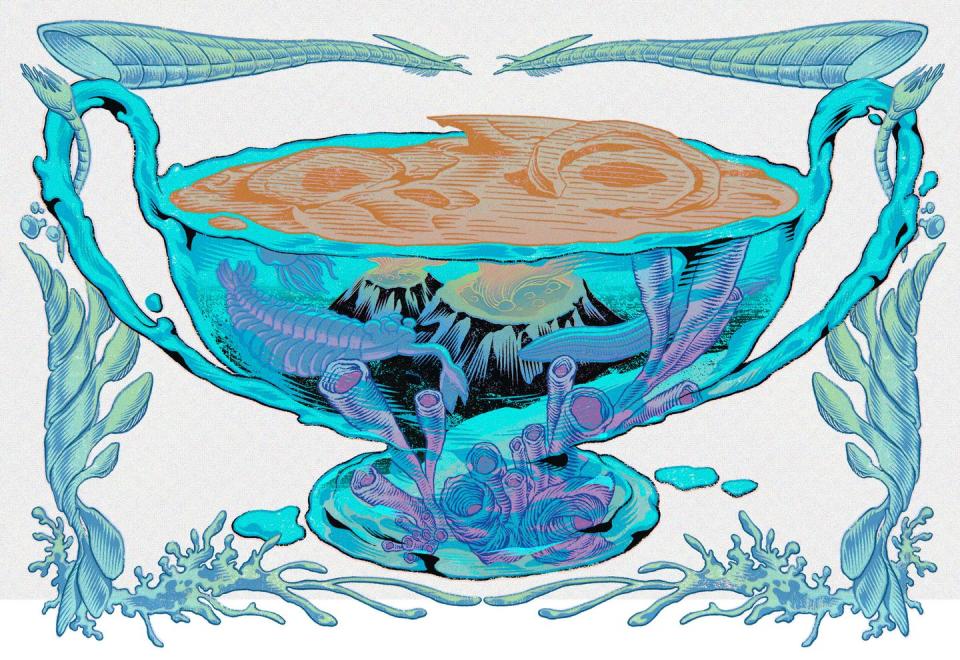

Mammoth Barbacoa, Anyone? Here's How We'd Cook 11 Prehistoric Creatures (And a Few Plants)

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Ever wondered if you could spatchcock a pteranodon? What sauce to pair with slabs of Columbian mammoth steak? No? Just us?

Thanks to advances in paleontology, we now know so much about some of these prehistoric creatures that scientists can almost predict what they might have tasted like. Here at Pop Mech, we relish in the weird, so we’ve created a paleontological menu based on the plants and animals found at three important fossil sites: British Columbia’s Burgess Shale, Utah’s Dinosaur National Monument, and the La Brea Tar Pits in Southern California.

Many of these specimens, with features and traits similar to today’s flora and fauna, represent the earliest in their group’s evolutionary lineage and have helped the scientific community piece together a clearer picture of how life on Earth evolved. Some of these specimens, on the other hand, represent seemingly inconceivable life-forms, lost to evolution with no modern-day analogs.

We asked chefs Sohla El-Waylly, Nik Sharma, and Josh Scherer to prepare a prehistoric meal for our modern-day palates using what we know about these incredible organisms. Their recipes, paraphrased within, are rigorously scientific and wildly creative.

Burgess Shale

British Columbia

The Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies is one of the world’s most valuable fossil sites, containing a massive trove of preserved critters from the Cambrian Period, more than 500 million years ago.

These creatures were likely caught in a series of mudslides, where they were flash-preserved—much like the residents and ephemera of Pompeii—in a much better state than would be otherwise possible, thanks to the layering of minerals that acted as insulation against decomposition. The chemical combination created calcium carbonate, the same hard material many sea creatures’ shells are made of.

In addition to bones, these fossils show soft tissue, giving scientists more to analyze as they study and classify them. Some of the more than 65,000 specimens collected from the site are similar to organisms that exist today, such as sea sponges and worms, which suggests they may represent some of these modern-day animals’ earliest ancestors. Other specimens appear to be unlike any animal alive today, presenting paleontologists with an evolutionary puzzle to solve. There’s still a lot we’ll never know about these animals, but the Burgess Shale opens a window into a period whose creatures could otherwise have been lost to time.—Caroline Delbert

Our Chef: Josh Scherer leads Mythical Kitchen, part of a YouTube network that tests cooking myths, makes high-cost fast food, and has stars like John Boyega and Tom Hanks choose their last meals. He is an award-winning food writer and the author of The Mythical Cookbook and The Culinary Bro-Down Cookbook.

