How the Luar Show Became New York Fashion Week's Crowning Finale

On a recent afternoon in Sunset Park’s Industry City, the fashion designer Raul Lopez—whose brand, Luar, is his first name spelled backwards—was in the midst of planning his Fall 2023 collection. In his small office, where he sits with two assistants, paisley fabrics and pinstripes were stuffed neatly onto two clothing racks. The room smelled good, like honey and musk. On the wall behind the desk were pinned a few papers—“Time flies when you’re traumatized,” scribbled on an index card—and a pair of ladylike leather gloves.

A member of his design team walked in— “My children,” Lopez murmured—to discuss a look.

“If we can do the knit with the boulder-shoulder trench….” Lopez trailed off, his eyes growing big with excitement. “Bitch.”

The designer seconded his boss: “It’s gonna look really crazy.”

Lopez sent him on his way: “Make it hot!”

Lopez’s show was 12 days away. Though the collection was still in progress, the atmosphere was tender, familial, relaxed. That was admirable, first because fashion brands—especially when a designer is emerging or independent, and Lopez’s brand, which he launched 2011, is decidedly both—are often rollercoaster enterprises, as anyone who’s seen Unzipped knows.

And second, because Luar is in the limelight. Eyes were already on the designer following his raucous shows in September 2021 and September 2022. His Ana bag, with its enormous round handle, is a bonafide hit that won him the CFDA’s Accessory Designer of the Year award last November. When the CFDA released its calendar for New York Fashion Week’s season earlier this year, the finale, which is typically held by an American eminence like Ralph Lauren, Marc Jacobs, or Tom Ford, was Luar. It felt like the coronation of a new generation.

Where do you start with a collection like this, when your last two shows were highlights of fashion week, you just won a CFDA award, and you’re the grand finale for New York?

“Pressure,” he said, and laughed. Especially because there’s a history to that final show slot, he said. “And now it’s like, me. But I feel like, because I’m from New York and born and raised here, I’m the New York girl. And everyone’s always like, Oh, you’re so New York. Whatever. But now I’m like, Damn. Now I have to go off.”

Lopez’s story is the American fashion dream, one that wasn’t really possible for most of the 20th century and still barely seems possible now. What seems like overnight success with his handbag is in fact the denouement to a decade of burn-out and going broke and reinventing his brand a million times amid outsize influence on other, much larger brands. It’s not that Lopez seems desperate to make it; more that he’s extraordinarily, almost singularly determined to.

Lopez, who is 34, grew up dreaming of fashion and fashioning himself. His maternal grandmother came to the United States from the Dominican Republic in the 1950s, leaving her children with her sister to work in factories in Manhattan and sending money back home. His mother later came to the United States, settling in the South Williamsburg neighborhood Los Sures, where he still lives today. One night, he was watching FashionTV in secret—“I wasn’t allowed to see anything like that,” he said “because I was gay, and it was not cool”—and caught a Christian Lacroix show. “I was like, Whoa, this bitch.”

He started making his clothes and hanging out with New York’s voguing community, where he met Shayne Oliver. He snuck into the library at the Fashion Institute of Technology and poured through books, idolizing the bombastic designers of the 1980s like Christian Lacroix and Claude Montana with their theatrical shows, and scanning or tracing the images to study the designs. By 2006, he and Oliver started Hood By Air, a brand that’s still talked about as ahead of its time and whose designs were closely watched by marquee designers at big European houses. By 2011, Lopez had left and launched his own brand, Luar Zepol, staging renegade shows with his friends modeling his avant-garde clothes. He was picked up by stores like Opening Ceremony, and a few stores in Los Angeles, London, and Japan.

But it was hard to make it work as a business. “Editors were loving it and everything, but I wasn’t making any cash,” he says. Plus the clothes were complicated: “I was like, I’m designing for people tomorrow, today!” He’d made technical pieces that broke down into a bunch of other garments, which is cool, but can be hard to sell. (Remember, even Rick Owens and Comme des Garçons make leggings and leather jackets.)

A hand-to-mouth existence is not uncommon for young designers, especially in America. But, he admitted now, “At that point I was like, I’m trying to make money. But subconsciously I was just trying to get validation from the art and the fashion girls that were my peers that I look up to.” Besides, he didn’t want to make things like T-shirts or hoodies with logos on them. “At HBA, that was our bread and butter: smacking a logo on a T-shirt.” So the cycle continued of scraping together money from the last show to put on the next one. At one point, he decided to stage a huge show at Webster Hall, but then realized he didn’t have the cash to produce anything he’d just shown. “I fucked myself over.”

One important thing clicked into gear at this point, and that was Lopez’s relationship, as a designer, to women. He had been making menswear primarily, but Oliver took him out to a bar and gave him a wakeup call: “He was like, Girl, you need to be Latina. You need to be the new Galliano. You need to take that space.”

