naturalization Act of 1790 — which declared that only people of white descent were eligible for naturalization — Lee and other non-white immigrants were unable to become citizens and therefore still unable to vote. In spite of this, Lee remained committed to her cause. In 1921, she became the first Chinese woman in the US to earn a doctorate degree in Economics from Columbia University.

A few years later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which effectively banned all emigration from Asia by setting immigration quotas and forming the US Border Patrol to restrict the flow of illegal Chinese immigration. During World War II, Japanese propaganda targeted this act and encouraged China to break its alliance with the US due to racist laws. In part due to this propaganda, the US enacted the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943, which allowed limited Chinese immigration and permitted some immigrants to become naturalized citizens. However, the act still denied Chinese immigrants and citizens property-ownership rights.

Later, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 abolished the “alien ineligible to citizenship” category from US immigration law, which only applied to Asian people in practice; however, there still existed Asian immigration quotas. In fact, it wasn’t until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that the Immigration Act of 1924 was fully repealed.

Staying in the US and Community Impact

While many Chinese women returned to China after studying in the US due to limited opportunities, Lee remained and eventually took over her father’s role as director of the mission, which became the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City, upon his death. She continued to advocate for her community and went on to found the Chinese Christian Center, a community center that offered vocational and English classes, a kindergarten, and a health clinic.

Legacy

In 1966, Lee died at age 69-70. On December 3, 2018, a Chinatown post office at 6 Doyers Street was named after her. On top of mobilizing the Chinese American community to support women's voting rights, Lee advanced education and healthcare for the Chinese American community in New York.

2.Philip Vera Cruz (1904–1994): Filipino American labor leader, civil rights activist, and farmworker

Immigrating to the US and Poor Labor Conditions

Born in the Philippines in 1904, Philip Vera Cruz came to the US in 1926, having told his mother he’d only stay for three years. After working numerous odd jobs, Vera Cruz was drafted for World War II in 1942 and sent to basic training in San Luis Obispo, California. Due to his age — he was in his late 30s — he was discharged and assigned to agricultural production to support war efforts. Vera Cruz moved to the town of Delano, where he labored as a farmworker for 9 to 10 hours a day at 70 cents per hour in 100–110ºF weather. Living conditions were similarly bad as farmworkers lived in labor camps with outdoor toilets, showers, and kitchens and received no healthcare, benefits, or rights.

First Strike and Early Activism

In 1948, Filipino farmworkers organized a strike in response to poor wages and working conditions in Byron, California, which spread throughout the Stockton area. This was Vera Cruz’s first strike and a milestone for Filipino workers in the US. In the 1950s, Vera Cruz joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), comprised mostly of Filipino farmworkers, where he served as the president of the local chapter in Delano. Noticing the NFLU's organizing efforts, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) created the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) in 1959, which Vera Cruz also joined. Early AWOC organizers included Filipino labor leader Larry Itliong and Mexican American labor leader Dolores Huerta, who later left AWOC for the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), predominantly comprised of Mexican workers, with Cesar Chavez.

The Delano Grape Strike and Birth of the United Farm Workers Union

In 1965, Filipino farmworkers in Coachella, who were also members of AWOC, began to strike, demanding a wage of $1.40/hour — a 10 cents/hour increase. Because it was the beginning of the harvest season, Coachella growers quickly conceded. However, as Delano — which was further north — reached its harvest season, Delano growers refused to match the new Coachella wages. On September 8, Filipino farmworkers, as members of AWOC, met at the Delano Filipino Hall and voted to strike — a significant decision in the history of farmworker labor.

Lasting for five years, the Delano grape strike came to include the NFWA, as Filipino and Mexican labor leaders decided to strike together, leading to the merging of the AWOC and NFWA in 1966. The resulting organization, the United Farm Workers Union, was led by both Mexican and Filipino labor leaders, including Vera Cruz and Itliong. As such, Vera Cruz traveled across the country to garner support for the strike, encourage a boycott of non-union grapes, and recruit new UFW members. Though initiated by Filipino farmworkers, the Delano grape strike nationally and internationally established Chavez's reputation as a labor leader.

After winning their union contracts, the UFW held its first convention in 1971. Vera Cruz was elected the UFW’s second vice-president, becoming the highest-ranking Filipino officer, while Chavez was elected president, and Dolores Huerta was elected first vice-president. At the convention, the UFW also announced the construction of a retirement home, Agbayani Village, for Filipino farmworkers, who had no savings due to poor wages and no families as part of the manong generation, the first generation of Filipinos to immigrate to the US en masse.

The Philippines: A US Territory and the Arrival of the Manong Generation

In 1898, the Spanish American War ended the Spanish colonial rule of the Philippines, and, as part of the Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded the Philippines (as well as Puerto Rico and Guam) to the US for $20 million in compensation. This led to the Philippine American War (1899–1902), as Filipino independence fighters resisted American forces, resulting in the death of 200,000 Filipino civilians and US annexation of the Philippines. Because the Philippines was a US territory, Filipino immigrants could not be excluded, like other Asian immigrants, from entering the US.

The first generation of Filipino immigrants — the manong generation — arrived around 1903 and were primarily young, single men who worked on farms or in factories in California and Hawaii. Due to anti-miscegenation laws — which criminalized interracial marriages and relationships — and immigration restrictions — including the Immigration Act of 1924 — many men of the manong generation were unable to marry or start families and lived their entire lives as single men. Complications further arose after the US recognized the Philippines as an independent country and enacted the Tydings-McDuffie Act. While the act intended to establish the independence of the Philippines over a 10-year transition period, it also restricted Filipino immigration to the US and declared manongs to be aliens rather than nationals. This was then used in an attempt to deport Filipino labor leaders like Mensalvas and Mangaoang. It wasn’t until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which removed national origin quotas, that a new generation of Filipino emigrants could enter and begin families in the US.

Leaving the United Farm Workers Union

In the 1970s, disagreements arose between Vera Cruz and the UFW, namely over the union’s stance on undocumented farmworkers and the Filipino government. The UFW feared growers would use undocumented farmworkers as strikebreakers and would occasionally call immigration authorities on undocumented farmworkers who crossed picket lines. However, Vera Cruz believed the UFW should organize all workers regardless of immigration status. Additionally, Vera Cruz mobilized with Filipino Americans throughout the country to oppose the dictatorship of Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos and call for the end of martial law and political repression in the Philippines. However, in 1977, Chavez accepted Marcos’ invitation to visit the Philippines, where he received a Presidential Appreciation Award. Finding the UFW leadership’s association with Marcos to be antithetical and hypocritical — as a resolution was passed to condemn the Nicaraguan dictatorship at one UFW convention — Vera Cruz resigned from the UFW that year.

