Mapping the mixed experience: A celebration of The Blend's first year on HelloGiggles

We started The Blend in July 2017 with the modest intention to give people who claim more than one identity as their own a place to call home on the internet. But in doing so, we unknowingly began to weave a tapestry, or rather a map, comprised of stories that uncover the mixed experience from angles both big and small. Some of these narratives look at the complexities of mothering mixed children, some delve into how ethnic foods (or even tea) can offer an entryway into the mixed soul, and some simply address the ever-present “What are you?” question, in its many different iterations. The Blend’s current map takes you to faraway islands, cultural hideaways (like Japanese grocery store Marukai), large cities like New York and smaller ones like Austin, and places as vast and amorphous as Facebook and Twitter.

Here are select excerpts from the map of our vertical’s first year. We hope you find yourself in these stories, and another space to call your own.

Finding community beyond the “ethnic foods” aisle

Location: Marukai grocery store/Orange County

Growing up in my mostly white neighborhood in suburban Orange County, California, I felt privy to the world’s best-kept secret: I knew of a supermarket with an aisle devoted to packaged ramen, with flavors ranging from spicy miso to heavy garlic. Even better was that this same supermarket sold the fresh ingredients you’d need if you wanted to make ramen from scratch. While my neighbors scavenged the lonely fish section of the local grocery store, my family had our pick of the freshest fish around, sliced gingerly in front of us amid a bustle of shoppers and employees yelling out special deals and catches of the day in Japanese, a market within a market. My family shopped for our groceries at Marukai, a Japanese supermarket located about 30 minutes west of us, and as someone who at the time felt her identity as a half-Japanese person hinged on identifying and consuming Japanese food, I felt entitled to being the only kid in my school who knew of its existence.

For Molly Yeh, farm life and fusion cooking go hand-in-hand—or like scallion pancake in challah

Location: New York City and East Grand Forks

“When I moved to my first apartment in New York, I learned how fulfilling and how cheap it was to make my own food. And I remember calling up my mom for her rugelach recipe and for her Valentine’s Day almond cake recipe. I remember sitting on the floor of the bedroom in my apartment trying to make stiff peaks with a fork because I didn’t have an electric mixer. There were so many things that happened in that tiny kitchen in my apartment that were complete failures, that I would often talk to my mom about or just read about on the internet. There was a lot of trial and error during those years. Beyond that, I worked at a bakery when I moved to Grand Forks, but back when I lived in Brooklyn I would have really big dinner parties just to practice making a lot of food for a lot of people. I basically wanted my entire life to be about food. Everything I read, everything I did was just for the purpose of getting to know food better and learning more about what makes food good.”

Uncovering my queer Latinx identity through literature

Location: The library

A few weeks before my thirteenth birthday, as I hoped for some insight into what I thought would be the amazing beginning of my teen years, I stumbled upon 13: Thirteen Stories That Capture the Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen. I was reading the book only a few feet from my mother by our kitchen table when one surprised me—the protagonist realizes he’s gay after kissing a boy at the movies. I always remembered how that kiss was described, one they’d shared after drinking soda and eating popcorn: a “Coca-Cola kiss.”

That was me, 12, attending a private Catholic school. Every day, I’d sit in class wearing a black-and-blue plaid uniform, listening in on religion classes that often reminded us of our place (as, specifically, young women and young men) in the world. At that point, I’d already gone through after-school chastity lessons where I’d learned that one of the key components of a healthy marriage was “fruitfulness.” This did not connote sexual knowledge; I imagined babies like giant pears in my stomach.

For Jen Hewett, becoming a successful artist of color meant letting go of perfectionism

Location: Blick Art Materials, West Los Angeles

Inside Blick Art Materials in West L.A., Jen Hewett led a block-printing demonstration at a cluster of folding tables. From her new book, Print, Pattern, Sew, she used a pencil to trace one of her design templates, a crocus plant with four blossoming stalks. When she finished, she turned the tracing graphite-side down on a soft rubber block (think an eraser the size of a small greeting card) and rubbed her finger across the top to transfer the image. Then she picked up a carving tool, and after a brief explanation of how to change the blades, hold the tool (the butt end in the center of your palm, your index finger resting across the top), and carve (almost parallel to the block), she started cutting. White bits of block came away in shavings and crumbles. All of us in the small audience watched, and two people said exactly what I was thinking: “You make it look so easy.”

