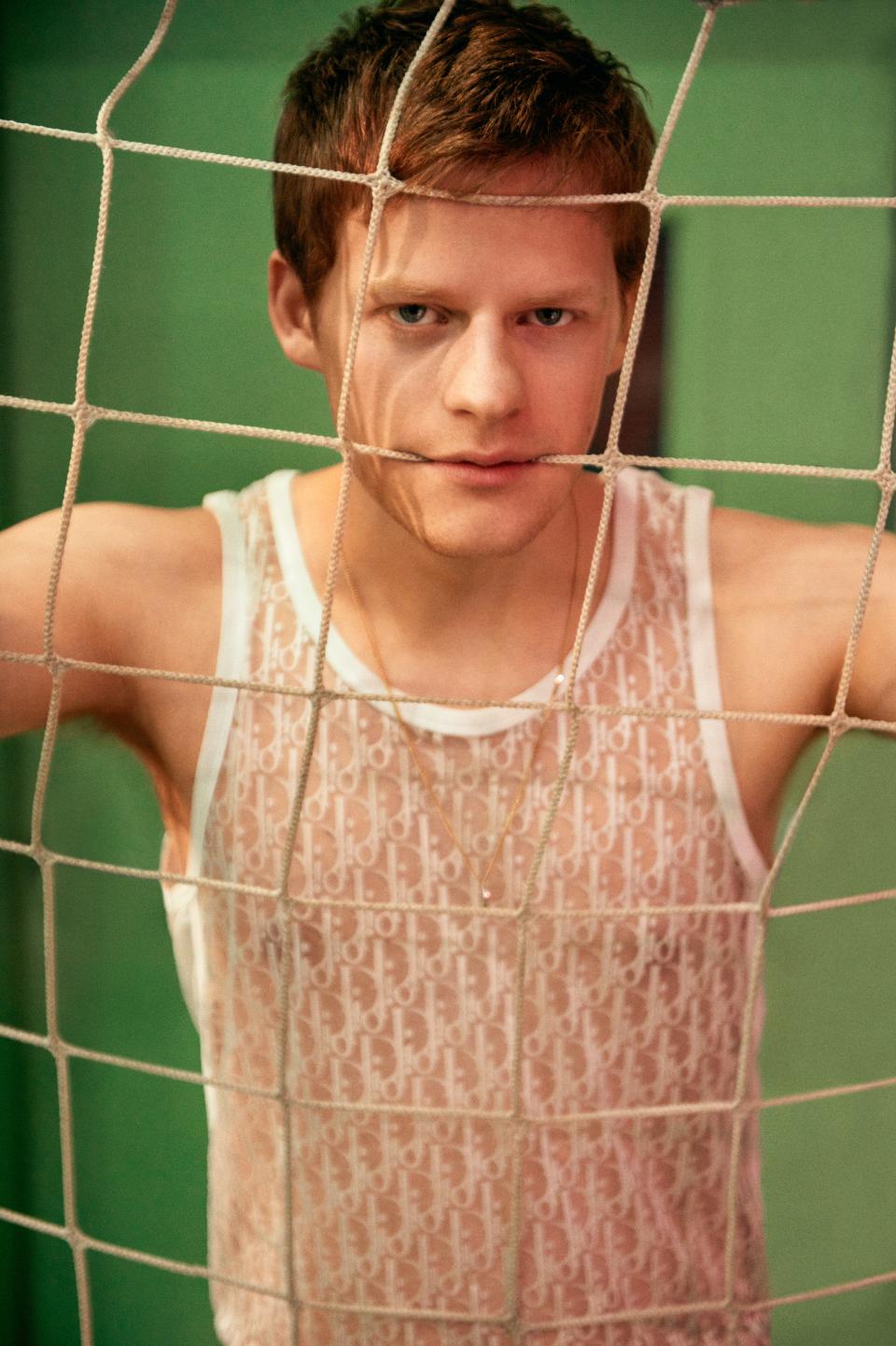

The Long Adolescence of Lucas Hedges

The only thing more “New York” than knowing that the Guggenheim was closed on Thursdays was not knowing that the Guggenheim was closed on Thursdays. Museums are for tourists, not for people who have lived their whole lives here and thus have better things to do with their time, such as watch TV and order crappy Chinese takeout and buy their coffee from authentic, Giuliani-era establishments like Starbucks.