Opabinia regalis

One of the most famous Burgess Shale creatures, Opabinia regalis, is a segmented arthropod with an exoskeleton of chitin and calcium carbonate. (Other arthropods include crustaceans, insects, and spiders.)

Its many segments had fanlike sweepers, creating a skirt like you might find on a hovercraft, and its face was adorned with five beady eyes.

Scherer’s preparation:

There is no better way to cook arthropods than a good old-fashioned Viet-Cajun seafood boil.

Throw shrimp, crawfish, crabs, lobster, whatever you got—including Opabinia regalis—into a big ol’ pot with plenty of butter, garlic, Tony Chachere’s creole seasoning, potatoes, corn, and andouille sausage.

Drink enough Abita beers and you won’t even notice all the freaky eyes. It’s just a butter-suckin’, beer-drinking, nightmare-creature-eating festival of fun.

Choia carteri

Most modern-day animal sponges belong to the class demosponge. We’re used to seeing one kind, the long, porous, and oft-cylindrical “bath sponges,” but many sponges have stems and more developed structures.

Scherer’s preparation:

Since sponges are porous, they’ll likely soak up the flavors they’re cooked in, similar to tofu.

First, we’ll throw Choia carteri into the Instant Pot for about 45 minutes on high, before draining and rinsing to remove impurities. Then we’ll simmer them for another hour or so with thin-sliced pork belly, kimchi, scallion, and gochugaru or Korean chili flakes.

Some “experts” say animal sponges are not edible. I say they just haven’t pressure-cooked ’em long enough.

Gelenoptron tentaculatum

This jellyfish-like critter’s body, made largely from a gelatinous material called mesoglea, is packed within an ultrathin membrane—kind of like a water balloon.

Scherer’s preparation:

I wouldn’t want to disturb that sweet, sweet epithelial layer, but I do want to play with it.

Since this gooey beauty is basically already nature’s dumpling, we’ll wrap it in a thin layer of dough, and then steam it and top it with sour cream, powdered sugar, and lemon zest for a play on the Polish dessert knedle ze śliwkami.

Does Gelenoptron tentaculatum taste like a late-harvest Northern European plum? Probably not, but we’re about to find out!

Pikaia gracilens

This creature looks at first like an eel or fish, but it also has a row of tiny legs, like those on an annelid (segmented worm).

It’s one of the earliest chordates, the large phylum that includes mammals and fish. Its closest living lookalike may be the lancelet, a fish-like invertebrate that lives in shallow waters around the world.

Scherer’s preparation:

Though Pikaia gracilens averaged about two inches in length during adulthood, I would actually harvest my ingredients in their infant stage, when they’re under half an inch.

To start, we’ll gently warm some olive oil with thinly sliced garlic and guindilla chile, and then add the Pikaias to the pan so they can gently warm through.

This recipe calls to mind tinned baby eels—known as angulas in Spain and elvers in England—which are a rare and expensive delicacy that taste awesome spread on some crusty pan gallego. You probably could have made a quick buck selling these 500 million years ago.

Dinosaur National Monument

Utah and Colorado

About 150 million years ago, among the Jurassic floodplains of what’s now eastern Utah and western Colorado, enormous dinosaurs filled a landscape carpeted in ferns and dotted with conifer stands.

Creatures of every size filled the ancient landscape, with a diversity of dinosaur species seldom seen in other times and places. Long-necked, portly giants such as Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Camarasaurus reached their heads high to nibble at ginkgo branches while the spike-tailed, plate-decorated Stegosaurus nibbled at horsetails and other forage closer to the ground. But this place was no herbivorous paradise. Enormous carnivores stalked through the shadows of the woodlands, especially Allosaurus—a 30-foot-long carnivore with triangular horns in front of its eyes and a mouth packed with teeth that evolved to puncture and slice.

The remains of these dinosaurs and many other organisms, including some of our earliest mammalian relatives, were washed into a great fossiliferous slurry that you can now visit at Dinosaur National Monument, along the

Colorado-Utah border. The site is part of the vast Morrison Formation, layers of rock across much of western North America that formed over tens of millions of years. Discovered more than a century ago, the bonebed was such a momentous find that its founder, Earl Douglass, tirelessly petitioned that the site become a living museum. In 1915, his efforts finally paid off as the region officially became recognized as a national monument.—Riley Black

Our Chef: Before becoming a chef and food writer, Nik Sharma worked as a molecular biologist. His 2020 cookbook, The Flavor Equation, explored the roles science plays in the kitchen through 100 essential recipes. His latest book, Veg-Table, illuminates the wondrous versatility of veggies.

