Marvel vs China: why even superheroes can’t beat Communist censors

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Chinese Communist Party has a new Undesirable Number One. No, it’s not a dissident investigative journalist or a free-thinking tech mogul. Instead, it’s a 12A-rated martial-arts superhero caper – Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.

The first standalone film in Marvel’s ‘Phase Four’ has received warm reviews and already stormed to more than $150 million at the global box-office, second only to Black Widow since the pandemic began. Yet it still hasn’t been given a Chinese theatrical release. This is despite that fact that, according to Robert Mitchell, director of Theatrical Insights, a box-office monitoring firm, “Marvel titles usually play strongly [in China] and, based on single-character origin titles, Shang-Chi, if released, should have been looking at $100–120 million in China, with the potential to go further.”

At first punch, the film seems tailor-made for Chinese audiences, too. It follows a martial-arts master, Shang-Chi, who has been slumming it in the decadent West as a parking attendant. But when he is attacked by mysterious assassins, he must take up his family’s mantle, travel to China and assume his true destiny as leader of the Ten Rings, a secretive organisation of magical martial-arts experts.

It’s also the first Marvel film to be produced with a largely Asian cast and crew – and, in Simu Liu, a Canadian actor of Chinese heritage, it boasts Marvel’s first Asian superhero. As with Black Panther, which drew enthusiastically on Afrofuturism, Shang-Chi has won praise for its depiction of Chinese legends, cultural traditions and the Chinese-American immigrant experience.

So why hasn’t the film been granted permission to be shown in China? First, blame Marvel’s back-catalogue. The 62-year-old publishing company has produced thousands of comic-book storylines which, like their writers, have buckled and flexed with the times.

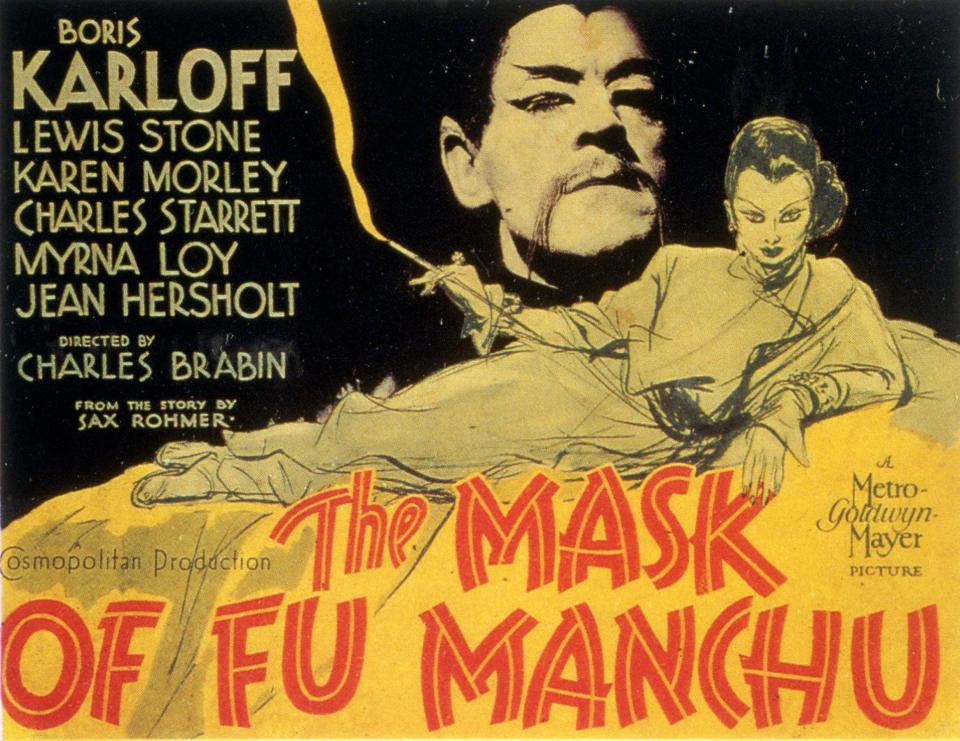

Few, though, are as dated as the series based on Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels. Published between 1913 and 1959, these books drew on pervasive ‘Yellow Peril’ xenophobia, and Rohmer’s prejudices about “Eastern devilry” and the “unemotional cruelty of the Chinese”, to imagine an Asian criminal mastermind who uses sorcery, torture and murderous thugs to conduct a reign of terror. (In one story, Rohmer was inspired by a Ouija board that spelt out C-H-I-N-A-M-A-N when he asked it how to make his fortune.)