That's what we told ourselves, at least, Lucas Hedges and I, after realizing the doors were locked. The discovery elicited a desperate moment of panic on my part and an Edvard Munch–like fake scream on his. Hedges, who studied acting at an art school in North Carolina for a year but has otherwise spent his entire 22 years in New York, grabbed the straps of his backpack like an earnest alpiner and stared out across Fifth Avenue. Wondering what we would do with the afternoon if not wander around a Frank Lloyd Wright–designed concrete spiral, I asked him, blank-mindedly, the world's worst question: “So how are you?”

We had only met once before, the week prior, for less than two hours, but Hedges seemed to have amplified the initial encounter into something like a deep past, answering with the easy, assumptive intimacy of an old friend.

“I'm gooooood,” he replied. He cocked his head, parrot-style. “I'ma gooooooooooooooooooood.”

We both laughed. It was just the sort of time-embroidering, untranscribable non-joke that Hedges performs constantly, demonstrating, unconsciously, a talent for spotting comic potential in tiny moments that to other people feel like the unremarkable material of mere existence. Like most everything else Hedges would do while we were together, it was very lovable.

Culturally ambitious plans foiled, we headed to Central Park for a walk. It was December but unseasonably warm—“creepy out,” as he put it—and in lieu of a jacket, Hedges wore a crewneck sweatshirt onto which his girlfriend had stitched a bunch of inside jokes in rainbow thread. “I'm so scared of ruining it,” he said. “People keep coming up to me asking, ‘What's your drip?’ ” Showing both common courtesy and admirable theory of mind, Hedges turned to me and said, “Do you know what that means?” I told him I did not. “Your drip is your swag,” he explained. “Are you supposed to provide the brand name of the item?” I asked. “Honestly I don't really know,” he answered. “People have just said it to me. And I know enough to know that it means, basically, ‘What's this thing you're wearing that I think is cool?’ ”

Some of you may not even remember the last movie you saw that didn't have Lucas Hedges in it. He was in Manchester by the Sea, playing a seething, r-dropping, ice-hockey-playing teen, and in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, as a son mourning his murdered sister. He played a gay high school student in Lady Bird and a gay college student in Boy Erased. A drug addict in Ben Is Back. A thuggish, self-loathing burnout in Mid90s. If you happen to live in or frequently visit New York City, you maybe also saw him on Broadway this winter in The Waverly Gallery, Kenneth Lonergan's very funny but also extremely brutal play about a Greenwich Village–dwelling grandmother with Alzheimer's. Hedges, for now at least, is always playing somebody's son—not a kid anymore but still not quite an adult, stronger and taller than whoever is cast as his mom but still inclined to cry on her shoulder.

To many, Hedges is already a celebrity. Soon enough, he'll be one in the cultural imagination of everyone else, too. For the past few years, he's been the secret, under-age heart of everything he's appeared in, but in a year or so, maybe two or three, he'll be everywhere, and seen as an adult. It's fun to watch someone grow up and become famous, simultaneously, in front of the world. It's fun in the way watching a ski jumper take off is fun. The inevitability is thrilling. You know something spectacular is about to happen, no matter how they land it. But you kind of need to hold your breath.

Being a movie star is a totally bizarre job when you think about it, one that fame itself would seem to undermine. Tricking strangers into thinking you're someone else? But then also…doing a bunch of stuff—going on talk shows, appearing on magazine covers—that makes you, the real you, recognizable to the world? It's like the job's chief occupational hazard is also its premise. Hedges likes to mess with this. When people come up to him on the street, which they do more and more these days, it's often with an air of reluctance. “I actually get a lot of ‘You look like this guy, I forget his name. Lucas something?’ ” he told me. “Then I say, ‘Oh, cool.’ And I sort of just…wait. Sometimes they're like, ‘Is it you?’ And, depending on how I feel, I often say no.”

For what it's worth, that's not what I witnessed. Over a few hours I spent with Hedges in downtown Manhattan, about a dozen people recognized him. Roughly half of them gave a quick nod and complimented, in passing, a particular performance. Once, a guy about Hedges's own age stopped dead in his tracks as his friends continued walking.

