I’m 102, stuck in a luxury care home, and bored sick of Vera Lynn

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I don’t want to sing war songs, which is what the entertainers think we want. I don’t want to sit around singing The White Cliffs Of Dover,” says Keith Herdman. “Unfortunately, the entertainers who come in think we’re all old idiots and just want to do that. But I don’t want to do that.”

Keith, who is about to celebrate his 102nd birthday, is in what you might call a rather unusual stage of life. He lives in a very salubrious care home in south London and yet, as someone who is mobile, active and mentally adroit, he is somewhat of an anomaly. The upshot of this is that he is also very bored. So bored, in fact, that he felt moved to write to The Telegraph to explain his plight.

“People spend less time with me because they know I’m OK,” says Keith. “Sometimes I’ll go the whole day and never have a meaningful conversation with anybody. We have an entertainment officer and she does her best – she holds a quiz once a week. There are only three other people who can take an active part in the quiz. That’s very depressing.”

Keith has been in the luxury home for two and a half years – it’s spacious, well-equipped and friendly. His problem is that he is surrounded by others in various states of mental and physical deterioration, which means the system – even the best private care, which this is – will inevitably be geared towards the residents who need constant attention for acute conditions.

“Before coming here I was living in my home county of Northumberland,” says Keith. “My wife Betty died slowly and miserably of dementia in a home up there four years ago and I was alone in a big old house with lots of problems with water leaks and tiles falling off the roof and my son used to motor up from London to see me. And we both thought ‘this is stupid’ and I might as well move down here. This home is as good as any you could find. The trouble is I’m bored out of my mind.”

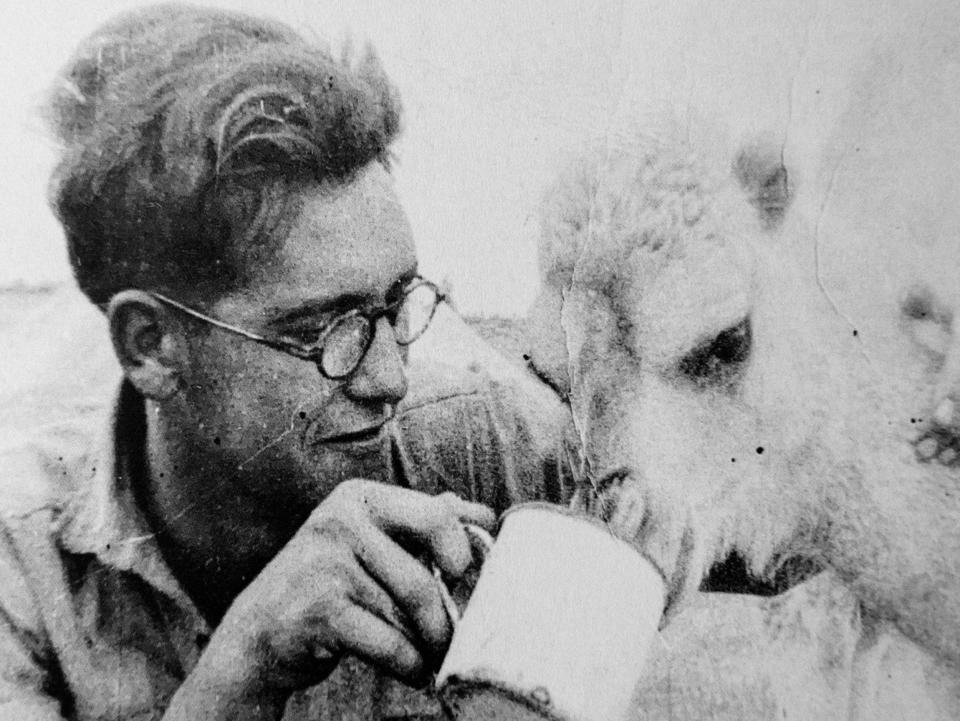

Keith grew up near the village of Wark and began his career as a civil servant with the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance as a basic grade clerical officer in 1938. Working through the ministry office in Newcastle, he rose from that to be Deputy Controller. He married Betty in 1955. “I have achieved my ambition, which was to draw my pension for as long as I worked, and I worked for 42 years.” He was an RAF radio operator in north Africa and Italy during the Second World War and when he opens a wardrobe to show me the medals pinned to a blazer, I recognise them as the same set as my grandfather’s who was in the Tank Regiment.

