Logan Lerman Doesn’t Want to Wear the Tights

Logan Lerman talks about his career in black and white terms. The handful of projects he’s carefully chosen since his teenage Perks of Being a Wallflower fame either worked or they didn't.

Hunters is one that works—and Lerman is far more responsible for the ambitious show’s success than a cursory glance at his IMDb credits would suggest. In fact, Hunters creator David Weil calls Lerman “the beating heart of the production. He’s tireless—working early mornings and late nights every day and then doing it again the next day and the next day. He’s of course a brilliant actor, but he’s also an expert producer and filmmaker in his own right, and his notes and ideas for scenes are so well-rounded, so thought-provoking. We had an immensely collaborative set, and Logan helped create that.”

The series follows a patchwork team of 1970s Nazi hunters, led by Holocaust survivor turned New York power player Meyer Offerman (Al Pacino), who have made it their personal mission to pinpoint the locations of war criminals who fled to the U.S. Joining Offerman in his pursuits are the Markowitzs (Carol Kane and Saul Rubinek), weapons specialists; Sister Harriet, a former MI-6 agent turned nun; Joe Mizushima, a Vietnam vet who handles the bloodier work; Lonny Flash (Josh Radnor), a washed-up Hollywood C-lister; and Roxy Jones, a no-nonsense badass. They’re essentially the Justice League but with murkier moral compasses and fewer skin-tight bodysuits.

No one pulls the show’s disparate, unwieldy threads together more tightly than 28-year-old Lerman. Playing Jonah Heidelbaum, a 19-year-old Brooklynite who witnesses his safta’s brutal murder one night, Lerman is Hunters’ emotional and ethical core, an actor tasked with both grappling with the show’s central questions and also serving as a vessel through which the audience can start to unpack those very same concerns.

Hunters is a gamble in every sense of the word. Though the series is executive produced by someone who knows a thing or two about horrifying his audiences, Jordan Peele, Hunters—like Peele’s films do—often tonally flip flops, from more somber, respectful storytelling to pulpy interludes and blood-splattered Nazi skull-bashing.

But there’s no clean way to tell a story of this magnitude—not that Lerman is interested in neat or tidy at this stage in his career. He's learned that neat and tidy often come hand in hand with compromise. And after more than two decades in Hollywood, Logan Lerman is done compromising.

When Lerman was first approached to play Jonah, he was given only one script, for the pilot (“it needed a lot of work,” he says). Committing to the possibility of multiple seasons of work—this is his first TV show since he starred on the then WB’s Jack and Bobby from 2004-2005—almost scared him out of accepting. “The idea of blindly committing to a project without knowing the material is not something I would ever do,” the actor says.

Because on paper, Hunters solves like history’s simplest arithmetic problem—Amazon financing a series produced by Jordan Peele, starring Al Pacino and a Hollywood’s murderers row of a supporting cast, about Nazi Hunters. But when Lerman signed on, there no Pacino yet. Lerman was, for a moment, The Name. But beyond his initial hesitancy to commit, he knew in his gut the show would be worth the risk, because it “sounded really fucking cool,” he says. “I wanted to see that show. I was curious about it. I figured that out early on.”

“Jonah sets off on an odyssey of epic proportions, transforming from an ordinary, drug-dealing, comic-book-loving teen into a heroic Nazi-hunting vigilante exploring the morality of revenge and justice,” Weil says. “I needed an actor who could truthfully capture the depths and degrees of such a character. Enter Logan. He’s a young man, but he has this magnificently old soul. The character is a high wire act, and Logan pulls it off seamlessly.”

Some execs might’ve bristled at the thought of ceding even a shred of creative control to their actors. But Lerman says it’s the very nature of Hunters’ shooting schedule and all-hands-on-deck environment that empowered him, with Pacino’s vocal on-set support, to flag concerns before they ballooned. Scripts changed daily. Things like choreography for a weed-induced Coney Island dance sequence were taught moments before cameras rolled. “We never finished an episode on time so we ended up just shooting four or five episodes in the same week,” he says. “It's insane. It was crazy.”