“Oh my gosh, we were just talking about Lady Bird because there's that scene filmed right there. And I was like, ‘Oh shit, is that Lucas Hedges?’ ”

Hedges grinned. “Cool!” he said.

“What's good, man? Nice to meet you.”

Hedges smiled again. “Yeah, nice to meet you, too.”

“Right on.”

“Well, have a good one.”

“Yeah, you too.”

Hedges turned to me and laughed. “So weird. People just talk to you like they know you,” he said. A few minutes later, a middle-aged woman passed us. She didn't say anything but was walking unnaturally slowly. “God, that woman looked at me like I wasn't even a human being,” Hedges said. “I don't mean like she was in awe of me, more like I was something to be stared at. And I'm not saying this to suggest it's what my life is. I'm not like, ‘Like, see?! People don't even see me as real!’ That's not what I'm trying to say, I swear.”

Hedges, who has titian-blond hair and attenuated limbs, retains that perverse charm of adolescent boys—that heartrending quality that makes you want to kiss them and take care of them at the same time. Hedges is conversationally reactive. He listens attentively. He apologizes when he has to be on his phone for more than five seconds. He's what people mean when they call someone a “good egg.” When we met for the first time, a few hours before he would have to go onstage, he told me he didn't mind that I had a cold. “My mom has one, too,” he offered. He then proceeded to ask me more questions about myself than any employer ever has, than any date ever has, than my parents do after too much time away.

What was my high school like? Do I want kids? Do I consider myself to be maternal? Do I like the experience of being mentored? Is the joy I take in New York City mostly one of nostalgia for a past I never experienced? What does language mean to me? Do I ever read my articles aloud to my mom and dad? How did I meet my husband? What's his name? Would I ever want to write fiction? If we went to a basketball game together, would it actually be useful or would it be too hard for me to hear anything he said? Am I good at giving presents? I wasn't paying for lunch, right? It was on the magazine?

“There’s actually just no way I can be truly great at this until I’ve put in 20 more years.”

—Lucas Hedges

Hedges speaks in ideas-dense sentences built around well-chosen verbs. He worries that his general aversion to texting is “a reflection of some naturally selfish tendencies” and that his affection for movies he knows are dull and not actually any good might indicate “a lack of trust in, or maybe even disdain for, other people.” Hedges thinks film sets are difficult environments in which to experience the pleasures of tutelage because they're so “product-oriented” and that there's something “very dreamlike, almost eerie about being on a theater stage, because even the audience's laughter becomes this alien, dehumanized sound.” He speaks French and Spanish, each pretty well; references, non-annoyingly, both Terrence Malick and the fact that he prefers the company of much older people to that of his peers. Once, while we were eating lunch in SoHo, he got distracted mid-conversation by a man walking by in pajama-like outerwear and fashionable eyeglasses. “Sorry, I was just checking to see if that was Julian Schnabel,” Hedges said, referring to the eccentrically dressed American painter. He looked closer, and it became clearer that the man was possibly homeless. “It's not. It's a poor man's Julian Schnabel. A, er, very poor man's Julian Schnabel.” Hedges would be impressive—curious, canny, cosmopolitan—for a second-semester Ivy League senior with a New Yorker internship secured for the summer. That he's a movie star is insane.

Watch:

Lucas Hedges Tells GQ About His Iconic Roles

To spend any time at all around Hedges is to be convinced that acting is an intellectual pursuit, and that good acting is a cerebral skill. “Most writing is so bad that when something feels real it's actually shocking,” he said. “It's the same with acting—you can tell when an actor is speaking but not also looking at themselves, you know what I mean? Some of the best acting isn't even being witnessed. I've seen friends from college do scenes, and it's honestly better than any acting I've ever seen, and I've worked with the ‘best’ actors in the world.”

Hedges didn't enact the air quotes around “best” until he was halfway through the word, realizing a split micro-second too late that without them he might seem like a dick. But then a split micro-second after that, he recalculated, allowing the air quotes to wilt a bit as he realized having them up there wasn't quite right either. Hedges didn't verbally articulate any of this, but it was obvious that's what was going on inside his head.