Keith’s voice is occasionally croaky, but otherwise resonant and clear with the warmest of North East lilts. “I haven’t got dementia and I get very annoyed when the staff talk to me as though I’m a child and I’m not. Most of the staff have got to know me and are prepared for me to be quite rude if they treat me like an idiot. But we have a good laugh. They know what I say can be tongue in cheek. When I get bored I make silly jokes. Most people appreciate them. Some people don’t and my attitude is if you don’t like my silly jokes, then bugger you.”

Looking at the weekly social itinerary, it’s not hard to see what Keith’s problem is. To live in an institution that, quite understandably, must spend the majority of its time and resources on its most vulnerable residents means he is the victim of his own wellness. There are always four planned events each day, often old films and TV documentaries. There is a gardening club, but, thanks to the unusually wet winter and spring, it is a hit-and-miss affair.

“We get a singer here occasionally who sings war songs off-key and dresses as a soldier,” he says, returning to a favourite gripe. “There is a cheapness about the entertainment which I find insulting to be honest. It is not aimed at anybody as chirpy and bright and intelligent as me.” Right on cue I can hear Dame Vera Lynn from a neighbouring room. Again I recall my grandfather, who made a point of telling me how much he couldn’t stand her.

“My alarm goes off at 8 o’clock in the morning, I have a shower and go down for breakfast. I take nine pills. I don’t take part in a lot of the activities because they don’t appeal to me. Then we have lunch and supper and then we go to bed. Sometimes they bring children in from a local school to play board games. I don’t want to do that either.”

Keith sometimes calls the residents “inmates”. His private room is bright and overlooks the garden, and a wall of sunlight falls on the chair opposite his bed. Keith uses plenty of agricultural language, which is a way for him to express his independence and irreverence. “More than half the people in here have their meals in their rooms and are really segregated. It would be easy to feel resentful that I am not getting as much attention as the others.”

So, what should care homes (including one as well-resourced and comfortable as this) do about people like Keith, when so many of their residents are often ill, physically debilitated, suffering from dementia or near death?

“I would like to have an intelligent discussion group once a week,” he says. “Sometimes we have an event called ‘discussion of the daily newspapers’ and you go down to the café and we’ll sit around silently and nobody discusses anything because there aren’t enough residents who can have a discussion.

“I did ask for a belly dancer at a garden party once and they managed to get one, so that was entertaining and everybody got involved. My main hobby is photography and editing my photos on my computer. I do show my best photographs and that’s quite satisfying.”

He says there are three other residents with whom he plays a word game where they take long words and make smaller words from them. One of these was a doctor and he confides that he can always share the dirty words he makes with her. “Some of the people here have been brilliant people and the fact they are here doesn’t mean they’ve suddenly become dumbed down.”

Aside from off-colour jokes and a continuous search for mischief to relieve the boredom, Keith’s time in the home has had more serious repercussions, what he calls a “chastening effect” on his attitude to assisted dying.

“I strongly object to assisted dying being stopped on religious grounds. I am entitled to live how I want to and die the way I want to die. I don’t think anyone else has any right to interfere with my view. But they do. You can decide so many things about your life but you cannot decide when you’re going to die and I think that is wrong. I want to make my own choices. Someone asked me if I believed in an afterlife and I said, ‘I hope not, this one’s been long enough.’”

Keith and his son have agreed to a DNR (do not resuscitate) notice. “The importance of the DNR rule has been exacerbated since I’ve been here because I’ve seen people deteriorating and dying miserably and I don’t want to end up like that,” he says.

“I am bored to tears here but I would be anywhere. I accept that. If anything happens to me and it means I have trouble, then that’s when I want to die. I’m not a miserable old sod who sits around moaning all the time. I don’t want my life to be prolonged unnecessarily and I want to be the person who decides when to end it.”

Apart from four years during the war, this is the first time he’s lived away from Northumberland in his whole, long life. “There are similarities,” he says. “I’ve come to somewhere where I don’t know anyone. I meet people and then they die. It’s just like being in north Africa.

“So, I’ve adopted my old war habits. I go round and I steal anything I can, like biscuits from the cafe and toilet rolls. And I’m always tempted to hide things to annoy people.” Happy birthday, Keith.