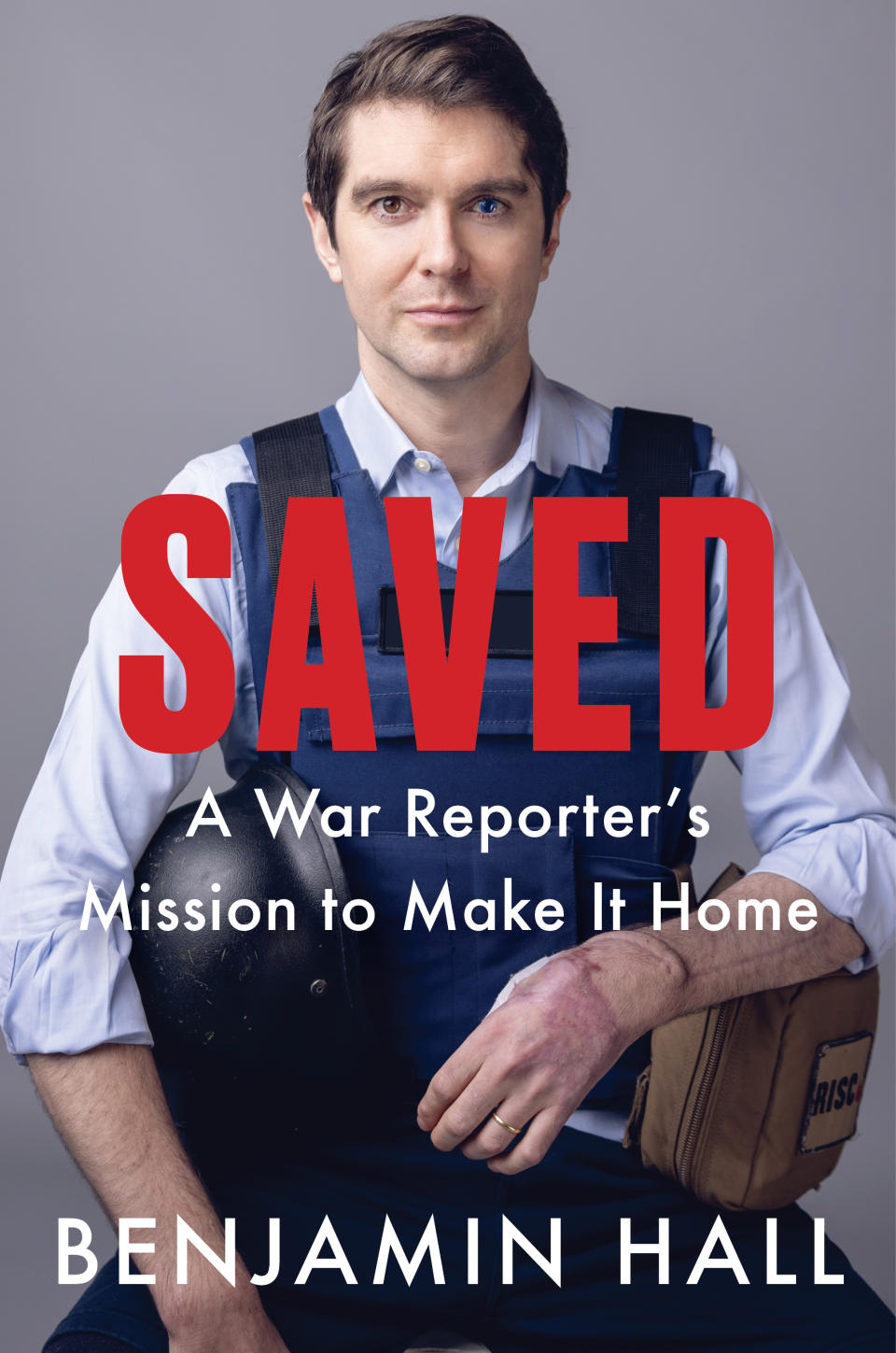

Media People: Benjamin Hall’s Harrowing Journey to Save Himself

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Was the dead dog an omen?

It was March 14, 2022, one month into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s brutal incursion into Ukraine. Benjamin Hall, a seasoned war correspondent though not yet 40, was in the back seat of a little red car, rattling down an abandoned road on the outskirts of Kyiv. Two Ukrainian soldiers were in the front. Hall, who joined Fox News in 2015 as a foreign correspondent based in London, was jammed into the middle seat in the back, between Sasha Kuvshynova, a 24-year-old Ukrainian fixer, and Pierre Zakrzewski, 55, a veteran photographer who had covered dozens of international stories for Fox News.

