How Many Women Does It Take to Change a Congress?

The end of 2013 government shutdown started with pizza, wine, and 20-ish frustrated female senators. It was Aaron Sorkin–esque, except zero men were present.

By the first week of October, the partisan battle had dragged Washington to a halt. Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D–N.H.) invited the women to her office to discuss a plan to reopen the government that Senator Susan Collins (R–Maine) had put forth. “There were a lot of people—ahem, men—who would have liked to be the bullies on the playground and just cross their arms and see who had to back down first,” Senator Patty Murray (D–Wash.) recalls. “We didn’t want to wait to see who backed down.” She’s heard that women politicians are more polite and more patient than men, but that wasn’t their motivation: “What we were was impatient.” To finish it. To get back to business.

When the shutdown ended at last, the late Senator John McCain (R–Ariz.) tipped his hat to his female colleagues: “Leadership, I must fully admit, was provided primarily from women in the Senate.”

The Senate comprises 100 members. At the time of the 2013 fracas, its female faction was made up of 16 Democrats and four Republicans. Today the Senate boasts 23 women (only 52 have ever served). It’s a paltry improvement, but leaps and bounds better than the fraction of women in power in other strata of influence: Just six governors are women. Only 24 Fortune 500 companies are women-led—that’s less than 5 percent.

Sen. Shaheen wants to see the Senate look like America, with an equal gender split. (Hers is a moderate stance; when asked at what point there will be enough women on the Supreme Court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg pronounced, “When there are nine.”) But even a modest increase in women could make a difference in how the legislative branch operates and votes and affects all our lives.

The midterm elections will see more women than ever on the ballot. What we don’t know is how many of those candidates will win. If current female incumbents hold their seats, a woman-versus-woman race in Arizona will inch the number of women in the Senate up to 24. Some pollsters think it’s possible that Democratic Representative Jacky Rosen could win in Nevada or Republican Representative Marsha Blackburn could come out ahead in Tennessee, which would push the number to 25 or 26 and create a coalition with far more influence than women have had so far.

With a result like that, we’d be closer than ever to getting the answer to a question that has tantalized and divided political scientists for decades: What would happen to our gridlocked, super-partisan politics if women surpassed the tipping point?

The idea of the tipping point dates back to 1977, when Rosabeth Moss Kanter, then a professor at Yale University and Harvard Law School, theorized the idea of critical mass as it applies to women in positions of power. Kanter observed that women had to make up at least 30 percent of a team to contribute at their full potential. Under that threshold, women were often dismissed as token representatives of their gender—not equal participants, let alone persuasive decision makers. Ever since then, experts have debated the ideal proportion: Is it 35 percent? Would 25 be sufficient? Whatever the number, women in federal government haven’t reached it. “The point is to be included—not seen as an outsider,” says Kanter, now chair and director of Harvard University’s Advanced Leadership Initiative.

Make no mistake, it does help to have one woman, or a handful, in “the room where it happens.” That was visible in April, when Senator Tammy Duckworth (D–Ill.) gave birth to her daughter, Maile. Less than two weeks later she was back in the Senate, Maile in tow, for a vote. But Maile’s presence there—let alone her warm welcome— would have once been inconceivable. Babies have been banned from the floor as far back as all the people who serve in the Senate can remember. When Sen. Duckworth learned she was pregnant, she asked Senator Amy Klobuchar (D–Minn.) to lead a bipartisan effort to strike down the rule. For months Sen. Klobuchar met with colleagues to convince them to support a reversal. Some on the Hill were worried about whether—the horror!—Sen. Duckworth would have to breastfeed. But Sen. Klobuchar made her case, and the rule was overturned with unanimous consent. “I think it would do us good…to see a pacifier next to the antique inkwells on our desks,” said Senator Dick Durbin (D–Ill.) at the time.

It’s a nice sentiment, but it overlooks the fact that the United States remains the lone industrialized nation in the world that doesn’t guarantee paid parental leave. Kanter believes that more elected women would lead to changes in policies like paid leave or access to health care. But Georgetown University professor Michele Swers, Ph.D., is more skeptical. While she acknowledges that women have unique experiences to draw on that can make men view certain political issues with a fresh perspective, she cautions that women are not immune to the extreme partisanship that has infected Washington, despite the notion that women are reputed to be better at collaboration and risk assessment than men. “At the national level, there’s just less room for collaboration than there used to be,” Swers says.