“After every movie I do, the only scenes that people compliment me on are the ones where I cry,” Hedges said, laughing. This makes sense. He's a good crier, and crying on command seems really hard. But the thing he's maybe best at—and it's sort of a weird thing to compliment—is portraying barely contained male rage. In Manchester by the Sea, Hedges plays Patrick, a 16-year-old kid outside Boston whose father has just died of heart failure and who is suddenly put in the care of his grieving uncle. The performance got him nominated for an Oscar. Everyone talks about the part where he breaks down, sobbing, after a bunch of frozen meat falls out of the freezer. But that scene is only one minute long; the movie itself is over two hours, and throughout it, in dozens of moments, we see Patrick helplessly enter and then fail to exit concentrated moments of adolescent indignation at a register just barely higher than what would be typical were everything going his way.

“It's not a bleeding heart he's showing you, it's a broken one,” Ashley Gates Jansen, an ordained minister and acting teacher and the person Hedges most credits with “changing his life,” told me. She cited his characters' lack of eye contact and his monosyllabic answers as “the kind of armor that young men put up, that armor of bitterness and cynicism and agitation.” Jansen, who has an 18-year-old son, told me, “I really do see my own kid up there whenever Lucas is on-screen.”

“Any conversation you begin with Lucas, you’re immediately in it. You talk with him and you get the impression that you have the full benefit of his soul turned on you.”

—Kenneth Lonergan

Most of the characters that Hedges has played are, like him, sensitive, thoughtful, smart. Ian, Hedges's character in Mid90s, Jonah Hill's directorial debut about a gaggle of Clinton-era skaters, is, at first glance, an exception. He's self-hating and violent; he steals, beats up his little brother, scowls all the time. Hill wrote the part specifically for Hedges after Hill's sister, Beanie Feldstein, called him from the set of Lady Bird and said, “There's this actor. You're going to freak out.”

To prepare for the role, Hedges spent a few weeks walking around Venice Beach in his costume: head shaved, Eminem-style; diamond studs in his ears; baggy jeans. “It was really shocking how differently people treated me,” he recalled. “People would ask, ‘Did you see the game last night?’ And nobody has ever in my life, not once, asked me if I've ‘seen the game.’ ” Having a shaved head, he said, seemed to inspire fear in people. “If I looked at a girl, she would look away immediately,” he said. “And it was honestly the same with guys.… I've never been a person anyone was scared of, so I think I was a little excited about the prospect of people being frightened by me.”

Hill, who thinks of Hedges “like a little brother,” said that “nobody else could have played that role,” one for which he didn't want to cast someone “who would present as stock asshole.” Hedges, he said, “is a heart with arms and legs” who knows, intuitively, that it's when a person feels most sensitive that they “overcompensate by being harsh and violent.” The very best actors, Hill continued, could also be the very best psychiatrists. “It's the same thing,” he said. “They're interested in human behavior; they're curious about why people do the things they do.” Like Shia LaBeouf, who called Hedges a “truth-seeking missile,” Hill praised Hedges's inquisitiveness, his “billions” of good questions. “When you mix curiosity and sensitivity, you have a great artist,” he said. “When you add incredibly good looks to that, you have a movie star. A movie star who is also a great artist. That's Lucas.” Hill went on to talk about how the roles that Hedges has chosen have allowed him to be seen—by audiences and film critics and all-purpose fans—for who he is. “It took me years and years to figure out a way for my work to align with who I am,” Hill said. “And Lucas is just, well, he's already there.”

After lunch one afternoon in December, we settled into a bench in Washington Square Park, a Manhattan locale best known for the fashionably dressed N.Y.U. students who ramble through it and the murmuring pot pushers who service them. A man with a bongo drum scored our conversation; teenage skateboarders provided the figurative B-roll. “I always wanted to skate, but I could never figure it out,” Hedges said. “They're the coolest people in the world…like how they seem effortless and lazy while also just being really good at something. That's so appealing—doing the most but looking like you're doing the least.” He was speaking in a meandering, only half-conscious way, not realizing that he was, in effect, describing acting and arguably also the reason for his own success. “Were you into skaters?” Hedges asked. But as I was midway through admitting that yes, of course, who wasn't, he interrupted to apologize for the question, which presupposed (correctly) that I didn't skate myself.

