How Long Can Running Keep Alzheimer’s at Bay?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Five common words, arranged in an order I’ve never heard them said before. I nod, a silent “yes, exactly.” And then I give up: “I’m sorry, what?”

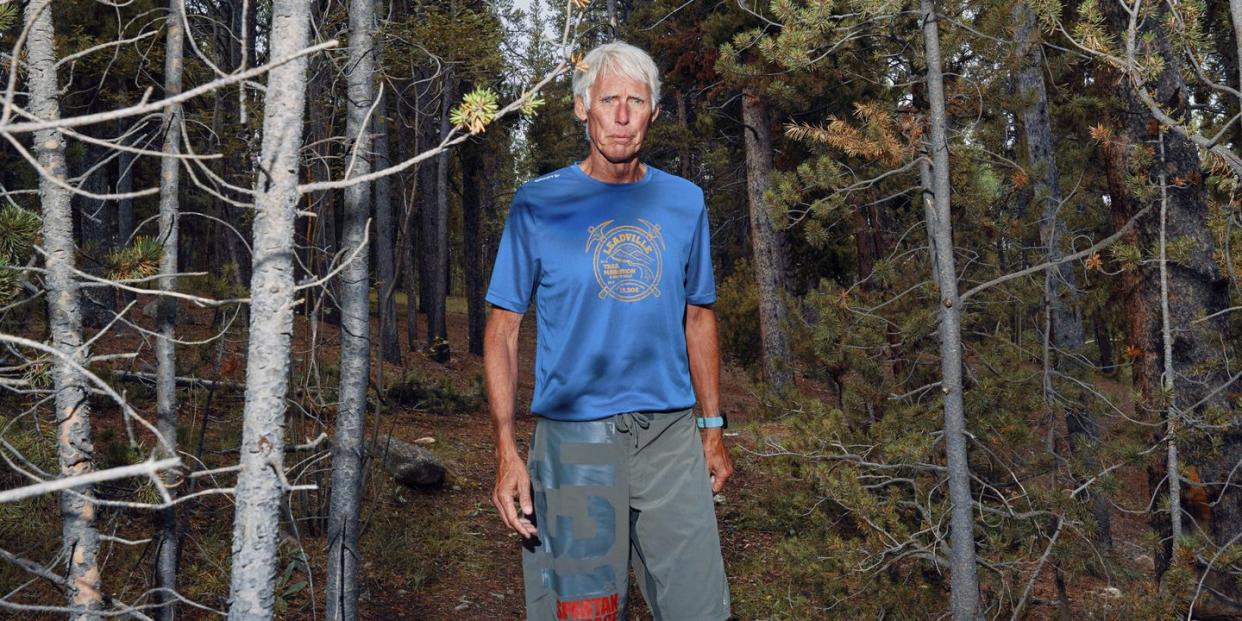

“It never always gets worse” is part of Travis Macy’s answer to my perfectly reasonable question: “How and why would a person run one hundred miles, all in a row?” Hundred-mile races are but one of the many superhuman things he and his father, the equally legendary endurance athlete Mark Macy, 68, have both done multiple times over multiple decades. How—why—does a person take on a race where a 20-hour finish is an aspirational result? I have run marathons before, I have felt the pain and the elation and the thing where a stranger hands you an orange slice and you put it in your mouth. I have pushed myself past my limits. At least I thought I had. But I have never crossed a marathon finish line and thought to myself, Let’s do this roughly three more times right now. How do you mentally get yourself to 30 miles, to 50, to 100? How do you keep going, long after any sensible person would tell you to stop?

“You have to remember that it might actually get better,” Travis, 39, explains. “You tend to think, I feel this bad after 20, I’m going to feel twice as bad after 40, but how do you know? Maybe you won’t.” It is a testament to his general charisma level that I find myself believing him. “If you keep eating and drinking, if you surround yourself with positive energy, you might hit a point where you feel better.” Travis smiles. “Things turn around, that’s what happens in any long-distance event.”