My dad used comedy to assimilate in Japan, and now I use it to make space for myself in America

Location: New York City and Tokyo

My dad worked steadily in film, television, and commercials in Japan. One time, he played Peter Falk’s body double for a whiskey commercial. Another time, he starred in a Pocky commercial that aired non-stop. It helped to be fluent in Japanese (thanks, robot cat) while possessing that classic New York Jew look. He loved being a comedian and actor in Japan. But being a performer was also considered the bottom of Japan’s social pyramid in a very status-conscious society. “Japan idealized white westerners, but white westerners could never truly become part of Japanese society,” he told me.

My mother is Black—but doesn’t want me to be

Location: Arizona and Chicago

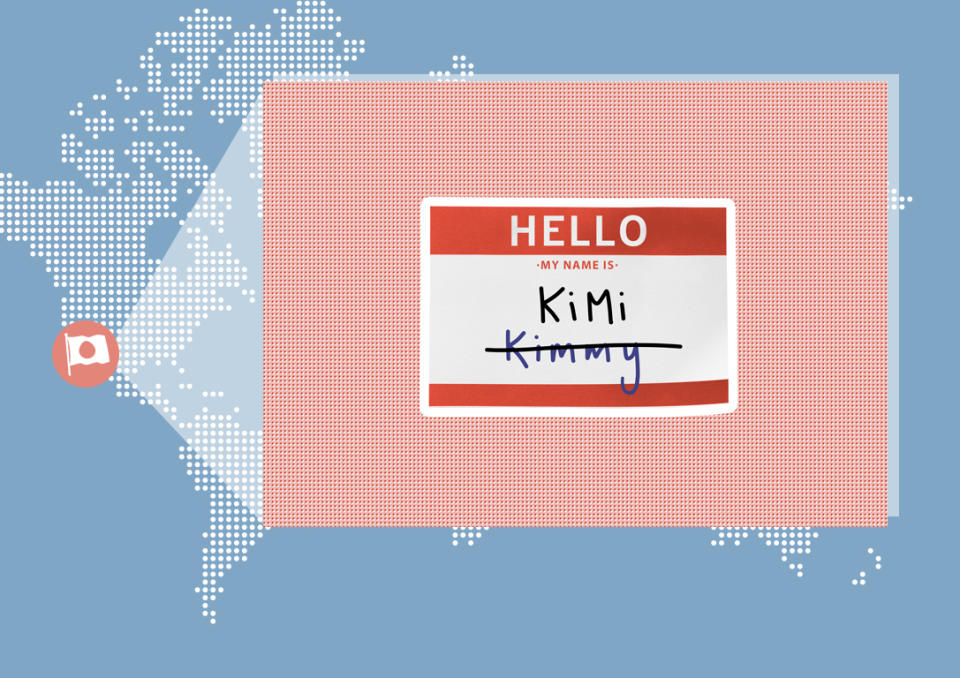

My first step to owning my mixed-race identity was to stop mispronouncing my own name

Location: Japanese American National Museum, Little Tokyo, Los Angeles

The museum literally included me in the exhibit, too: Attendees could have their photos taken, then paste them on the walls of the room at the back of the exhibit space along with their handwritten messages. My portrait is now on a wall in a museum I’d visited as a child to learn more about Japanese American history. I have been weaved, at least for the duration of the summer-long exhibit, into the fabric of an ethnic community in which I have participated but never been fully included.

Janicza Bravo is exposing white mediocrity in her films, using comedy, wit, and #blackgirlmagic

Location: Los Angeles and New York City

Janicza spent most of her childhood in Panama and moved to America as a teenager, right after the L.A. riots in 1992, which she followed on the news. “I remember thinking America was scary,” she told me. She’s adept at illustrating this distinctly American chaos in her work. Gregory Go Boom features mobile homes in a desert landscape and people shooting guns at seagulls for fun. Once she arrived in New York City as a teen, though, her fear quickly dissipated. At 14, she would take the train by herself and go to bars and club parties. “My personality and work…is very much influenced by this kind of toughness I got from that place, a fearlessness,” she said.