Even so, women in the Senate have tried to make the most of their low numbers. It was former Senator Barbara Mikulski (D–Md.) who set out to boost women’s collective power with routine bipartisan dinners. Credit where credit is due, notes Sen. Murray: “Because we took the time separate from legislative action to know where people come from…then when those impasses are reached, it’s much more likely that someone will reach out and ask, ‘How can we solve this?’ ”

There’s evidence, too, that women in office use their voice to different effect than men. In a 2010 University of Minnesota study, researchers found that women in the House of Representatives give more floor speeches. (How else to be heard in public?) And female politicians tend to emphasize issues that matter more to women and families (never mind that most families include men too): A deep dive into 2018 congressional transcripts found that female representatives spent more than twice as much time on health care in their speeches as male legislators did. Those efforts could have a greater impact, in part, because of the “Jill Robinson effect.” Two political scientists coined the term in 2011, positing that because bias makes it harder for women to get elected, those who do persevere are more adept lawmakers. (The phenomenon is named after baseball icon Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play Major League Baseball.) To wit: The research found that congresswomen claim up to 9 percent more in flexible dollars for their districts than congressmen do. Want to better fund education or health care in your area? Elect women.

While business doesn't do much better than government when it comes to female representation— women make up just 21 percent of corporate board seats in the S&P 1500—active steps have been taken to boost their ranks. California recently passed bills that would require publicly traded companies in that state to have at least one woman on their board by 2020, and more women, depending on a company’s size, by 2022. Europe has had such requirements for a decade. In 2006, for example, Norway established a quota for women on boards. France now has one too; the aim for female representation is 40 percent. The laws were passed in the name of fairness, but they’re also good for business. A 2016 report from global nonprofit Catalyst found that companies with three or more women on their board of directors, no matter the size, outperformed the competition across three crucial metrics: return on equity, return on sales, and return on invested capital. In other words, money, money, money. And research from Miriam Schwartz-Ziv, Ph.D., assistant professor at Michigan State University, has found that members of gender-balanced boards are twice as active (meaning, likely to take initiative) as non-gender- balanced boards.

That math underscores principles that William P. Lauder, executive chairman of the Estée Lauder Companies, says have been baked into the DNA of his family’s business since its inception. In April the company added two more women, Jennifer Hyman, cofounder and CEO of Rent the Runway, and Jennifer Tejada, CEO of PagerDuty, to the board, which means eight of its 17 directors are now women. (For perspective, just three Fortune 500 companies have an equal number of male and female board members.) Lauder chafes at the excuse that there are too few qualified women candidates in the pipeline. Lauder, a member of the 30 Percent Coalition, an initiative to create more diverse corporate boards, maintains women are a “value add” for companies’ boards. Before beginning this latest search, he remembers he was explicit with his current board members: “I said, ‘Here’s what we need—we need expertise in cyber and we need expertise in social and digital.’ On top of that, I said, ‘We need more women directors.’ Those were the criteria: female, with these qualifications.”

Hyman notes that women are responsible for 85 percent of purchases in the U.S., so it just makes sense to empower them in business—who better to know the consumer? She joined Estée Lauder because she trusted her opinion would be valued. “It wasn’t that they hit a number,” she says. “It was that they embraced the diversity of the people who were there across every metric. They say it out loud.”

When Ayanna Pressley became the first black woman ever to serve on the Boston City Council in 2009, she did not feel, from the media and the public at least, the kind of embrace that Hyman describes. What she remembers was the sense that people outside the council believed her success was owed to the idea that voters had wanted to elect a “first.” That narrative, she says, “took away from what I had accomplished.” (After she defeated a 10-term incumbent for the Democratic nomination in September, Pressley is now expected to be elected to Congress in November.) Pressley hoped that chatter would die down in 2013, when Michelle Wu was elected to serve on the council. But both women insist it wasn’t until two more women, Anissa Essaibi George and Andrea Joy Campbell, joined in 2015 (and pushed the 13-person council over the 30 percent mark) that their gender started to matter less.

