Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre Looks Back on an Illustrious PR Career

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Did you know that one of the most important developments in the modern history of Chanel — the arrival of designer Karl Lagerfeld on Jan. 1, 1983 — might have happened a decade sooner?

And that the woman who first proposed the German designer to Chanel’s owner in 1973 was a savvy young public relations executive?

More from WWD

That’s just one of the surprising tales recounted by Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre, who last year wrapped up an illustrious 50-year career in Chanel’s communication department, where she put the brand, storytelling and elegance at the top of her agenda.

“I don’t like to say it’s a fashion career. I became a specialist in communications. I prefer to say I communicate about brands,” she relates in a wide-ranging conversation at her Paris apartment, seated in an armchair and wearing a navy Chanel dress accented with a silk foulard, her hair as impeccable as always.

A discreet yet formidable mover and shaker with a vast network of high-level connections, de Clermont-Tonnerre only worked at two fashion houses, Pierre Cardin and Chanel, where she witnessed the birth of ready-to-wear, globalization and the evolution of public relations in a dynamic, yet fickle industry.

The daughter of diplomats, de Clermont-Tonnerre seems to have inherited her parents’ gift for negotiating smoothly around powerful people while pursuing a clear agenda for the brands she served.

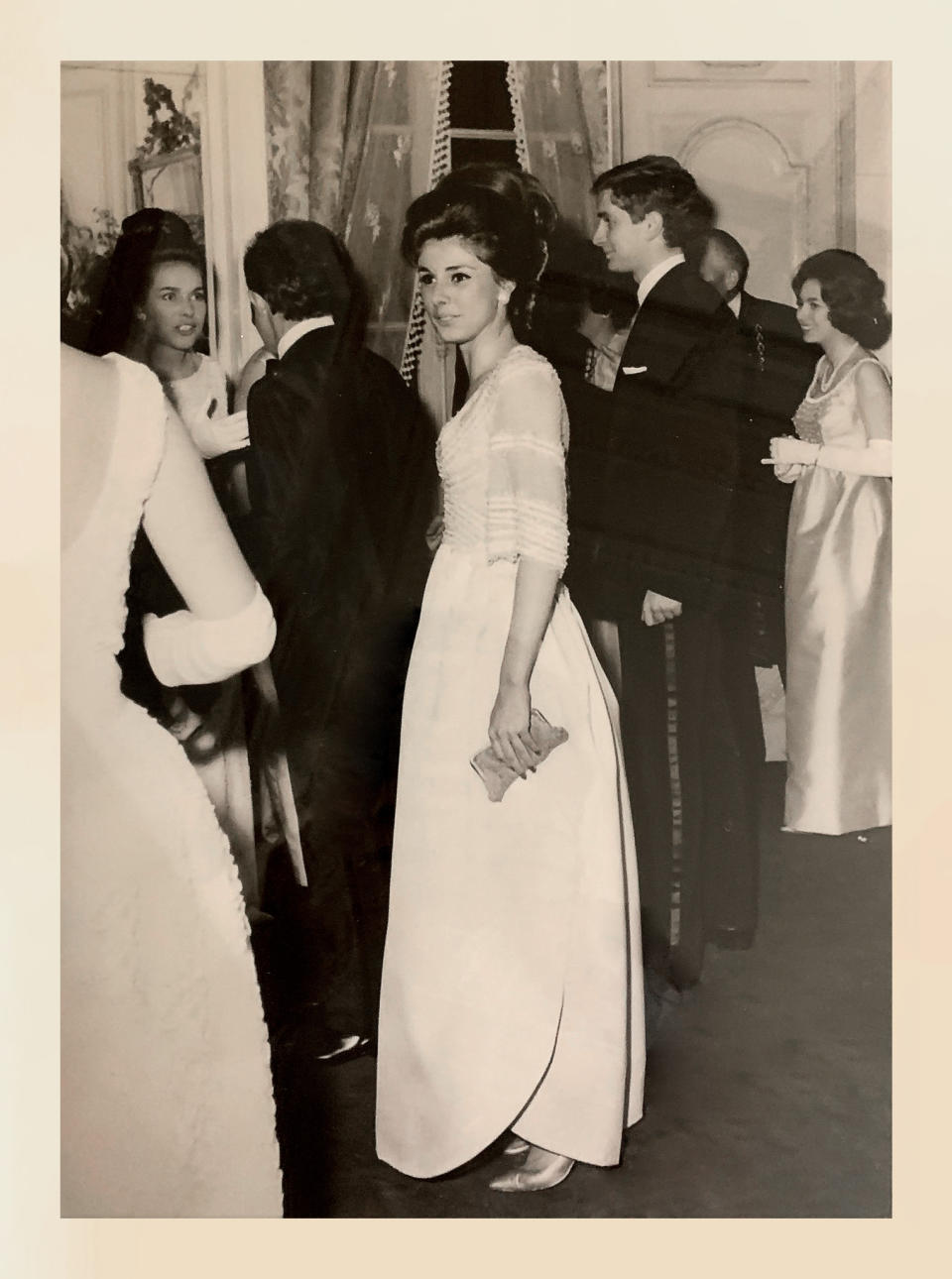

Born in Chile and raised in Paris from the age of 9, de Clermont-Tonnerre was exposed to haute couture as a young girl thanks to her maternal grandmother, who would travel once a year from Santiago for fittings at Balenciaga on Avenue George V. Once she reached adulthood herself, de Clermont-Tonnerre was dressed frequently by a Chilean couturier in Paris named Serge Matta, who moved from Patou to the house of Maggy Rouff, maker of her wedding dress in 1963.

Gerard DELORME/Courtesy of Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre

She said she decided to enter the workforce in order to afford a nanny for her children and in 1966 snagged a job at Pierre Cardin, initially as the designer’s private secretary. Ultimately she became his press officer, learning everything about the metier from Cardin’s formidable couture boss Nicole Alphand, wife of the-then French ambassador to the U.S., Hervé Alphand.