Looking for Burma in the perfect cup of tea

Location: Burma

When I think about my grandparents, I think about tea. I think about bubbling pots of rice and curry and that almost completely black—it was so burned—tea kettle punctuating the air with its scream. I think about Sundays, in rooms full of cloudy, yellow light walking over to steaming pots filled with Red Rose Orange Pekoe Black Tea. Black tea that Elsie Koop would fill with cream and lots of sugar. Black tea that John C. Koop would drink by the pot as he sat at the kitchen table either in pleated pants or his longyi, taking bites of dried chili pepper from their garden, while he added tiny notations in statistics journals.

A cup of black tea is the perfect metaphor for my mixedness. It is at once so Asian and so British. It is something, as we know it now, rooted in colonialism. It is as much Downton Abbey as it is Yangon. Loaded with cream and sweetener it is so Burmese and yet something other, something in between.

We took a DNA ancestry test—and the results kind of surprised us

Location: Oshima, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan

My mom’s background isn’t a surprise now—but it was when I found out about it from her brother nine years ago while studying abroad in Japan. I remember sitting next to him at a family dinner when I noticed his light brown eyes and said, “Your eyes are light, just like my mom’s.” I didn’t expect his response at all: He lit up and said, “You know why, right?” like he had a story he couldn’t wait to tell. That’s when he told me that we’re all part Turkish. In the late 1800s, a Turkish ship called the Ertugrul crashed on the shore of the island where my great-great-grandmother lived. Only 69 of the more than 500 passengers survived, and apparently one of them became my biological great-great-grandfather. I’m assuming that’s where most of my “Italian” results come from, unless there are even more family stories I haven’t heard yet.

How men explain my name and face to me

Location: New York City fruit stand

I buy raspberries from a man with a sidewalk produce stand in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood. It’s the middle of the day and I’m the only customer. He wants me to spend more money, time. I ask if he has guavas, fairly certain I’ve seen them tucked away in the corner before. Guava? He explains he’s stocked it before but people in this neighborhood don’t buy it. Try Chinatown, he suggests. I agree and list other rare fruits I know I can find there. He squints and asks if I like guavas. Does he think I’ve never tasted them? Do I not look like I like them? Does he not like them? Or have I reminded him of home?

As a Mexican-Jewish witch, Gabriela Herstik defines identity with magick, fashion, and writing

Location: Los Angeles

Gabriela’s Jewishness and Latinidad are separately important parts of her identity, but I ask if they ever influence her magick practices in small ways. “My spirituality connects me to myself, to my family, to my ancestors—not necessarily because of anything I do, but because of the intention of it,” she said. “I think when I’m doing a ritual, it’s more about honoring the energy of where I come from. I’m honoring the same thing my dad is when he does a Friday night service.” Gabriela also mentions that many of her Jewish ancestors lived in the mountains of Czechoslovakia, and posits that they likely engaged in folk magic and folklore of some kind. She describes including marigold in her rituals, a flower incorporated into altars for Día de los Muertos.

Gabriella Sanchez explores the duality of Mexican American culture through art

Location: Los Angeles

Much of Sanchez’s work centers around the tension of duality, or what she calls “straddling the line”: the line between Chicano and American, personal and universal, the artist and the audience. Sanchez negotiates her place between these two worlds by incorporating disparate elements from one side—sign paintings throughout the downtown area, scenes from family photos, her own signature color palette—with the formal techniques she learned as a Fine Arts major. She prompts the audience to code-switch alongside her, forcing them to think about their own assumptions.

Ezinma mixes hip-hop and classical music to send a bold message about blackness

Location: Beychella/Indio

As most of Bey’s army burst into fiery, marching band-inspired choreography, the string players maintained steady bow strokes and graceful swaying, anchoring the poignant hymn’s emotional core. One of the violinists was Ezinma: situated front-right, she stared boldly ahead as Beyoncé held a long note, thrusting her bow overhead like a torch. She told me earlier that the fact that she played among fellow musicians of color—when she herself did not meet any black string players until age 13—was not lost on her.