“There had been a lot of pressure on us to represent this whole spectrum [of womanhood],” Wu says. “Would we line up together? Would we take opposite sides? There was so much examination, solely about our relationship with each other because we are women.” The addition of Essaibi George and Campbell made clear that they serve their own constituencies, not just those who happen to have the same chromosomes. That’s a freedom women in federal government, and Democratic women in particular, lack. When Senator Heidi Heitkamp (D–N.D.) declined to vote for stricter gun restrictions in the wake of the Newtown, Connecticut, shooting, she said in an interview with Time that the backlash from women nationwide surprised her: “A female friend in the Senate said to me, ‘You know, it’s because they feel you represent all women, not just the women of North Dakota.’ ”

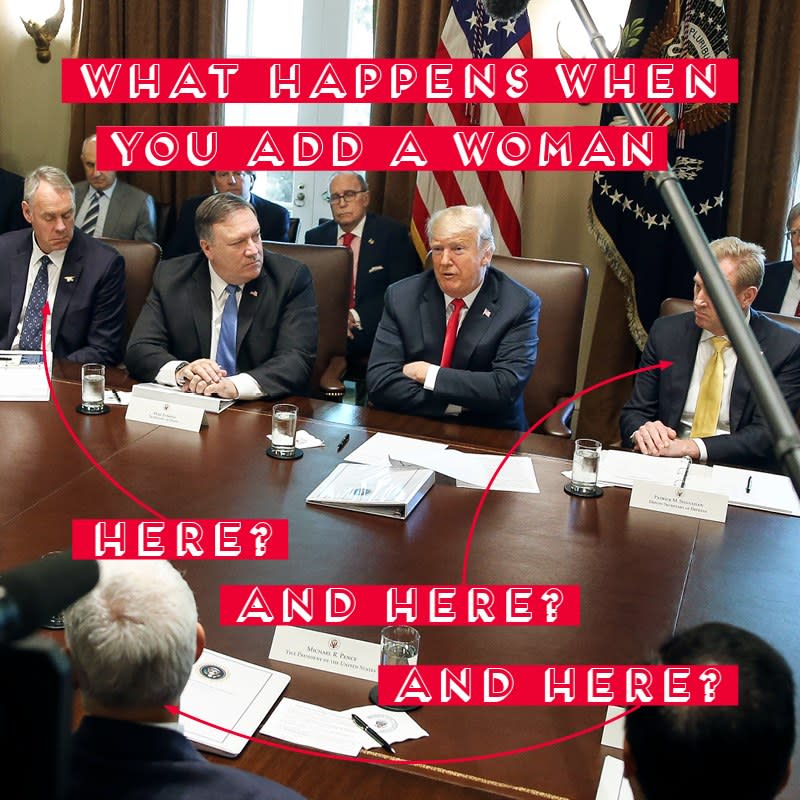

Earlier in 2018, as yet another government shutdown over how and whether to protect the Dreamers loomed, Sen. Collins introduced a compromise bill that would have given the young undocumented immigrants legal status over time and fund border security. Her effort came closer than other prospective fixes, but failed in a 54–45 vote. An overwhelming number of female senators voted for her amendment, 18 in all. (Four opposed, and one wasn’t present.) Sen. Shaheen points out that with six more likeminded women, the bill would have passed. Nine or 10 more, and women would have had a critical mass—and votes to spare.

Perhaps the headline would have read: “Women Save the Dreamers.” But a better result? If people had looked at the numbers and seen that more than 60 senators with different points of view found a path forward. That, explains Ellen Pao, the activist who cofounded the nonprofit Project Include after losing a gender discrimination suit against the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers in 2015, is the real purpose of a critical mass. The more women in power, the less gender has to be discussed. “People need to focus on full representation for all people,” Pao says. “Not just on gender, but on race, sexual orientation, age, and socioeconomic background. We have to keep that goal in mind and realize that 30 percent is nothing, or at least it’s not enough. A threshold is not a destination.”