Return to the Philippines

In 1987, Vera Cruz returned to the Philippines for the first time in more than 60 years, where he was presented the Ninoy Aquino Award by President Corazon Aquino for his service to Filipino Americans. In 1991, the UCLA Labor Center and UCLA Asian American Studies Center published a book about Vera Cruz, his life, and his role in the history of farmworker labor. In it, Vera Cruz explains that growers would say "that Filipinos made good farmworkers because they were built close to the ground," but notes, "I'm a short Filipino, but it was just as hard for me to bend over as a big white guy."

Return to Activism and the LA Riots

As newer generations began learning about him, Vera Cruz started traveling across the country to speak again about unions and activism. In 1992, Vera Cruz attended the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) founding convention in Washington, DC, where he received an award for being an Asian Pacific American Labor Pioneer. He also joined APALA on the front lines as they marched on the US Department of Justice to protest the acquittal of the police officers accused of beating Rodney King.

Legacy

In 1994, Vera Cruz died at age 89. In 2013, the New Haven Unified School District in the San Francisco Bay Area renamed Alvarado Middle School to Itliong-Vera Cruz Middle School, becoming the first US school to be named after Filipino Americans. Through his organizing, Vera Cruz greatly impacted farming and labor communities in the US.

3.Edward Said (1935–2003): Palestinian American scholar and Palestinian independence activist

Early Life and Education

Dr. Edward Said was born in 1935 in Jerusalem — then part of Mandatory Palestine under British administration — to an Arab Christian family. His father, Wadie Said, a businessman in Jerusalem, joined the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I after emigrating to the US to avoid being drafted by the Ottoman Empire to fight in Bulgaria for the Central Powers. His father’s service earned him and his family US citizenship; however, Wadie Said returned to Jerusalem, where Said attended St. George’s School, a British boys’ school run by Anglican teachers. By 1948, the family moved to Cairo as refugees to avoid the growing conflict over the United Nations partition of Palestine. Said then began attending the Egyptian branch of Victoria College, a British preparatory school that he described as “a school created to educate those ruling-class Arabs and Levantines who were going to take over after the British left.”

Mandatory Palestine and British Betrayal Post-Ottoman Empire

As nationalist movements grew in Europe, Arabs rose up against the Turkish rule of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922) during World War I (1914-1918). Serbians had done so in the early 1800s, Greeks in the 1820s, and Bulgarians in the 1870s, gaining their independence as nascent states. Because the Ottoman Empire sided with the Central Powers (i.e. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria) during the war, the British government encouraged the Arab Revolt — providing financial support and military backing through the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force — and promised to recognize Arab independence post-war through the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence. However, in 1916, the British and French governments agreed to a secret treaty, the Sykes–Picot Agreement, that divided the Ottoman-ruled regions of Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine into British- or French-administered areas. Additionally, the Russian government approved of and received territory through the agreement.

In 1917, the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, announcing their support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” in part hoping to rally Jewish support of the Allied Powers in the West and to protect a critical communication route (through the Suez Canal in Egypt) to British colonies in India via a pro-British Jewish population in Palestine. However, the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence, Sykes–Picot Agreement, and Balfour Declaration contradicted one another. Today, the Balfour Declaration is considered one of the most controversial documents in modern Arab history and a main cause of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It also became a core component of the British Mandate for Palestine that asserted the British government would administer Mandatory Palestine (established in 1920) until it was “able to stand alone.” To that end, Western educational institutions in the Middle East and North Africa — such as the Egyptian branch of Victoria College that Said attended — perpetuated cultural imperialism as they educated students to become anglicized leaders during post-colonialism, as Said himself noted.

In 1947, the Palestine War began, also known as the War of Independence in Israel, during which the Said family left Jerusalem. The war broke out after the United Nations recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine into independent Arab and Jewish states, and saw the clashing of Arab and Jewish communities in Palestine. At the time, Jews made up roughly one-third of the population in Palestine, but because many were European immigrants, Jews owned a total of 7% of the land. However, the partition would have allocated them 56% of the land, upsetting Palestinians. The war resulted in the British government withdrawing from Mandatory Palestine and the establishment of Israel, consequently displacing 700,000 Palestinian Arabs. More broadly, the war became the first Arab-Israeli War of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Life in Academia

Despite Said’s notable academic achievements, Victoria College expelled him in 1951 for poor behavior. As a result, his father sent him to the US, where Said attended the socially elite, college-prep boarding school, Northfield Mount Hermon School, in Massachusetts. In 1957, Said graduated from Princeton University with a bachelor’s degree in English. In 1964, he graduated from Harvard University with a Ph.D in English literature. By 1963, Said joined Columbia University as a member of the English and Comparative Literature faculties. He became a full professor at Columbia in 1970 and ultimately taught there until his death in 2003. In 1998, he noted that his colleagues at Columbia never referred to him as “Arab” or “Palestinian” but “the much easier and vaguer ‘Middle Eastern.’” Throughout his academic career, Said also taught at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and Yale Universities. Though Said never taught university courses on the Middle East, he advocated for Palestinian rights through his numerous works.

The Six-Day War and Its Impact on Said

As far back as the 1970s, Said regularly corresponded with organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Democratic Socialists of America, and the European Coordinating Committee of Non-Governmental Organizations. In 1967, the Six-Day War broke out — also known as the Third Arab-Israeli War — between Israel and a coalition of Arab states. Tensions between them had been high due to a series of back-and-forth military strikes, culminating in Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser closing the Straits of Tiran to Israeli vessels and mobilizing Egyptian military forces in preparation for war. The war itself, which lasted for six days, began after Israel launched a preemptive airstrike against Egyptian and Syrian air forces. In the end, Israel captured Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian territories, as well as the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem. This resulted in further displacement of Palestinian civilian populations as many fled or were forced out of the West Bank. The massive defeat of the Arab armies resulted in demoralization and the decline of secular Arab nationalism, making way for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in the Middle East.