Lopez is less a visionary of women’s needs than someone who celebrates the women he knows well. He has an intuitive respect, a kind of awe, for the way women use clothes for power, for confidence, for intimidation. His pieces tend to wrap fabric lovingly around a woman’s body, creating exaggerated shoulders and ruched hips, as in his hero dress for his Spring 2023 collection, which was created in homage to dresses he saw his mother and aunts wearing at family reunions growing up. (In fact, his approach is closer to that of Gianni Versace, with his worshipful sculpted minidresses and suits, than Claude Montana’s cinched waists and impossibly short hem lengths.) His clothes are sexy and commanding, but Lopez designs them out of reverence, rather than a desire to see women embodying his vision.

“I’m not a woman. I don’t know what it’s like,” he said. When he’s designing, he has several people try on the pieces. “I’ll be like, will you wear this? Will you feel comfortable? And if they’re older, what does this remind you of? Is this accurate?” He showed me a video of one of the seamstresses in the factory trying on the Spring 2023 dress. She twirled with glee. “That’s how I create, more than like, I know what a girl wants.”

His first womenswear collection, Spring 2018, showed immediately that this was a strength; without the money for new fabric, he bought dresses at the thrift stores he frequented and reworked them for the runway. (“This one archivist came up to me, trying to kind of shame me. He was like, I heard you go to the thrift store and buy stuff and then just put it on your runway! And I was like…Yeah.” Of course, he spent $30 on the dress, and then had to spend a thousand dollars making the pattern to create a sellable version of the dress. “I’m resourceful,” he said, and laughed. “And that’s sustainable!”)

But in 2019, he basically had a breakdown after more than ten years chasing the dream of fashion success. “I was just like, Okay, I’m broke. [And] it wasn’t that I was broke, it was more like, I need to figure out how to build an actual business, and not just keep making collections to appease the fashion community and editors. I need to make money, and I need to do it the right way.” He went to Palm Heights, a Cayman Islands resort that’s become a clubhouse for the downtown fashion set, and hid out for almost two years, sketching and thinking.

When he came back, a friend heard he was going to do a show in September of 2021. “He was like, You’re gonna go crazy! I was like, Actually, I’m not.” He named the collection “Teteo Basico”— “basic party.”

“How do I reel in the corporate girls?” he remembered thinking. He wanted people to say, “He’s growing. He’s actually designing to build a business.” For the first time, he merchandised his runway: “I dropped the bag, put it on every model. Bring in the sweatsuits, put it on a lot of models. Bring the ties in, put it on all the models.” He studied what brands do to make money, and it was “the shit that I didn’t want to do,” like those logo hoodies and T-shirts and sweatsuits. But once he realized, “I’m comfortable in my skin, I’m comfortable with who I am,” he changed his mind. “I feel like by me feeling good, I can do something that is gonna present to the world [that I’m] good now.”

In June of 2021, as Lopez was planning his big comeback with commercial legs, Kerby Jean-Raymond, of Pyer Moss, reached out to him about a kind of consortium he was launching with Kering called “Your Friends in New York.” The idea was that Kering would provide financial support for designers, primarily nonwhite or queer designers, at Jean-Raymond’s discretion. They offered to help him fund the show— “They were like, We want to uplift you.” He was nervous that he’d feel like he owed them something, but they assured him, “You don’t have to give us anything back,” he recalled. “This is for you.” Kering paid to produce his collection and helped pay his staff. (Lopez is no longer working with the group amid Jean-Raymond’s struggles with his own brand, as New York Magazine reported in earlier this month. Lopez said he hasn’t spoken to Jean-Raymond “in a bit. He’s been off the grid. But I’m really grateful for that whole experience.”)

“Something I think designers need to understand [is that] they can hop off the wheel,” he said. “You can take a break. It’s not that serious.” Designers assume that if they don’t show one season, everyone forgets about them. “You’re so hard on yourself because you’re like, I can’t let everyone down. I’m trying to create a space for my community and all my friends so everybody can see we can do this. And I didn’t wanna let everyone down, in a weird way.”

Lopez’s September 2021 show, with sexy crocodile trench coats, suave tracksuits, and logo ties, proved that a few seasons off will hardly alienate your community. Guests were so eager to cram in to see his comeback show in the garage of a Bushwick warehouse that they sat on each other’s laps. When the first look came down the runway, almost everybody screamed. And then they didn’t stop, yelling at look after look: Yes bitch! I know she’s that girl!

On the arm of every model was a bag he called the Ana. The idea started with the women in his life. “For me it was like, [my grandmother] gave to [my mother], [my mother] gave to me. How do I give back to both of them?”

