A Math Genius Created the Decimal Point and Became a Legend. Turns Out He Stole It.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

The humble decimal point may have been invented about 150 years before we previously thought.

Experts had previously credited German mathematician Christopher Clavius for the innovation, but according to a new study, the credit actually belongs to Italian merchant and mathematician Giovanni Bianchini.

Bianchini’s work as a merchant likely inspired the mathematical leap, which then bled into his work as an astronomer.

There’s been a mystery lurking in one of the most unassuming parts of mathematics for centuries. When German mathematician Christopher Clavius introduced the world to the humble decimal point in 1593, he used it in one table, and never mentioned it or used it again in any of the rest of his writings.

Clearly, the decimal point is incredibly important to the way we do math today. So, why did Clavius abandon such a monumental discovery so soon after making it?

Because he stole it.

Well, “stole” may imply a bit more malice than is necessary. Let’s not read motive into 14th century mathematicians. But according to a recent paper published in Historia Mathematica, Clavius actually likely imported the decimal point into his own work when referencing the work of Italian merchant and mathematician Giovanni Bianchini from the 1440s.

Work that had been done almost 150 years earlier.

“In order to understand what Bianchini was doing,” Glen Van Brummelen, a math historian at Trinity Western University in Canada and the author of this new paper, told Nature, “you had to learn a completely new system of arithmetic.”

That’s because, back in the 1400s, astronomers and mathematicians used an entirely different numerical system to do astronomical calculations than we use now. Our number system today is built around the number 10. As such, it’s called a “base 10” system. Every number is made of a combination of 10 single digits 0-9, and every new “place” in a number represents 10 of the “place” before it. For example, a thousand is 10 hundreds, a hundred is 10 tens, and 10 is ten ones. It all comes back to ten, and it makes things pretty straightforward when it comes to operations like multiplication and division.

Easy, at least, compared to other systems. Because in the 1400s, astronomers and mathematicians used a base 60 number system, or a sexagesimal system, to do astronomical calculations. We can still see remnants of this system in things like time (1 hour is 60 minutes and 1 minute is 60 seconds) and degrees of a circle (one circle is 360 degrees around, one degree is 60 minutes, and one minute is 60 seconds). But instead of relegating the base 60 system to just a few oddball mathematical areas, all astronomical calculations were done this way.

And that made things very messy. Look at it this way: in a base 10 system, you divide 104 by 2 the exact same way you divide 10.4 by 2. Just cut all the numbers in half. But in a sexagesimal system, 10.4 doesn’t read like 10.4. It has to be converted into a very complicated fraction, dealt with, and then convert it back out to get an answer that we can understand.

Messy. But messy is the driving force behind innovation. And Bianchini had one sneaky advantage that had him poised to be the one to make this particular innovation: he wasn’t just an astronomer. He was a merchant.

Merchants, in their day to day lives, didn’t need to worry about base 60-style numbers. They just needed to deal with numbers that we would interact with in trades—small quantities and partial pieces. For his merchant work, Bianchini invented a system where he divided measurements into ten parts and noted those parts with a decimal point.

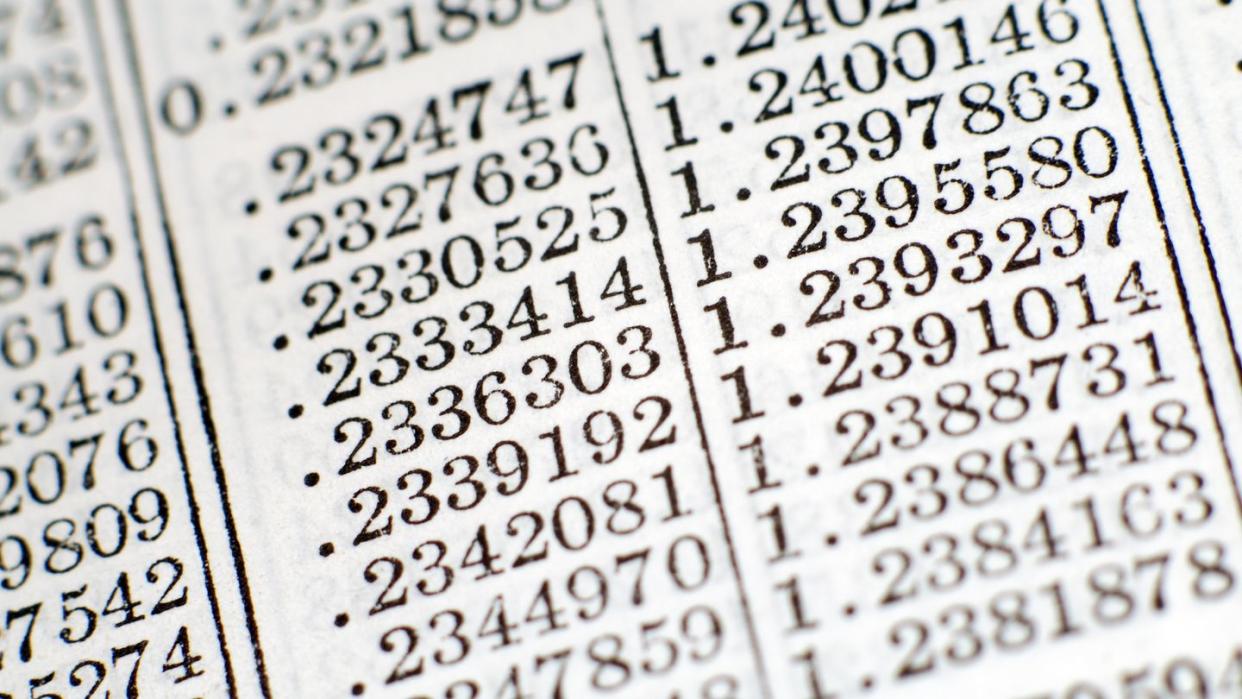

And he ported them over into his astronomy. When poring over some of Bianchini’s work, Van Brummelen came across the number 10.4, written with the decimal point and an explanation of how to multiply the number by 8. Further on in his text, Bianchini wrote out a trigonometric table of sines in which he uses his decimal system liberally. He also leaves instructions for what the point means and how to use it in the context of the table.

“I realized that he’s using this just as we do, and he knows how to do calculations with it,” Van Brummelen told Nature. “I remember running up and down the hallways of the dorm with my computer trying to find anybody who was awake, shouting ‘look at this, this guy is doing decimal points in the 1440s!’”

Over the course of his lifetime, Bianchini wrote at least five major works. These were substantial, and would have survived long past his death—easily to the time when Clavius was working on his own astronomical calculations. “[Clavius] had access to Bianchini's Sine table (or to someone who himself had borrowed from Bianchini), and he copied the structure of that table in his own work,” Van Brummelen wrote in his study. “While Clavius was composing the Astrolabium, a sophisticated work in spherical astronomy, Bianchini and Regiomontanus would have been very familiar names to him and his colleagues.”

The decimal point may still not have caught on for some time, but it has now become absolutely fundamental in the world of mathematics. Without it, our current monetary system wouldn’t work as it does, and we couldn’t make calculations to the degree of accuracy we need to puzzle out the secrets of our universe.

And it turns out that phenomenal contribution can be traced back a lot further than we thought. Hats off to you, Giovanni Bianchini. Thanks for the math.

You Might Also Like