Can Matronage Shift the Art World’s Gender Imbalance?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

A patron of the arts is a person who loves and supports creative work. But since the term patron comes from the Latin word for father, it’s an inaccurate term for non-male arts advocates. Of course, male-gendered language is so ubiquitous, we often don’t notice we’re using it. (The word virtue, for example, comes from the Latin vir, for man. Even the city of Philadelphia is male—adelphos means brother in ancient Greek.)

Given the early history of arts patronage by kings, emperors, and popes, the gendering of the word isn’t surprising, but it brings to mind an important question: Does the fact that we implicitly think of the art collector and supporter as male have a bearing on the dismal statistics around representation of female visual artists?

As the founder of Less Than Half, an education and advisory platform raising the profile of female artists, I see enormous potential to change those numbers, by teaching women to claim the label “matron of the arts” and support those artists. Not only are women currently in an unprecedented financial position to invest in female artists, they also tend to spend more on art than men.

According to a 2020 McKinsey report, women are poised to inherit two-thirds of wealth handed down by baby boomers as part of what is being called the Great Wealth Transfer. And though the COVID-19 pandemic certainly set many of us back professionally, women have recovered those losses and are on track again, moving up in the corporate and entrepreneurial worlds: Representation of women in the C-suite has increased 65 percent over the last eight years, 49 percent of new companies in the United States are founded by women, and, for the first time in history, more than 10 percent of Fortune 500 companies are led by women. Imagine if this societal shift in wealth distribution, as well as current buying trends exhibited by female collectors, could be harnessed in service of changing the art world’s appallingly off-kilter gender imbalance.

In major museum exhibitions in the United States between 2008 and 2020, only 15 percent of the work presented was by female artists. In other words, you are roughly seven times more likely to see an exhibition by a male artist in a museum than one by a female artist, and you’re 16 times more likely to see a show by a white male artist than the work of a Black American artist.

In the market, it’s even worse. Female artists generate 3 percent of auction sales—and just 0.1 percent of all sales are generated by Black American women. Records at auction for women are roughly one 10th that of men: The highest price paid for a piece by a living female artist, set by Jenny Saville’s Propped in 2018, is $12.4 million—compared to Jeff Koons’s record for Rabbit, $91 million. Georgia O’Keeffe holds the record for a historical female artist with the sale of Jimson Weed for $44 million, a mere fraction of what Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci famously sold for: a staggering $450 million.

Women, however, are statistically more likely than men to be trained as artists (a 2015 analysis from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Humanities Indicators shows that around 70 percent of MFA graduates in the U.S. are women), making the tired excuse “It’s a pipeline problem”—used by so many to try to erase the need to address gender inequity—insufficient.

But equal representation in art is not only a matter of fairness. Making art, after all, is a uniquely human pursuit, common to all people in all places across all of history and before. Art doesn’t fill an everyday need for survival, but spiritually, it describes what it is to be a human being. So what does it mean for us as a culture if women are not included in museums and collections? By denying them spots in the gallery, do we not implicitly state that their humanity is not worth celebrating and preserving for posterity?

Matronage, as I define it, is not a matter of simply buying female artists rather than male artists (provided you have the cash to do so in the first place). Matronage is an insistence that women matter, and it ensures its success by critically engaging with the systems that make the current numbers our grim reality.

As I advise my clients, a true matron of the arts supports women after those women have children, when many artist-mothers find the art world is not set up for them to succeed. “Questions of energy, sleep, your child’s health, focus, and access to resources impact one’s capacity to perform all the necessary touchpoints a successful career as an artist requires,” says Amanda Valdez, artist and founder of the First Ten, an arts program devoted to helping mid-career artists who are mothers advance.

Most art residencies don’t accommodate kids, a reality some are trying to address by creating parent-specific residencies, such as Stoneleaf Retreat, which supports “womxn and families.” And an artist-mother’s home turf can be equally inhospitable to children, as critic Hettie Judah explains in her 2023 book How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents): “The timing of the private [gallery] viewing to clash with the ‘witching hour’ of childcare [from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m.] is of course coincidental—it’s a hangover from the era in which gentleman collectors popped into the gallery … en route home from the office—nevertheless it broadcasts a set of preconceptions about who is important in this world.” The artist-mothers who skip such events, where crucial professional networks are built and maintained, can see opportunities dry up and relationships go stale. A matron of the arts will make a particular effort not only to buy art during this period of a female artist’s career, but also to keep her within the art world fold—on her schedule.

