The Masterful Western That Helped Make Matthew McConaughey a Star

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

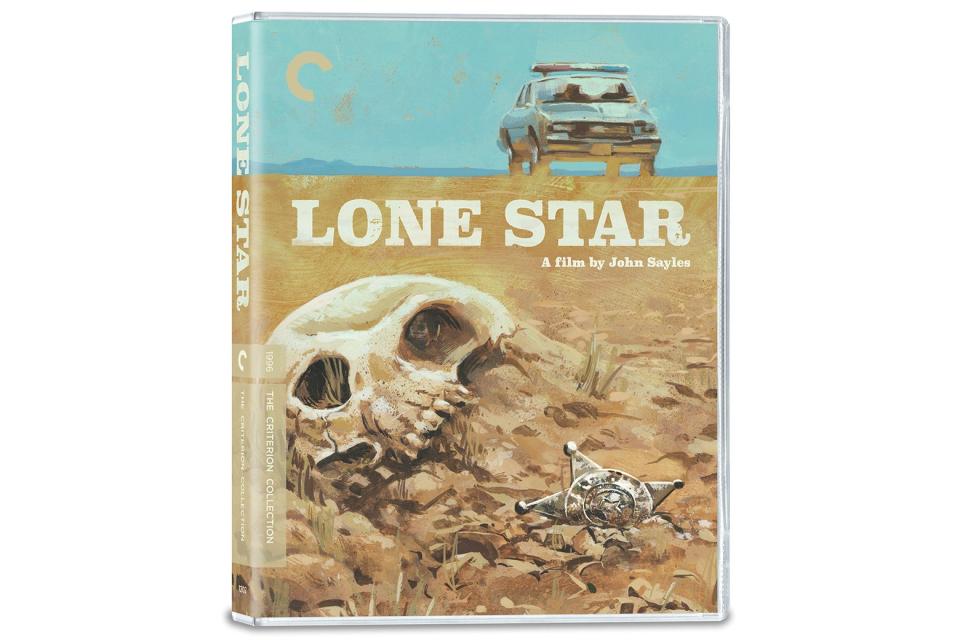

In his long career as an independent writer-director, John Sayles has never had a success like 1996’s Lone Star, which was financed immediately, supported in its release, and seen by a relatively wide audience. He even received an Oscar nomination for the film’s masterful screenplay, which slides from the past to the present in a Texas border town. In the 1950s, deputy Buddy Deeds (a young Matthew McConaughey) faces off against a racist sheriff (Kris Kristofferson). In the 1990s, Deeds’ son Sam (Chris Cooper), now the town’s sheriff, investigates a skeleton found outside town—along with a rusted Rio County police badge. When Sam reencounters his high school flame (Elizabeth Peña), it becomes clear that secrets from the past can’t stay buried forever.

Thoughtful, elegantly structured, and evenhanded, Lone Star interweaves stories of the border’s Anglo, Tejano, and Black communities. This American independent landmark is now joining the Criterion Collection, and I talked to Sayles about how he assembled the movie’s stacked cast, how he shot the film’s elegant mixing of the past and the present, and what’s happening at the Texas-Mexico border these days. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dan Kois: Last time I talked to you, it was about Matewan, which was a real battle to get financed. Lone Star happened at a different time in your career. You had made more movies, and you had an Oscar nomination under your belt. Was this one easier to finance, or were you paying for it from the money you got rewriting Apollo 13?

John Sayles: We got lucky. We got to make it fairly shortly after I wrote it. Castle Rock got interested in Lone Star, and Castle Rock had been on kind of a winning streak. Rob Reiner, who I’d worked for as a writer, had had some successes. Billy Crystal was working with them. They just believed in the movie. When it came out, they spent more money than anybody has ever spent on one of our movies before. So it is the most seen of any of our movies in a movie theater.

I remember when I saw this movie in the theater, it was right as Matthew McConaughey fever was sweeping the nation. How did he end up in this one?

I had seen him in Dazed and Confused, and I knew Rick Linklater, who told me Matthew wasn’t an actor, he was a film student—but he had so much charisma Rick kept expanding the part.

Wooderson just got bigger and bigger.

Right. I needed a guy who knew how to wear the boots and the hat and could have a confrontation with Kris Kristofferson without standing up, and I thought he could do it. By the time we did the wrap party, Matthew had gone and auditioned for the next movie, the one that kind of made him a star. I forget which one it was.

It’s A Time to Kill, I think.

Right, A Time to Kill. But we kind of just had this feeling. Oh, this guy’s going to be around.

Well, he is very believable as someone who’s going to turn into a legend, which is the point of the role.