More from WWD

As they drove through a deserted checkpoint in the village of Horenka, Hall saw a dead Alsatian on the road and thought to himself: “Poor dog. Who killed the bloody dog?”

Minutes later a bomb exploded 30 feet in front of their car, igniting a stand of trees on the side of the road. And then a second bomb, and then blackness.

In his new book “Saved” (HarperCollins), Hall describes what happened next. He heard the voice of his eldest daughter Honor, then six years old: “Daddy, you’ve got to get out of the car.”

When the blackness receded, Hall somehow managed to extricate himself from the car, which contained the remains of the Ukrainian soldiers and Sasha. Pierre was still alive and lying on the ground several yards from the car. Hall’s legs were on fire, so he started rolling his body and patting his legs to put out the flames. Then he realized half of his right leg was missing and his left was severely maimed. He took a photo of his legs with his cell phone, which he had somehow located, though he had no reception. His left thumb was hanging by a flap of skin and he had shrapnel in his neck and head. He stumbled toward Pierre and away from the car.

Then, on the road above, a car drove by. Hall yelled. The car kept going. He realized the occupants of the car could not see him because he was at the bottom of a slope, on the side of the road.

“I pulled myself along on my left side, clawing at the dry, orange dirt, moving inch by inch,” Hall writes. He was thinking of his three young daughters. He managed to drag himself up the hill and sit up. The same car came back from the other direction.

“I waved at it and grabbed dirt in my hands and threw the dirt at it and yelled out and did everything I could to make whoever was driving the car see me.”

The car stopped.

What makes someone run toward disaster and mayhem, while most of the rest of us instinctively run in the opposite direction? Hall’s book — which comes out Tuesday, exactly one year after the day he willed himself up that slope so he could be seen and rescued — attempts to answer the question that has vexed families of war journalists for generations. (The Committee to Protect Journalists estimates that 15 journalists were killed in Ukraine last year, and many reported being deliberately targeted by Russian troops.)

Hall’s motivations are intertwined with family history. His father, Roderick Hall, was born to a Scottish father and Filipino mother in Manila. Roderick was 12 years old in 1941, when the Japanese invaded the island nation, consigning Roderick’s father (Hall’s grandfather) to an internment camp. Roderick never saw his mother, grandmother, aunt or uncle again; they were presumed killed. For the next three years, Roderick took care of his siblings. And when Gen. Douglas MacArthur stormed the beaches and liberated Manila, Roderick and his siblings were saved by soldiers from the 37th Infantry.

Roderick settled in America, where he graduated from Stanford, and in 1954, feeling an almost devout dedication to the U.S. and her military, enlisted to serve in the Korean War.

“My fate,” writes Hall, “would not be to fight in wars, but to be a war correspondent. I went wherever civilization was collapsing under the assault of factions and ideologies.”

That included Aleppo, Mosul, Kabul and Mogadishu. In 2011, during the last throes of the brutal reign of Muammar Gaddafi, Hall snuck into Libya with his best friend and fellow conflict addict Rick Findler. One day before they departed, photographers Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondos were killed in Misrata by a mortar shell.

“I liked being there,” he writes of conflict zones (emphasis his). “It made me feel alive.”

But the equation changes when you have a family. And by the time Putin invaded Ukraine, Hall had transitioned out of war coverage and was working in the Fox News Washington bureau as the network’s State Department correspondent. He was living in temporary housing in Washington, while his wife Alicia and their three daughters — Honor, Iris and Hero (who are now seven, five and three) — remained in London with plans to move to Washington after the school year ended. (Hall, whose mother is British, grew up in London and is a citizen of the U.S. and the U.K.) He is still on medical leave from Fox News and plans to resume his journalism career but is still very much working through his recovery. After 15 years of covering wars, he wants to focus on “positive, uplifting stories.”

Being a war journalist, Hall says during a recent Zoom call from his home in London, “was the purest form of journalism in my eyes, because it really was life or death. I wanted to go out into the world and see the very extremes of human experience. And then that started to change. And I started to understand the real human implications of wars.”

Still, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is a war unlike most of us have seen in our lifetimes. It isn’t a rebel uprising in a far-flung country. It is an invasion of a sovereign country on Europe’s doorstep. So when Hall got the call from his Fox News bosses asking him if he would go to Ukraine, he did not hesitate. And his wife did not ask him not to go.

