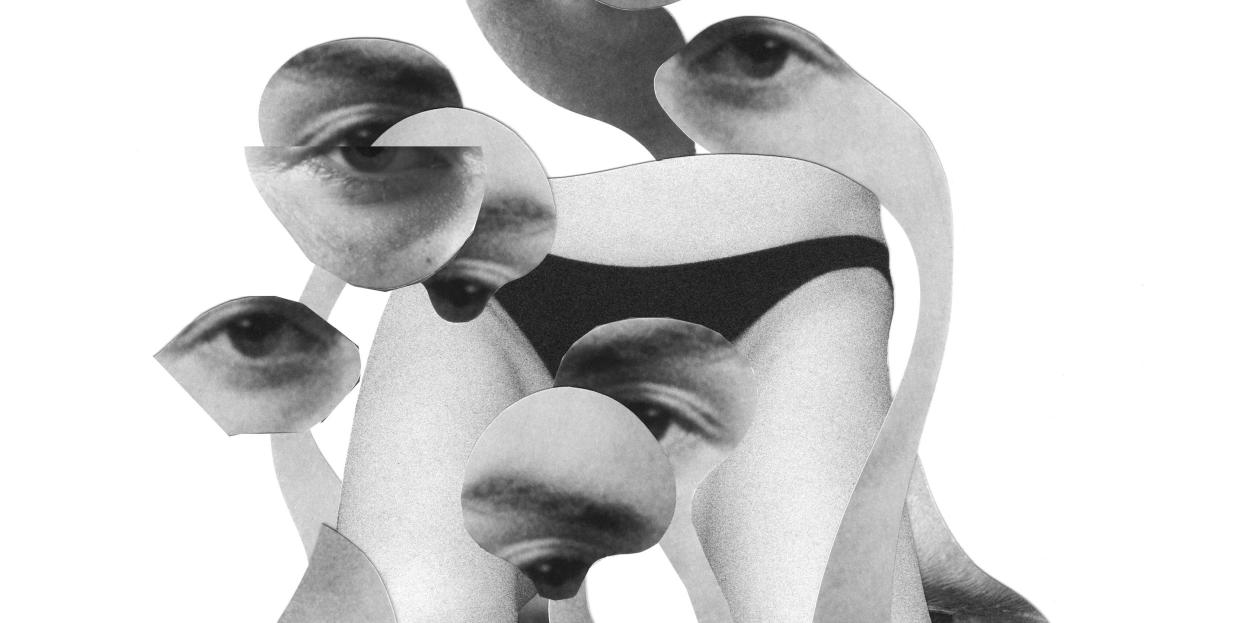

Medical Students Regularly Practice Pelvic Exams on Unconscious Patients. Should They?

In 2016, Katie* had just started her first clinical rotation for the Yale School of Medicine. For six weeks, she would work in Bridgeport Hospital’s ob-gyn department, during which time she’d be shepherded in and out of operating rooms by residents and attending physicians. Katie, then 28, rarely met patients before their surgeries. Instead, the third-year student would often show up at an operating room, where the female patient was already unconscious, and observe or perform whatever maneuver her superiors requested. (She remembers once asking if she could pre-round on patients before surgery in order to introduce herself. She was told no.)

Katie once performed a pelvic exam on a woman who was under anesthesia. This involves placing two fingers into the vagina while a second hand is placed on the patient’s abdomen to feel for ovaries, masses, and uterine mobility. Pelvic exams, a regular part of gynecological visits, are necessary before gynecological surgery, as they allow physicians to examine anatomy before performing procedures like hysterectomies and fibroid removals. At teaching hospitals, where medical students are involved in patient care, students regularly perform these exams for educational training. They’re often the third or fourth person to conduct the procedure, after an attending physician and one or two residents. Katie had not met the female patient before she inserted her fingers into her vagina. She didn’t know if the patient even knew she was in the room. “I’m certain [she] did not give consent,” Katie says now, three years later. “I would be shocked if the [resident or attending] got it on my behalf.”

This spring, ELLE conducted a survey of 101 medical students from seven major American medical schools. Ninety-two percent reported performing a pelvic exam on an anesthetized female patient. Of that group, 61 percent reported performing this procedure without explicit patient consent. At most university-affiliated hospitals, patients sign consent forms that vaguely allude to medical students’ involvement in “their care,” language that protects the hospitals from liability. At New York–Presbyterian Hospital, the primary hospital affiliated with Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, patients sign a consent form stating that “other practitioners may assist with the procedure(s) as necessary, and may perform important tasks related to the surgery.” Medical students are not, legally, “other practitioners,” and thus are not included in their consent form at all.

