Madras Cloth Unites the World

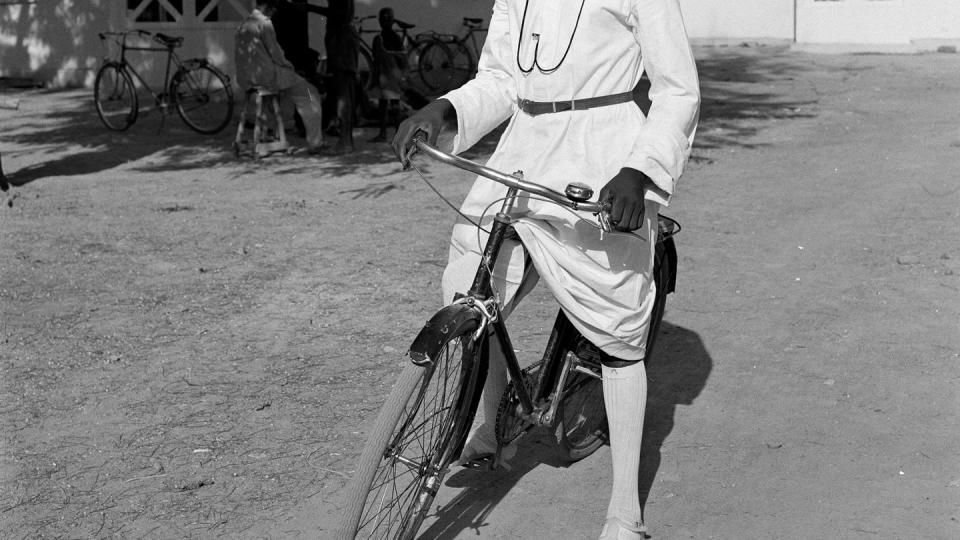

In Bamako, Mali, every sidewalk was a runway. Women styled in bright-patterned pagnes and towering heels. The men, not to be outdone, strutted in embroidered tunics and distressed leather messenger bags. In the year I lived there, Mali’s capital could be many things—hectic and exhausting; gentle and generous—depending on the hour, the traffic, the rains. Always, it was cosmopolitan, fly, très chic.

From this riotous polyphony of fashion, one look stood out to me (and still does): a man in a black mesh top, black leather loafers, and black Givenchy sunglasses. Even without the tailored trousers, it was a bold look, designed to catch the eye and make it linger. But it was the man’s pants—a checkerboard of dark green and black—that made my heart stutter. I knew that pattern, that cloth, those colors. Knew them in my bones.

It was the very same fabric my father used to wrap around his waist in India. He’d change into his lungi the minute he got home from work, its fraying ends brushing his ankles. A sort of skirt-sarong, a lungi granted more breathability and ease of movement than pants or shorts in South India’s humid climate.

Even when I was a child, the cloth was nubby and soft to the touch, worn thin by decades of use. My father had been wearing his since he was a teen—meaning the fabric I saw in Bamako was first produced at least 40 years ago.

Over the years, I’ve wondered how that cloth traveled across 6,000 miles and half a century. Was it a simple story of mass production and global trade? Or was there another narrative playing out, one that united South Asia and West Africa in ways I didn’t yet know?

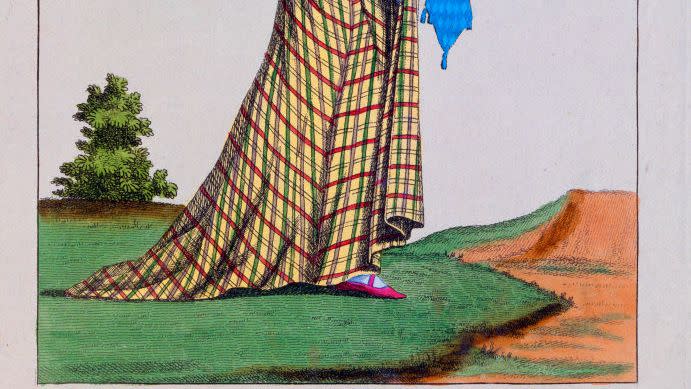

History is a circle, and at some point, it closes in on you. The cloth I saw that day in Bamako turned out to be madras fabric. Named after the coastal city in India now known as Chennai, Madras is where loomers first started spinning the fabric in the 13th century. Madras is also the city where I was born, both of us—person and place—indelibly shaped by colonial rule. In the 17th century, the British East India Company occupied Madras, officially establishing it as a trading port and declaring a monopoly on Indian-made textiles.

