Mark Morrisroe, A Pioneer of Queer Punk, Re-Emerges

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

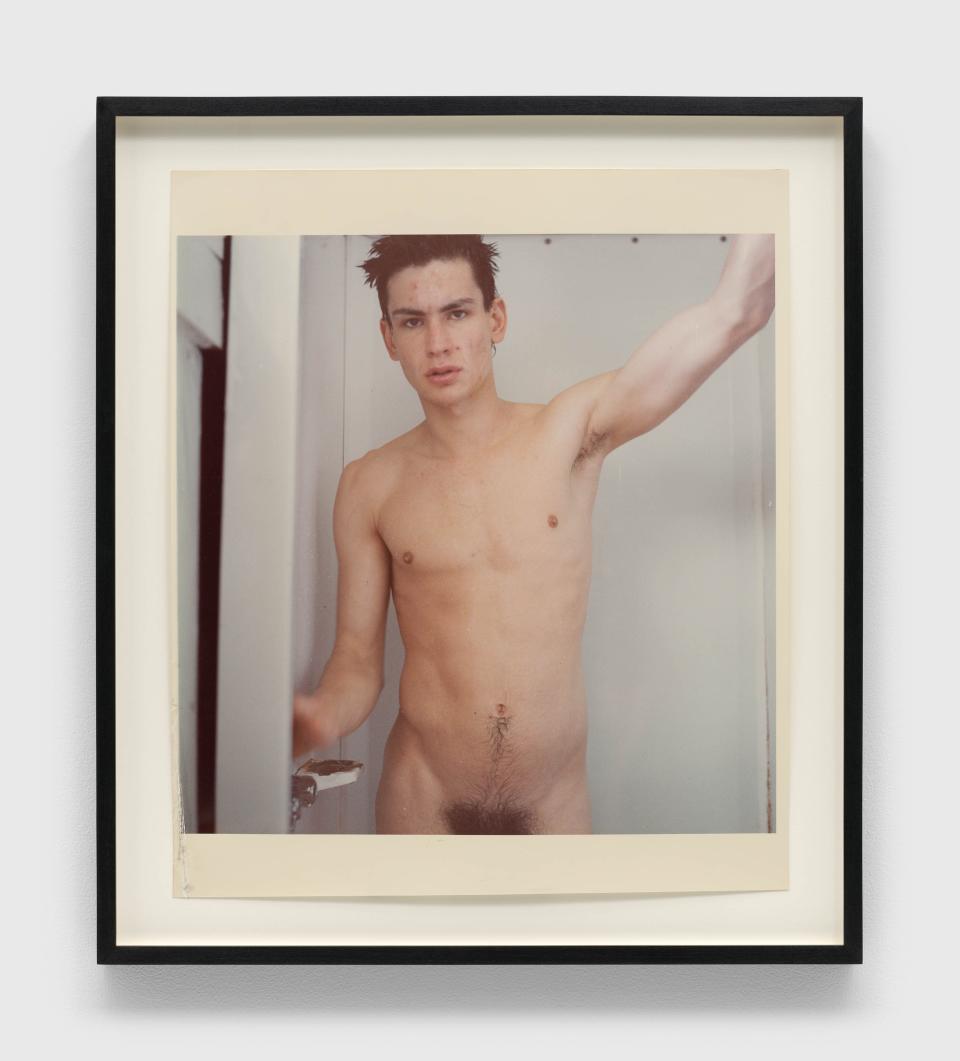

A 22-year-old man confronts the camera from a rusted out shower stall, wearing only spiked hair, acne scars, and an expression that snarls, “What do you want?” Beckoning and hostile, the vibe is Manet’s Olympia meets Sid Vicious. This is a self-portrait of Mark Morrisroe, a queer punk artist whose photography was seminal, influencing two generations of photographers (so far), but whose name more widely is more or less forgotten.

Morrisroe is one of eight artists whose work comprises “More Life,” a program of exhibitions this year across David Zwirner’s networks of galleries that celebrate LGBTQ+ artists lost to AIDS, marking the fortieth anniversary of the discovery of the virus. With a couple of notable exceptions, most of these artists (Marlon Riggs, Frank Murray, Hugh Streets) are for me names that are at once familiar and distant—like people who were seniors when I was a freshman. None are artists that the gallery typically represents.

This weekend is the last chance to see the Morrisroe show, which is up until August 3 at Zwirner’s townhouse (probably better described as a hôtel particulier) on the Upper East Side, the former Richard Feigen Gallery. There, the photographer Ryan McGinley has curated a selection of 25 works that together offer a glimpse into a world of queer life that is (like the names of the artists) both recognizable and foreign. Morrisroe, who died of AIDS in 1989 at the age of 30, was part of the Boston School, whose members also include Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, and Jack Pierson, who was once Morrisroe’s boyfriend. “When I discovered the imagery, it felt so close to home” says McGinley, for whom Morrisroe might be described as a kind of spiritual mentor, though they never knew each other.

Morrisroe’s biography was, and remains, largely mysterious: he was a punk who told people his father had been the Boston Strangler; he was a hustler (strengthening that Olympia comparison) and disabled from an early age, walking with a limp, the story being that a john had shot him in the back when he was tricking. Morrisroe was also a drag queen, and if I could personally own one picture in the show it would be the self-portrait of Sweet Raspberry/Spanish Madonna (1986), which gives all the sultry drama of John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo (1882). “Artists all reinvent themselves through their art,” McGinley says, “but Mark had many characters.”

