“Luxury Was an Emotion”: Neiman Marcus and the Decline of Luxury Americana

Like many morose sybarites before me, my guilty pleasure is looking at photographs of the interior of the Titanic. I know they’re real, but the scale of their luxury is almost impossible to believe. There was a wood-paneled gym with steel columns fancier than any Equinox; gold crown moldings in every first-class room; that giant staircase; hand-tufted rugs and jacquard wall upholstery; and weirdly, 3,000 pounds of garlic bread—on a boat.

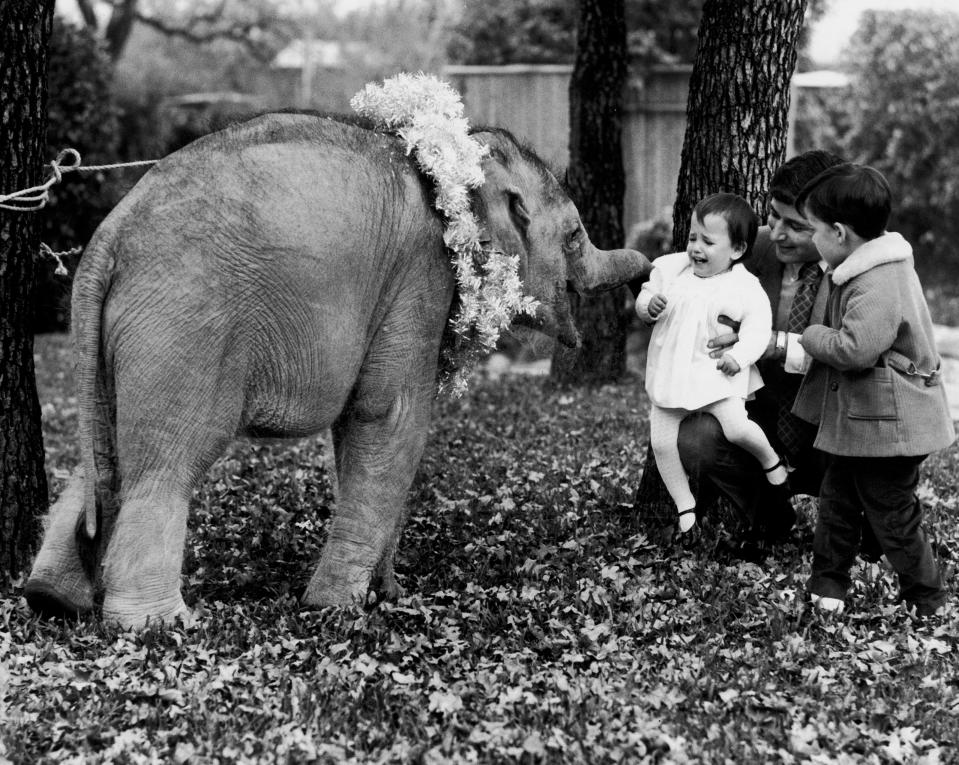

I thought of those images over the last week while reading about the glory days of Neiman Marcus, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Thursday morning. There are photographs of Oscar de la Renta and Emanuel Ungaro, then kings of international fashion, staging shows in its Newport Beach and Beverly Hills stores in the 1990s and 2000s. There is the Christmas book: a bible of “bizarre offerings,” as former president Stanley Marcus described it in his 1974 memoir Minding the Store, that included outrageous ideas like an elephant, and His and Her gifts like Jaguars (a car for him and a coat for her); robes made out of the most expensive fabric in the world (shahtoosh—have a Google!); and submarines—“the ultimate in togetherness.” In 1999, the catalog included a $35 million Boeing Jet. There are photos of Coco Chanel at the Dallas airport embracing Stanley, the son of the founder. Interior images of the store show total splendor—gold, gleaming, thick, where women with red-lacquered talons peddle tweed ladies-who-lunch jackets—that seems too opulent to be true. Like the Titanic photographs, these images seemed somehow difficult to believe—because instead of existing on a boat, they existed in a store in America.

Nothing looks like this anymore. Honey-toned wood and carpeting—not to mention a salesperson who might call you “honey”—have given way to the privileges of glass and efficiency, and a more global sensibility of what luxury means. Many of the most luxurious stores in the world, including those at Hudson Yards, where Neiman Marcus opened its first New York store in 2019, are not unlike international air terminals. They could be anywhere in the world.