A matron of the arts will also gather and preserve documentation about the work she buys, as a way of addressing the dearth of biographies on female artists, especially female artists of color. “When cis and trans women … are not represented in archives and places like Wikipedia—the 10th-most-visited site in the world—information about people like us gets skewed and misrepresented,” says Kira Wisniewski, executive director of Art + Feminism, an organization working to close the information gap on gender in the arts. “The stories get mis-told,” she emphasizes. “We lose out on real history.” A thoroughly maintained archive ensures that future scholars and curators can develop an understanding of female artists and their work.

Proselytizing is also critical. A matron of the arts does not keep her collection to herself, but shares it widely. Whether that’s through social media, by lending to museum shows, or by organizing a private exhibition—as collector and matron of the arts Komal Shah recently did by staging “Making Their Mark,” a traveling exhibition of her collection—such promotion helps expose the artists and works to as large an audience as possible and inspires others to do the same.

A matron of the arts buys risky works, and maybe even finances an artist’s exploration of media that are less commercially salable, such as video or sculpture. She recognizes that experimentation is essential to innovation, on which art history is built, and that that inspiration is not immediately (or sometimes ever) apparent to the market.

She also thinks creatively about how artists are paid. She might consider alternative forms of financial support for artists, much like the famed gallerist Leo Castelli did when he kept his (almost entirely male) artists on retainer, rather than paying them when their work sold. Without Castelli’s patronage, we probably wouldn’t know the names Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, or even Andy Warhol. Which names will your matronage ensure become part of history?

If I’m losing you with the idea of buying art from intimidating galleries, investing in avant-garde art, or collecting work by artists destined for art history, stay with me. The art market, with all of its shock-and-awe auction records, is mostly made of artists selling for prices that wouldn’t make your jaw drop. When I advocate for more women buying art, I’m advocating for the seasoned collectors as well as the everyday art lovers. That’s why I teach women who have never bought art in their lives how to confidently navigate the art market, whether they are buying directly from local artists or bidding on a painting at Sotheby’s. This is a call to all women who can afford to put their money toward validating, celebrating, and making a legacy for female creativity.

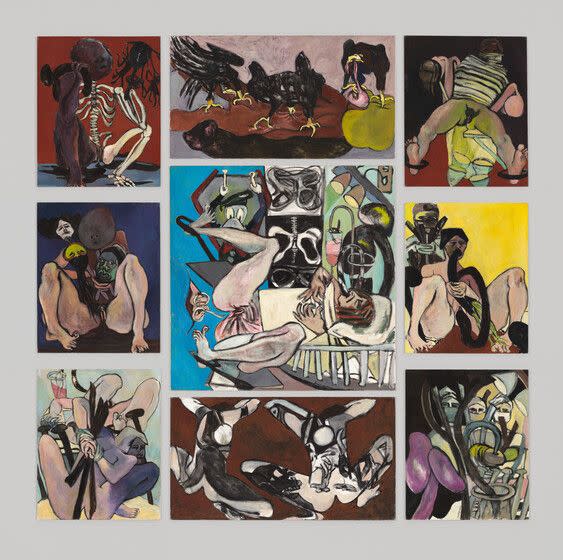

My philosophy of matronage makes a case for supporting female artists as a social and financial investment. The market for them may be small now, but a number like 3 percent means there is plenty of space to grow. And grow women will! Already, the data show the return on investment for female artists at auction is seven times that of male artists returning to auction, and the list of female artists setting personal auction records—from Julie Mehretu to Ruth Asawa—grows every auction season.

In 2022, the Whitney Museum acquired Juanita McNeely’s Is It Real? Yes It Is!—a monumental work depicting the artist’s harrowing illegal abortion in 1967. It entered the collection (the museum’s first painting depicting an abortion) after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the precedent established by Roe v. Wade and now hangs prominently in the Whitney’s permanent collection galleries.

I can’t help but wonder: If women’s experiences had been given this type of centrality, pathos, and understanding all along—not just by the Whitney, but by museums across the country—would we be where we are today, in less control of our bodies than we were 50 years ago?

Other hard-won rights can be taken from us. Let’s not wait to find out which ones they are. When we support, collect, and display the work of female artists, we are declaring that we are human. Otherwise, the world can forget.

You Might Also Like