How Can We Measure Black Joy?

Black Joy is resistance, it's self-love, it's rest—it's everything. But how do we know how much we have?

Illustration by Eliana Rodgers for Kindred by Parents

One of life’s biggest questions is how to measure satisfaction, content and fulfillment–the foundations that conjure joy. Firstly, it should be noted that joy is interchangeable with happiness and positive well-being. Secondly, it’s hard to define and quantify joy generally, but it becomes more of an obstacle when characterized from a Black perspective. Despite the presence of systemic racism, police brutality, economic inequality, and other factors, higher levels of happiness are reported among Black people compared to white people. So how can we better understand Black joy?

If we look at happiness from the perspective of Harvard researchers who conducted a study over decades, we find that the key to joy could be embracing community and social relationships. This is important, especially for Black people. We have experienced a myriad of complex challenges based solely on our race with shared disappointments and shared triumphs. From these, we’ve developed a unique culture of community that encompasses Black joy. Importantly, these are safe spaces. Black churches, Black fraternities and sororities, and family cookouts, are examples but also organized activities such as Black brunches, Black parties, Black hikes are ways in which we experience and cultivate joy. Black joy is about togetherness.

Catherine Knight Steele, Director of the Black Communication and Technology Lab at the University of Maryland, agrees. “Black joy is less about having things to be happy about and more about the process of creation and recreation. Joy emerges historically through our relationships with each other and our ability to create community.”

This feeds into how Black joy relates to Black families through community. “Black families–like Black joy–are a product of that creation and recreation. The beauty of Black families is how Black folks have demonstrated ways to stay connected or create new connections even in the midst of concerted efforts to tear us apart,” Steele says. “In the same way we strive to keep connected to existing families and build chosen families, Black joy is an intentional process that chooses hope, chooses community, chooses exuberant demonstrations through our communication with one another.”

This is supported by a 2023 study that revealed Black mothers are equally as happy as Black women without children, however white mothers are significantly less happy than white nonparent women. Furthermore, Black fathers report more happiness than their nonparent male counterparts. This demonstrates the importance of family for Black people, despite the negative stereotypes surrounding Black mothers and fathers.

The perspective of Black community being synonymous with Black joy further ties into research that suggests that loneliness poses serious health risks. A recent report by the US Surgeon General found that lacking social connection increases the risk of heart disease by 29% and stroke by 32%. It also increases the risk of premature death by nearly 30%. As one study highlights, collectivism and unity are highly regarded “afrocentric values.” Given that Black people have historically been pushed out of society, this has encouraged Black communities to pull together.

Illustration by Eliana Rodgers for Kindred by Parents

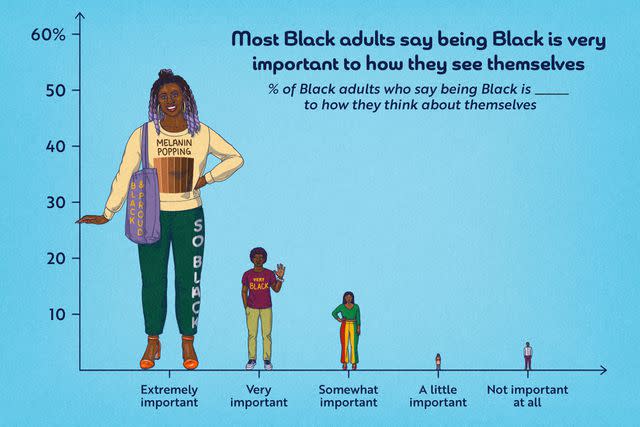

A 2011 study found that “the more the participants identified with being Black—or the more being Black was an important part of who they are—the more happy they were with life as a whole.” This was reiterated in 2022 when Pew Research found that for Black Americans, race is integral to identity and affects how they connect with one another. This could indicate that the ability to identify with Blackness and Black culture itself brings joy and could help quantify it. Steele emphasizes that this is essential because through Black culture “our language, music, humor are constantly changed, renewed and updated and therefore can't be taken away.”

A researcher from the University of Warwick outlined several ways to evaluate happiness including good health and having money. While true from a general perspective, when you look at it from a Black point of view, those metrics sometimes don’t correlate. For example, studies show that white Americans live longer than Black Americans and that Black Americans are at greater risk of serious health conditions compared to other racial groups. Black Americans are also systematically undertreated for pain which contributes to worse care. Despite proven disparities in health outcomes based on race, one study found that there is a weaker link between good health and happiness in Black Americans, meaning that unhealthy Black people are still more likely to self-report as happy.

It’s also well-documented that economically, Black people struggle more. This is due to persistent inequality issues such as generational poverty, the wage and wealth gap, and lower homeownership rates, yet a study from 2018 found that poorer Black people are happier and more optimistic than poor people of other races.

While health and money may not help quantify Black joy, this research shows that there may be higher levels of resilience and optimism amongst Black people which could be key metrics for quantifying Black joy. “Resilience is built into the history of Black folks across the diaspora. That is just a fact,” comments Steele. “You can look at the way Black discourse emerges from oral cultures, how pidgins and creoles develop on this continent, how signifying moves from off to online spaces.”

“Consider how Black folks whose communal conversations were once housed on certain social media platforms are migrating and moving as those sites transform into places too frequently hostile to hold space for joy. Who we are and how we create joy requires resilience,” she continues.

Research further shows that mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety are found to be less prevalent in Black Americans than white Americans, which could be linked to resilience. A 2022 study reiterated this, suggesting that “Black Americans have lower rates of depression and anxiety than whites, despite greater exposure to stressors known to negatively impact mental health”. As a caveat, this could also be due to Black people having protective factors from childhood that somewhat shield them from the negative effects of stress.

Progression could also be another way to quantify Black joy. Shared goals such as equality and addressing systemic racism matter greatly. For example, despite being persistently lower than white people and varying across the country, the life expectancy of Black people has increased which indicates progress. Voting rights, educational attainment and policy changes are just a few examples of ways in which Black people have made strides forward over decades—collectively. We can no longer be silenced and many of the cruel ways in which racism presented itself are no longer openly acceptable. Though progress has plateaued with less gains and wins, this is still tangible growth over a long period of time that can help to quantify Black joy.

In its purest form, Black joy is also about moments of feeling good and free. It’s about surviving and living through unwavering optimism (which is associated with longevity). It’s about smiling and laughing. Though hard to quantify, laughing itself has been shown to be a coping mechanism among Black people.

While there are a number of indicators that can help quantify joy generally, it seems like Black joy largely stems from community and culture. It’s not based on individualistic ideals—it’s founded on collectively lived experiences, which is what makes it so special.

It’s a rejection of the onslaught of never-ending images and stories of Black pain and trauma that seem more prevalent and visible than joyous depictions. Black joy is radical and it is a form of resistance, reclaiming the freedom to be who we are with pride and passion–unapologetically. That freedom also means leaving behind the feelings of burden that come with being Black and finding security and comfort in collective happiness.

“There is a real connection between joy and hope in Black communities,” says Steele. “Hope and joy aren't naive–they are a product of a deep awareness of what is necessary to not simply survive but thrive. While I embrace and study this resilience and optimism, we shouldn't ignore the labor and exhaustion of those ideals and goals. In doing that we make space for the kind of Black joy that can also develop from refusal and rest.”

For more Parents news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Parents.