De Clermont-Tonnerre spent four years in the role as Cardin inched into licenses, including a landmark one for colored stockings with Dim. Among her most vivid memories there is Cardin lending her an austere black dress for a funeral, one he had originally designed for his paramour Jeanne Moreau. She doesn’t mince words about his taciturn nature.

On Jan. 10, 1971, Gabrielle Chanel died, and journalists were hounding de Clermont-Tonnerre for reaction from Cardin, who hated Chanel’s clothes, finding them fusty compared to his sleek, Space Age designs. (She fudged and told the press that Cardin was out of town and couldn’t be reached.)

As is turned out, le tout Paris turned out for Chanel’s posthumous couture collection later that month and an executive at the house began searching for a young woman to take over the PR department. Ultimately, de Clermont-Tonnerre was invited by the executive to a dinner at the Ritz, where she was offered the job on the spot, at double her salary.

Cardin was none too pleased when he alighted upon de Clermont-Tonnerre in a tweed Chanel tailleur, grabbing her by the lapels and sniping, “Marie-Louise, you look 10 years older.”

The young communications executive would not disagree. The Chanel couture collections during the first decade of her tenure were at best mediocre, and she wore Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche, Kenzo and Emanuel Ungaro clothes in her off hours. But she relished the challenge, and applauded owner Jacques Wertheimer’s decision to keep Chanel couture going at a time when many houses shuttered after the death of their founders to live off the spoils of perfume.

“I started on April 1. I was told not to wear pants and not to wear miniskirts,” she recalls. “I have to admit it was very difficult to work in this old, ladylike house. Everything was so serious, so strict. It felt like working in a Protestant bank.”

Chanel wasn’t completely off the fashion radar after the founder’s death. WWD’s legendary publisher John B. Fairchild had been very close to Gabrielle Chanel, and de Clermont-Tonnerre was instructed to welcome him and show off the first couture collection handled by Gaston Berthelot and four of the founder’s atelier chiefs. “I was trembling,” she recalls. “He knew everything about Chanel, better than me.”

