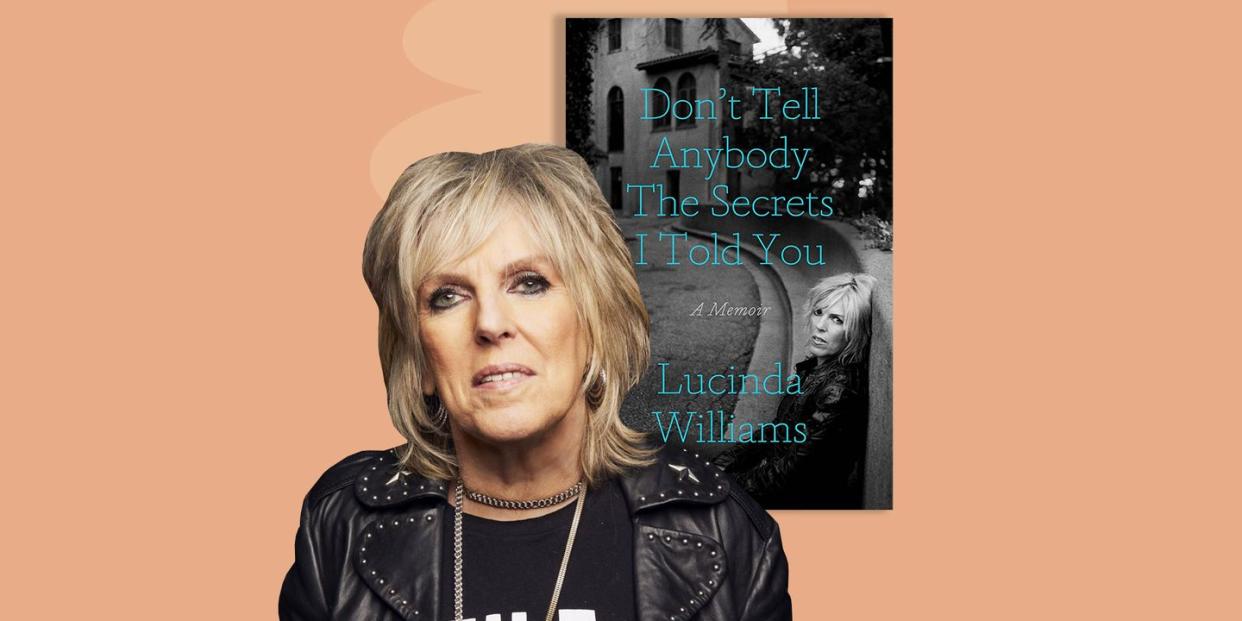

Lucinda Williams Has Another Story to Tell: Her Own

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“At the very beginning of this, I said that I'm gonna be honest,” says Lucinda Williams, resplendent in old-school rocker gear (studded leather jacket over an Aerosmith T-shirt, jeans, and Chuck Taylors) in the lobby of her downtown Manhattan hotel. “It might be gritty, but it's got to be told.”

That was the attitude of a woman once named America’s Best Songwriter by Time magazine as she approached her long-awaited memoir, Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, out now. Like her lyrics, Williams’ prose is plain-spoken, rich with detail, and haunting, as she explores a Southern Gothic story full of wild adventure (it starts with a chronological list of the 23 places she’s resided), creative struggles and triumphs, and romances and near-misses—usually with a type she calls “a poet on a motorcycle.”

Don't Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir

$23.99

amazon.com

Throughout, Williams writes with clarity and empathy about even her toughest experiences, whether describing a harrowing assault by a lover in Memphis’ Peabody Hotel, living with obsessive-compulsive disorder, or examining her life with a troubled, larger-than-life father (the acclaimed poet Miller Williams, who read at Bill Clinton’s Presidential inauguration) and a mother battling mental illness. “Yes, my family was dysfunctional, fucked-up,” she writes. “But that’s not what really matters to me.”