“There are a lot of episodes in this season where I read them and I was like, ‘Oh my god, what the fuck is this? We need to reshape this,’” he says, choosing his words carefully. This desire to make his work better, he’s quick to note, is something he learned to fight for after years of compromising. “It could have been a battle with everyone creatively,” he says. “It could have even been litigious, because I would never do things I don't feel comfortable doing. Fortunately, people [like David] were supportive and thought I made the show better. That kind of creative environment that supports artists is not common in television. But something where you're blindly committing to episodes that you haven't read... that's where you have to put your foot down and say, ‘This is me and this is something I don't feel comfortable with.’”

Lerman was born in Beverly Hills in 1992, and was raised in a Jewish household, the son of an orthotist (his father) and a Hollywood manager (his mother). He started working young, acting in films like The Patriot (2000), Riding in Cars With Boys (2001), and The Butterfly Effect (2004). On the surface, a lot of that early onscreen work feels incongruous with the more sharply defined trajectory he’s taken in the past decade. There’s the Percy Jackson & the Olympians franchise, a two-movie series he anchored that are based on popular YA books about Greek mythology. There’s 2011’s critically savaged The Three Musketeers in which he played D'Artagnan, a promising gig that failed to help him achieve career liftoff.

It took until 2012’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower for the actor to majorly hit Hollywood’s radar. Before then was a time in his life that taught Lerman not only what he wanted, but also exactly what he didn’t. “I made a lot of mistakes,” he says. “I did a lot of things that didn't make me feel good. I compromised a lot when I was a kid. I learned a lot. I found that I'm guided by what makes me feel best at the end of the day, so I'm picky now. I'm pickier.”

For a while, he lost track of who he was, after falling into the trap of taking roles for the sake of having work, or in the hopes they’d take his career out of neutral: “Sometimes you get taken off-course. Hollywood culture is really gross and superficial. I found myself being productized and manipulated by the Hollywood machine, but then I'd find myself getting back to who I am, and liking that form of representation, and learning from it.”

It’s been seven years since Lerman’s last franchise film, and eight years since Perks. Lerman knows the spotlight’s been off him for a while. He feels the sands of time accumulating at the bottom of the hourglass. That’s part of the reason, he says, Hunters felt right, right now. It’s not for attention or fame (he talks often throughout our time together about how disinterested in either he is). But “you can only make independent films for so long without losing your ‘value’ in the industry,” he says. “If I don't take projects that have wider releases and more money behind them, then my value to help an independent film get made diminishes and I'm not able to make films anymore.”

Because Hollywood is, at its core, a math equation. One wrong calculation and it can all go kaput. “No one's going to want to finance a movie with me years down the line if I don't have films that people are seeing,” he says. “I made a few independent films recently that have managed to find audiences, but it doesn't exactly help my ‘value.’ For years, I've just read shit that I didn't want to do.”

Lately, Lerman’s decided to refocus his energy on passion projects—ones less visible, maybe, but more fulfilling, he says. Since 2014, he’s appeared in movies like David Ayer’s WWII drama Fury and an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel Indignation, both of which were liked by critics if not embraced widely by audiences. Hunters, he says, served as the perfect next step for two reasons. It’s a show he believes in. And it gives him room, he hopes, to pursue the smaller, more thoughtful movies he’s grown to love.

“I've had bigger projects that I've turned down,” he says. “I look back and I'm like, ’Oh, that was successful. It wasn't something that I really liked, but I probably should have done that.’ But this one came around and I was like: ‘I'm right for it. And I like it.’”

He’s not too concerned with stability and comfort, at least at the moment. “I'm pretty low key,” he says. “I'm not selling clothes. I'm not really engaged on social media. It's interesting to pick and choose the moments where you really want to work, where you really want to be seen. But I'm just an actor, first and foremost. I just want to disappear.”