Camarasaurus

The long-necked Camarasaurus would have been abundant on the landscape—its bones are among the most common in the Morrison Formation. Even though this stupendous herbivore may have hatched from eggs about the size of a grapefruit, the adults could reach more than 60 feet in length.

Camarasaurus is thought to have fed on horsetails, ginkgoes, and other fibrous plants, “so I’d imagine that the meat would be pretty tough and gamey,” says University of Wisconsin Oshkosh paleontologist Joseph Peterson. A chef would have to find a way to both mask the gaminess and tenderize the meat, not unlike cooks having to cover the swampy flavor that comes with alligator meat.

Sharma’s preparation:

I would try to cook Camarasaurus like lamb. To start, let’s trim some of the fat off and flavor the dinosaur meat strongly with spices and herbs. A lactic-acid marinade—essentially leaving chunks of Camarasaurus in yogurt overnight—would help make the flesh more tender. Then we could try to cook the meat similar to, say, stewed oxtail with yellow or red curry paste. Think of it as a Camarasaurus curry.

Allosaurus

Nearly as abundant as the Camarasaurus, these carnivores were not bone-crushers like the later Tyrannosaurus. Instead, they opened their mouths wide and used their powerful neck muscles to swing their heads like hatchets, their curved teeth puncturing flesh and cutting through to carve off a big gob of meat.

Most adult Allosaurus got to be about 30 feet long, but some exceptional specimens would have stretched about 40 feet from nose to tail.

Sharma’s preparation:

Allosaurus likely would have had low fat content, and would probably need to be cooked more like alligator often is today. I’m thinking…popcorn chicken? First, we’ll marinate the meat in buttermilk before coating it with panko bread crumbs and green chilis. Then we’ll fry it, masala-style, and serve with a tomato chutney sauce.

Stegosaurus

The height of Jurassic fashion was body armor, and no dinosaur wore it so ornately as Stegosaurus.

This herbivore could grow to be more than 29 feet long, its back decorated with alternating rows of polygonal plates and the dinosaur’s tail tipped with four long spikes. Stegosaurus’s neck was embedded with pebbly bones called osteoderms, designed to protect the dinosaur’s throat.

Sharma’s preparation:

Because our human teeth have not evolved to deal with the Stegosaurus’s very strong muscles and ligaments, we’d need to tenderize the meat. So, I’d try to cook it like turkey. Much like the preparation for Camarasaurus, we’ll brine the meat in a yogurt marinade with plenty of spices and herbs overnight. Then we’ll roast it and carve that Stegosaurus up.

Ginkgo, fern, and horsetail

There were no flowering plants in the Jurassic, so many greens we’re familiar with would not have existed yet. In the Morrison Formation, fossils indicate that the landscape was covered in low-growing ferns, with horsetails planted along bodies of water and ancient ginkgo species nestled among the forests.

These plants were relatively calorie-rich and formed the base of an ecosystem that allowed dinosaurs like Camarasaurus to thrive.

Sharma’s preparation:

Planning greens to accompany a dinosaur dish is tricky, as many plant species growing at the time would be toxic if eaten raw.

Plants like ginkgo and horsetail would first have to be boiled in water to help break down the toxins. We could look to recipes like fermented pinecones, a dish popular throughout northern Europe. Many plants have a natural yeast on them, which we could ferment with a sugar syrup to give the plants some flavor.

Alternatively, we could use the Chinese technique of dry-braising, where we’d fry them up, perhaps with ginger, garlic, chili oil, and sherry, to create a crispy side of Jurassic greens that pairs well with any dinosaur protein.

La Brea Tar Pits

Los Angeles, CA

Picture yourself strolling through a juniper-oak woodland. The birds are singing, the sun is shining, and a Columbian mammoth, a relative of modern-day elephants, is trumpeting in panic. It’s 20,000 years ago in what is now Los Angeles, and the mammoth has gotten stuck in a pool of natural asphalt.

Thousands of animals have met their end this way in California’s La Brea Tar Pits, where asphalt—a type of crude oil—is still seeping to the surface. In addition to plant-eaters such as mammoths, a remarkable number of predators such as dire wolves and saber-toothed cats have also been claimed by the tar pits. Predators are rarely found in the fossil record, compared with their prey. The opposite is true at La Brea, where the cries of trapped animals lured hungry meat-eaters to their doom.