The book—which takes its title from a line in “Metal Firecracker,” a song on her beloved 1998 album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road—is part of a landmark year for Williams. She recently turned 70, last week she started an extensive tour, and in June she’ll release her sixteenth album, Stories from a Rock n' Roll Heart.

This productivity marks her resurgence following what she calls the “apocalyptic” year of 2020, when her current hometown of Nashville was hit by a tornado just days before the pandemic shut down the world. That November, she suffered a stroke that partially impaired some of her motor skills on the left side of her body, forcing her to learn to walk again and taking away her ability to play the guitar. But as soon as she was able, Williams returned to the stage, including a lengthy run opening for Bonnie Raitt.

“She’s been on my wish list for a long time,” said Raitt in a telephone conversation, “and I thought that especially coming out of COVID, especially coming out of her stroke, this was a powerful moment to put two legacy women artists on the same bill. There was a palpable explosion of adoration every night when she walked out on stage and then she just laid it out—I didn't see any diminishing whatsoever; If anything, she just got more burnished and more distilled to the essence of Lucinda. She’s one of our literary, eloquent, soulful, badass artists.”

Williams still moves cautiously but without assistance as she settles onto a couch and sips coffee. She’s candid about her issues with the memoir (even now that it’s done) but is satisfied that she could finally tell the stories behind her life and her songs, like the epic, six-year saga of making Car Wheels—the album that secured her legacy but also earned her the reputation of being difficult to work with. And she’s understandably proud of rebounding from the stroke and re-starting her engine.

“I learned that I actually had a lot in me, a lot of resilience,” she says. “I surprised myself a little bit. A lot of it was just getting back out and doing shows so quickly. At the risk of sounding overly romantic, the music is healing. And everybody's been cheering me on, patting me on the back—I get emails and messages all the time saying, ‘I went to see you at the Bowery Ballroom or wherever, and it made me cry because after all of your ordeal, there you are singing away.’

“Everybody's saying, ‘You're so strong’ and it's kind of embarrassing sometimes. But I earned it.”

ESQUIRE: I have to start by asking how you’re feeling.

LUCINDA WILLIAMS: I'm doing good. I've been doing a lot of rehab. I had to learn to walk again. And I've learned a lot about the brain and how important it is to keep it healthy, otherwise everything breaks down.

At first, I didn't know if I was gonna have to sit down on stage to sing or not, that's been sort of a trial-and-error thing. The first show, they put a chair out for me, just in case. I ended up standing up and singing, which was fine. And I had the back of the chair, because sometimes it's a balance issue. But people have been saying that my voice has been stronger than ever.

You’ve previously come out and said that you didn't actually want to write this book.

I was a little apprehensive because I'd never done it before. I didn't know what to expect. And I didn't know what to do, how to get started. Now I understand the process.

When I'm writing songs, I generally go with the mood I'm in and wait for the muse to hit me. Well, I didn't have the luxury of doing that [with the book], because I've got a publishing company and an editor going, “The book has to be out by such and such, you have a schedule.” I wasn’t used to writing on demand like that, and I didn't enjoy that part of it.

The other problem—or challenge, I like to say "challenge" instead of "problem"—was that I would say something and later want to go back and take it out or fix something, like I would when I was writing a song. I wasn't able to do that; it's done. “We have to put the book out, it's done.” And I'd be like, “No, this part, I have to fix it.” Oh, God. That was hard.

How were you able to let that go?

Because the editor and everybody else would read it and say it was fine. We wouldn't always agree. I do some stuff about my dad within his writing world, and I wasn't trying to be chastising or mean or anything, but I mentioned the writers with their arm candy, because there’s a lot of older writers with young, beautiful girls. Well, that was kind of my dad—my stepmother was a student in his freshman class—but then when it came out on paper…and that's the other thing I learned, it doesn't look the same on paper.

So I told my editor, “I really don't feel comfortable about this. I don't want to hurt her feelings and make her feel bad or she might misread it and I just want to leave that out.” “No, no, it's wonderful, it's great. It describes the literati world” and all of that. We went back and forth and it's still in, so now I'm worried sick about that.