The creditors in Thursday’s filing, which will allow the company to restructure and eliminate $4 billion of its $5.1 billion debt, speak to the company’s attempt to adjust to a changing world, including a managing consulting company that specializes in workforce optimization and an affiliate marketing company. But the brands listed as creditors paint a picture of a highly global picture of luxury: Chanel (who is owed about $6 million); Veronica Beard, whose plaid blazers are must-haves for the daughters-who-brunch of ladies-who-lunch ($4.3 million); La Mer, widely considered the Rolls Royce of skincare brands ($3.5 million); and Gucci ($3.1 million). For a store that, during the ‘70s, discovered the Japanese designer Hanae Mori and pushed Emilio Pucci to make clothing out of his far-out scarves, this is a staid image of lavishness. Or perhaps more to the point: this is not the Neiman Marcus that it used to be.

In Dallas, where Neimans was founded in 1907, people talk about the store like people in Boston talk about Harvard or Ohio residents talk about college football—a benevolent hero, a paragon of what the place represents. “More than just being a retail establishment, it was indigenous to the community,” said Ken Downing, who worked at the store for nearly 28 years as senior vice president and fashion director before leaving last year. “Here in Dallas, people are definitely mourning Neimans,” Jane Aldridge, a Dallas native who runs the fashion blog Sea of Shoes, direct-messaged me last week. “Not only because it’s such a part of Dallas’s identity but [because] they employed so many people. Generations of people!”

Search for an answer to what made Neimans so special, and over and over you’ll find odes to its emphasis on customer service over profit. “There is never a good sale for Neiman Marcus unless it’s a good buy for the customer,” Herbert Marcus, one of the three founders, was fond of saying (and his son Stanley was fond of repeating). But in the 20th century, American retail was defined by a handful of retail mavericks with these same values, like John Wanamaker, Marshall Field, and Barneys’ Fred Pressman.

Shoppers at Neiman Marcus in Denver, 2003, examine a $3,500 gold and ruby necklace. Photo By Kathryn Osler/The Denver Post via Getty Images.

But what made Neiman Marcus special wasn’t merely a dedication to the customer. It stood for a uniquely Americana brand of luxury: it turned the department store into a gleaming temple to consumerism. Neiman Marcus made the aspirational feel attainable, often by simply putting it in front of you. Built on the spirit of the west and apocryphal family lore (there’s a nice whopperette about the family starting the store instead of investing in Coca-Cola), Neimans created a mythology of luxury shopping with the panache of retail auteurs, opening a chain of stores across western America where movie stars dropped by for fashion shows and one-of-a-kind runway clothes hung on the sales racks. “Luxury isn’t necessarily a price tag at Neiman Marcus,” Downing rhapsodized. “Luxury is an experience, and luxury was an emotion, far more than how expensive something was or was not.” You didn’t have to buy anything from that crazy Christmas catalogue to feel decadent—just looking at it was rich enough.

The store was something new from the beginning: “There are stories that women would come into the [first] store at Murphy and Elm with no shoes on,” said Downing. “It was truly the wild west at the time.” But it quickly became one of the country’s leading retail successes—while New York was the country’s fashion capital, Dallas showed what Americans would actually buy and wear. And like Gatsby and his unmissable mansion, the Marcus family wanted to tell the fashion establishment that Dallas was not merely a second sibling. “A lot of people thought of the Dallas-Fort Worth area as being a dusty cow town, something built on flash in the pan oil money, something that doesn’t have a lot of history,” explained Annette Becker, the director and curator of the Texas Fashion Collection (TFC) at the University of North Texas, which is now one of the most significant fashion collections in the United States.

During the Depression, the family undertook a series of projects that entrenched the store into the American fashion establishment. As the state of Texas used its 1936 centennial to reinvent itself from a keystone of the post-antebellum south to a gateway to the wild west, Neimans played a key part in “pushing forward a cowboy mentality,” Becker explained: staging a huge fashion show on the state fairgrounds in the midst of the celebrations; launching their Christmas book in 1939; establishing a fashion awards program that was tellingly dubbed “the Oscars of fashion”; and the Fortnight, a multi-day gala that transformed the store with the food, culture, and fashion of then-exotic European countries. Neimans also established the TFC, asserting that the seasonal wares they peddled were in fact museum-worthy collectors’ items.