In only a few hours, Hedges would be due at the theater where, for four consecutive months this winter, he did eight performances per week of Kenneth Lonergan's The Waverly Gallery. “It's hard to do a long run of a play without having your performance calcify,” Lonergan, who directed Hedges in Manchester by the Sea as well, told me. “It's the same story, the same marks, but the characters have to develop, the relationships have to get deeper and not just fall into a routine.” Hedges, Lonergan continued, “has only ever done one other Broadway play, but there he is, every night, up there with Elaine May and Joan Allen.” The character he plays is supposed to be a few years older than Hedges is in real life. When they began rehearsals, Lonergan explained, that was evident to a degree, but in the few months since, “he seems like he's matured three to four years.”

“Listen, Lucas is not going to have three movies and a Broadway play every year—it’s just not going to happen. But he can wake up every day and try to do meaningful work.”

—Peter Hedges

“I think a lot of people mistake naturalism for relaxation,” Lonergan went on. “But being comfortable is not the same thing as being alive and real and truthful. Any conversation you begin with Lucas, you're immediately in it. He can be a little self-conscious, but he's also very much an open book, and that combination is great in anyone, but it's particularly great in an actor. You talk with him and you get the impression that you have the full benefit of his soul turned on you.”

Hedges's nights usually went something like this: Arrive, eat dinner, stretch, do a bunch of breathing exercises, curtain. But some nights it was more like: Arrive, “fuck around,” curtain. By “fuck around” he mostly meant run absurdist baby names by Elaine May, the play's 86-year-old star. “The one she likes a lot right now that I also love is Oates,” Hedges said. “But I like to mess with her, too. I'm like, ‘What do you think about the name Rope?’ And she goes, ‘Eh, too literal.…’ She likes consonants, and a lot of the names I come up with are more about the vowels. Like Ingemar. I ran that one by her the other night.”

Just then, a man in a black suit and payot approached our bench. “Are you Jewish?” he asked Hedges, pointedly ignoring me. Hedges shook his head. “No, man, I'm not.” The man scurried away. “That was the most suspicious ‘Are you Jewish?’ I've ever gotten in my entire life,” Hedges said, laughing. “Like, was that dude actually just a drug dealer maybe?” We watched him approach a pair of skateboarders who, upon spotting him, immediately rode off. “I can't say those are the two coolest skaters I've ever seen,” Hedges said. “Or…the most Jewish skaters.”

A brief mention of his girlfriend segued into a moment of spontaneous gratitude. “I really can't tell you how amazing life is right now,” Hedges said. “I feel like every interview I do, it's like, ‘I'm so anxious, I'm so scared,’ but I'm just fed up with saying that. I mean, it's true to some extent, but I'm so just so happy right now. Everything's going really well.” He wondered aloud if loving and grieving weren't actually symbiotic emotional states and whether an effective method for keeping a long-term relationship vividly alive might be to try to remember, always, that one's partner would, like everyone else, die eventually. “I know how weird that sounds,” he said, laughing again. It didn't sound weird at all. The only thing weird about it was the uncanny experience of receiving poignant, precocious, and ultimately correct relationship advice, unbidden, from a 22-year-old.

When Hedges is preparing for a role, which, these days, he seems usually to be, he writes himself a letter before going to bed. “Dear Inner Self,” he begins. “If it is your will, please reveal to me in a dream tonight, what it is you'd like me to learn about this character.” Then he dreams whatever he dreams, wakes up, transcribes the images and sensations, and e-mails his dream coach, who responds, therapist-like, with a bunch of questions that in aggregate are meant to produce, for Hedges, what he calls “a blueprint of what all the moments in the movie remind me of in my own life.”

Hedges, who describes his job as the work of “turning the character into me,” knows exactly what he sounds like when he talks about his process. “You know, that's where it sort of becomes very esoteric. To some extent, it's just like, uh, ‘Just act, just fucking act. Act with the other person in your scene.…’ But I don't really know how to suddenly have, like, a whole family history with someone I've known for a week or less.”

Hedges's own family history has been one of privilege: Brooklyn Heights brownstone, private school, intact family, celebrated father (the writer and director Peter Hedges). But it's a nexus of luck that seems to have furnished him with everything the most optimistic and least cynical economists model for: gratitude, generosity, social grace, cultural savvy, intergenerational friendships, confidence. Hedges thinks that if he weren't an actor, he might have liked to be a teacher. It's easy to imagine him leaving a modest, tastefully decorated outer-borough apartment, NPR mug in hand, and taking the subway to some high school in the Bronx.