Of course, Fairchild noticed that nothing had changed at 31 Rue Cambon, and wrote that the house was “like the Kremlin after the death of Stalin.”

Still, de Clermont-Tonnerre did her very best to bring the house and the brand more attention, renewing its membership in the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, which the founder had resisted due to its embargo rules, and inviting a broader swath of journalists from across Europe to attend Chanel’s biannual couture shows.

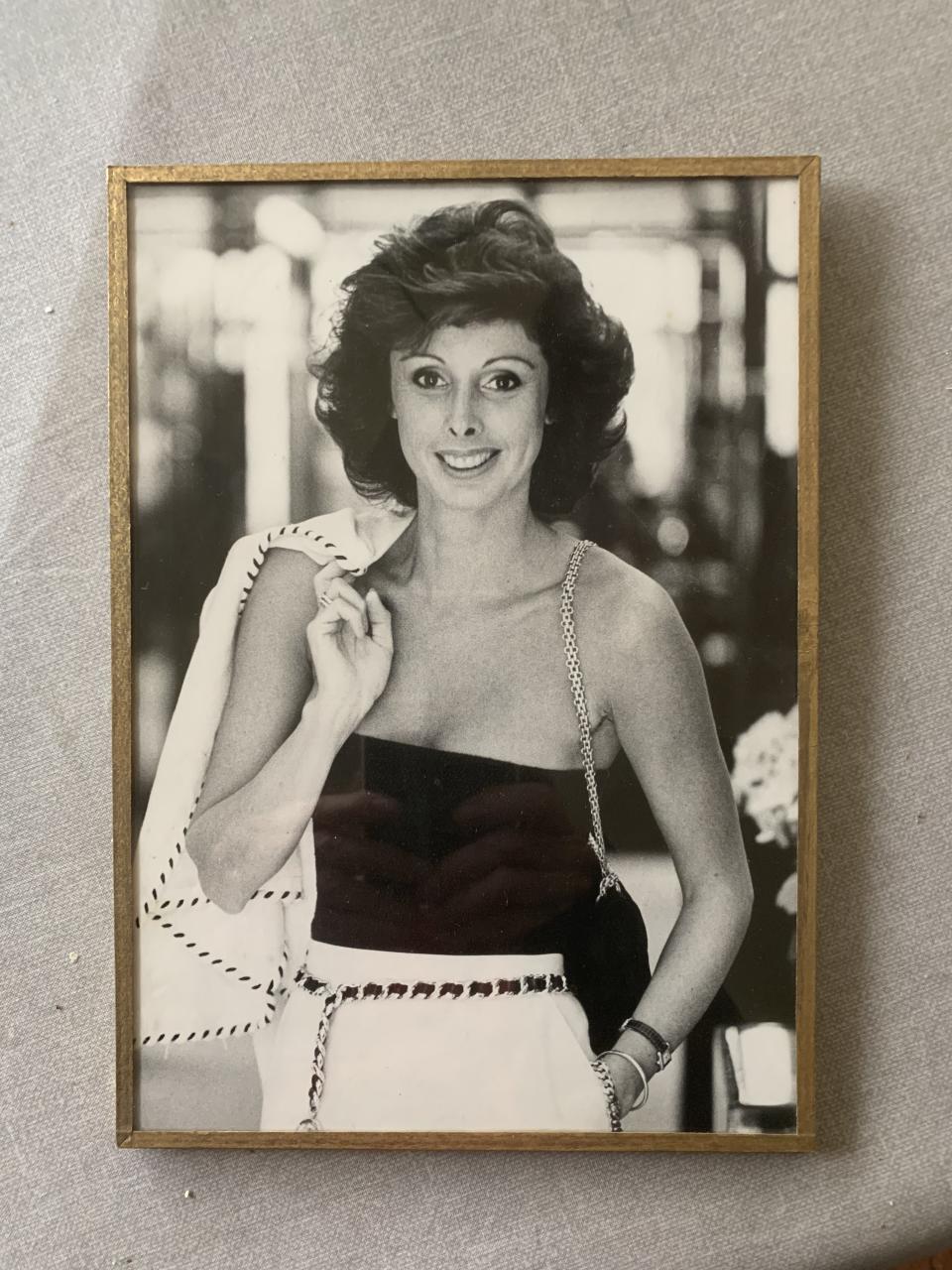

Courtesy of Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre

Given the unremarkable output of the house, the company ultimately tasked Jacques Helleu, artistic director of Chanel perfume, to identify a new couturier. Not knowing much about fashion, Helleu relied on de Clermont-Tonnerre who, after brainstorming, doing some research and consulting with some journalists she trusted, recommended Lagerfeld as the only option.

She didn’t know Lagerfeld personally, but knew his work at Chloé, where he collaborated closely with its feisty founder Gaby Aghion. Figuring Lagerfeld would be best paired with another powerful woman, de Clermont-Tonnerre proposed that he come to Chanel with interior and product designer Andrée Putman, whom Lagerfeld appreciated for her modernity and artistic leanings.

A cocktail gathering was organized for Wertheimer and Helleu to meet Lagerfeld and Putman, only the two Chanel gentlemen never came. “I think they didn’t trust me. Or did they investigate who was Karl in those years? They didn’t like his look? I don’t know,” she shrugs.

Ultimately, Helleu brought on Ramon Esparza, an acolyte of Balenciaga’s, whose first and only collection was “a failure,” according to de Clermont-Tonnerre, noting that many people ran for the door before the show had ended. Two atelier chiefs, known as Monsieur Jean and Madame Yvonne, led by Jacqueline Citroën, secrétaire général of Chanel couture, took over.

De Clermont-Tonnerre found herself idle too much and so she asked the-then president if she could also pitch in on the perfume division, which was about to launch Chanel No. 19 in Europe. Ultimately, she set up a press office for Chanel’s beauty division in Neuilly, collaborating with Helleu on global launches like No. 19, named after the founder’s birthdate, and foreshadowing the storytelling approach that would define her career.