In Marvel’s 1970 comic series, Fu-Manchu is Shang-Chi’s father and nemesis. And though the series was cancelled in 1983 over licensing issues, the character would return to cast a shadow over Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.

IKevin Feige, president of Marvel Studios, was forced onto the defensive about the character in an interview for the American premiere: “[Fu Manchu] is not a character we own, or would ever want to own. It was changed in the comics many, many, many years ago. We never had any intention of [having him] in this movie.”

Marvel were also at pains to exorcise the demon of The Mandarin, another Asian arch-villain who caused a buzz of outrage when he made his debut in Iron Man 3. The apparent head of the Ten Rings, The Mandarin was in that film unmasked by Tony Stark as Trevor Slattery, a jobbing actor (played with bemused wit by Ben Kingsley) who had been masquerading as the evil kingpin.

In Shang-Chi, however, Slattery is shown to be jailed by the real Ten Rings – and Marvel’s casting misstep relegated to a joke. When asked why he chose a white man to impersonate him, its leader replies: “He didn’t know my actual name. He invented a new one. He gave me the name of a chicken dish. It worked. America was afraid of an orange.”

Nonetheless, the film’s casting caused other conniptions. A reporter from Asian Boss, a YouTube channel with 1.7 million subscribers, took to the streets to ask Chinese people whether they thought Simu Liu was “too ugly” for the role of Shang-Chi, and whether he fitted Chinese standards of beauty. Many of the people the reporter asked were in agreement that Liu looked “average” or “disappointing”.

Asian Boss describes itself as “a media company with a mission to bridge social and cultural gaps between Asia and the West”. Liu, though, was not on board with this particular piece of cross-cultural journalism, and hit back.

“[I’ve] never been called ugly so many times in my entire life,” he wrote in a Facebook post. “[But] for me, it’s never been about trying to shut the voices out – it’s a fruitless effort (especially if people happen to be making YouTube videos about it). Rather, it’s about learning to let the voices exist and be okay with it.”

He went on to suggest, vis-à-vis Fu-Manchu, that viewers might have more legitimate grounds for concern.

“There are a lot of real and valid reasons why audiences find Shang Chi’s source material to be controversial, and I love the discussion that’s taking place,” Liu wrote. “This… not so much.”

The backlash against Liu came amid the Chinese Communist leadership’s increasingly bad-tempered war against celebrity culture. In China, actors, presenters and singers attract huge followings among young, often digitally-isolated audiences. These fan clubs are loud, unruly and disputatious, sometimes going to extreme lengths to promote their chosen idol.

Last year, for instance, the popular video platform iQiyi was forced to cancel a talent contest when fans brought vast quantities of milk from Mengniu Dairy, a sponsor, to earn points for their chosen heroes – then sloshed it into the sewers.

And earlier this month, a Weibo fan account for the South Korean K-pop band BTS was banned for 60 days after images of a Boeing 737, customised by fans for one member, Jimin, circulated online. According to the state-owned Global Times, the fans had begun saving for the 26-year-old’s birthday celebrations in April, raising 2.3 million yuan (£258,000) in the first hour.