“My wife and I continue to talk about this today,” says Hall, laughing a little. “What were we thinking at the time? At its purest, it was something that I felt was so important — to go out and tell the truth about what was happening there. I knew I was going to do it to be honest.”

After Hall was pulled off that desolate road by a convoy led by a Ukrainian special forces agent who goes by the codename Song, he was taken to a combat hospital in Kyiv. (Song checked on Zakrzewski, but he had died; he took Zakrzewski’s camera.)

In Kyiv, doctors treated Hall’s injuries as best they could, which included amputating what was left of his lower right leg. The most gripping chapters in “Saved” detail Hall’s harrowing extraction from Kyiv, which, at the time, was under lockdown with Ukrainian forces authorized to shoot anyone in the streets. (Fox News Channel will debut a two-hour documentary “Sacrifice and Survival,” about Hall’s rescue and ongoing recovery March 19 at 9 p.m.)

Hall recounts the relentless efforts of colleagues — especially Fox News Corp.’s chief national security correspondent Jennifer Griffin and an army of strangers, who would offer critical aid in getting Hall to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany within 48 critical hours of the attack. Sarah Verardo, cofounder of the nonprofit Save Our Allies, enlisted a mysterious operative called Seaspray — a former U.S. intelligence officer who helped evacuate thousands from Afghanistan during the 2020 chaotic U.S. pullout.

Seaspray and a team of operatives got Hall to the Polish border, 800 miles away from Kyiv, where he was able to hitch a ride on the train belonging to the Polish prime minister, who was in Ukraine for a clandestine meeting with President Volodymyr Zelensky. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and then-Pentagon press secretary John Kirby worked diplomatic channels with the Poles. Once in Poland, Hall was evacuated via a Black Hawk helicopter to Landstuhl. He endured numerous operations there before being transferred to the Brooke Army Medical Center near San Antonio, Texas. (He endured an arduous 24-hour journey aboard a C17 transport aircraft to Texas.) Hall spent six months at BAMC, where Col. Dr. Joe Alderete, the chief of surgical oncology, would lead his medical team.

A month into his time at BAMC, Hall began to record a video diary that would become the basis for his book. He pieced together his extraction from Ukraine, when he was in various states of consciousness, through conversations with his Fox News colleagues and Seaspray, who came to visit him at BAMC. Verardo and Griffin supplied details from the other end of that effort; it was Griffin who enlisted Kirby to intervene with Secretary Austin. Every few weeks, Hall would learn about someone else who offered help along the way.

The process, he says, was “cathartic.”

“These pieces were coming at me and I kept learning more about what had happened. And that was the part of the book that I thought was the most fascinating; all these incredible people who came together to save me.”

Of course, Hall also managed to save himself. He was burned over 17 percent of his body (luckily less than 10 percent were third-degree burns). He’s had skin grafts with donor skin and his own skin; most of his own back was stripped of skin for grafts. His thumb metacarpal had been shattered, much of the thumb was missing and muscles and cartilage had been torn out; surgeons repaired his thumb with a flap of skin from his elbow.

A couple days after surgery, blood was flowing to to his hand but not draining, so they administered leeches. He had a tube inserted in his left eye to drain fluid from a defecting corneal transplant. Then doctors inserted a special contact lens and sewed his eye shut. His right leg, which had been amputated below the knee, only left him with five inches of tibia, two inches less than optimal in order to attach a prosthetic. His left foot had a hole blown through it, essentially leaving him with only the heel, so he needed a partial foot prosthetic. And then he developed septicemia (pathogenic bacteria in the blood stream) causing fever, chills and aphasia.

At BAMC, Hall underwent dozens of operations and was administered medications more than 5,600 times, from eye drops to plasma, IV drips and painkillers, which caused frightening hallucinations.

Doctors estimated that he could be at BAMC for two years. But six months after he was admitted, he was strong enough to go back to London and his wife and children.

“When I found myself at the real bottom, when the pain was really bad, when it felt miserable, I told myself that things would be better, that I could control the pain,” he says. “And I amazingly found that I could do that, that I could focus [my] mind. And I realized that we are much more in control of our feelings and our body than we ever give ourselves credit for. I think there is a deeper level inside all of us.”

For Hall, perseverance is a savior.

“If you’re going through something that is difficult, always know that there is a way through that. There is a way to find light on the other side. If you want to find it, it’s there. I feel so much stronger now than before. Because if I can’t make the best of every single second, I will have wasted my life, Pierre’s life, Sasha’s life and wasted everyone else’s life who is gone. I didn’t lose a leg. I didn’t lose a foot. I gained life.”

Best of WWD