“This was my big chance,” she says, noting she still spent two days a week at the couture house on Rue Cambon. “I did it my diplomatic way.”

It was during this period that de Clermont-Tonnerre began acquiring photos of Gabrielle Chanel and collecting outfits from her old collections, long before vintage became fashionable. “I needed things to communicate,” she explains. “I bought everything that was available! It was easiest for the 1960s, but the most key were the 1930s, but they where quite difficult to find.”

She was also instrumental in the preservation and promotion of emblematic Chanel locations, including the founder’s apartment at 31 Rue Cambon in Paris, ultimately designated a historical monument by the French government.

“I think heritage is important,” she says, switching seamlessly between French and English. “My only spokesperson was Gabrielle Chanel, and I understood from speaking with journalists that she had something.”

About buying photos, vintage clothes and reviving links to the founder’s artistic circles, she confesses: “Very few people understood what I was doing. I was saying, ‘We need to have deep roots to have nice flowers, and you need to water those roots.…That was the beginning of the storytelling in fashion that everyone is doing now.”

In 1978, Chanel decided to launch ready-to-wear with designer Philippe Guibourgé and create a separate organization, giving de Clermont-Tonnerre a third challenge and public relations office. She wasn’t shy about telling management that it was becoming untenable to have three different images for couture, rtw and perfume.

Around this time, Alain Wertheimer, Jacques’ son, tasked his formidable Chanel Americas president Kitty D’Alessio to come up with a proposal for a new designer to rejuvenate the fashion house. Once again, only one name came back: Karl Lagerfeld.

How did de Clermont-Tonnerre feel, given that she had proposed Lagerfeld a decade earlier? “I said, ‘I was right! I was right!'” she says with a laugh.

The negotiations were long as Lagerfeld’s lawyers untangled his various freelance engagements. According to de Clermont-Tonnerre, Lagerfeld ghost designed the Chanel rtw collection presented in October 1982, even though he had put Hervé Léger as his frontman.

De Clermont-Tonnerre is nonplussed when asked if she resented that her suggestion had been ignored a decade earlier. “That’s life,” she shrugs. “It was not love at first sight, but the second sight was the good one.”