After the Six-Day War, Said began reading more of what was being written about the Middle East and found that the distortions and misrepresentations of the Arab world were systematic — a discovery that caused Said to become politically engaged, expanding from literary critic to cultural critic. “Until 1967, I really didn’t think about myself as anything other than a person going about his work,” Said described. “I had taken in a few things along the way. I was obsessed with the fact that many of my cultural heroes — Edmund Wilson, Isaiah Berlin, Reinhold Niebuhr — were fanatical Zionists. Not just pro-Israeli: They said the most awful things about the Arabs, in print. But all I could do was note it. Politically, there was no place for me to go. I was in New York when the Six-Day War broke out; and was completely shattered. The world as I had understood it ended at that moment. I had been in the States for years, but it was only now that I began to be in touch with other Arabs. By 1970, I was completely immersed in politics and the Palestinian resistance movement.”

Orientalism and Postcolonial Theory

In 1978, Said published Orientalism, in which he examined how Western scholarly and literary depictions of “the Orient” — particularly, the Arab Islamic world — reinforce Western imperialism. Said argued that these Western depictions project a stereotypical “otherness” on the Orient, thereby perpetuating a negative perception of the Eastern world and facilitating Western colonial policy. Orientalism became not only Said’s best-known work but also one of the most influential scholarly works of the late 20th century. Furthermore, it became foundational to the field of postcolonial studies, and Said became known as an originator of postcolonial theory and discourse. While other figures – including Noam Chomsky, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, and Simone Weil – had made similar arguments regarding imperialist narratives, Said synthesized multiple disciplinary fields — including literary theory, cultural studies, and anthropology — lending to the intellectual impact of Orientalism.

Palestinian Independence and Two- vs. One-State Solutions

From 1977 to 1991, Said was an independent member of the Palestinian National Council (PNC). 1988, he advocated for the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and voted to establish the State of Palestine at the PNC meeting in Algiers. The two-state solution proposes establishing two states to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Israel for Jews, and Palestine for Palestinians. In his beliefs, Said was critical of the West and Israel, drawing parallels between Zionism and European imperialism. However, he also saw both Jews and Palestinians as victims — more specifically, he described Palestinians as the “indirect casualties of unprecedented European crimes against Jews.” His nuanced stance caused many American supporters of Israel to view him as a radical (if not an anti-Semite or terrorist), while many Palestinians found him to be moderate, with some even criticizing his acknowledgment of Jewish suffering as too Americanized.

Though he supported the two-state solution, Said quit the PNC in 1993 in protest of the internal politics that led to the signing of the Oslo Accords by Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leader Yasser Arafat. The Oslo Accords were intended to be a peace process between the PLO and Israel that would grant the right of Palestinians to self-determination. However, Said condemned them as “an instrument of Palestinian surrender” that did not result in an independent State of Palestine but rather inadvertently consented to new, semi-permanent occupation methods. He continued to criticize the deal after its signing, resulting in the Palestinian Authority banning his books in Palestine. The subsequent effects of the Oslo Accord and later Wye River Memorandum — also known as Oslo II, which meant to restore old Israeli and Palestinian promises and return two-fifths of the West Bank under Palestinian control — led Said to embrace the one-state solution in 1999, calling for a binational Israeli-Palestinian state wherein all members are citizens with the same privileges and resources.

Legacy

In 2003, Said died at the age of 67 due to leukemia. In 2009, Columbia University Libraries acquired his papers and books, housing them in a special reading room. Regardless of the support or criticism they received, Said’s work is still taught in US universities, and he is considered to be one of the most prominent Palestinian independence advocates in the US.

4.Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943–2000): Japanese American civil rights, anti-war, gay liberation, and AIDS activist

Early Life and Student Activism

Third-generation Japanese American activist Kiyoshi Kuromiya was born in 1943 in a Japanese incarceration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. In 1945, his family was released from the camp and returned to California. In 1961, Kuromiya moved to Philadelphia to attend the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied architecture and began his activism by participating in demonstrations and sit-ins. As a gay man, Kuromiya's activism was in part inspired by how closeted he found the University of Pennsylvania to be.

Civil Rights, the March on Washington, and the Selma March

In 1963, Kuromiya participated in the March on Washington and attended Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, where he later met and befriended King. During the Selma to Montgomery marches, Kuromiya was beaten unconscious by Alabama state police while leading a group of high school students to the state capitol building. He was hospitalized and received 20 stitches in his head. Throughout the civil rights movement, Kuromiya and King became so close that Kuromiya helped look after King's children during the week of his funeral after King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. On April 11, Kuromiya was arrested by the FBI for "obscene, indecent, and crime-inciting work."

Protesting the Vietnam War: "Fuck the Draft" and the Fake Americong

Earlier, Kuromiya had created the iconic "Fuck the Draft" poster in protest of the Vietnam War. The poster featured a young white man, activist Bill Greenshields, burning his draft card with the phrase "Fuck the Draft" in large, capital letters underneath. Kuromiya used the pseudonym Dirty Linen Corporation and advertised the posters as "the perfect gift for Mother's Day," saying, "Buy five, and we'll send a sixth one to the mother of your choice." Despite his arrest, Kuromiya went on to disseminate 2,000 copies of the poster at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in August of that year.

After his arrest, Kuromiya returned to the University of Pennsylvania and spread a story that the Americong — a fake group — planned to burn a dog with napalm (an incendiary mixture used heavily in the Korean and Vietnam Wars) in protest of the Vietnam War on April 26, 1968. That day, thousands appeared on campus to prevent the burning; however, they were instead handed leaflets created by Kuromiya that read, "Congratulations, you've saved the life of an innocent dog. How about the hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese that have been burned alive? What are you going to do about it?"

Gay Rights After Stonewall

Following the Stonewall riots in 1969, Kuromiya co-founded the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). The GLF stood in solidarity with the Young Lords Party (a Puerto Rican street gang-turned-civil rights group) and the Black Panther Party, with Kuromiya serving as an openly gay delegate to the Black Panther Convention. While Kuromiya came out to his family around the age of 8-9, he officially came out in 1965 at the first (of five) Annual Reminder protest, which called for basic civil rights and protections for LGBTQ people.