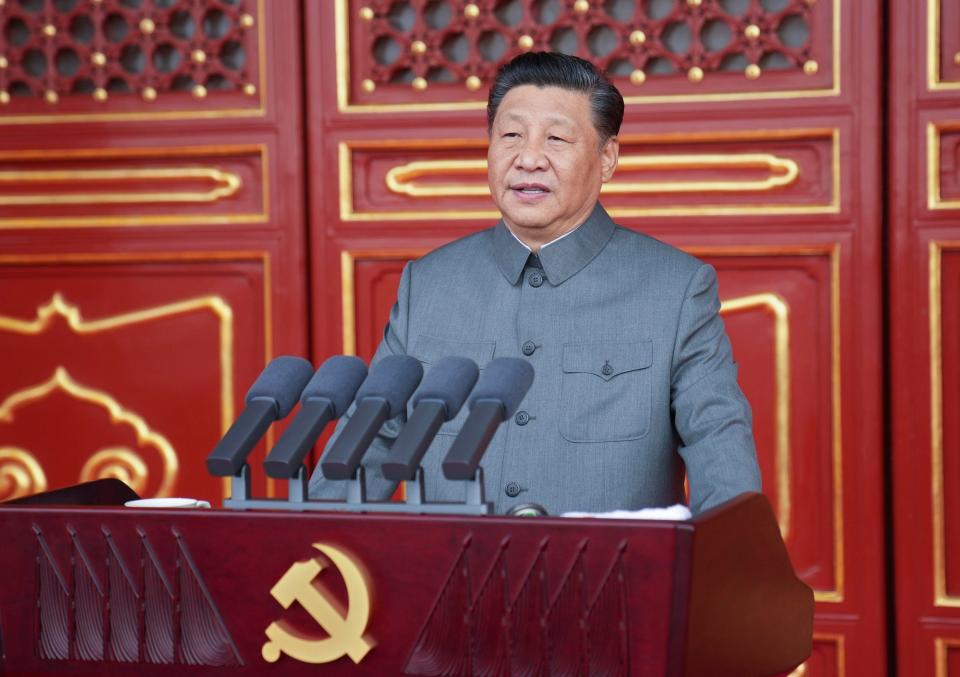

President Xi Jinping has made it clear that he disapproves of this “irrational star-chasing”. He has called for a “national rejuvenation” with greater Party oversight over arts and culture, and further promotion of Communist ideals. As part of this push, the Chinese government has recently banned “effeminate men” on TV and imposed limits on children’s access to video games.

It has also taken aim at the A-listers themselves. One actress, Zheng Shuang, fell out with the authorities over a surrogate baby scandal; she has been accused of tax evasion, and broadcasters have been ordered to stop showing any content in which she appears. Another, Zhao Wei, has been scrubbed from online videos and social media. Thousands of celebrity fan-clubs and entertainment websites have been banned from Weibo.

How this celebrity crackdown will affect Western film studios such as Marvel is, as yet, unclear. But the signs are there: two of Marvel’s next big releases – Spider-Man: No Way Home and Eternals – do not yet have release dates. If, alongside Shang-Chi, they receive no Chinese release, Marvel’s post-Covid comeback faces a gut-punch.

As well as the $100–120 million that Mitchell says he would expect to see Liu’s film take, the previous Spiderman film, Spider-Man: Far From Home (2019), took $205.4 million in China, 18 per cent of its total revenue. (This was par for the course. Avengers: Endgame [2019] earned $629.1 million, 22 per cent of its total, in the country, and became the most successful foreign import of all time.)

Don’t expect a similar reception for Chloé Zhao’s Eternals. Though she was the toast of this year’s Oscars, the director is persona non grata in China after a 2013 interview she gave to Filmmaker magazine was unearthed last year. In it, the Chinese-born filmmaker referred to the country as “a place where there are lies everywhere”.

In addition, the CCP’s censors are unlikely to look fondly on Marvel’s first LGBT kiss between the openly gay superhero Phastos and his husband – a clear example of men being niang pao, a derogatory team meaning “girlie guns”, whose representation on screen the Party has promised to squash.

So will China’s crackdown on celebrities rattle the studio? Mitchell is doubtful. “[Marvel] have a big-picture approach to planning, and they are ultimately too successful around the world. The loss of Chinese revenue makes a potentially huge dent in the box office, but overall their revenue margins remain positive.”

He argues, though, that we may see Hollywood generally tack away from courting China. The CCP imposes a quota of 34 foreign film imports a year, and its revenue-sharing scheme means that studios receive only 24 per cent of the box-office takings.

“There will likely be less direct targeting of China in creative decisions,” Mitchell says. “Studios [will have] to rethink and plan without a Chinese release – seeing one as a bonus, not a guarantee.”

Besides, direct attempts to court Chinese audiences have often flopped. Disney’s Mulan, despite its kow-towing attitude to the CCP and its abuses in Xinjiang, stopped just short of $40 million. Monster Hunter, a dumb, scaly action film based on a popular video-game series, took only $4.7 million on its first day, then was pulled from cinemas because of a perceived racist joke.

In fact, it is often the most overtly American franchises that perform best. The Fast & Furious films are the only imported titles in China’s all-time top 20 that aren’t some form of fantasy – and few would peg Vin Diesel as fitting “Chinese beauty standards”. (On the other hand, his burly masculinity is likely to get the thumbs-up from the Party’s censors.)

For the moment, China still needs Hollywood. Before this summer, its box office stood 21 per cent ahead of its three-year average. Now, after a drought of foreign releases, it is 23 per cent behind. That fall will hurt CCP coffers, no matter how they much they posture against celebrities, fan culture and everything else perceived to be anti-Chinese.

But cinema is now a globally entangled business. A sneeze in Shanghai is heard in LA. So far, only China’s homegrown talent has suffered the ire of the authorities. Could Western stars be next?