That’s where his past comes back into play. Part of the problem for Lerman’s present stems from the shell he built up over years of compromising just for the sake of a gig, or a check, or a shot of adrenaline in his career’s metaphorical thigh. “Now, studios aren’t making movies that aren't based off of IP that matters to them,” he says. “If you try to get in there, you get stuck in the bureaucracy trying to get approval from the chains of command. Then you're going nowhere.”

“Plus,” he adds with a knowing smirk, “I don't really want to wear tights and shit.”

While Lerman is certainly thoughtful about his own choices, he’s less inclined to ascribe necessity to any project he puts out. Hunters is the type of show that feels totally of this moment, a series that uses the horrific events of the past to speak to the horrific underpinnings of our current administration, and the resurgence of bigotry and hatred our sitting president has actively encouraged since taking office. It’s not preachy, but it’s entertainment that actually has something to say. But “I don't know if we need this show, or if we need any shows,” Lerman says. “I don't put that much importance on any of the stuff that we do."

Hunters is by no means a surefire hit yet. All ten episodes dropped in late February, and though people were definitely watching, some of the initial critical reception skewed rough. “Hunters’ part-pulp sensibility frequently veers into hamminess – and that’s on top of the discomfort arising from taking this approach to a historical trauma the size, weight and fathomless depth of the Holocaust,” Lucy Mangan wrote in The Guardian. “After seeing five episodes, I'm still struggling to decide if the show is quality TV, and if I like it or not,” wrote The Hollywood Reporter’s Daniel Fienberg. “What I'm sure of is that I find it fascinating.”

Two days after the show’s release, the Auschwitz Museum spoke out on the “dangerous foolishness and caricature” of the show. “Auschwitz was full of horrible pain & suffering documented in the accounts of survivors,” the museum stated on its official Twitter account, referencing a pivotal, horrific scene in an early episode. “Inventing a fake game of human chess for @huntersonprime is not only dangerous foolishness & caricature. It also welcomes future deniers. We honor the victims by preserving factual accuracy.”

Weil issued a lengthy response to Deadline later that night, pointing out that he acknowledged the horror and violence of the Nazi reign and “simply did not want to depict those specific, real acts of trauma.”

“It is not documentary. And it was never purported to be,” he added. “In creating this series it was most important for me to consider what I believe to be the ultimate question and challenge of telling a story about the Holocaust: how do I do so without borrowing from a real person’s specific life or experience?”

Weeks before the controversy, Lerman—whose paternal grandfather, Max, fled the Holocaust, from Berlin to Shanghai—spoke to the very core of the back-and-forth as he tried to sum up why the show felt if not necessary, then at least timely. “If there's ever a reason why we need art like this out there, it's that it's distinctly anti-fascist, and that's important to program into the minds of anybody who watches it,” he says, growing more animated as he talks. “There's no, ‘Nazis are the good guys too,’ in this show. They're bad. It doesn't play with that: it's distinctly anti-fascist and anti-Nazi. Maybe that's important in an election year. Maybe it's important in a world where there's a rise in interest in fascism. Maybe that combats the public sentiment.”

Lerman, who was Bar Mitzvahed at Los Angeles’ Temple Beth Am, has said that he’s now an atheist who doesn’t belong to a temple. But there’s still something about the way Hunters wrestles with faith and justice that resonates with him. It’s what drew Weil to him in the first place. “Part of my desire to create this show was to realize a character I myself had rarely, if ever, seen on screen: a Jewish superhero,” the creator tells me. “A Jewish character with strength and might and agency and power and a hint of bad-assery—and for a brilliant Jewish actor like Logan to bring that character to life was deeply important.”

As Lerman politely mentions multiple times during our conversation, he hates doing press. He’s been burned before. He’s done photo shoots where stylists have coerced him into wearing clothing he’d never even think about putting on. He’s had his words twisted. He’s been forced to compromise. But for Hunters, a project he’s passionate about, he’s happy to put himself through the wringer again. If it means more people find the show, he says, it’ll all have been worth his time.