AIDS Advocacy, Diagnosis, and Creating One of the Internet's First Websites

In the early 1980s, Kuromiya began advocating for the AIDS movement in the US and was diagnosed with AIDS himself in 1989. He founded the Philadelphia chapter of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and created the ACT UP Standards of Care. Kuromiya believed that "information is power" and educated himself on AIDS issues, eventually being invited to participate in the National Institutes of Health alternative therapy panels.

Kuromiya also founded the Critical Path newsletter, one of the first publicly available HIV treatment resources, and mailed it to people around the world, including incarcerated individuals. To overcome the limitations of physical mail, Kuromiya turned the Critical Path newsletter into one of the first websites on the Internet. He further developed the site into the Critical Path AIDS Project, which included establishing a 24-hour hotline and providing free internet to people with HIV in Philadelphia through a network of computers he built in his apartment.

The Supreme Court and Marijuana Legalization

Due to the sexually explicit information regarding AIDS on the internet, Kuromiya joined the ACLU in 1997 in the Supreme Court case Reno v. ACLU to strike down the Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1996. The CDA, signed into law by President Clinton, aimed to protect minors from "obscene or indecent" material on the internet, which included offensive "sexual or excretory activities or organs." However, as the Supreme Court found, the act came down to a blanket restriction of free speech as it failed to define "indecent" communications. In 1999, Kuromiya also filed a suit for the legalization of marijuana for medical use for people with AIDS, though the court dismissed his claims.

Legacy

In 2000, Kuromiya died at the age of 57. However, his work and impact continue to live on across numerous communities and generations to come.

5.Haunani-Kay Trask (1949–2021): Native Hawaiian rights and Indigenous rights activist, scholar, author, and poet

Early Life and Lineage

Born in 1949, Dr. Haunani-Kay Trask grew up in Hawaii on the island of O’ahu. Describing her lineage, Trask wrote, “When I meet another Hawaiian, I say I am descended of two genealogical lines: the Pi'ilani line through my mother, who is from Hana, Maui, and the Kahakumakaliua line through my father’s family from Kauai.”

Education and Intersectionality on the Mainland

She attended Kamehameha Schools — a Hawaiian private school system established by the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate under the will of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop (1831–1884), who wanted to see her people flourish through education after experiencing their decline. (An analysis estimates there were 683,000 Native Hawaiians in Hawaii when British explorer James Cook arrived in 1778. By 1840, the Native Hawaiian population declined 84%.)

Trask earned her bachelor’s degree in 1972, master’s degree in 1975, and Ph.D. in 1981 in political science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. During her studies on the mainland, Trask developed an intersectional understanding of racism, capitalism, Indigenous beliefs, and transnational feminism. She also became a supporter of the Black Panther Party and anti-war movements, protesting the Vietnam War.

Academic Career and the Founding of Hawaiian Studies

In 1981, Trask began her academic career at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa as an assistant professor in the American studies department with expertise in feminist theory and Indigenous studies. She was the first Indigenous woman hired as a lecturer at UH Mānoa and is credited with co-founding the field of Hawaiian Studies, later becoming the founding director of the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at UH Mānoa — a position she maintained until retiring in 2010.

The establishment of Hawaiian Studies resulted in part from the growing Hawaiian sovereignty movement and Aloha ʻĀina, which progressed alongside the civil rights movement, global decolonization struggles, and anti-imperialism movements, and the American Indian Movement. To further educate people on cultural and political Hawaiian issues, Trask began hosting and producing a monthly public-access TV series, First Friday, in 1986.

Grassroots Organizing and Anti-Tourism

Trask was also a founding member of Ka Lahui Hawaii, a grassroots initiative that advocates for Hawaiian sovereignty and self-determination for Native Hawaiians, which held its first convention and adopted its constitution in 1987. Ka Lahui Hawaii in part defined sovereignty with the following elements: a common culture (including language), a land base, a government structure, an economic base, and self-sufficiency.

Likewise, Trask opposed tourism in Hawaii, writing, “In Hawai'i, the destruction of our land and the prostitution of our culture is planned and executed by multi-national corporations, by huge landowners, and by collaborationist state and county governments.” For context, the 2021 US Census estimates that Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders make up 10% of the population in Hawaii; however, they make up 51% of people facing homelessness in Hawaii.

Oppression and Endangerment of Hawaiian Culture

A critical aspect of any culture, language was championed by Ka Lahui Hawaii in their mission for Hawaiian sovereignty, in particular, because the Hawaiian language nearly died out. In 1896 — three years after the overthrowing of the Hawaiian monarchy — the provisional government declared English the official language used in education. This “English-only” law was modeled on broader assimilation policies to eradicate the indigenous languages of Native Americans. Though Hawaiian was not outright banned, it was effectively forbidden from being spoken in schools, as teachers punished children speaking Hawaiian on school grounds and even reprimanded parents for speaking Hawaiian at home. By the 1970s, reports estimate only 1,000-2,000 Native Hawaiian speakers remained, most of whom were part of older generations.

During the 1978 Constitutional Convention, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs was created, and the State Constitution was amended to mandate that the State promote “the study of Hawaiian culture, history, and language’ and recognize Hawaiian as an official language. This political progress contributed to the eventual founding of the field of Hawaiian Studies by establishing educational courses around Hawaiian culture, history, and language. Today, Olelo Hawai’i, the Native Hawaiian language, is still considered an endangered language, as also listed by the United Nations.

Making National Headlines As a “Racist” and Hawaiian Nationalism

In 1990, Trask made national headlines when Joseph Carter, a white student majoring in philosophy at the University of Hawaii, wrote a letter to the student newspaper about “Caucasian bashing” and argued that “racism is not an exclusively white endeavor.” To exemplify his point, Carter claimed that the Hawaiian word “haole” — which means “foreigner” but is often associated with white people — was a pejorative for Caucasians. Trask responded through her own letter to the newspaper in which she explained the white oppression of Native Hawaiians and asserted that “Mr. Carter does not understand racism at all” and should leave the state. In addressing the use of “haole,” Trask stated, “Only new arrivals resent it because they have not had experience in a numerical minority.” At the time, the island’s racial population was 33.4% white, 12.5% Native Hawaiian, and nearly 50% Asian.