The mod handle is a tribute to his grandmother’s time working in the city in the 1950s, and is inspired by shapes he came across researching fashion in the library. “I’m a library girl. Once it gets on Instagram and Tumblr and all that—it’s regurgitated 800,000 million times.”

“And then the briefcase shape was an homage to my mom in the eighties and nineties,” he continued. “Everyone had a briefcase. My dad wore a briefcase everywhere. We lived in the hood, and [he’s got a briefcase]. I love that. It was what they thought American luxury was.”

After the show, he launched a preorder on his site, which sold out within 15 minutes. “It was crazy.” His friend Telfar Clemens, whom Lopez calls “my sister,” reached out and said, “Bitch, we’re going to dinner.” They popped a bottle of champagne and Clemens christened him “the accessories girl.” The bags, which sell for $265 for a mini version to $395 for one that would fit a laptop, were picked up by Bergdorf Goodman, who asked Lopez to make an exclusive for them in an embossed crocodile, as well as Nordstrom and Moda Operandi. Dua Lipa and Julia Fox were seen carrying it.

“I wanted to make something where it can be an heirloom, where it can be like a Vuitton bag or a Gucci bag, and you can hand it down from generation to generation,” Lopez said. That thinking is the driving force behind the collection he’ll show next week: pieces that are heirlooms in the world in which he was raised. “I’m Latino, so growing up for us in the hood it was like, you made it when you had the fur. You know? And that gets handed down.” For others it could be a jacket or a pair of Jordans. “In a white family, my friends get the diamond ring that was their great-grandmothers, and it’s handed down from generations, which is beautiful. And for us it was a different thing, you know?”

He thinks a lot about what objects and experiences he grew up with, and how he can pay tribute to them through clothes. “A lot of us grew up in these urban dystopias and all these like, you know, shitty habitats. But I like to trigger these specific moments that we all cherish and understand. And even my friends that don’t come from these neighborhoods get it because they were around it and they saw it all.”

Fall 2023 is called Calle Pero Elegante, he said, “which means streets, but elegant. I just wanted to shine light on these, per se gangsters, but they’re not really gangsters. They were just women who were hustling to make money for their families. And you know, in these neighborhoods, we will say, Oh, that’s so gangsta.” Which is to say: “These women who, when they walked in these spaces, commanded respect, and attention, and people looked at them because of the way they dressed and because of the way they carried themselves. As this young POC kid, seeing these boss-ass women was kind of like, Whoa. Men are bowing down to them. My mom always said, ‘The man could be the head of the house, but I’m the neck. I’m moving [him] wherever I want.’ And it’s that mentality—to me, that’s gangsta. These figures who do what they have to do to provide for the next generations coming, and maybe their kids or friends or whoever—they’re helping create generational wealth through a newfound path that wasn’t given to them. They had to earn it.”

Clearly, the bag is sustaining Lopez’s budding empire, though he continues to do consulting work for fashion brands on the side, and does not take a salary from Luar. He doesn’t know how many of the bags he’s sold: “I could have an idea, but I choose not to.” He wants to know the bills are paid, the employees are being paid, the factories are paid, cash is flowing, clothing is selling. “I don’t want to make myself crazy, [thinking] we should be selling more.”

“That’s another key thing with young designers. Sometimes it’s just like, you dibble and dabble into the cash, and that’s when you kind of fuck up, you know? You shouldn’t touch it. That’s another reason why I kind of don’t [look at sales numbers].” The brand’s revenue “keeps the Luar world afloat. And I keep Raul afloat.” Flying back to the Dominican Republic or posting up at Palm Heights—“that’s not coming from the Luar coin, honey. That’s me on the side doing my little consulting gigs.”

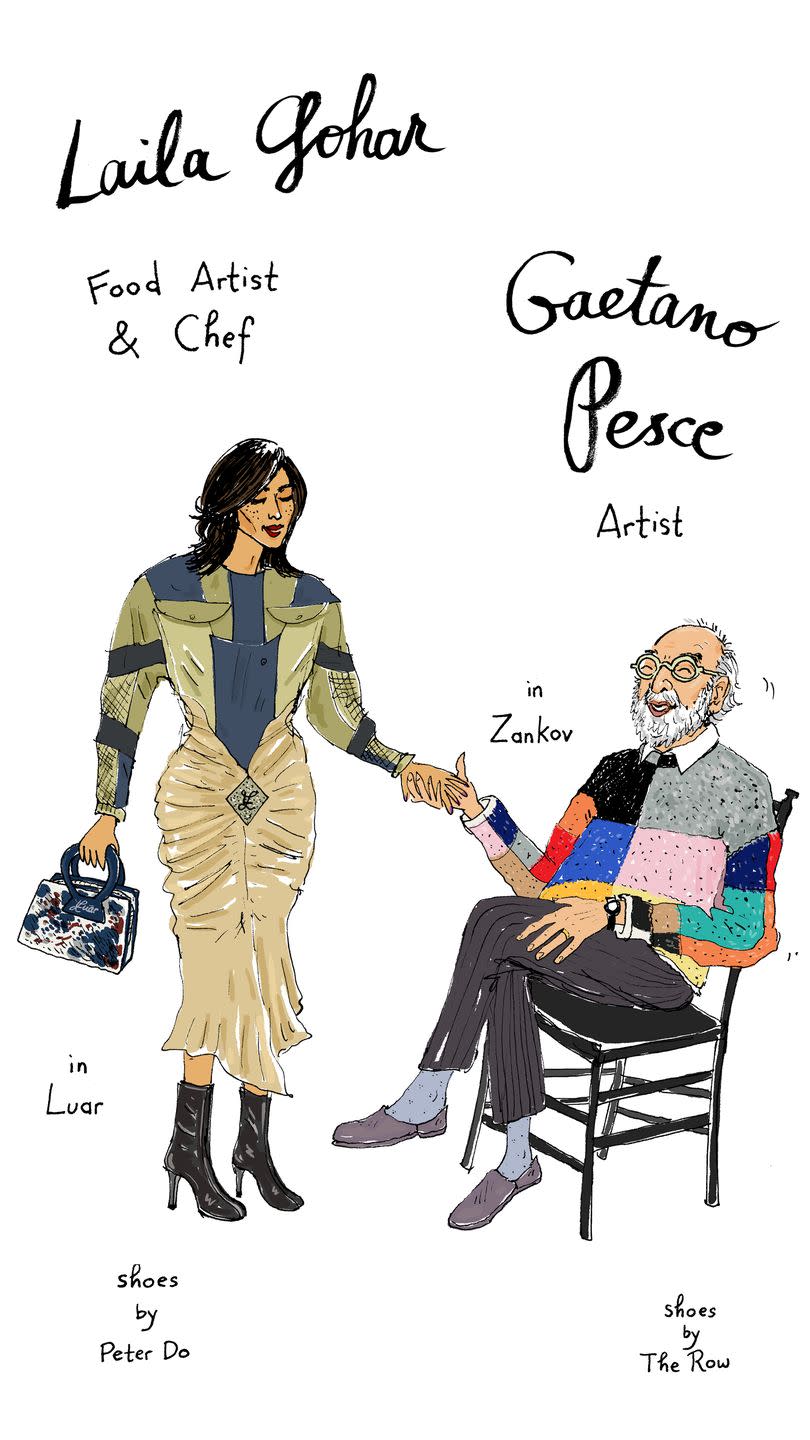

For Spring 2023, Bergdorfs picked up Luar’s clothing in addition to the bags, and even featured his dress in a campaign released this week of beloved New Yorkers wearing the highlights from New York designers’ spring collections in illustrations by Joana Avillez.

“Luar represents the essence of what is so exciting about New York fashion right now,” said Yumi Shin, chief merchandising officer at Bergdorfs. “Every detail of the brand reflects Raul’s distinctively inclusive style. There’s a feeling that Luar is for everyone. It’s a celebration of identity, joy, and the always energetic spirit of Raul himself.” Shin said that while the bag is “youthful,” the boldness of “its materiality and color” make it something “that can be ever-present in your wardrobe.”

In essence, Luar is a powerfully contemporary statement about making it. His clothes are about aspiration, but they are also about resourcefulness, and creating your own sense of belonging through style. Luar, and other brands by Lopez’s peers, like Bode, Telfar, Christopher John Rogers, and Fear of God, suggest that the emerging generation of American designers is rewriting the definition of luxury as something long lasting and extremely personal. They share an aesthetic of beauty and glamour that eschews assimilation. Each is commercially minded, though they’ve found that stability through meaningful products—quilt jackets from Bode, gorgeous tailoring from Fear of God, perfect and collectible dresses by Christopher John Rogers, Telfar and Luar handbags that feel like voting for good designers with your dollars—rather than licensing deals or celebrity-fronted accessories campaigns. Not a single one of these designers is attempting to echo what a European peer or predecessor has done. They have their own version of success. (Still, Lopez said, “I want the European house,” though he’d prefer to revive one rather than succeed another designer.)

Just as important to Lopez, as a fashion history snob, is the fact that his clothes and the bag are things that anyone could look fabulous in: “The bag itself, it’s done its own thing. It’s created its own world, and it’s the world that I want people to belong in.” It’s not just a bag for kids in Bushwick or the art world or who follow certain kinds of fashion accounts on Instagram. He’s seen a woman in a hotel bar carrying a crocodile Birkin in the crook of her arm with his Ana across her shoulder. “She’s universal.”

You Might Also Like