The asphalt preserves a fossilized record of life in that region from at least 50,000 years ago through the modern day. Dinosaurs were long gone by the Pleistocene, replaced by a variety of huge mammals. Many of those mammals went extinct as the climate warmed and humans altered the landscape, while others survived and adapted. Scientists can use the La Brea fossils to understand similar changes happening now.—Nala Rogers

Our Chef: Sohla El-Waylly hosts Ancient Recipes with Sohla on the History Channel, where she tests famous historic recipes. (Jesus’s last supper, anyone?) She’s also the author of Start Here, a new science-informed cookbook that teaches fundamental cooking techniques. “When you really know how these cooking techniques work, you can cook anything,” El-Waylly says.

Columbian mammoth

Columbian mammoths fed on grass and other plants and, unlike their woolly cousins, had mostly bald skin. The largest may have weighed up to 20,000 pounds.

At similar sites, archaeologists have found mammoth bones alongside spearheads, and some of the bones have cut marks where the meat was butchered.

El-Waylly’s preparation:

The biggest issue is the size, so I think the best way to cook it would be to make a mammoth barbacoa, a form of barbecue which originated in the Caribbean.

First, we’ll get together and gut it. Next, we’ll dig this giant hole and line it with juniper. (I worked in a Nordic-inspired fine-dining place, so we used a lot of juniper. When you burn it, you get that instant Christmas vibe.) Then we’ll just roll the mammoth into the hole. Mix together some kind of barbacoa marinade, like dried chili puree, maybe some citrus. We’ll pour the marinade on our mammoth, cover it with more juniper, light a fire on top, and let it slow-roast.

People can just dive in and rip off pieces of meat. It’s going to be a party.

Harlan’s ground sloth

In the Pleistocene, several species of giant ground sloth roamed the land. The lumbering Harlan’s ground sloth could weigh as much as a car and had armor made of bony knobs embedded in their skin.

According to U.S. Bureau of Land Management paleontologist Greg McDonald, ground sloths ate plants and were likely lean, with massive tendons that may have made their meat tough.

El-Waylly’s preparation:

Yakitori, a Japanese method for cooking chicken on skewers, might be the best way to go.

First, we’re going to cut that tough connective tissue away, separate out the different muscles, and then skewer them. Next we’ll cook the skewers over coals really fast to prevent them from getting chewy, and then glaze them with a simple tare. (Tare is when you just simmer down soy and stock until it’s really reduced, and it’s got lots of umami and salt.) Brush it on at the end and give the skewers a quick final kiss on the grill. You’d get a lot of char, and it’s a really great way to deal with any kind of tough cut.

Giant short-faced bear

Short-faced bears were among the largest meat-eating mammals that ever lived. When they reared up on their hind legs, they would have been about twice as tall as a full-grown person.

While no one today knows what short-faced bears tasted like, the fat-rich meat from modern bears is full of Trichinella parasites and must be cooked thoroughly.

El-Waylly’s preparation:

Meat-eating animals tend to be more gamey. So, I think we’ll go with a barbecue brisket vibe.

To start, we’ll coat it with a simple salt and pepper brine, and then we’ll smoke it for a really long time so it’ll absorb a lot of that smoky flavor and be thoroughly cooked.

Barbecue comes from the Taino people, so it’s been around almost forever. I think it’s actually possible that Indigenous people could have cooked a bear this way.

Merriam’s teratorn

With a wingspan of up to 13 feet, Merriam’s teratorns were huge birds of prey.

Some scientists believe they ran on the ground and snatched small animals with their beaks, while others think they might have ;fished like ospreys. Yet another theory suggests that teratorns were like vultures, feasting on carrion.

El-Waylly’s preparation:

My go-to strategy for any bird, especially a bird that I’m not very familiar with, is to fry it. First, we’ll break it down into different pieces: wings, legs, thighs, and breast. It sounds like this is a big breast, so I would break it into two parts.

Next, we’ll dry-brine overnight. A dry brine breaks down some of the meat’s proteins into a gel that retains moisture. Finally, we’ll do a traditional Southern, crunchy, Popeyes-style dredge, where you season up the flour and then you pack the flour into every crevice so you get those big crackly pieces.

No matter what this bird is like, it’s going to be delicious.

You Might Also Like