After Trask’s response, Carter did, in fact, return to Louisiana (though he later returned and re-enrolled), and critics began calling Trask “a racist who abused her position by lashing out at a student.” The philosophy department even condemned Trask in a unanimously approved resolution calling for her removal. However, the Center of Hawaiian Studies denounced the philosophy department’s use of “plantation tactics of threat, reprisal, and intimidation.” As reported by the New York Times, people of various ethnic backgrounds deemed Trask’s vehemently raising these issues “un-Hawaiian,” claiming that the Hawaiian way “is to be gentle, patient, and circumspect.” To this criticism, Trask declared, “I am not soft. I am not sweet, and I do not want any more tourists in Hawaii.”

She later defended her stance that same year on an episode of “Island Issues” and responded to callers who took issues with her views, including referring to Hawaii as “stolen land.” In one response, Trask compared the forcible colonization of Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, Alaska, Native lands, Guam, Micronesia, and Pulau by the US to the taking of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union, declaring Americans the recipients of imperialist traditions.

Protests for Hawaiian Sovereignty and Notable Works

On January 17, 1993, the Centennial of the Overthrow — the 100-year anniversary of the overthrowing of the Hawaiian monarchy — Trask led a march of 15,000 Native Hawaiians and famously delivered a speech on the steps of Iolani Palace about Hawaiian sovereignty, one of the first major protests calling for the return of native lands in Hawaii. Hawai’i Public Television also broadcasted the award-winning documentary, “Act of War: The Overthrow of the Hawaiian Nation,” co-written and co-produced by Trask, during the centennial.

A few months later, Trask published her most notable book, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i, a “well-reasoned attack against rampant abuse of Native Hawaiian rights, institutional racism, and gender discrimination.” In the book, Trask also discusses Ka Lahui Hawai'i’s plan for Hawaiian self-government and the 1989 Hawai'i declaration of the Hawai'i Ecumenical Coalition on Tourism. Accordingly, From a Native Daughter is considered a foundational text in indigenous rights.

Indigenous Rights

Beyond her work in Hawai’i, Trask advocated for indigenous rights and represented Native Hawaiians at the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples in Geneva, as well as in Samiland (Norway), Aotearoa (New Zealand), Basque Country (Spain), and Indian nations throughout the United States and Canada. She also participated in the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance in Durban, South Africa in 2001.

In 2004, she opposed the Akaka Bill — which proposed a process for US federal recognition for Native Hawaiians similar to Native American tribes — because it prohibited Native Hawaiians from receiving benefits available to federally recognized Indian tribes.

Legacy

In 2021, Trask died due to cancer at age 71. Nevertheless, Trask's fight to champion Hawaiian sovereignty and educate new generations as a scholar, poet, and activist directly lives on through the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at UH Mānoa.

6.George Helm (1950–disappeared 1977): Native Hawaiian rights activist and musician

Early Life, Music, and Activism

Native Hawaiian activist George Helm Jr. was born in 1950 in Hawaii on the island of Moloka’i. At age 15, he moved to O'ahu to play basketball for St. Louis School, where he also studied music under “Living Treasures of Hawaii” John Keola Lake and Kahauanu Lake. After graduating in 1968, Helm began working as a traveling musician for Hawaiian Airlines and became known as one of the greatest Hawaiian falsetto vocalists of all time. However, he was disillusioned by the “plastic” feel of attracting tourists to the islands, according to his older sister, Stacy Helm Crivello. Aware of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and land issues, Helm began to focus on front-line activism and Aloha ʻĀina.

In 1975, Helm co-founded Hui Alaloa, a Moloka’i-based group that organized marches to reclaim Hawaiian access to natural resources and land, including beaches and forests, that were being closed off or developed by large landowners and foreign investors. As a result, landowners opened roads to beaches around the island. This success sparked a new political consciousness around Hawaiian activism and rights across the state as antimilitary sentiment also grew.

Antimilitary Sentiment, Martial Law, and the Bombing of a Hawaiian Island for US Military Training

A major cause of the growing antimilitary sentiment was the continued use of Hawaiian islands — in particular, Kaho’olawe — for military training and bombing ranges. Despite being forcibly annexed in 1898 after the US government overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, Hawaii did not become a state until 1959. In 1910, the then-Territory of Hawaii designated Kaho’olawe as a forest reserve in an effort to restore the island after being used as a penal colony and for ranching (which destroyed its vegetation) for nearly a century. However, the program failed, and Angus MacPhee, a Wyoming rancher, leased the island in 1918 to build a cattle ranch. Due to regular droughts, MacPhee sublet the island to the US Army, which began using it as military training grounds.

When the US declared martial law in Hawaii after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Kaho’olawe was used as a bombing range to simulate war in the Pacific Islands. Training and bombings on Kaho’olawe continued well after World War II, including during the Cold War (1947-1991), Korean War (1950-1953), and Vietnam War (1954-1975). In 1965, the Navy conducted Operation Sailor's Hat to simulate nuclear blasts, determine their effects, and test the blast resistance of Navy ships. Each of the three explosive tests involved detonating 500 tons of conventional TNT on Kaho’olawe to target ships stationed off the island’s coast. While the ships survived, the blasts left a crater on the island that became known as “Sailor Man’s Cap.” It’s also speculated that the blasts cracked the island’s caprock, causing freshwater to be released into the ocean.

Protesting the Government and Occupying Kaho’olawe

In 1976, to protect the environment and cultural resources of Kaho’olawe, Helm and a group of activists formed the Protect Kaho’olawe ‘Ohana (PKO) and filed a suit to stop the Navy from using Kaho’olawe as training and bombing sites. Helm served as PKO’s president and researched federal laws regarding everything from marine protections and endangered species to indigenous rights to identify any statutes the Navy had violated. On January 6, 1976, in an attempt to halt the bombings, Helm gathered with a group of more than 50 people on Maui to “invade” Kaho’olawe — located seven miles southwest of Maui — and occupy the island. En route to Kaho’olawe, a Coast Guard helicopter intercepted the group and warned that any boats approaching the island would be trespassing and therefore confiscated. Of the 10 boats, one boat — carrying nine people — continued on and made it to the island. They became known as the Kaho’olawe Nine and included Helm, Walter Ritte Jr., and Kimo Mitchell. This inspired a series of occupations, and the Kaho’olawe Nine organized and helped ferry protesters to and from the island.