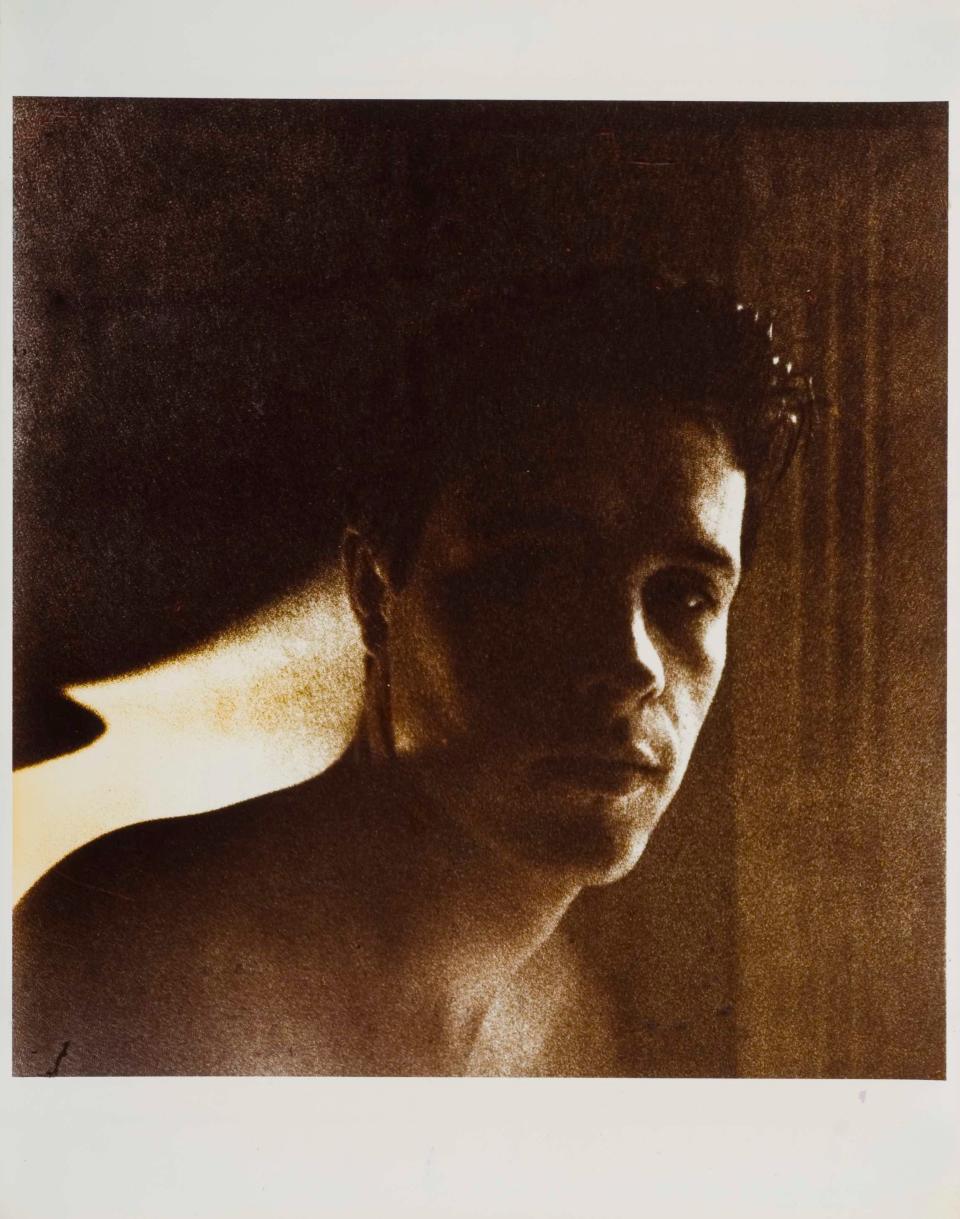

The photographs in this show range from 15 inch square C-prints to polaroids to photogravures, the most interesting pictures reflect an innovative technique Morrisroe called Sandwich Printing. “Jack [Pierson] once explained it to me,” McGinley says. “Mark would photograph in color...print [a picture] in the dark room, then re-photograph it in black-and-white. Then he’d take both negatives and sandwich them together.” The resulting pictures have a kind of dreamscape color palette that makes the viewer not totally sure what they’re looking at—looking at them is like listening to someone with a very strong accent. And that ambiguity resonates with the subjects, many of whom one suspects might have been high when the picture was taken. “His lens on romantic decay is what I love about his work,” McGinley says. “I tried to find stuff that embraced that sensibility.”

Perhaps most important to McGinley was choosing the pictures that would resonate with young people today. He described a lineage of artists that began with Warhol and continued with John Waters, the Boston School, and McGinley himself, and now with young photographers like Awol Erizku, Clifford Price King, and Tyrell Hampton. “[I wanted] to remember a generation of queer artists who didn’t get to realize their full artistic paths,” McGinley says, “to educate people who they were, so they won’t be forgotten.”

Leaving the show, it struck me that had Morrisroe had been born 30 years later, he would probably not have been hustling to survive, that he probably would have survived. I imagined that, if Morrisroe were my age, his circle of artists would have been celebrated as bright young things upon their arrival in New York, with solo shows at Jeffrey Deitch and even an institution like The Drawing Center or ICP. I imagined that Morrisroe might be taking pictures for Vogue. One thing probably would be the same, though: I’d wager that by 2021 Morrisroe would have a show at a global mega-gallery like David Zwirner.

Originally Appeared on Vogue