Indeed, when she regrouped with Lagerfeld about that missed opportunity in 1973, he told her: “I wasn’t ready, Marie-Louise. I don’t think I would have left Chloé for Chanel in those years. It was too early. When things cannot happen, they don’t happen.'”

In Lagerfeld, she found a like-minded person with sharp instincts about press relations and communications.

“I was very intimidated by this man, but he was so kind and so different from all the other designers I had known, who were so difficult,” she says. “He was very, very nice — so polite, so elegant, so attentive.”

Of course, “he knew everything at Chanel. He didn’t need me. He did his own research. So we could speak, we had a real dialogue,” she enthuses. “Finally, I had someone to speak about fashion. And my training was Karl’s interviews, because he spoke of culture, of music, of books, about everything.…For public relations, it was a dream after the dark tunnel I endured during 10 years. It was fresh air.”

With Lagerfeld installed and rejuvenating the house’s fashion credibility, de Clermont-Tonnerre could better pursue her objective of unifying the image of haute couture, rtw and perfume, exemplified by the 1984 launch of Coco perfume, with Inès de la Fressange fronting that campaign and also the fashion ads, and again in 2004 with a Baz Luhrmann-directed Chanel No. 5 campaign starring Nicole Kidman, who wore a couture gown by Lagerfeld and a necklace from Chanel’s fine jewelry department.

“The three divisions were together,” she says proudly. “For me it was difficult, but it was possible.”

The values de Clermont-Tonnerre pushed in communications and public relations closely echoed Lagerfeld’s, with lightness and elegance at the top of the list.

“It’s elegance, it’s panache. You also need to be focused, and to be passionate about what we are selling,” she says.

De Clermont-Tonnerre confesses that she’s glad to have retired, finding the shallow and often toxic content on social media to be the antithesis of the elegant and cultured storytelling she so treasures.

She also admits to being flummoxed by many of today’s hype brands and fashion trends. “I don’t understand sneakers, I never wore sneakers,” she says with an almost visible shudder.

“When I arrived at Chanel, I liked the refinement: the beige and black shoes, the white cuffs,” she says. “When Karl arrived, I didn’t need to go shopping again because I had everything. The only thing I buy is stockings.”

She leads a visitor to her dressing room, with about half-a-dozen closets lining the walls: one for suits, one for blouses; another for coats, and another for trousers and skirts. It’s a mix of Chanel haute couture and rtw, though de Cleremont-Tonnerre doesn’t disguise her love of the former, relishing the opportunity to wear high fashion suits to Chanel rtw shows.

“I am snobbish. It’s what Karl always said,” she relates, while noting that at couture shows she was always extremely careful never to wear anything a client might have purchased.

From Lagerfeld, she learned to dress in a modern way, in tune with the times. “He told me, ‘Don’t dress ladylike; don’t dress like Ladies Who Lunch,'” she says. “He liked to mix everything together.”

Yet she stresses the need to change and adapt. “It’s very important not to be an old lady, to know how to change, but also to know that at 50 you cannot wear what you wore at 20, and now that I am nearly 80 not to wear what I was wearing at 50. That’s very important.”