I’m with the Macys, Travis and Mark and their wives Amy and Pam, on a family hike. I’m with them because I want to talk about how a person becomes an ultra-racer, but I’m also here because I want to know how this family is weathering the latest complication in their collective long-distance event: In 2018, Mark Macy was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, an incurable and terminal illness.

“You have ups and downs out there,“ Travis says, “but the lows don’t always just get lower. You can still find some good.”

Mark nods at his son, and then at me. “It’s not that hard,” Mark says. And we keep moving.

We’re in the town of Salida, Colorado, about three hours southwest of Denver. Travis and Amy moved here a few years back; they wanted their kids, Wyatt and Lila, to be able to walk home from school and play unattended in playgrounds. Salida is a town full of outdoorsy types. The main drag is one Gold Rush–era facade after another, now housing yoga studios and art galleries. It’s devoid of national chains, and there appears to be one microbrewery for every eight residents. I have taken to this town immediately. It’s like if a Clif Bar were a place.

The family hike is up Tenderfoot Mountain, the town’s focal point. We’ve stopped for a moment because we are at the perfect spot for a panoramic photo, and also because I can’t breathe. There is no way I’m not slowing this family down, but they’re gracious enough to pretend otherwise. Mark does these kinds of trails regularly, up Evergreen Mountain, near where he and Pam live. He’s usually running them, of course—an hour or two, a 1,000-foot gain, maybe twice a day. Swimming had been part of his daily routine, until the rec center in his town closed for the pandemic. He’ll get back to it. “Of course, because of my Alzheimer’s, I can’t drive anymore, so Pam will have to take me there,” he says, “and that’s a pain in the butt, for me and for her.” I’d been looking for the graceful way to bring it up, the elephant on the side of the mountain. When you meet Mark Macy, you don’t want to bring it up. It feels like introducing the subject of his Alzheimer’s will drag it into the realm of what is real. And when you talk to him, when he fixes his attention on you and those blue eyes hit you like high beams, it doesn’t feel real. He’s too present, too together, even if when you first approached him, Pam was tying his running shoes. He brings it up himself, both to put it out into the open and to diminish its power, as I will learn is his way. He first addresses the subject of Alzheimer’s—a disease that is slowly robbing him of his cognitive function—in terms of being a nuisance.

The Macy family has faced its share of what we will call nuisances, and the breezy way they discuss them often makes you ask them to repeat themselves. Pam has had a liver transplant, and then—because of the long-term effects of the antirejection medication—a kidney transplant, and then another, 15 years apart, one from each of her brothers. She will tell you this like she is telling you what she had for breakfast. In gratitude, Mark donated a kidney to a stranger at age 64. “I had a spare one,” he shrugs. Travis has dealt with nuisances of his own; sometimes he’ll tag a memory with statements like “That’s the time I ripped my spleen in half,” and barrel forward with a story about something else. (I did ask him to back up for this one: snowboarding accident as a teenager. The spleen healed up fine.) I might be the only thing the Macy family will slow down for.

This nuisance is different. Around 2015, Mark began to forget things. Basic words, people’s names. This wasn’t like him. Mark was a full-time attorney with a weekend hobby of traveling the world winning marathons, triathlons, and adventure races. Pam urged him to see a doctor, the doctor urged him to see a neurologist, the neurologist gave them the news: Alzheimer’s. No treatment, no cure, no hope. The “get your affairs in order” speech, the “go for a good vacation while you can” advice, an estimate of two years left. A real pain in the butt, you have to agree.

As of October, that visit to the neurologist was four years ago. Mark kept moving.

“We all have healthy cells inside of our brain that allow us to speak, talk, and think,” says Victoria Pelak, MD, neurologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and one of the many specialists the Macys have consulted since 2018. “They interact with other cells in the cortex that do a lot of automated functions, like keeping our heart rate going, or allowing us to digest.” For all of us, those cells begin to die off in our 40s, but in an Alzheimer’s patient it’s accelerated “10 to 100 times beyond the speed of death of our brain cells in the cortex over time,” she says.