Growing up under the roof of a director meant early exposure to moviemaking and its adjacent thrills. Hedges appeared as an extra, at the age of 10, in Dan in Real Life, which his father wrote and directed. His first proper role was in Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom, for which he was cast on the spot in the audition, which itself was an indirect result of a seventh-grade production of Nicholas Nickleby. Peter Hedges, recalling the performance, said that “everyone else was in a school play, and Lucas was in a Bergman film.” During intermission, Peter remembers, he asked a group of high school students loitering in the doorway why they were there. “It was an assignment,” they answered ensemble. “Why,” Peter asked, “were high school students assigned to see a middle-school play?” They laughed. “We weren't assigned to see the play—we were assigned to see Lucas.”

A decade later, at the “imploring” of Julia Roberts, Peter Hedges was able to persuade his reluctant son to star in Ben Is Back. Over tea at a Brooklyn coffee shop around the corner from where Lucas grew up, Peter told me, with a bit of remorse, how much he overshot many of the scenes in the film. “It wasn't until we got into dailies and could project it big and I wasn't in a parka, freezing and worried for time, that I was often able to really see his performance. I was repeatedly, I wouldn't say stunned, but in awe at how much was there, how much more there was.”

Peter spoke of his son both as a father and as a professional peer, and by the end of our conversation there were tears in his eyes. “Listen,” he said, “Lucas is not going to have three movies and a Broadway play every year—it's just not going to happen. But what can happen is that you can wake up every day and try to do meaningful work and to also engage meaningfully with family and friends and even the people you meet on the street.” He sighed and knocked three times on the table.

About a month after our first, thwarted attempt, we returned to the Guggenheim, or as Lucas began referring to it in text messages, between pictures of his family dog in a hat, “The Goog.” The current show, a retrospective of the Swedish painter and mystic Hilma af Klint, had, over the few months since it opened, gone from critically acclaimed curiosity to go-to Instagram backdrop. For every two or three severe-looking Appreciators of Fine Art milling around, there was at least one teenage girl done up in a Kylie Jenner Lip Kit.

“Right now I’m not looking to do a project that carries the weight of life itself on its shoulders.… I want to do something that feels very personally significant.”

—Lucas Hedges

Hedges arrived in sweatpants, sleepy-eyed, wearing white Air Force 1s and a Brave New World T-shirt, both well-worn. As usual, he had been onstage the night before and not returned to the SoHo apartment that he shares with his elder brother, who works in finance, until after midnight. “I read about sports at night,” he admitted. “For hours and hours. Like, last night I came home, and I was exhausted, but I couldn't not read about sports. I was on NBA.com, on NFL.com, reading about the Jets, reading about the new head coach, checking the players' Instagrams.” He shook his head and rubbed his eyes.

Before he wanted to be an actor, Hedges wanted to be a basketball player. As a kid, he made everyone call him Sprewell, as in Latrell Sprewell, the small forward who played for the Knicks from 1998 to 2003—i.e., from when Hedges was 2 until he was 7. His bedroom was plastered with posters of basketball players and coaches, to whom he'd pray every night before games. “I was just like, ‘This is what a basketball player should have!’ ” he recalled. “So fucking ridiculous.” Hedges has come to a more realistic assessment of his own talents over the years, though he's still a fan. He sat courtside at Madison Square Garden for the first time a few weeks before we met, but he admitted that he spent most of the game thinking about that episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm where Larry David accidentally trips Shaquille O'Neal.

We made our way up The Goog's iconic spiral ramps, Hedges stopping often to close-read the wall text. His reactions to the paintings were immediate and playful and appreciative and mostly muttered under his breath rather than to me: “Whoa,” “Wow,” “Holy shit,” “This is insane,” “Wait, this is her work, too? Oh, no, ha, that's a Seurat.”