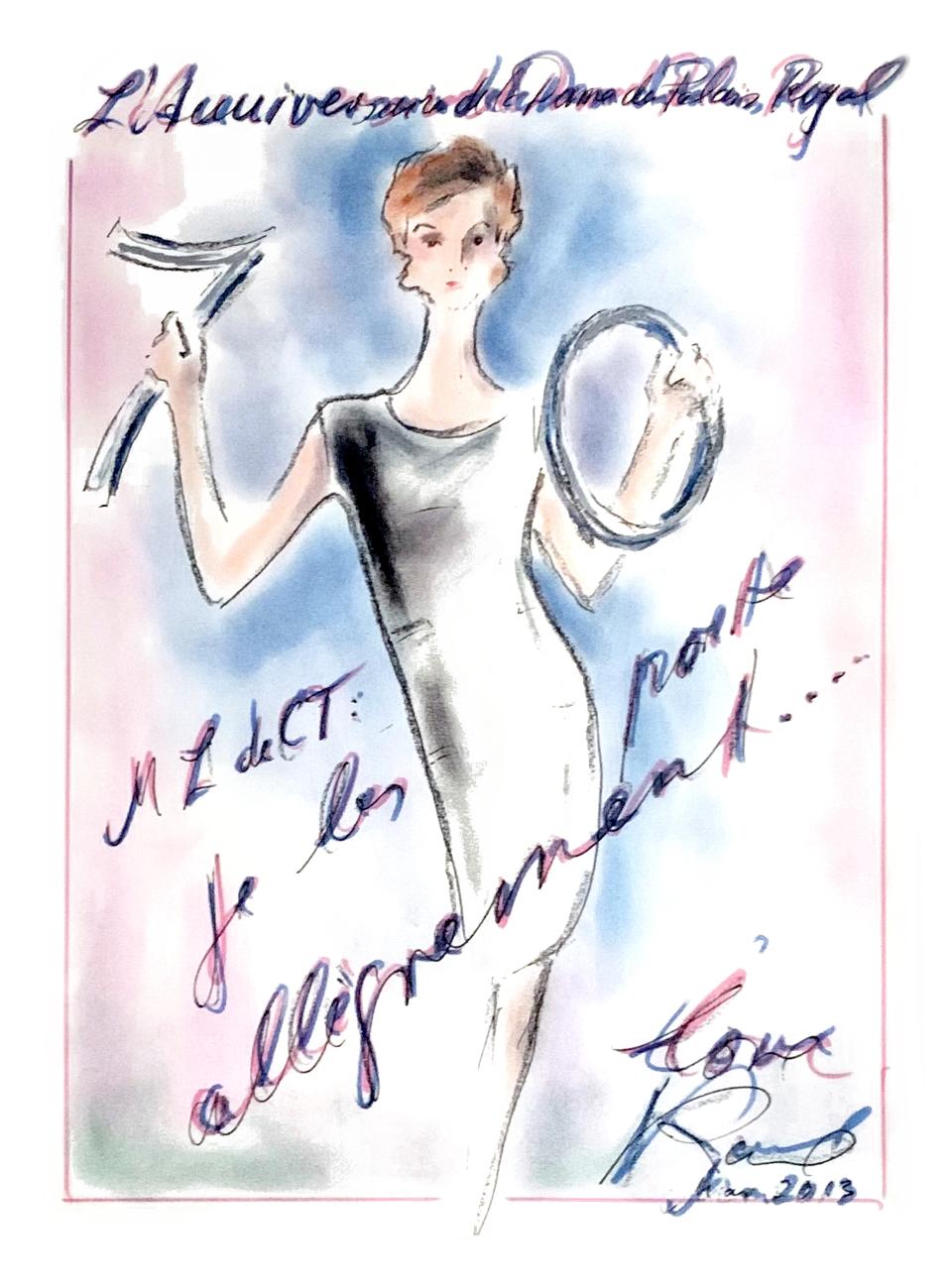

Karl Lagerfeld

Among treasured possessions in her apartment, besides her collection of photos of the Palais-Royal, are hand-colored illustrations Lagerfeld made for each of her big birthdays, one showing her in the Belle Epoque attire she wore for a Proust-themed party; another svelte at 70 in a black-and-white shift dress.

Asked about her retirement pastimes, de Clermont-Tonnerre says she is relishing being able to sleep in, have breakfast in bed and take her time turning to reading, doing yoga, and watching all the movies and series she never had time for during her demanding Chanel years. She’s also enjoying spending more time with her three children and nine grandchildren.

“Having free time is the biggest luxury,” she says, flashing a big smile.

SEE ALSO:

Karl Lagerfeld, Fashion’s Renaissance Man, Dies in Paris

Paris Exhibition Casts Coco Chanel in a New Light

Chanel Handbag Sale Breaks Records at Karl Lagerfeld Estate Auction

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.