The good news for Mark is that regular exercise can slow down the death of those brain cells. Pelak tells me, “Everything that we know to date shows that the more active you are, the more of a heart-healthy diet you eat—those things contribute to slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease more than any other therapy that we have.” The good news for the rest of us is that we don’t have to do day-long trail runs up a mountain to reap the same benefits. “The brain is an organ just like the heart and eyes,” Pelak says, “and good cardiovascular health fights inflammation and plaque buildup in the blood vessels.” She says even 10 minutes a day of moderate exercise can decrease the progression of disorders that lead to dementia in the future, but the ideal is one hour, four to five times a week. Beyond the general cardiovascular effects, the high-level physical challenges Mark continues to take on keep his brain active. “Activities that are challenging and involve processing, like training for races, where you’re making schedules and setting goals, are all extremely important to maintaining good brain health.”

They also have another benefit, which is that they call upon our brain’s more durable memories. Alzheimer’s robs its sufferers of their day-to-day details: names, dates, directions home. But procedural memories—remembering how to ride a bike or swim in a pool or put one foot in front of the other—tend to hang on longer. Pelak brings up musician Glen Campbell, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2011 and continued touring through 2012. “He was able to play and sing at a very high level, when he was having difficulty remembering what he did three hours before.”

As your memories drop off one by one, continuing to do what you know how to do must feel good. Even if what you know how to do is run 100 miles.

“A lot of young boys look up to their dad as the strongest person on earth,” says Nate Dern, one of Travis’s high school friends, “but I think that’s more true for Travis than anyone else I know.” Travis Macy grew up idolizing his father, which seems like the natural response when your father does superhero shit. Mark was a local legend in their Denver exurb of Evergreen, Colorado, a regular guy who would coach soccer and chaperone church trips and then duck out for a week to run across the Sahara Desert. Travis wanted to follow in Mark’s footsteps, so he did. He ran track and cross country in high school, and he graduated to longer and more grueling races at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Not that he’d tell anyone. He and Amy were on a bus back to UC from a show in Denver when they had their first real conversation. “He wanted to eat my food, which is what Travis does,” Amy says. In conversation, Travis revealed he liked to do races on the weekends. “I said, ‘Well, I did the Avon Breast Cancer three-day 60-mile walk last summer, just so you know who you’re talking to.’ And Travis being the humble dude he is, said, ‘That is so great.’” Travis’s secret identity stayed a secret. “For months, I didn’t know who I was dating. He’d come home and I’d ask how he did, and he’d say, ‘Fine,’ until I finally had to ask what fine meant, and he’d say ‘Oh, I won it.’” She wouldn’t find out until months later that the “it” was often an ultramarathon or an adventure race. Superhero shit, just like his dad. Amy’s telling me this story over pizza at Amicas, a popular place just off the Salida main drag. Mark and Pam are there, with Travis and Wyatt and Lila. The waitress has a quick, private word with Amy because they’re working on her college applications together, because that kind of selflessness and quiet, confident mentorship runs in the Macy family even if you married into it. Eleven-year-old Wyatt asks his mom, “So when did you find out he was good?” Without missing a beat, Mark tells the kid, “Couple of weeks ago.”

Travis has gone on to do marathons, ultramarathons, quadrathlons, adventure races, and plenty more of your unfulfilled New Year’s resolutions. Amy says, “We have been lucky enough to see emergency rooms all over the world.” He still does those long events from time to time. Most recently, he’s taken on burro racing, a uniquely Colorado tradition that involves a racer leading a donkey through a long course, with the donkey carrying a 15-kilogram pack saddle with a miner’s pick, pan, and shovel, a tribute to the early settlers of towns like Salida. More to the point, he’s thinking about buying a donkey, just to make the whole process easier. He’s like this, Amy explains. “He gets a new idea and he goes after it like schoolwork.” He’s recently been officially diagnosed with ADHD, for which he tells me exercise really helps, and which gives Amy hope that he will skip forward to a new idea and that they will not soon be living with a donkey.