In our survey, some students responded extensively about their experiences with exams under anesthesia (EUAs), writing paragraphs and, in one instance, even pages. They want the educational benefits; they feel uneasy with hospital norms; they advocate for one position before undermining it in the next breath. A minority, 11 percent, are extremely uncomfortable with the practice. Of the students who’d performed the exam, 49 percent had not met patients before performing the procedure. Nearly a third of respondents admitted they hadn’t read their hospital’s consent forms.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ opinion is that “pelvic examinations on an anesthetized woman that offer her no personal benefit and are performed solely for teaching purposes should be performed only with her specific informed consent obtained before her surgery.” And, according to ACOG, “informed consent should be looked on as a process rather than a signature on a form.”

At Harvard Medical School, students on their ob-gyn rotation perform about five pelvic exams on unconscious women during a six-week rotation. With a class size around 165, as many as 825 pelvic exams are conducted by Harvard students on anesthetized women annually. “It’s a standard consent form, not very specific,” says one student. “And I think it’s resident-dependent on how much the EUA is explained.” When she’s been present, the EUA has not been explained.

Eight states (California, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia) have outlawed nonconsensual pelvic exams, and this week, New York state became the ninth. In March, assemblywoman Michaelle Solages (D–Nassau) and state senator Roxanne Persaud (D–Brooklyn) introduced the legislation. When Solages gave birth at a Long Island teaching hospital last fall, she was put under anesthesia during labor complications. When the bill came across her desk, she realized it was impossible to confirm it hadn’t happened to her. EUAs are not recorded. The legislation will outlaw the practice in New York and require hospitals to document these educational exams when patients do consent.

Since the March announcement, her constituents have emailed her, called her, and stopped her on the street to express their horror. Some are survivors of sexual assault and abuse. “They don’t want to give consent [to students], and we need to respect that,” Solages says. “Women should have control over their bodies.”

The idea of medical students performing nonconsensual pelvic exams on women under anesthesia shocks people outside of medicine. Inside medicine, most view it as routine. “The patients have no way of finding out what happened during their procedure, and they’ll come out none the wiser,” says Kayla, a fourth-year Yale student. “It felt a little weird that I was doing this on somebody anesthetized, but it was the best opportunity I had to practice.”

Katie and I are sitting in a third-floor classroom at the Yale School of Medicine, where she’s halfway through her MD/PhD program. I added an MD to my name in May, and start an emergency medicine residency here this month. Our progress should be cause for celebration, but our education thus far has been filled with discomfort. Our understanding of consent and bodily autonomy hasn’t yet filtered into the medical community we’re joining. Katie, now 31, has a big laugh, a beaming smile, and a fierce ethical code. She’s a survivor of sexual violence and has worked in grassroots reproductive-rights advocacy. Still, she performed that pelvic exam in 2016.

As medical students, we’ve been taught to depersonalize a host of otherwise unnatural experiences. We watch as chests are sawed open, cradle beating hearts in our hands. Private mysteries of life are unraveled and splayed naked before us. To accommodate the strangeness, we’re taught to approach patients dispassionately, taught to view them dissected. The abdominal exam, the same as the neurological exam, the same as the pelvic exam. Don’t make it weird. We’re doctors.

The night after his last day on a one-week urology rotation at New York–Presbyterian Hospital, Dominic* felt sick to his stomach. “Holy shit,” he thought. “I feel like I just sexually assaulted a patient.” He was a third-year student at Columbia University’s medical school, and he’d been given a list of tasks to complete during the week. Halfway through, during a meeting with his clerkship director, it became clear that some of the students had not yet performed a prostate exam.

She told them, “Come in at 11:15. Then you can check this off.”

When Dominic and a classmate arrived, the patient-an elderly man-was already under anesthesia. He was likely receiving a prostate reduction or removal, but no one ever explained the procedure to Dominic or told him the man’s name. Dominic scrubbed his hands clean. Then he and the other student performed prostate exams, one after the other. Then Dominic left. He thinks it’s possible that five or six other students performed the same maneuver, on the same man. “I felt like we had just done something really, really sneaky,” he thought afterward. “That I had to violate a patient’s bodily autonomy in order to check off a requirement for a pass/fail one-week rotation is absurd.”

Many trainees view EUAs (both pelvic and prostate) as integral to their clinical education and extremely appropriate. Others, like Katie and Dominic, remain appalled. Dominic would “absolutely not” allow medical students to perform prostate exams on him if he were ever anesthetized for prostate surgery. “It feels very dehumanizing,” he says, to be made into a teaching tool without your say. Last year, a group of students starting their Columbia urology rotation asked him for tips. “Yeah,” Dominic said, “don’t assault anybody.” (Columbia University has not responded to requests for comment.)

Unfortunately, medical students can’t always say no. In our survey, nearly one-third of the respondents felt unable to opt out of performing these exams. Since supervising residents and attending physicians write evaluations, students fear jeopardizing grades and future careers. “I tried to opt out once from doing a pelvic exam when I hadn’t met the patient beforehand,” says one senior Yale student. “The resident told me no.” At the University of Michigan Medical School, “they taught us it was important to ask forgiveness and not permission,” says another student. For one at Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School, the pressure was also social. She describes EUAs as a ritual: “Everyone’s gloves were handed out, then lubrication was put on those gloves in succession,” she says. “In the moment, I felt like I was being accepted into the ob-gyn culture.” (Yale and Brown have not responded to requests for comment. Harvard stands by its consent policy.)