Over the next three centuries, the British would trade the fabric across the globe, shipping it to their colonies and other imperial holdings, including French and Spanish settlements in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. The cloth—colorful, breathable, durable—was perfect for the humid climates and hard labor of those who lived under colonial rule. From the Indian peasants and weavers who picked the cotton and wove the cloth, to the millions of Brown and Black laborers and those enslaved who donned it for toiling on fields and plantations and roads across the world, Madras fabric connected colonial subjects across space and time. Their sweat, blood, and the fabric that soaked it all up was immensely profitable for the empire. Scholars estimate the British siphoned approximately $45 trillion from South Asia, with cotton textiles being one of their major exports.

Often, the cloth traveled on the same ships carrying stolen Africans into slavery. Sometimes, it was even used as currency in the slave trade. These are the perversions wrought by empire: a piece of cloth valued as much as a human life; a fabric intended to free Brown bodies, allowing them to move fluidly in hot climates, now used to enslave Black bodies.

Was that what I recognized that day in Bamako—shared histories of subjugation? Did the fabric worn by that man represent a mutual pain of ancestors who’d lived and died under colonialism? Of landscapes and peoples forever marked by empire’s machinery?

The answer is yes—but the answer doesn’t end there. Like any human, fashion is more than the pain it carries. Certainly, the way that guy fashioned his pants—tight, tapered; made for a lush, unhurried sashay—suggested joy more than pain, bold self-expression more than colonial objectification. Fabric has remade the world, and in the right hands—or on the right legs—it can remake a person too.

In fact, the more I’ve learned about madras fabric, the more I’ve understood how the fabric first brought to people by colonization also helped them survive it.

In Nigeria, where the fabric is known as injiri, or “George” (named after Fort St. George, the port in Madras where the cloth was sent to other parts of the world), the cloth is sacred in the Kalabari people’s culture. At a newborn’s naming ceremony, fathers gift their babies uncut madras cloth, marking the child as theirs and initiating them into Kalabari life. The cloth plays an important role in Kalabari death, too, with both the mourners and the newly dead’s house draped in George, a ritual to usher them to the realm of ancestors. Though the British brought the cloth to Nigeria, the Kalabari have reclaimed madras fabric as theirs, imbuing a colonial object of commerce with meanings that transcend empire—that transcend this world even.

Six thousand miles across the North Atlantic, women of the Caribbean have done the same. In response to the plainness and obedience demanded of Afro-descendant peoples by white elites in the region’s Black Laws, Black Caribbean women rebelliously adorned themselves in brightly colored madras headdresses. Patrick Chamoiseau’s novel Texaco, which takes place in pre-abolition Martinique, describes the life-giving importance of these aesthetic gestures: “With necklaces and jewels, ribbons and hats, they were erecting in their soul the little chapels which would at the right time stir up the fervor of their short-lived rebellions.”

Little chapels in the soul. Colonial remnants remade into rebellion. All us descendants of those who’ve survived empire—scattered around the globe but connected by cloth. That’s a type of solidarity white people will never understand. That’s a type of joy empire can’t steal from us.

That hasn’t stopped it from trying. Whiteness is voracious, wanting everything beautiful in the world for itself. As early as the 1930s, the madras shirt found its way to America by way of the wealthy tourists who could afford to vacation in the Caribbean—even in the height of the Great Depression. Just like that, an emblem of Black and Brown struggle became an ornament of white affluence. Today, it can be seen neatly tucked into khaki trousers or styled as an A-line dress on millennials and baby boomers alike.

It feels impossible to reconcile these two narratives of the fabric—one as symbol of resistance to empire and another as empire’s continuation. Why does one feel like reclamation and the other like appropriation?

We live in an era when people who have no inkling of madras fabric’s connection to the British occupation of India, to slavery, or to colonial resistance around the world can buy “genuine madras cloth” on Amazon for $12 a yard. In this reality, it’s hard to keep believing that a piece of cloth holds any real meaning. In a globalized world of mass production, outsourcing, and factory labor, maybe all fashion is appropriative—or none of it is.

The only problem with those arguments? I think they’re bullshit. There’s a reason my heart leapt at seeing that man in his madras trousers—just as there’s a reason my heart sinks when I hear a white woman chanting in Sanskrit or see a white guy in cornrows. Some things feel right, others feel wrong, and if you come from a culture that has been commodified for white audiences for centuries, then you have reason to trust those feelings.

So here’s what I feel: Fashion is material, yes, but it’s also signifier and symbol. Symbols require interpretation; they require a language that both wearer and observer speak. And without speaking, I knew that guy in Bamako, and I shared a language and a lineage. The fabric said it all, and more.

You Might Also Like