Mysterious Disappearance

On January 30, 1977, Mitchell and his friend, Sluggo Hahn, brought five men to Kaho’olawe, including Helm, Ritte, and Richard Sawyer. Ritte and Sawyer stayed on the island to prevent the Navy from bombing it, while the other three returned and attempted to secure federal action. However, the Navy resumed bombing on February 10. On February 12, Helm addressed the State House of Representatives and urged them to consider Ritte’s and Sawyer’s lives, which were endangered by not only bombs but “the negligence of politicians.” As concern grew for Ritte’s and Sawyer’s safety, Helm organized a large occupation attempt on February 20, but it was derailed by the Coast Guard. Only 10 of what initially began as more than 100 people landed on Kaho’owale, but none were able to make contact with Ritte and Sawyer.

On March 5, Helm, Mitchell, and Billy Mitchell (unrelated) set out to Kaho’olawe to find Ritte and Sawyer. Unbeknownst to them, the military would locate the two men that same day. The three originally planned to find Ritte and Sawyer, then wait to be picked up by Hahn’s boat. According to Billy Mitchell, unable to locate Ritte and Sawyer (as they’d already been found), the three waited at their pickup point for Hahn’s boat. However, Hahn’s boat had sunk at its dock in Maui. As it never arrived, the three decided to paddle the seven miles back to Maui using two surfboards they’d cached on the island. Due to rough waters, Billy Mitchell ultimately returned to Kaho’olawe alone to seek help from military installations. He last saw Helm and Kimo Mitchell near Molokini, a submerged volcanic crater that forms an uninhabited islet roughly two miles off the coast of Maui.

PKO’s Continued Advocacy and Impact

PKO members, family, and the Navy searched for Helm and Mitchell, but they were never found. Helm was 26, and Mitchell was 25. Though devastated by their mysterious disappearance, PKO continued its movement. Later that year, the court came to a decision regarding PKO’s earlier civil suit and ruled that the Navy could continue to use the Kaho’olawe but must prepare an environmental impact statement and inventory of historic sites on the island. In 1978, John Waihe’e, an attorney from PKO’s civil suit, helped introduce and pass the Hawaiian Affairs Package which included reform proposals, recognition of Native Hawaiians’ rights to land and natural resources, and a mandate that the state must promote Hawaiian studies in public schools. It also led to the creation of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Carrying Helm’s legacy, PKO impacted economic development, environmental rights, and education in Hawaii and contributed greatly to Native Hawaiian leadership. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush ordered the Secretary of Defense to stop the bombing of Kaho’olawe. In 1993, Congress voted to end military use of Kaho’olawe, transfer the island back to the state, and authorize $400 million for ordnance removal. The Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission was formed the next year. In 2004, the Navy ended its clearance project, having cleared 75% of the island’s surface of unexploded ordnance. Despite the danger, volunteers continue to visit the island to help clear the remaining 25% and restore the island. State law now dictates that Kaho’olawe can only be used for Native Hawaiian cultural, subsistence, and spiritual purposes, fishing, environmental restoration, historic preservation, and education. It also prohibits commercial use.

Legacy

Having pioneered many Hawaiian sovereignty concepts and philosophies, Helm is recognized as one of the Aloha ʻĀina movement’s greatest activists, and his music continues to play regularly throughout Hawaii.

7.Rushan Abbas (1967–Present): Uyghur American human rights activist

Early Life and Student Activism

Uyghur American activist Rushan Abbas was born in Ürümqi — the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in northwestern China — in 1967. Prior to being formally annexed by the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912; succeeded by the Republic of China) as Xinjiang (“new territory”) in 1884, the region was known as East Turkistan. From 1984 to 1988, Abbas majored in biology at Xinjiang University, where she organized pro-democracy rallies and demonstrations to protest against China’s policies in the XUAR. Pre-dating the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, these protests included resisting discriminatory education and birth control policies, nuclear testing in the Lop Nur region, the lack of the region’s true autonomy and representation in government, and employment opportunities.

Immigrating to and Advocating in the US

After graduating from university, Abbas was unable to find employment due to government retaliation against her activism. In 1989, concerned for her safety, Abbas’ father, Borhan Abbas — a Uyghur scholar, academic author, and public figure — urged her to leave for the US, where she pursued a master’s degree at Washington State University. She became a US citizen and continued advocating for the human rights of Uyghurs in the XUAR. A Turkic ethnic group, Uyghurs mostly live in the XUAR and are therefore recognized as an ethnic minority in China.

In 1993, Abbas co-founded and served as vice president of the California-based Uyghur Overseas Student and Scholars Association, which served as the blueprint for the eventual establishment of the Uyghur American Association (UAA) in 1998. In retaliation, China punished her father by forcibly retiring him at 59, removing him from his position as the chairman of the Science and Technology Council of the XUAR. Abbas subsequently served as the vice president of UAA for two terms. Later in 1998, Radio Free Asia — an American nonprofit that broadcasts radio programs and publishes news online to provide uncensored, accurate reporting to audiences in Asia — launched its Uyghur service, and Abbas became the first Uyghur reporter to broadcast daily to the Uyghur region.

Uyghur Detainees in Guantánamo Bay and China’s “War on Terror”

In 2002, a few months after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Abbas served as a translator for 22 Uyghur men who were being transferred to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, from Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan. Of the 22 men, five had been captured by American forces in Afghanistan while 17 were captured by police in Pakistan. Despite there being no evidence or history of these men harboring anti-American sentiment, the US held some of them in the Guantánamo Bay detention center for 12 years. However, there had been tension in the XUAR between Uyghurs — who are predominantly Muslim — and the Chinese government dating back to the 1930s (though East Turkistan separatist movements pre-date 1930). By 2002, there had been numerous Uyghur attacks against Han Chinese in the XUAR — attributed to growing Uyghur frustration with the increasingly repressive political climate, restricted religious freedom, and China’s 1996 “Strike Hard” campaign against crime, which saw the arrest and execution of thousands of Uyghurs.