What Travis has really thrown himself into is coaching: telling mortals how to prepare for some of the superhuman events he and his dad have taken on, what to eat, when to drink. He’s written a book called The Ultra Mindset about how to program your mind for success, and he talks to fellow athletes about it every week on The Travis Macy Show. He also takes on private coaching clients, and last summer, he began helping his dad. Mark had never had a coach like his son before, because in his early days, nobody did. “If anything like what Travis does existed when I was starting out,” Mark says, “I didn’t know anything about it.” Travis put Mark on a strict race-day diet: a banana at this mile marker, a Pro Bar every hour, plenty of water. “Man, he makes it so easy. He knew to feed me what would benefit me and nothing else. When Travis showed up, everything changed.”

Mark points those high beams at his son. They have a bond that’s still evolving, a list of things they still want to teach one another. Even now.

Pam leans toward Amy. “So, where will you put the donkey?”

Travis knows what to feed Mark to keep him moving, but he also knows how important it is for him to keep moving at all. Moving— running, climbing, swimming, paddling, doing whatever it is you do to get through the jungle in Fiji when the objective of every other living thing is to bite you—is what Mark does. Going forward to the next place, step by step, is where Mark lives. “When I’m moving, everything clicks back in,” he says. Travis agrees with Dr. Pelak, “For anyone dealing with any kind of cognitive decline, physical activity is key. Especially if it’s a thing you’re used to from beforehand, it puts you back in your element, you don’t have to worry about anything but just going.”

When you spend time with Mark Macy, you mostly don’t notice that anything is wrong. He’s sharp and personable. You’ll see Pam buckling his belt here and there and write it off as one of the little things couples do for one another when they’ve been together forever. But once in a while, you’ll see Mark searching for a word, or struggling to find his place in a story he’s telling. The high beams come off you for a moment and search the middle distance, trying to illuminate a room in his mind that’s gone temporarily dark. Sometimes he finds it, sometimes he doesn’t. Always you get the sense that he’d rather just be moving. So it makes sense that a few months after the diagnosis, when Survivor producer Mark Burnett announced he’d be bringing back his legendary and grueling Eco-Challenge, the Macy boys would sign up. The 2019 Eco-Challenge would be an 11-day, nonstop event, in which co-ed teams of four race across Fiji’s jungles, oceans, mountains, rivers, and highlands, and then get yelled at by Bear Grylls. Mark had done the race eight times with his four-person posse, Team Stray Dogs. His old friend and longtime teammate Marshall Ulrich says he was the heart of that crew. “The way he approaches challenges, he’s…infallible, or something like that. He’d approach things with caution, but he also knew when to throw caution to the wind.” Ulrich says Mark had an expression that would calm the rest of the team down. “When things got shitty, Mark would say, ‘It’s just a test.’ Whatever we were facing, we would get through it and it would make us stronger. There was a lot of meaning in just that little phrase.”

The possibility of being a burden to his old team wasn’t a test Mark was willing to take on. The Stray Dogs reluctantly filled Mark’s spot, while Travis decided a race with his father was more valuable than a shot at the podium; he formed a team with Mark and a few younger athletes. “He needed those young studs who could really take care of him,” Ulrich says. “He’s perfectly capable of putting one foot in front of the other, and he’s done so many of these that the paddling or running or trekking is almost automatic.” But it’s the simpler stuff that’s a problem when you’re dealing with Alzheimer’s. “Dressing yourself, making sure you’re feeding yourself, that’s…” Ulrich pauses, collects himself. “…That’s where the young studs came in, and they did a brilliant job.” Facing a good friend’s cognitive decline and finding the good in it. It’s just a test.

The Macys called their new gang Team Endure, and their introduction in the premiere of World’s Toughest Race: Eco-Challenge Fiji on Amazon Prime Video is how a lot of Mark’s acquaintances and fans found out about what he’d been enduring. Nate Dern was one of them. “I might have heard something, but I didn’t fully digest it until I saw the show. He said, ‘I don’t know if you know, but I have Alzheimer’s.’ Very casually, like someone saying ‘I’m colorblind, so I might need help with this menu.’” Alzheimer’s affects everyone differently; Dern recalls his own grandmother getting the diagnosis. “Pretty quickly she didn’t seem like herself. But Mark still seemed like himself, still the same tough guy walking through the jungle in the night.”