And that nice combination of a comfort in front of the lens, which you certainly saw in Dazed and Confused, but also intensity when you needed it.

And Chris Cooper has that too, in a slightly more subdued way.

Chris probably would be a good sheriff. Even if he didn’t like the job, he’d probably be a pretty good sheriff. It’s like Frances McDormand. I remember seeing a movie where she was supposed to be playing the head of intelligence or something like that, and I said, Well, Frances could do that, and it’s just the quality she has. You believe that. And then she came down and did a day on this movie, a very different part for us, and she can turn that on too.

She plays Chris Cooper’s ex-wife, a high-strung football fan. She just did that all in one day?

Oh, yeah. It was just pure adrenaline.

I was really struck by Elizabeth Peña’s performance, seeing the movie this time around. That character’s so filled with yearning, but also so spiky, and the movie really does not work at all without a performance like that.

Liz was in a TV series that I wrote called Shannon’s Deal. She could do really heavy, serious stuff—she’d done a lot of theater—and she could do comedy at the same time. But also, there’s something really, really sensual about her—when she’d done sex scenes in movies or romantic scenes in movies, it was like, Wow, what a bombshell. But that’s not who she is—she also seems like she could be a high school teacher, a mom, all those things.

The movie shows a real commitment to investigating these three different communities in this town: the Black community, the Anglo community, and the Tejano community. How did you go about writing these communities? Were you doing research?

I’d touched on these kinds of communities in past projects. I’ve written various stuff, whether it got made or not, about the Brownsville incident. And then I had done stuff about the Mexican community in Texas too. I had hitchhiked down there and talked to local people.

And when we go to a place to shoot, I take the script and give it to some local people and say, “Is there anything that just wouldn’t happen here?” And you get some great stuff back. Some of it is just like, “Well, you can’t catch catfish in that season.” And then some of it is “I don’t think the guy would say that, because he would be sensitive about this local thing.” That’s one reason you try to shoot in the place, instead of just going to Toronto.

The movie moves between past and present with these complex pans in which a scene set in the past ends, and then we pan over and we’re back in the present. What was it like making those shots happen? It seems like a fun filmmaking challenge.

You have to tell your crew, “We’re going to do a complicated shot here, and I am committing to this shot. I’m not going to shoot any coverage.” And once they know that, all that work becomes fun because they know: Oh, we’re not going to go to the movie and find out that actually he cut away to the dog. Everybody gets into the act. The art department, as we’re panning, people are going to be changing clothes. They’re going to be pasting stuff on the wall to make it look like time has passed. We’re going to be easing the light down.

In one shot, Clifton James, who played the mayor, he was a big guy already, and he just said, “I don’t think I can get up out of this chair fast enough to get behind the camera when you need me out of the shot.” And so two grips came and grabbed the arms of his chair and lifted it and him out of the shot.

In a film, a cut is like a border. On this side, it’s one thing; on the other, it’s another. And I didn’t want that separation between the present and the past.

Immigration, both legal and illegal, plays a role in this movie, but it doesn’t overwhelm the story. There’s a lot of other stuff going on in this community. But right now on the Texas-Mexico border, it seems like immigration is, like, the only story. How did you think about that issue when you were making the movie, and how are you thinking about what’s happening at the border now?

I’ve been back there a couple of times, and truly the biggest difference is that there is a wall there now. When we were there, you took a dime and you put it in a slot and you went through a little turnstile and you were in Mexico and you went and had a margarita, and then you came back. People from Mexico did the same thing, and they went to Walmart and bought something, and then they came back in an hour. Not so easy to get across that river now.

Basically, the border is a human construct, and sometimes it becomes physical and sometimes it’s just a symbol. And that symbol has gotten so important politically to certain people who may not give a rat’s ass about whether Mexican people or Central American people come to this country and work for shit wages or not.

Who may even depend on it in some ways.

Yeah, exactly. But I can get some votes by stirring up a lot of fear about people coming in. Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras used to have really good relationships with each other. The mayors of the two towns had good relations with each other. Those became impossible when the federal government came in and started putting up walls. It really pushed those places apart—not only physically, but also psychologically. That’s a lot of weight to put on these little border communities.

What are you working on these days?

I have a novel that will come out about this time next year called To Save the Man, which is set at the Carlisle Indian School in 1890. And we’re trying to make a Western. I haven’t gotten other people’s money to make a movie in 20 years, and unfortunately even to make a small movie now you’re talking about $2 million, which I can’t just take out of my pocket. So we’ve been trying to raise money for movies for years and years and years.

Are you getting closer?

I hope so. You know, most directors don’t retire. They just stop getting financed or they die.