Though the Chinese government had treated conflict in the XUAR as a local issue, it began depicting Uyghur dissent as “al-Qaeda-style terrorism” after 9/11, consequently portraying its Uyghur repression as counterterrorism. It also designated the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a Muslim separatist group founded by militant Uyghurs, as a terrorist organization — a designation the US had initially resisted only to adopt after 9/11. The Chinese government accused the 22 detained Uyghur men of being members of ETIM; however, without any evidence connecting them to ETIM, the US determined they were “non-combatants” and eligible for release. Due to difficulties finding a safe country to accept them, the final three men were not released until 2013. Six months into translating, Abbas realized the interrogations were useless. However, she continued to translate until 2013, working with the US Department of Defense, Department of Justice, State Department, and US administration to help release and then resettle the men.

Beijing Hosts the Olympics

In 2008, protesters demonstrated around the world during the Olympic Torch Relay for the Summer Olympic Games in Beijing — including in London and Paris, where they forced officials to repeatedly extinguish the torch — against China’s violent crackdown on anti-Beijing protests in Tibet and record of human rights violations. Abbas took part in the protests in San Francisco, where city officials shortened and rerouted the relay to avoid protesters. She’s also spoken out about the International Olympic Committee’s decision to allow Beijing to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

Campaign for Uyghurs and the Uyghur Genocide

In 2017, Abbas founded the Campaign for Uyghurs, a nonprofit that advocates for human rights and democratic freedom for Uyghurs, as well as mobilizes the international community to stop human rights violations in East Turkistan (XUAR). With Abbas as executive director, the nonprofit often engages in activism at a federal level to pass legislation in the US that restricts forced labor and advances human rights. In March 2018, Abbas led the “One Voice One Step” initiative, a group of Uyghur women who successfully organized a simultaneous demonstration in 14 countries and 18 cities to protest China’s detention of Uyghurs in concentration camps.

Since 2017, the Chinese government has detained between 1 to 2 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in the XUAR (including Kazakh and Kyrgyz) in camps under the guise of re-education and antiterrorism. According to human rights groups, the detainees are forced to “study Marxism, renounce their religion, work in factories, and face abuse.” Moreover, the Chinese government has targeted more than 5,500 Uyghurs outside of China via cyberattacks and threats against relatives in China, while detaining and/or forcing more than 1,500 Uyghurs to return to China for imprisonment. Beyond detainment, Uyghurs in the XUAR are subjected to mass surveillance, forced sterilization, and torture. Though the Chinese government denies committing human rights violations in the XUAR, human rights groups and several countries, including the US, have declared its actions a genocide and crimes against humanity.

China Retaliates by Detaining Her Family

In September 2018, Abbas participated in the Hudson Institute’s panel, “China’s ‘War on Terrorism’ and the Xinjiang Emergency,” where she spoke about how the mass internment of Uyghurs in concentration camps under the guise of China’s “War on Terror” constituted genocide. She also described the mental and physical abuse of Uyghur women, including forced unknown injections, sterilizations, and (gang) rape. Six days later, both Abbas’ sister, Dr. Gulshan Abbas, who lived in Ürümqi and worked at a government-run hospital, and her aunt disappeared. For years, Abbas and her family suspected the Chinese government had taken them into custody, but it wasn’t until 2020 that the Chinese government confirmed Dr. Gulshan Abbas had been sentenced to 20 years in a prison camp for alleged terrorist activities. Days later, Dr. Gulshan Abbas’ daughter informed the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) of her mother’s sentence, and the US called for her release.

Continued Advocacy and Nobel Peace Prize Nomination

Continuing her advocacy, Abbas testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the XUAR concentration camps in 2019. She also testified before the House of Representatives on international religious persecution and the role of Islamophobia in China’s human rights violations in 2020, and on forced labor in the XUAR in 2021. In 2020, she published “Genocide in East Turkistan,” a report in which she outlined how the actions of China’s government met every condition of genocide as defined by the Genocide Convention, an international treaty adopted by the United Nations in 1948 in response to the Holocaust.

In 2021, the US concluded that China has committed “genocide and crimes against humanity” against Uyghurs. In 2022, US legislators nominated the Campaign for Uyghurs and Uyghur Human Rights Project for the Nobel Peace Prize, citing their “significant contributions to building fraternity between nations and promoting peace by defending the human rights of the Uyghur, Kazakh, and other predominately Muslim ethnic minorities that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has targeted with genocide and other crimes against humanity.”

Legacy

Today, Abbas persists in her fight for Uyghur human rights and freedom, both in the US and internationally, and the release of her sister, Dr. Gulshan Abbas.

8.Manjusha Kulkarni (1969–Present): Indian American human and civil rights activist and attorney

Early Life, Immigrating to the US, and Early Experiences of Racial Discrimination

Born in 1969, Manjusha Kulkarni immigrated to the US from India as a child in 1971 as part of the post-1965 immigration wave. Because her parents were both physicians, they were able to acquire professional visas, and the family moved to Alabama. When she was 10, Kulkarni witnessed a Birmingham hospital deny her mother a position due to her immigrant status. “At her review,” Kulkarni described, “the panel of white male physicians asked very bluntly, ‘Why are you foreigners coming to the United States and stealing our jobs?’”

However, her mother’s experience was not an isolated incident, as the hospital had routinely been denying foreign graduates from joining its residency program. Consequently, Kulkarni’s parents filed a class-action lawsuit against the hospital, causing it to reform its residency program. Kulkarni credits that experience with showing her how the law could be used as a “vehicle for change” and to “redress wrongs,” motivating her to pursue a political science degree from Duke University and a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law.

Growing up South Asian in the US also informed Kulkarni’s understanding of race and politics. One formative incident includes her AP American History teacher using her and another South Asian student to justify the use of internment camps. “The teacher asked everyone whether I should be interned, along with another South Asian student in the class, if we were to go to war with India. Every single person in the class, except my best friend who was African American, voted to intern us. … It was illuminating for me, especially given that she was my favorite teacher, of sort of how people view race in America, and specifically at that time South Asian Americans, I think, too, in terms of that xenophobia and perpetual foreignness that a lot of us have,” Kulkarni shared.

Pursuing a Civil Rights Career Through Law and Advocacy

After graduating with her bachelor's degree, Kulkarni took a gap year and worked at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) — where she conducted “research to challenge district-wide voting to dilute the Black vote in Alabama” — and the Attorney General’s Office in Montgomery, Alabama. Driven to pursue a civil rights career, Kulkarni, while in law school, clerked at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) — where she “sought redress for Japanese Latin Americans abducted by the US government during WWII” — the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) — where she helped “craft legal arguments to secure in-state tuition for undocumented students” — and the US Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles, California.

