Manchester Is One of England's Most Dynamic Cities — Here's What to See on Your Next Visit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

From textile town to hotbed of music, Manchester has had a rich — and at times tumultuous — history. Now, the northern English metropolis is establishing a new identity as a global cultural hub.

Emli Bendixen

The Manchester skyline.“Have you been to the John Rylands Library yet?” asked our server at breakfast. “It’s my absolute favorite place in the city.”

My partner and I were eating in a magnificent early-20th-century domed trading hall, now the dining room of Manchester’s Stock Exchange Hotel. We had just emerged from our bedroom — snow-white sheets, pillows piled high as small mountain ranges, sepia photos of the former trading hall in full tilt. (The hotel is co-owned by the former Manchester United soccer star Gary Neville.)

Emli Bendixen

From left: A guest room at the Stock Exchange Hotel; the gardens of the Whitworth Gallery.Since we were fortifying ourselves with a breakfast of Staffordshire oatcakes with mushrooms, a regional delicacy, our server was right to infer that we were preparing for a day of energetic cultural tourism.

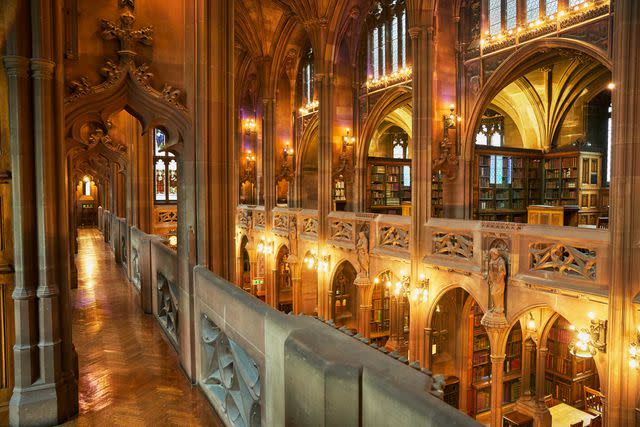

Happily, given the passion with which the words were spoken, my partner and I were able to reassure her. The library had been our first stop on a weekend in this great northern English city that was built on the 19th-century textile trade and is now polishing a well-deserved reputation for culture in all its forms, from football (of course) to music, theater, and the visual arts.

The next big step for Manchester will be the opening of a new venue for MIF: the Factory, named in honor of Manchester’s Factory Records, the label of Joy Division and New Order.

The John Rylands Research Institute & Library was built in 1900 by Enriqueta Rylands, the widow of the industrialist for which it was named, in what was then an overcrowded and slum-ridden part of the city. It’s a neo-Gothic palace of learning, full of literary treasures, including the earliest surviving papyrus fragment of the Gospels, dating from around A.D. 200. An elaborate stone staircase leads to the double-height reading room, where visitors can study under the Art Nouveau light fixtures designed to recall the cotton flowers from which Rylands and this city made their fortune.

When we went, the library was hosting two free exhibitions, one of editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the other about the city’s late-20th-century pop-cultural heritage, including Ian Curtis’s handwritten lyrics for Joy Division’s “Transmission” and early accounts of the Situationist-influenced design for the Haçienda club, which became the center of the dance-music scene in the late 1980s. Somehow, Dante and Curtis seemed like the perfect mix in a city where high art and popular culture gleefully, sometimes chaotically, mingle.

Emli Bendixen

The reading room at the John Rylands Research Institute & Library.In the 19th century, Manchester was one of the wealthiest cities in the world, a fact reflected in an urban landscape that combines Victorian grandeur with vast repurposed former cotton mills and frenetic modern development. The city is still grappling with the fact that the raw cotton that made it rich was grown by enslaved people in the Americas.

In the fascinating Science & Industry Museum, I saw the machines that revolutionized spinning and weaving in northwestern England from the late 18th century onward, but not much, yet, on the human misery on which that revolution was built. It’s a story that will be told more completely in the coming years, when a large-scale renovation of the museum reaches its fruition, the director, Sally MacDonald, told me.

More Trip Ideas: This Luxe U.K. Road Trip Will Take You to English Wine Country, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and 5-star Hotels

The exploitation of labor was also domestic: it’s no coincidence that Friedrich Engels’s 1845 "The Condition of the Working Class in England," with its harrowing descriptions of slum conditions, was written in the city.

Emli Bendixen

The restaurant at the Home arts center.A statue of Engels, who worked for his family’s thread company for two decades, can be seen outside Home, an arts center with a mixed program of performance, visual art, and cinema. This rough concrete tribute to Communist ideals once stood in a village square in eastern Ukraine; it was removed by the villagers in 2015, when Soviet monuments were outlawed. The British artist Phil Collins transported it to Manchester in 2017 — still bearing the colors of the Ukrainian flag with which it had been daubed during protests — as an artwork that speaks powerfully to the issue of who gets commemorated, and where.

At Home, we sampled part of the British Art Show, a quinquennial survey of work from the U.K. Home is one of many cultural institutions that have flourished under a politically stable city government that, since the 1990s, has identified the arts as a means of providing Manchester with economic and social benefit in the postindustrial era.

Dave Moutrey, Home’s director, filled me in on this history over a delicious lunch at Refuge, which is housed in a magnificent 19th-century insurance company office. A devastating IRA bombing of the city center in 1996, he explained, became part of the catalyst for energetic cultural regeneration. Later that year the Bridgewater Hall opened, providing a venue for Manchester’s two excellent symphony orchestras, the Hallé and the BBC Philharmonic. Over the intervening years, many institutions were renewed, not least the Whitworth, a university museum set amid tree-filled gardens that has an impressive collection of historic art and design and also mounts contemporary art exhibitions. (We particularly enjoyed a commission by Suzanne Lacy, an American who filmed residents of a Lancashire town sharing singing traditions in a disused textile mill.)

But it is, perhaps, the biennial Manchester International Festivalthat has become especially important both to the city’s standing internationally and to the aspirations of fellow cultural institutions. Since its founding in 2007, MIF has commissioned work from a range of artists, from Steve McQueen to Punchdrunk and Marina Abramović. Its raison d’être is to put on the kind of work that London wouldn’t, or couldn’t.

Emli Bendixen

From left: Esme Ward, director of the Manchester Museum, in its Living Worlds galleries; a statue of Friedrich Engels brought to the city by artist Phil Collins outside of the Home arts center.Manchester’s cultural leaders are a collaborative bunch: Moutrey and I were lunching with John McGrath, the artistic director of MIF, and Esme Ward, director of the Manchester Museum. She had just shown me around its galleries, which will reopen in February 2023 after a thorough revamp with an exhibition of the museum’s glamorous Egyptian collection.

The next big step for Manchester will be the opening of a new venue for MIF: the Factory, named in honor of Manchester’s Factory Records, the label of Joy Division and New Order. On a hard-hat tour of the site, McGrath showed me the huge, L-shaped space, which will be able to accommodate 5,000 for a standing gig or 1,600 for a theater performance. Opening in time for MIF’s next edition in summer 2023, the Factory will also offer year-round programming, plus bars and an outdoor space leading down to the banks of the river Irwell. No other place in the U.K., he argues, will have anything like this building. It’s all part of making Manchester, he hopes, “a net importer of artists — and a net exporter of arts.”

A version of this story first appeared in the December 2022/ January 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Art and Industry."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.