“Hopefully 10 years down the line, I can look back at this interview, look back on the decade, and say, ‘I got a lot of things done,” he adds. “Something like Hunters is one of those special opportunities that stood out and made me want to just be an actor again for a minute.”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

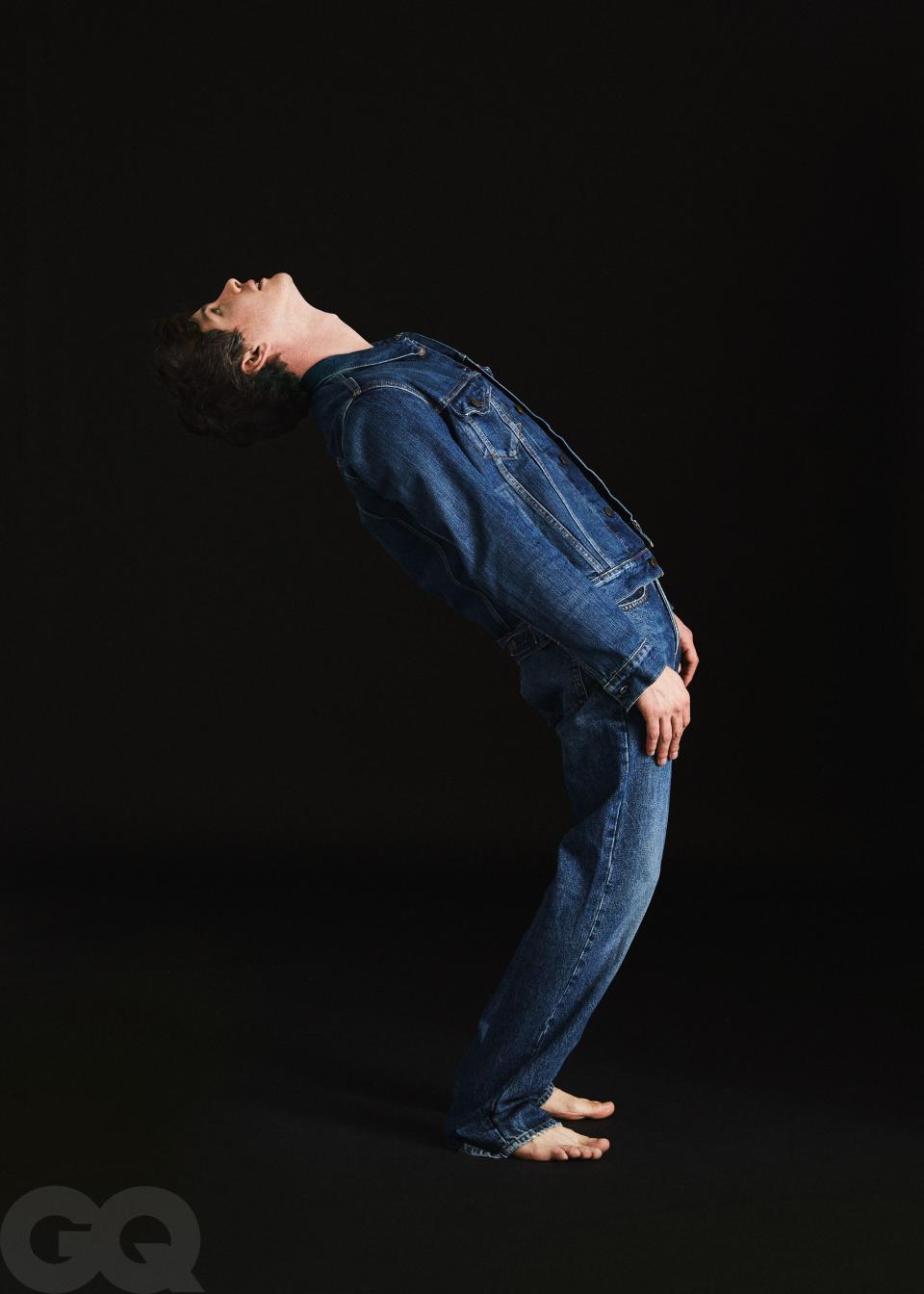

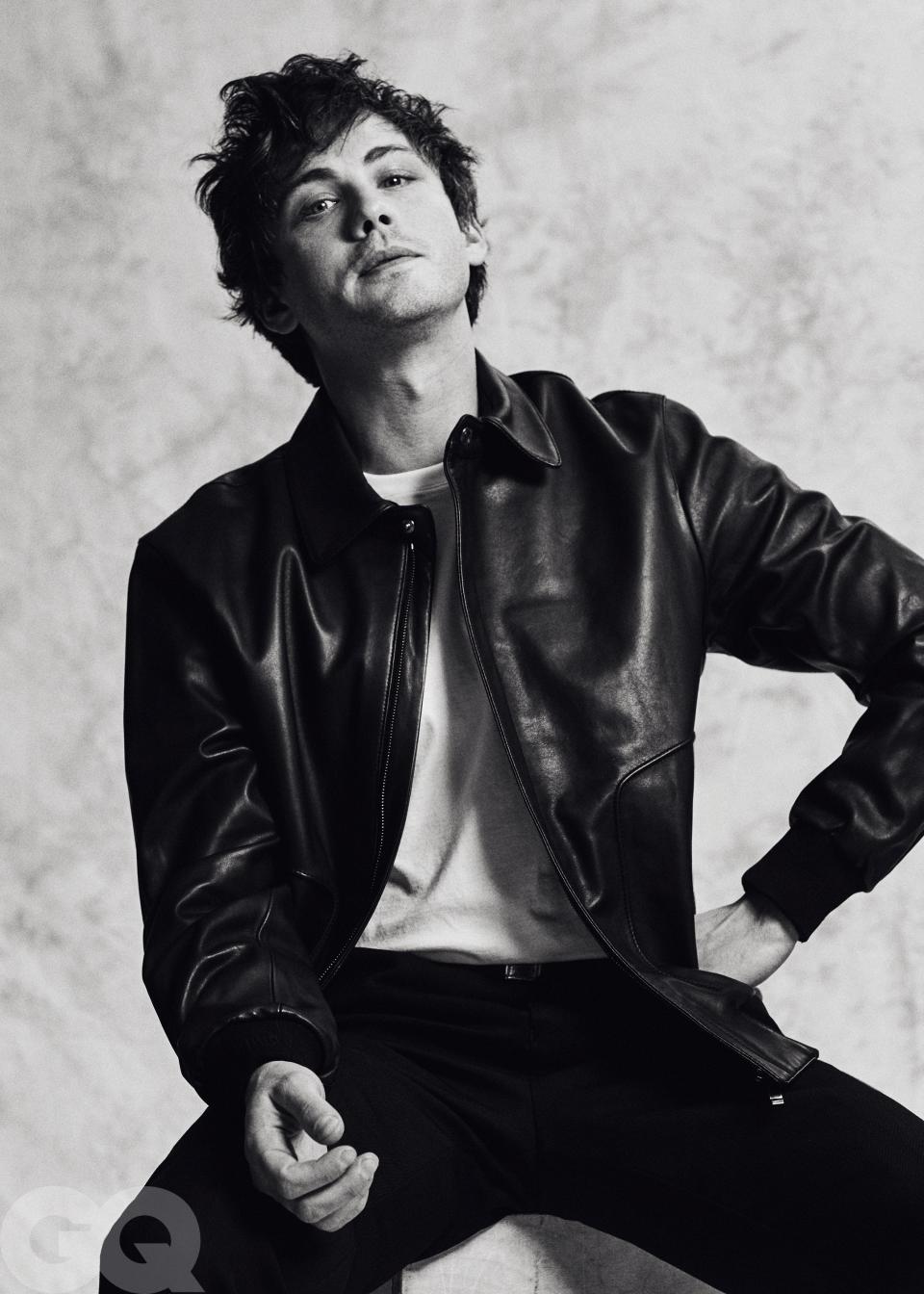

Photographs by Matt Martin

Styled by Taryn Bensky

Grooming by Janice Kinjo

Originally Appeared on GQ