In 1999, Kulkarni began working as an attorney at the National Health Law Program (NHeLP) to make quality healthcare more accessible for low-income individuals, people of color, people with disabilities, children, and the elderly. In 2010, she left NHeLP for South Asian Network (SAN), a support services nonprofit, where she served as Executive Director. SAN aims to empower South Asian Americans, increase resource access, and raise civic engagement and advocacy among community members, including in areas of health equity and gender-based violence. In 2014, the Obama administration awarded Kulkarni the White House Champions of Change award for her work educating Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders about the Affordable Care Act through her work at NHeLP and SAN.

Joining AAPI Equity Alliance and Co-founding Stop AAPI Hate Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

After SAN, Kulkarni joined AAPI Equity Alliance — formerly known as the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council (AP3CON) — as Executive Director. Founded in 1976 as APPCON, AAPI Equity Alliance is a coalition of more than 40 community-based organizations that serve and represent the 1.5 million Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Los Angeles, California. It focuses on issues from political advocacy to social justice. In 2020, Kulkarni cofounded Stop AAPI Hate with Cynthia Choi and Russell Jeung, launched by AAPI Equity Alliance, Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA), and San Francisco State University’s Asian American Studies Department. Created in response to the spike in xenophobia and hate crimes from the COVID-19 pandemic, Stop AAPI Hate tracks and responds to incidents of hate crimes and discrimination against Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. The coalition also uses its data to advocate for policies that strengthen human and civil rights protections and dismantle systemic racism against communities of color.

Between March 2020 and December 2021, Stop AAPI Hate recorded a total of 10,905 hate incidents against Asian and Pacific Islander Americans — 42.5% of which occurred in 2020 and 57.5% in 2021. These incidents comprised 63% of verbal harassment, 16.2% of physical assault, 16.1% of deliberate avoidance, 11.5% of civil rights violations (including workplace discrimination, being barred from transportation, etc.), and 8.6% of online harassment. Hate incidents reported by women made up 61.8% of all reports. California, New York, Washington, and Texas made up the top states with the largest number of hate incident reports. To take action addressing these incidents, Stop AAPI Hate works with policymakers to provide solutions, such as the California State Policy Recommendations to Address AAPI Hate.

Condemning the Trump Administration and Tracing Anti-Asian Sentiment Throughout US History

In 2020, Kulkarni — with Stop AAPI Hate co-founders Choi and Jeung — wrote an op-ed article for the LA Times condemning President Trump’s racist comments — he began calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” in March 2020 — for framing how Americans view Chinese people and therefore fueling hate crimes against Asian Americans. Kulkarni’s article cites Asian Americans being coughed on, spat on, and stabbed by perpetrators blaming them for the pandemic. In the article, Kulkarni, Choi, and Jeung liken these hate incidents to the 1982 murder of 27-year-old Chinese American Vincent Chin by two white men — Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens and his stepson, autoworker Michael Nitz — who believed he was Japanese and therefore “responsible for the decline of the American auto industry” and recent layoffs. Resentful of Japan’s success in the auto industry — a common anti-sentiment at the time — Ebens and Nitz beat Chin to death with a baseball bat in Detroit on the night of his bachelor party.

Before he lost consciousness, Chin whispered his last words to his friends, “It’s not fair.” Despite being convicted of manslaughter (brought down from second-degree murder in a plea deal), Ebens and Nitz were sentenced to pay $3,000 and no jail time, sparking outcry in Asian American communities. Kulkarni, Choi, and Jeung further connect the anti-Asian sentiment and scapegoating during the COVID-19 pandemic to the segregation of 30,000 Chinese Americans in San Francisco during the bubonic plague, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and the surge in Islamophobic hate crimes against Muslims in the US after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 (which also largely targeted Sikhs who were thought to be Muslim).

Legacy

In 2021, Kulkarni, Choi, and Jeung made Time’s 100 Most Influential People of 2021 for Stop AAPI Hate, which has become “an invaluable resource for the public to understand the realities of anti-Asian racism” and “a major platform for finding community-based solutions to combat hate.” As an integral activist, Kulkarni continues to advocate for, empower, and affect positive change for Asian and Pacific Islander American communities.

Support AAPI-centered content by exploring how BuzzFeed is celebrating Asian Pacific American Heritage Month! Of course, the content doesn't end after May. Go follow @buzzfeedapop to keep up with our latest AAPI content year-round!

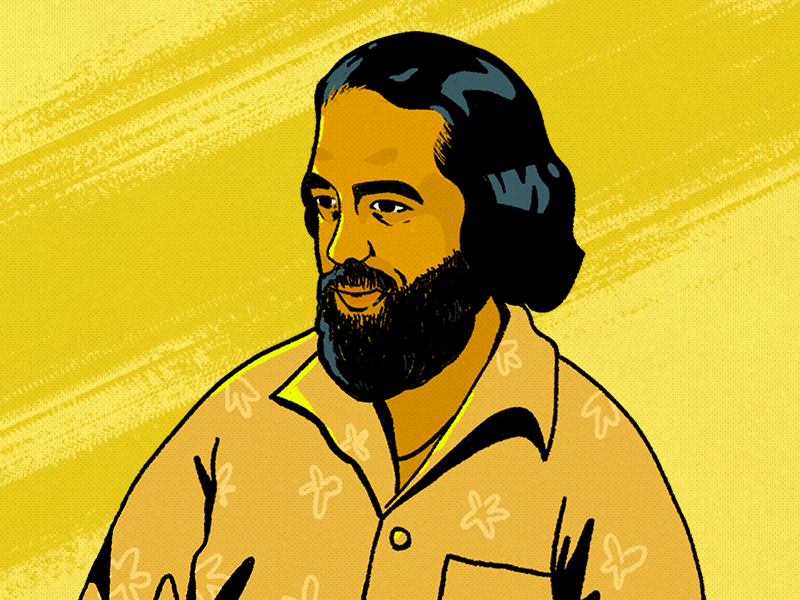

From Left to Right: Haunani-Kay Trask, Rushan Abbas, Manjusha Kulkarni, Kiyoshi Kuromiya, Philip Vera Cruz, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, George Helm, and Edward Said