When you understand but can’t speak, just eat pupusas

Location: The dinner table

When I was in elementary school, I would spend long summers at home with my grandma while my parents commuted to San Diego and Los Angeles for work, and I was still young enough not to care that my grandma didn’t understand my English. I understood her, though. I must have, because we spent so much time together. I remember two things from that time: Tae Bo videos and eating the authentic Mexican food she cooked for me daily—frijoles, sopa, nopales, burritos on handmade tortillas filled with her fried potatoes. I ate it all without question because it was unquestionably delicious, familiar because it came from my grandma’s hands, and foreign because it was nothing like the square pizzas and canned fruit cocktails I would get for lunch during the school year. When I wasn’t eating, I would flail in our living room watching Tae Bo videos while she sat and watched and laughed.

Questions from two mixed-race daughters about our strong immigrant mothers

Location: Brooklyn, New York

My mom showed me her visa for the first time a week ago. In my mind I had always imagined her emigrating in the fall, and I was right. She arrived October 8th, 1986, less than two months after her 20th birthday. She lived with most of her family (three sisters, three brothers) in a small apartment in Brooklyn, the city in which she would meet my father, the city in which she would have me. She visits Jamaica every few years, and I’ve traveled with her to the country a handful of times. Sometimes to resorts, sometimes to the countryside, sometimes to the small one-level house my grandmother still owns in St. Catherine’s. My grandmother, who usually only spends summers in New York, is now here for an indefinite period. She misses Jamaica. I don’t know if my mom misses living in Jamaica. Maybe she misses the simplicity; maybe she misses the perpetuity of warmth. I really don’t know.

Location: Wakayama Prefecture, Japan

My mom has only gone back to Japan a handful of times, the last time more than a decade ago, when the second of her parents died. Her younger brother lives there still, and when I studied abroad for a year in college, I got to know him, his wife, and my two then-little cousins. My uncle took me to our furusato, our homeland, on the coast of Wakayama, where the cliffs reminded me of those surrounding the beach town my family finally settled in after all those years of moving. He told me that, due to a shipwreck in the early 1900s, our family is part Turkish, making my great-grandmother as mixed as I am, and my mom and uncle’s eyes a light honey brown. I wonder what else I don’t know. I hope my mom and I can go to Japan together, for what will be the first time since I was a toddler. What will she be like there? Will I see a side of her I’ve never seen? Will she feel at home, like a plant in its natural climate?

A letter to the biracial sister I never knew I had

Location: Facebook

My cousin Alyce recently sent me your baby picture, unaware that I didn’t already know of your existence. In the faded Polaroid, which she later sends by mail, you’re staring at your young, blonde mother with my eyes, my widow’s peak, and my long, narrow feet. On the cardboard back is conveniently investigable information—your birth name, birthdate, and address, likely written in your mother’s hand. Our father didn’t think you were his, but you’re one hundred percent mine. It’s a strange feeling to know you’re walking around with half my face, part of my DNA, and no knowledge of your little sister—your biracial double.

As a Black woman and mother, the Austin bombings challenged my mental health as much as my safety

Location: Austin, Texas

Black men and women remain at the intersection of race and violence. There is a lingering silent fear, an ever-increasing anxiety that our movements will be restricted as we are mistaken for an assailant or a target. We are not afforded the deferment of worry that comes with white privilege…My husband, who is white, shared my worries that we or anyone in our majority Black and Latinx neighborhood could be a recipient of a bomb. For me, it went beyond scanning for packages at our doorstep. I checked over my shoulder before I walked in the front door with my daughter. I made sure no one was watching our home or following us when we left. I swallowed my dread every time I opened my garage in the morning. I began to refuse to go outside to walk in the neighborhood and restricted our movements to the house and backyard. I became hyperaware and paranoid. I was often restless.

Joy Wilson, aka “Joy the Baker,” found a path to her authentic self through food blogging, yoga, and writing Drake lyrics on cake

Location: New Orleans by way of Venice, California

“Any cultural sensibility in my food feels more regional to me than racial or of my mixed heritage. That influence could be from my grandmother, who was from the South, and from my aunt, who learned from her, and from living in the South now. So it’s more about this southern culture that I’m learning about that influences some of my cooking more than anything else. It’s a process and it’s nuanced. Southern food is so nuanced, even just in Louisiana, where there is notable difference between Cajun food that comes from the swamps and the Creole food that comes more from the city of New Orleans. I barely understand half of it, but there is a lot of nuance and deviation in flavors that I like to explore in people’s kitchens if I can get into them.”

Twitter and Rashida Jones helped me embrace my Blackness as a biracial person—no, really

Location: Twitter