It embodied a very specific western, try-anything opulence. “Part of what Stanley Marcus, and Neiman Marcus, did from the forties through the seventies, was really try to push forward exciting designs and things that were maybe a little more fashion forward, slightly more avant-garde, than other fashion capitals,” said Becker.

That was the heritage that Downing carried forth. He thought of the Beverly Hills store’s windows as billboards, and the store recruited celebrities—Sylvester Stallone! Paris Hilton! Luther Vandross!—to attend its fashion shows. Neimans’ celebrity savvy reached unparalleled heights. Gingerly, Downing mentioned that there was a certain Alexander McQueen dress, from the designer’s Spring 2003 “Shipwreck” collection, that Debra Messing wore to an awards show. That one, the runway sample, allegedly went to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—but there was just one other made, and it ended up on the racks of Neiman Marcus in Dallas, where it was purchased. (You could just go into Neiman Marcus and buy a McQueen gown!) A few years later, the “music industry” husband of a “very known influencer, fashion person” reached out to that customer to purchase it to wear to an Academy Awards after party. (Kan you keep up with McKueen?) Anyways: “Those are the kinds of dresses that are highly acclaimed editorially, but you rarely see them in a store,” Downing said. Not only could Neimans offer a great cashmere sweater, but also “the super-superlative things, that many people don’t think ever actually enter a store.”

The boys--Sylvester Stallone and Luther Vandross--hit up a Donna Karan show at Neiman Marcus in Beverly Hills, California. Photo by Jim Smeal/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images.

This was all just how Neimans worked. In the ’90s and early 2000s, visiting its stores felt like watching an American remake of a European film, with everything gold and brocaded and sort of vaguely Mediterranean feeling. Just as Barneys epitomized New York cool, Neimans stood for a playful attitude towards the world’s finest things—an egalitarian attitude. As Downing said of the Beverly Hills customer, “They may dress in a casual sense, but they love high fashion, and they interpret high fashion.” That’s the line between shopping on Rodeo in blue jeans with a Chanel jacket, and shopping in sweatpants.

Did Neimans lose its sensibility, or did the definition of luxury itself shift? Neimans is far from the only retailer to find itself crippled with debt over the past decade. Like many retailers, including J. Crew., which also filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this week, Neimans’ troubles began in earnest in 2013, after leveraged buyout left the company with billions in debt. The business was on track for a financial “transformation” before the pandemic, its chief executive Geoffrey Van Raemdonck told the Wall Street Journal on Thursday, “but we had massive interest payments. Covid threw everything off track. This is an opportunity to reset our financial structure.”

But over the past decade, said Aldridge, the Dallas blogger, the store has felt less adventurous. “Ten or 15 years ago the shoe selection at the Northpark Neimans location was better than what they had to offer in New York. They would always have a few really outrageous things, because Dallas has those kooky customers.” Now, she said, “Neimans has become much more conservative with their buying.”

Dallas will never lose its singular sense of style, of course, but the concept of a distinctly American luxury seems to have faded. Or perhaps it’s just shifted to something less about glamour and more about speed. People are still buying kooky, expensive clothes, after all—but they’re finding them online, on sites like Ssense and Moda Operandi. While in-store purchases still make up the majority of luxury shopping around the world, visiting the Hudson Yards store felt like stepping back into a time portal to Beverly Hills in the ’90s, when things like beige and hummus seemed exotic. And each time I went, it was nearly empty.

The Neiman Marcus store at Hudson Yards in New York City. Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Neiman Marcus.

What have we lost, besides great entertainment? “It goes beyond Neiman Marcus,” Becker said, “but there is a certain amount of consumer education that I think used to exist, and used to be cultivated by places like Neimans….They took the time to explain to their customers why spending a little bit more on something would mean that it would last longer or it would be better for their lifestyle.”

A woman at Neiman Marcus in Atlanta in 2003. Photo by mark peterson/Corbis via Getty Images.

Downing said he is hopeful the store will recover, and added that he carries forward the sensibility he honed there in his new role at retail and entertainment conglomerate behind the American Dream Mall, whose opening has been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic but which has already been controversial. “You can’t forget creating an experience, creating an emotion. And that it's not about how people feel when they arrive. How do they feel when they leave?”

What will today’s shoppers, Downing wondered, "feel innately when they hear the name 'American Dream'?" I couldn’t help but think he was talking about the real thing.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified UMB as one of the creditors.

Originally Appeared on GQ