Dern recalls the moment long ago when he learned what Mark was made of. “He was chaperoning a church river-rafting trip, and I wanted some packing advice because I figured, who better? So I was like, ‘What sunscreen do you bring,’ and he said, ‘Oh, I don’t wear sunscreen.’ I said, ‘Which sleeping mat do you use,’ and he was like: ‘Yeah, no, I just sleep on the ground.’ I thought, Okay, this guy is tough.”

He laughs. “I’m realizing now that this actually might have been really bad advice.”

Mark and Travis Macy have documented their lives since Mark’s diagnosis, in particular their experience on Eco-Challenge Fiji, in the book One Mile at a Time, on shelves in March of 2023. It may have been out on that Eco-Challenge course that both Macys came to understand the limits of toughness. On the night before the start of the race, as the team tried to get their last good night’s sleep, Mark woke up confused. “We had a room with a view of the pool,” Travis says, “and it had all these umbrellas and lights and a snack bar that looked like the Louvre. Dad thought he’d been abducted.” Mark shrugs, and they share a laugh.

But after seven days, three-quarters through the race, at the base of a canyon in the middle of the night, Mark Macy faced the grim truth. “We had to do a canyoneering event in the dark. I used to be a rock climber; the last time I did that race, I went right up the rope. Took people with me even. But this year, our turn to go up the ropes out of the…the…” he searches, “…the canyon came up after dark. I was going to have to jumar [a method for ascending a rope, complicated even in daylight] and I couldn’t see anything, I couldn’t even begin to come up that…that…and there was nothing those guys could do. I’m not supposed to be doing that kind of stuff. I could kill somebody.” Team Endure withdrew. “We didn’t finish that race, and it’s my fault,” Mark says. “If it hadn’t been for me, they could have just gone on and done good, maybe really good.” I tell him I watched the show, and saw that plenty of other very good teams—Team Stray Dogs included—also didn’t finish. Travis agrees and reassures him, “It’s totally fine, Dad.”

Mark says, “Well, no, it’s not. I don’t do that stuff. Dicking around and not finishing.”

“But we had fun.”

“I agree with you, but still. We did not finish that race because of me. Damn Alzheimer’s.” The high beams dim for the first and only time. Just a bit. And just for a second.

Then he smiles. “So, to make a long story short, we had a great time.”

We’re wrapping up dinner at Amicas, talking about the Leadville Race Series, a summer’s worth of trail runs and bike races at 10,000 feet that I’m starting to consider entering, because if you hang out with the Macys for long enough, these things begin to seem logical. I tell them how surprising it was, when I started doing endurance events in my 30s, to see that the really packed and competitive age groups were the people in their 40s and up. How you don’t see as many people in their teens and 20s taking on triathlons as a hobby, and how quickly that began to make sense. As I got older, I began to understand that my body won’t be able to do everything I want it to forever. I became more aware in middle age that time is not a renewable resource.

Mark shakes his head. “I think time is a renewable resource. If you listen to what anyone says about my condition, I have no chance. At all. But I don’t think Alzheimer’s is going to kill me. I’m not scared of it.” Pam puts a hand on his shoulder. “I think we’re both pretty good at staying in the present, and that’s helpful. It’s impossible to know how things are going to change, but if you stay in the present, you can do an awful lot.”

“I’m going to eat well, and I’m going to stay strong, and I’m going to have a positive attitude, and I’m going to say Fuck it,” says Mark.

There he is. A man who’s pushed himself harder than just about anybody else on the planet, with a wife at his side who’s gotten three extensions on her life via transplants that weren’t possible a few decades ago. His son across the table, carrying and building on his strength and his spirit so that it lives on no matter what happens to his body and mind. A daughter-in-law preparing students for college, and two grandchildren taking it all in, poised to do impossibles of their own.

“That’s it. Something else is going to kill me. Fuck it.”

Alzheimer’s doesn’t get better. At least so far it hasn’t, not for anyone. But it will, for someone, somewhere down the line. Someone’s going to be the first. I wouldn’t bet against Mark Macy.

But whether it’s him or not, what he will do is keep putting one foot in front of the other. He’ll keep pushing his limits. And he’ll keep trusting that it will never always get worse.

You Might Also Like