When Phoebe Friesen, a former ethical adviser to New York medical students, first heard about EUAs, she was horrified. But when she broached the subject with faculty, she was told that as a nonphysician, she’d never understand what was necessary for students to learn. She was told she was overreacting. “There is no scandal,” echoed one student from the Washington University School of Medicine, who insisted that current consent processes are effective. “Poorly informed activists and media outlets are seeking to invent one.” Individuals in the medical field are understandably defensive. They’re just doing their jobs, and medically, pelvic exams before surgery are crucial. In our survey, many students reasoned that since patients are at teaching hospitals, they understand students will be involved in their care. “There’s a degree of implied consent,” says another Washington University student. But Katie refutes that logic. “Many patients don’t even know what an academic medical center is,” she says. “And when patients are taken by ambulance, they may have no choice in where they go. They’re taken to the nearest hospital.” (For example, of the 15 facilities where Harvard Medical School students complete clinical rotations, none reference Harvard by name, since the university doesn’t own or operate any of them. They are, nonetheless, teaching hospitals.)

In a 2010 Canadian study, only 19 percent of women reported awareness that medical students might perform pelvic examinations on them during surgery. “The vast majority of women say, ‘I do care; you should ask me,’” says Friesen, who’s been writing about the topic for the last five years, now in her role as a University of Oxford bioethicist. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in three women in the United States have experienced sexual violence. Medical care does not exist in a vacuum. When students are not taught to ask-or taught not to ask-patients for permission, it instills entitlement to enter the body.

Conscious patients can decline educational exams, and that right should continue to be enforced under anesthesia. According to the 2010 study, 72 percent of women expect to be asked for permission before an EUA. If patients are not aware that medical students will be performing exams on them, they have not provided consent. So although the examiner may find a pelvic exam impersonal and trivial, patients may not, and the violation is theirs to bear.

There are easy fixes to this situation. Some schools are changing their standards, like the University of Michigan, which earlier this year implemented a new policy requiring medical students to meet patients before performing pelvic EUAs, and requiring doctors to explain student involvement. The same Canadian study also found that a majority of women (62 percent) would agree to educational EUAs if asked. Assemblywoman Solages would do so herself. “We want to encourage the next generation of medical and health-care professionals,” she says. “But at the end of the day, consent is just right.”

When I walk into the Center for Sexual Pleasure and Health in Providence, Rhode Island, to interview Cheylsea Federle, I can’t help but grin. Federle, the organization’s education and training coordinator, has a blond shoulder-length lob and a disarming smile. Beside her is a crystal bowl brimming with a Skittles-colored array of condoms and dental dams, and next to that, a fabric puppet of a vulva, anatomically complete with a button clitoris. A few times a year in her role as a gynecological teaching associate (GTA), Federle instructs Brown University medical students on how to perform pelvic exams, using her body as a textbook. She’s thrilled to show students her cervix. “If you don’t feel it, keep going,” she encourages students. “I let them know: ‘Take your time; I’m good!’ ”

Within medical schools, GTAs are commonly hired to teach pelvic and urogenital exams to students before they begin clinical rotations. Many, like Federle, are intentional about teaching students to be mindful of power dynamics. Doctors often seem inaccessible and busy, she says, and patients assume they’re not supposed to ask questions or request adjustments. GTAs show students what it looks like-and how appropriate it is-when patients actively participate. “There’s so much value to getting real-time responses,” says Maric Brandi, a Boston-based sex educator. “What I teach is maybe 50 to 60 percent anatomy and physiology, and closer to 40 percent how to take care of your patient and how not to accidentally be weird when you’re doing a pelvic exam.” Brandi cites studies demonstrating that students who train with GTAs before rotations are more skilled: “They talk to patients more easily, and they tend to give more comfortable, relaxed, and pain-free exams.”

But students change between the convocation and commencement of medical school. There is a cost to gaining a white coat. One student referred to her justification of hospital norms as “Stockholm Syndrome setting in.” A 2003 study of Philadelphia medical students found that trainees who had completed an ob-gyn rotation viewed consent as significantly less important than those who hadn’t yet done so (51 percent, compared to 70 percent). This transformation doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s learned; it’s taught. When Kayla was turned away by a patient during a preoperative meeting, her Yale resident pulled her aside. “They don’t have the choice,” he told her. “You have the right to be there.” At Yale’s affiliated hospitals, pelvic EUAs without consent are still legal. “The inability to understand that a third of women have been victims of sexual violence, the inability to think about that and respect that, is unbelievable,” Katie says. “It is unbelievable that it’s 2019 and this is something we’re talking about.”

*Names have been changed.

This article will appear in the August 2019 issue of ELLE.

('You Might Also Like',)