I mentioned to him that I had talked, the day before, with Ashley Gates Jansen, his former acting teacher, and that she had praised the social responsibility with which he seemed to have chosen all his roles to date. He knew what she was referring to. She was referring to him playing characters who are grieving and questioning their sexuality and struggling with drug addictions, but that isn't necessarily what he's most interested in doing going forward, at least not immediately, he said. “I want to do something where you couldn't watch it and say that's wrong or that's bad. I mean, I suppose anything could be bad, but more like something in which it's like, ‘Oh, there are infinite possibilities here instead of aiming for one thing,’ if that makes sense.” He mentioned Wild at Heart, David Lynch's 1990 crime comedy, as an example.

“All I know right now is that I'm really loving getting to do these jobs and that I'm getting a better and better sense of what it is I want to do, and right now I'm not looking to do a project that carries the weight of life itself on its shoulders or even anything super socially relevant,” he said. “I want to do something that feels very personally significant, which might mean something that's actually really insignificant.… I mean, I love dancing, and I was thinking about this on my way over here, how I'd love to just make a music video. Go off somewhere and make one with some friends—or not, maybe just me.”

It's unclear whether other people, having gotten used to the ethical approach he's so far given to his career, will want something as “insignificant” as what Hedges is fantasizing about. Casey Affleck, who co-starred with Hedges in Manchester by the Sea and whom Lonergan witnessed being a mentor to Hedges on set, said, “He's kind of a shining example of the best of his generation. He's socially conscious, he's informed, he's confident but humble and kind, too. He's really expressive and supportive and earnest and won't be deterred despite his humility. He makes me think of those kids in Parkland, you know? I mean, they're all just so amazing, and it makes you think, Jesus, everyone over 25 should just get out of the way for all the Lucases of the world.”

Hedges resisted talking about his career as anything methodical or planned, as a possible plot that he himself had intentions about or even the ability to control. “Anything that exists in a collective consciousness, it probably doesn't actually exist,” he said. By collective consciousness, Hedges means consensus, a sometimes tacit, sometimes blurted-from-the-headlines agreement among moviegoers and critics and fans about who he is and what he's up to: “Like, if it goes down in the historical narrative, it's somehow less trustworthy to me, because it's like once something gets believed by a mass number of people, you have to wonder if it's actually true. The people whose opinions I care about most exist outside of this collective consciousness, so there's a part of me that really doesn't trust this big old narrative about whatever is happening with me, because it's like, well, if I asked the people I respect most, they might be like, ‘Eh, I didn't really like that movie, to be honest.’ ”

I asked for an example of someone whose opinion he trusts.

“My friend Fred,” he answered.

“Careers don't exist,” he continued. “Does a father or a mother exist in any way other than how they are with their children? A parent who would think in terms of a bigger picture is to some extent completely absent to their children.… A father who is making decisions to be This Kind of Father? To me that doesn't even seem like a father.”

Hedges paused, suddenly aware that whatever he just said could possibly sound, to my ears, pretentious or abstract or maybe even stoned. “Yeah,” he said. “Yeahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh.” And then he laughed.

Tourists with Nikons yoked around their necks passed us by; so did art students, children, and pearly-haired women in interesting eyewear. By the time we reached the second floor, Hedges had begun to modulate his speech in a way I hadn't heard before. Sometimes, midsentence, he would lower his voice to a near whisper. There was never a pause, never an interruption in what was an otherwise fluent and charming conversation, and it didn't immediately occur to me that he wasn't just speaking and listening but also clocking everyone around us, adjusting his voice, in real time, to strangers' various levels of voyeurism. It was like being with an intelligence agent.

“So much of it is luck,” Hedges said. “And I feel like there is some force watching over me that's making it really fucking easy for me. And I don't mean like it's so easy for me to do great work, but for whatever reason my path has not so far looked like the path of someone who has been working for 40 years and not gotten a job. It just hasn't. And I guess because it hasn't looked like that, I'm really wary and cautious of accepting praise in any way because there's actually just no way I can be truly great at this until I've put in 20 more years, there's just no fucking way. And I think a lot of the actors who get success at a really young age, they're just not as good. How could they be?”

We had reached the top of the spiral by this point. Hedges peered over a rail and onto the terrazzo lobby six coils down. “Are you afraid of heights?” he asked. “I'm terrified of them.”

Alice Gregory is a GQ correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the March 2019 issue with the title "The Long Adolescence of Lucas Hedges."

Watch: