Louisville woman escaped war-torn Haiti as a child. Now she's trying to rescue her sisters

Jazmin Williamson couldn’t see the difference between her and her sisters at first.

When the American teenager traveled back to her homeland in 2017 to visit her biological mother and two younger sisters, the similarities in her face, hair, and skin were undeniable. Even though 13 years had passed since Jazmin left Haiti as an extremely ill 6-year-old, she unmistakably looked like a part of this family.

But the director of the Hope for the Children of Haiti orphanage, who had arranged her adoption in 2004, saw the painful disparity so very clearly.

During that trip, he asked Jazmin, who now lives in Louisville, to look her sisters in the eyes and find it, too.

“You have hope,” she remembers him telling her. “They don't. That's the difference.”

Now six years later, as the terror in Haiti has increased, so has the 25-year-old's concern for her biological family. Earlier this year, U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services launched a humanitarian program that allows nationals from Haiti and three other unstable, war-torn countries to enter the United States “in an orderly way” on a two-year trial basis.

This could be Jazmin’s chance to save her sisters.

Gang violence in Haiti has reached new levels of horror, so much so, that many missions and nonprofits that have offered aid for decades have pulled out of the chaotic country. The United Nations Security Council has reported violence has spread from the country’s capital, Port-au-Prince, through the center of the country, which has meant a surge in killings, kidnappings, mutilations, and rapes. More than 2,700 intentional killings were recorded between October 2022 and June 2023, according to the Associated Press, and more than 200,000 people have been displaced.

With that kind of danger, Jazmin’s sisters — who are 12, 15 and 18 — often haven’t been able to attend school. Even if Jazmin could continue to send money to help pay for their education or expenses, the risk attached with traveling to and from the bank is too high.

There are many cultural and language barriers between the sisters, but somehow genuine fear surpasses all of that.

“Help me, I'm afraid,” her sisters tell her when they do get the rare opportunity to call.

Ever since Jazmin was a little girl, she has dreamed of rescuing her siblings and giving them a safe, comfortable home in the United States.

Today it’s so much more than a dream. It’s a necessity.

“Before, I was scared that they would have a hard life, and I wanted to alleviate their pain and suffering,” Jazmin said. “But now, I'm actually scared for their lives.”

'They have nothing here'

Jazmin’s adoptive mom, Jana Williamson, says this mission to help her family has been on her daughter’s heart since her earliest days in the United States.

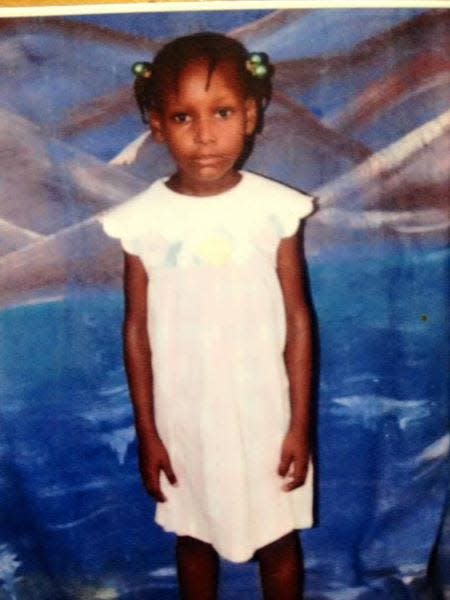

As a young girl, Jazmin and her then 4-year-old sister, Widnie, lived in an orphanage because their parents weren't able to provide for them. They lived in extreme poverty in Haiti, which is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, according to The Council on Foreign Relations. Jazmin still remembers her birth mother explaining to her that she must leave to survive.

“There was fear that my sister and I would die because my mom was unable to feed us,” Jazmin said. “So in the end, it was a really tough decision.”

For the past 19 years, the Williamsons have maintained ties with Jazmin’s Haitian family with the idea that raising the girls is a partnership.

An old family video shows Jazmin at 6 years old rocking a Cabbage Patch doll in one hand and raising the other in prayer. Speaking in her native language, Creole, she asked God to protect her mother in Haiti, and she prayed her family could rescue two of her friends in Haiti from poverty.

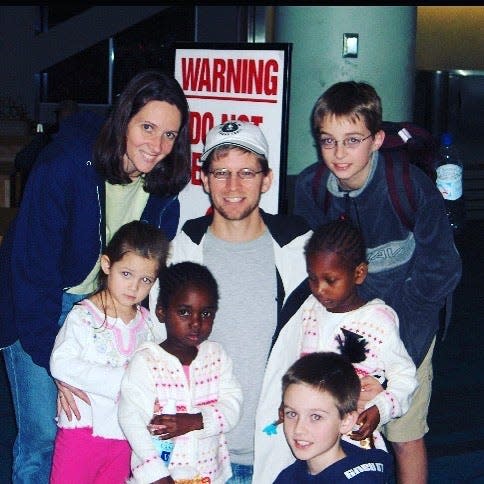

Jazmin’s parents already had two sons and a daughter when they felt called to adopt. When Jana first reached out to the Hope for Children of Haiti orphanage in 2004, the idea was to find a little girl who could be a sister to their daughter.

God’s plan for them was bigger than that.

Jana remembers seeing tanks and military in the streets when she went to Haiti for the first time just before Thanksgiving that year. The day Jana met Jazmin, she was just 26 pounds and her hair had an orangish tint to it, a common sign of extreme malnourishment.

Jazmin locked eyes with Jana.

“Bonjour Manmi,” she said, in Creole.

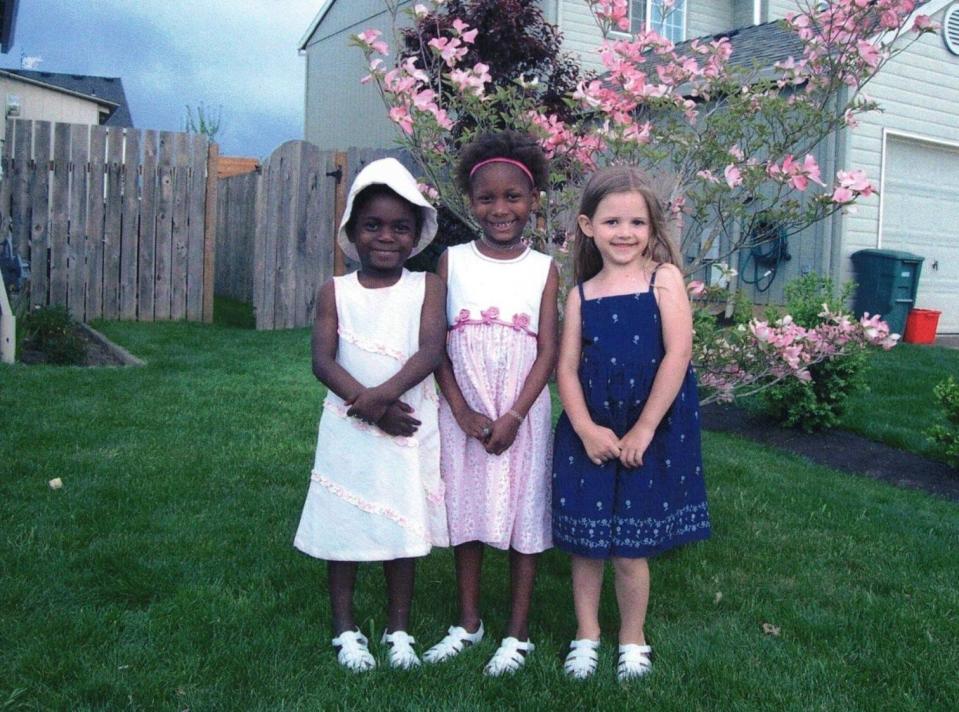

The call to help only grew stronger. In the past 19 years, the Williamsons have welcomed seven adopted children, including the two friends Jazmin prayed for in that old family video.

Jazmin was about 13 the first time she traveled back to Haiti, and really understood just how much danger and destitution she’d left behind.

On that trip, she met with her parents and two younger sisters, who weren’t even born when she left her homeland. She learned they’d lost their house in the devastating earthquake in 2010. They were living under a tarp propped up with sticks.

“What's upsetting you the most?” Jana remembers asking Jazmin as she cried during that trip.

“I complain about going to school,” Jazmin told her mother. “And I complain about things in America, and they have nothing here.”

Most American kids wouldn't have that realization, Jana explained. But Jazmin not only saw it, she wanted to help.

So Jazmin spent her free time raising about $5,000 to build her family a house in Haiti. She spoke to church congregations and sent letters asking people for donations. She was a talented painter for her age, so she made small paintings and sold them for money.

It took about a year, but she eventually paid for the land, materials and labor needed for a house.

“At that time, it was cemented in her that she had to do something to help,” Jana said. “That she had that responsibility.”

Her only chance to help her sisters

Jazmin always assumed she’d be older and more established if she ever welcomed her sisters to the United States. Ideally, she’d already have a solidified career and a home of her own the girls could move into.

A little more than a year has passed since Jazmin finished her master’s degree in global health from the School for International Training Graduate Institute, where she studied in Kenya, India and Jordan. Like many young adults, she’s still finding her footing.

But when President Joe Biden signed an executive order in January that allows Haitians to submit applications to come to the United States for a preapproved, two-year period, under the CHNV program, Jazmin knew it might be her only chance to help her sisters. An opportunity like this might not last forever, and it’s already been challenged in federal court in Texas.

Lisa DeJaco Crutcher, chief executive officer of Catholic Charities of Louisville, says the program allows for 30,000 nationals from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela to travel to the United States each month, but those individuals must have someone in the United States who can support them financially.

Mary Smith, a Louisville woman who serves on the board of Hope for the Children of Haiti, called this program “manna from heaven.” Most Americans don’t realize that Haiti, which sits in the Caribbean Sea, is a two-hour plane ride from Miami or that the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moise in 2021 shattered any sense of democracy.

“Haiti is so difficult ... but yet there are real people over there,” Smith said. “They're dying at rates no one knows about, and they’re being murdered and raped.”

Smith adopted a Haitian daughter after the 2010 earthquake, and now she’s using the CHNV program to sponsor and rescue two of her daughter’s childhood friends who are now in their 20s.

More than 1,200 people have already come to Louisville using this program, and once they’re here, they have a two-year period to advance their status for more permanent residency.

The idea behind CHNV, DeJaco Crutcher said, is to keep people from these war-torn countries from surging the border. Through this process, the Department of Homeland Security can run background checks on the individuals seeking entry, and they can travel here on an airplane. The government can anticipate their arrival and review the financial records of the American connections, like Jazmin and Smith, who have offered to support them.

“Having the ability to issue visas to people who have friends and family members who are willing to support them when they get here, while they're getting on their feet, that's better than just having a crowd of people show up at the border and hoping to make the best decisions," DeJaco Crutcher said.

'You can't help others if you can't help your own family'

Jazmin isn’t naïve. She knows she can't help her sisters alone.

While she doesn’t have the financial stability she once imagined, she does have incredibly supportive adoptive parents. Jazmin is leading this charge, but her mother and father have offered resources and expertise.

Opening their hearts and their family to children from other countries is arguably second nature for the Williamsons, but they’re well aware bringing in an older child and teenagers will be completely different.

The Williamsons have already submitted paperwork for the 18- and 12-year-old, who grew up with Jazmin's Haitian mother. Protocols for CHNV state, specifically, unaccompanied children aren’t allowed in the program, but in this case, the older sister could be the younger one’s legal guardian on paper. Jazmin and her parents would take the lead in raising the 12-year-old once she's here, they said. Eventually, Jazmin wants to help the 15-year-old, too, but Jazmin's parents are separated, and that sister lives with her father. There are more hurdles there.

One of the most difficult parts about the CHNV program for Jazmin is it’s impossible to know when or if her sisters’ applications might be approved. She’s always been a diligent, methodical planner but she can't plan out her life when she's not sure if she's taking responsibility for her younger sisters in six months or six years.

Candidly, Jazmin said the prospect has been daunting and overwhelming. She had dreams of volunteering for the Peace Corps after graduation, but she put that on hold as the death toll in Haiti has climbed. Following that path would mean two years without a paycheck, and she needs money to support them. Jazmin couldn't be overseas while her siblings were here adapting to a new American life.

“This is not a time to question whether or not this is the right thing to do,” Jazmin said. “This is the only thing to do at this point. You can’t help others if you can’t help your own family.”

Initially, it seemed approval from the CHNV program would come quickly, Smith said, but the demand superseded expectations. Five months after the rollout, the U.S. government updated the protocol. Now half of the 30,000 people who are allowed in each month are randomly selected, regardless of their filing date.

The goal, DeJaco Crutcher explained, is to offer a glimmer of hope to people who might otherwise consider crossing the border.

That uncertainty creates plenty of variables for Jazmin.

If her sisters came to the United States sooner rather than later, she’d almost certainly need her American parent's help to raise the 12-year-old. That could mean packing up her life in Louisville and moving closer to her family in Texas. At the same time, Louisville has a rapidly growing Haitian population, and since Jazmin came here in 2022, she’s connected with numerous couples and families from her homeland. That support system could benefit her sisters, too.

If the backlog with the CHNV process pushes her sisters’ arrival back years, that changes everything.

Jazmin would have more time to establish herself, but there’s a dynamic difference between enrolling a middle schooler in classes and helping young adults find jobs.

“I keep telling myself it’s going to work out, but I wish I knew how,” Jazmin said.

'The same opportunity she had'

Watching Jazmin wrestle with this calling creates mixed emotions for her adopted mom.

On one hand, Jana wants her daughter to pursue her dreams and focus on being a 25-year-old. She’s always been an extremely driven young woman, and her mother believes she could achieve anything she puts her mind to. Naturally, her daughter feels an obligation to her biological sisters, but Jana and her husband Shane have been clear with Jazmin: No one is forcing her to sponsor her sisters.

“We let her know that they are not your full responsibility, you don't have to do this,” Jana said. "But she obviously feels the desire to, so we're 100% behind her.”

On the other, she’s incredibly proud of her. When Jana arrived in Haiti just before Thanksgiving in 2004, she was laser-focused on adopting those two sickly little girls and giving them a safe and happy home in the United States.

Now Jana sees that same determination in Jazmin.

“She wants ... her sisters to have that same opportunity that she had,” Jana said.

The Williamsons are actively exploring resources in Louisville and Texas to assist the sisters once they arrive. A couple of months ago, Jazmin began working with trauma victims at Family Health Centers in Louisville, and she's gaining experience on the job that may help her siblings adapt.

In recent weeks, Jazmin has raised enough money to pay to move her sisters from their village into the same compound the Hope for the Children of Haiti children have relocated to because of the violence. Now her sisters are in school, and they’re learning English. They have access to food and medication.

The same orphanage director, who arranged for Jazmin’s adoption, has secured Haitian passports for her sisters.

Really, all that’s left to do is wait.

While it is impossible to know how many days, months, or years may pass before Jazmin can bring her sisters to true safety, so much has already changed since the day six years ago when the director asked her to look into her sister's eyes.

All these years later, they have hope, too.

Reach reporter Maggie Menderski at mmenderski@courier-journal.com.

About Hope for the Children of Haiti

Hope for the Children of Haiti, Inc. is a Christian organization that operates a children's home for more than 85 orphans and vulnerable children in Haiti. Recently the organization was forced out of its home of 26 years due to violence in Port-au-Prince, and relocated to a more secure place away from the city. Roughly 94% of donations to the 501c3 nonprofit go toward the needs of Haitian children. To learn more visit hfchaiti.org.

About Catholic Charities of Louisville

Catholic Charities of Louisville assists people of all races, backgrounds, and beliefs. The organization is a social-service ministry of the Archdiocese of Louisville and serves people in need in its 24 counties in central Kentucky. The organization is actively looking to partner with potential employers. Visit cclou.org to learn more.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville woman hopes to rescue sisters from Haiti under CHNV program