So much of the book comes around to your complicated relationship with this complicated family. Is that always close to the surface for you or did it come out as you were writing?

It's always been a big thing, I'm still looking for the perfect Dr. Freud therapist, which I have yet to find. But one of the things I mention in the book was that, on the one hand, you could say my family was dysfunctional or screwed up, but I didn't want to end up with that picture. So I said, “Actually, my aunt Alexa knew everybody's birthdays and she would send a card every year with one of her handwoven potholders or something, and my grandmother in Baton Rouge taught me what banana pudding was supposed to taste like and how to fertilize the garden with egg shells and coffee grounds, and my stepmom taught me how to set a table with china and nice silverware.” And I went through the family like that, and when you look at it like that, it was a pretty wonderful family.

I didn't know about your OCD. Do you think that relates to the rap that’s always followed you about your perfectionism in the studio? Or is that just called being an artist?

OCD is a real thing. People laugh and joke, “Oh, I've got OCD,” but if you really have it, you know. But you’re right, that was being an artist. But it's also who I am, I guess. I never wanted to use that word “perfectionist” because it has such a negative connotation. And there's always been that weird thing of, why is it a bad thing? Usually in my mind being a perfectionist can mean being rude to other people or making other people think they’re not good enough—“I told you no wire hangers!” and abusiveness or something. That's what people think of perfectionism and I'm not like that. I don't do that.

You've been so prolific in the 21st century that when people talk about your recording anxiety, it must feel like it’s from a lifetime ago.

It just seems trivial and silly, but it does get keep getting brought up. And it's always tied into Car Wheels. One of the greatest things about writing this book is redeeming myself, like, Okay, here's the real story. This is what people didn't know was going on, there was this business part that most people didn't know about—the label folding, I'm looking for another label, then they’re trying to change distribution, so it sits on the shelf. It felt good to be able to finally explain the whole thing.

And to explain some really hard stuff, like writing about the assault in the Peabody—and you name the assailant. Was that cathartic? Or was that hard?

Yeah, that was kind of hard, but I felt the need to do it. I worried a little bit about that, or when I mentioned my mother's alleged—the important word being alleged—sexual abuse. You start second-guessing, maybe I shouldn't say anything, but it's my story. And I've always been a proponent of dealing with stuff that's taboo, to talk about what nobody wants to discuss.

Mental illness is an illness, it's a disease like anything else. I decided, at a certain point way before the book, that I was gonna discuss my mother's struggle with her mental illness openly, in the same way that you might talk about someone having cancer or diabetes. And she was aware of that, and other members of my family knew how I felt, and they felt the same way. It’s always been very open. So in writing about it, I felt like all I was doing was carrying that same thing on.

Did you go into this new album with a particular target?

I think the target was to rock things up a little. I also started collaborating a little bit. That was the big difference this time. My husband and manager Tom [Overby] and I started working together on songs. I was worried about that, but then I thought about Tom Waits and his wife, Kathleen, and that gave me permission to do it. And Tom came up with some good stuff, much to my surprise and delight. I hadn't realized that he had been interested in creative writing before.

So Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart is kind of a mission statement?

Yeah, that’s what I wanted, but I don't know if I succeeded. I've been trying to write a song like Tom Petty for a while now and I don't know if I can do it. God, he was so good. A song like “Room at the Top,” that has so many layers psychologically.

I have so many thoughts about the deceptive simplicity of Tom Petty. I don't think there's a better first line to a song than “She was an American girl/Raised on promises,” which is a novel in eight words.

I want to do that! I want to learn how to do that. I always wanted to write like Bob Dylan, and now I just want to write like Tom Petty. And it's hard for that reason.

But people don't talk about his songs in the same way they talk about Dylan's or Leonard Cohen's.

It's different, maybe because they understand them. They can't believe it's that good if they can understand it. They don't realize that by thinking that, they're insulting themselves.

You Might Also Like